Sexual Self-Concept Differentiation: An Exploratory Analysis of Online and Offline Self-Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

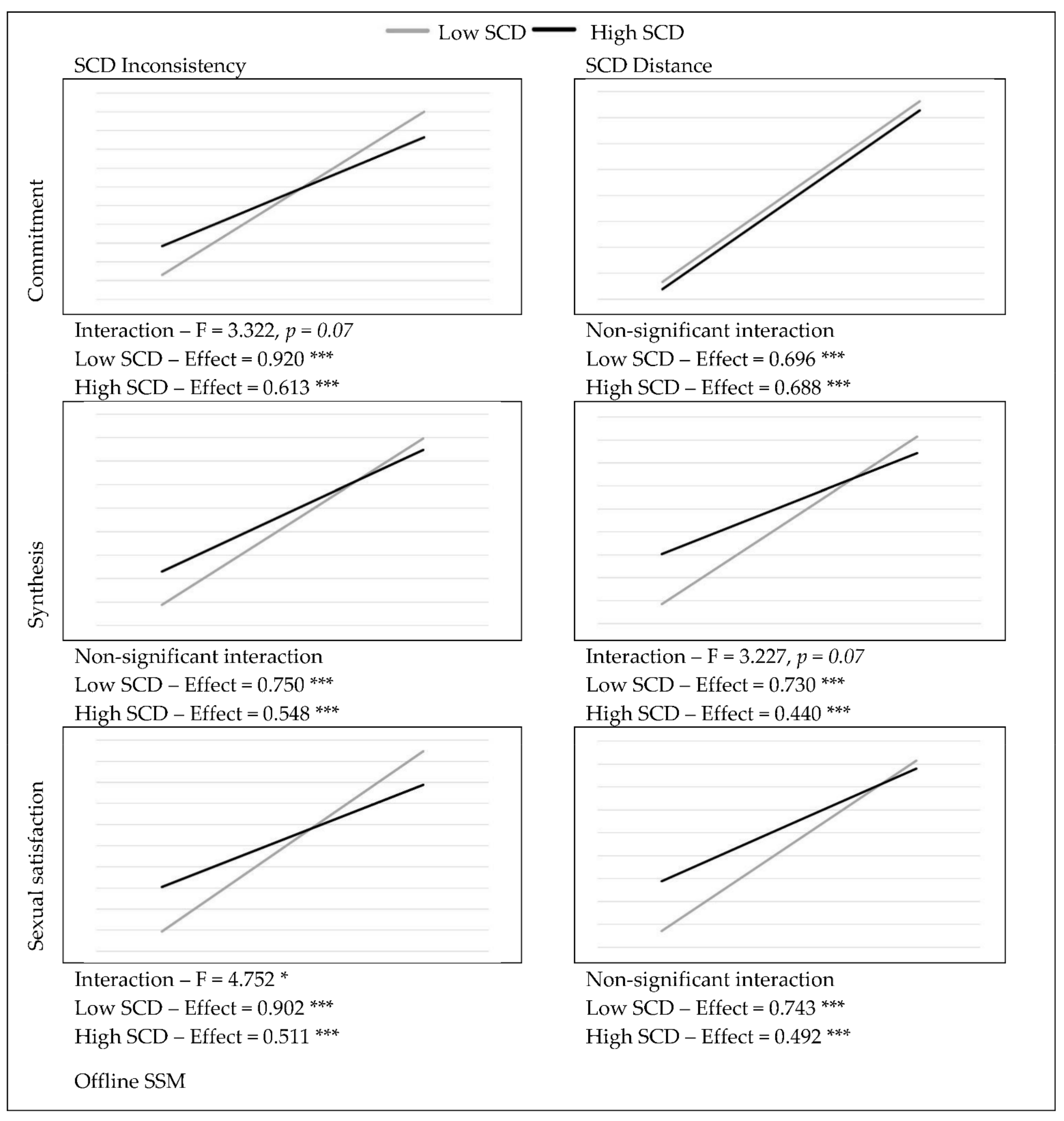

3.2. SCD Moderation Analysis

3.3. Analysis of Variance

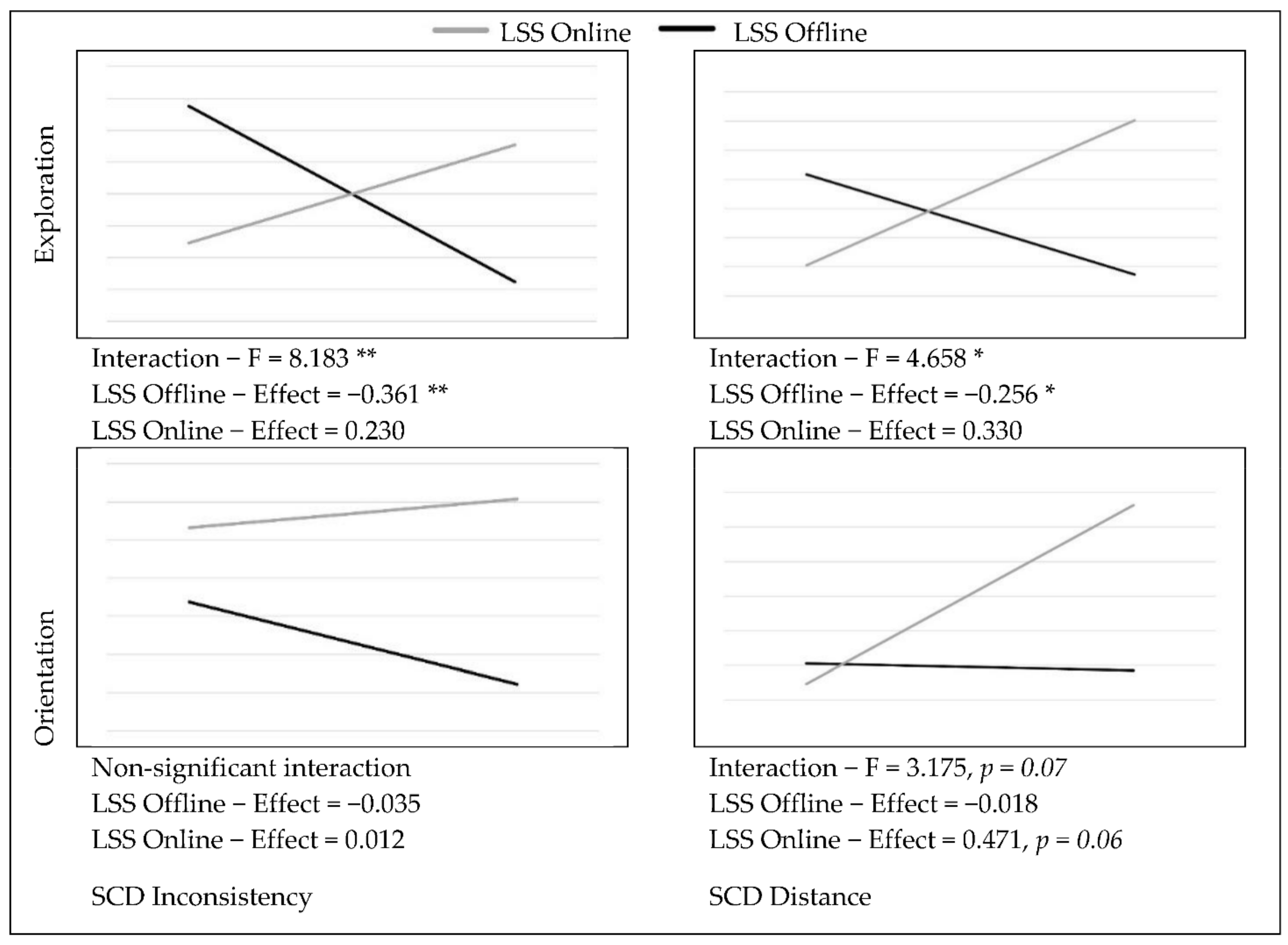

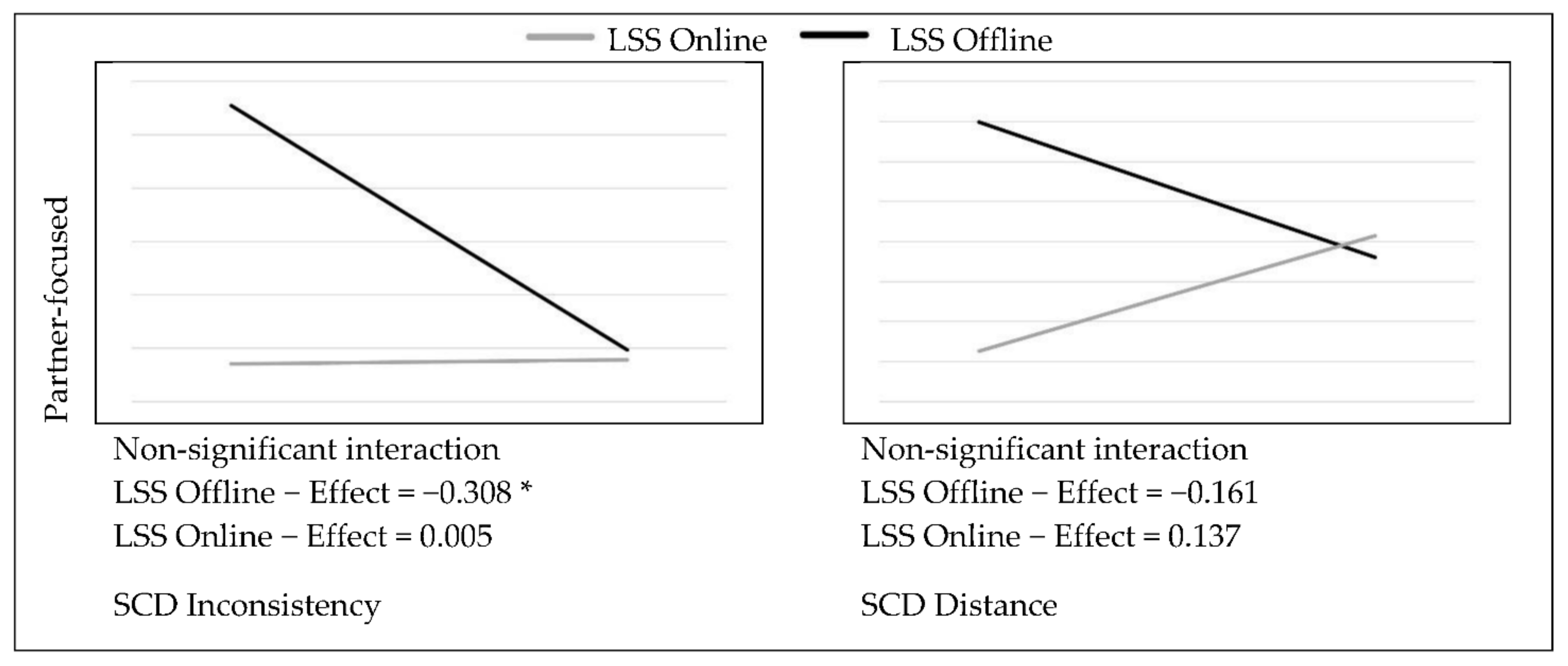

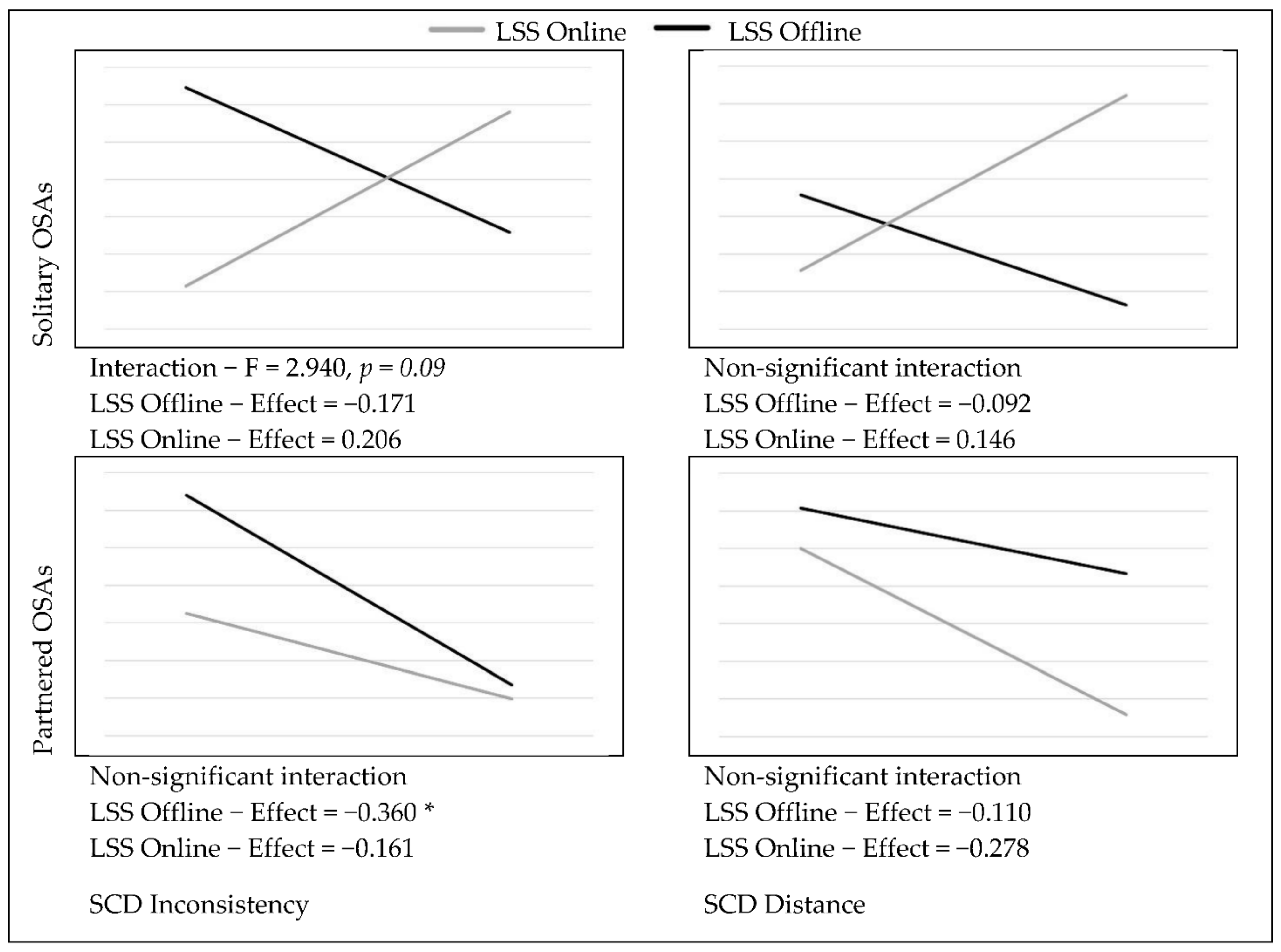

3.4. LSS Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barak, A.; Fisher, W.A.; Belfry, S.; Lashambe, D.R. Sex, Guys, and Cyberspace: Effects of internet pornography and individual differences on men’s attitudes toward women. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 1999, 11, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents’ Exposure to Sexually Explicit Internet Material and Notions of Women as Sex Objects: Assessing Causality and Underlying Processes. J. Commun. 2009, 59, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J. Internet Pornography Exposure and Women’s Attitude towards Extramarital Sex: An Exploratory Study. Commun. Stud. 2013, 64, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, S.R.; Coulson, G.; Keddington, K.; Fincham, F. The Influence of Pornography on Sexual Scripts and Hooking up among Emerging Adults in College. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 44, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boies, S.C.; Knudson, G.; Young, J. The Internet, Sex, and Youths: Implications for Sexual Development. Sex. Addict. Compulsivity 2004, 11, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. Internet sex addiction: A review of empirical research. Addict. Res. Theory 2011, 20, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.; Hodgins, D.C. Examining Correlates of Problematic Internet Pornography Use among University Students. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Morahan-Martin, J.; Mathy, R.M.; Maheu, M. Toward an Increased Understanding of User Demographics in Online Sexual Activities. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2002, 28, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, K.; Byers, E.S.; Clowater, S.L.; Kalinowski, A. Self-Appraisals of Arousal-Oriented Online Sexual Activities in University and Community Samples. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 43, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, K.Y.A.; Bargh, J.A. Coming out in the age of the Internet: Identity “demarginalization” through virtual group participation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, K.Y.A.; Green, A.S.; Gleason, M.E.J. Relationship Formation on the Internet: What’s the Big Attraction? J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J.A.; McKenna, K.Y.A.; Fitzsimons, G.M. Can You See the Real Me? Activation and Expression of the “True Self” on the Internet. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, K.; Greenfield, P.M.; Tynes, B. Constructing sexuality and identity in an online teen chat room. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 25, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; McLoughlin, I.P.; Campbell, K.M. Sexuality in Cyberspace: Update for the 21st Century. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2000, 3, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvalem, I.L.; Træen, B.; Lewin, B.; Štulhofer, A. Self-perceived effects of Internet pornography use, genital appearance satisfaction, and sexual self-esteem among young Scandinavian adults. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grov, C.; Gillespie, B.J.; Royce, T.; Lever, J. Perceived Consequences of Casual Online Sexual Activities on Heterosexual Relationships: A U.S. Online Survey. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 40, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donahue, E.M.; Robins, R.W.; Roberts, B.W.; John, O.P. The divided self: Concurrent and longitudinal effects of psychological adjustment and social roles on self-concept differentiation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlstrom, J.F.; Cantor, N. Mental Representations of the self. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 17, pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauman, T.J.; Higgins, E.T. Self-Discrepancies as Predictors of Vulnerability to Distinct Syndromes of Chronic Emotional Distress. J. Pers. 1988, 56, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M. Attachment style and the mental representation of the self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 1203–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, M.; Neimeyer, G.; Brown, E. The Divided Self Revisited: Effects of Self-Concept Clarity and Self-Concept Differentiation on Psychological Adjustment. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 20, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Hastings, C.T.; Stanton, J.M. Self-concept differentiation across the adult life span. Psychol. Aging 2001, 16, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, A. Effects of self-concept differentiation on sense of identity: The divided self revisited again. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 48, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Assanand, S.; Di Paula, A. The Structure of the Self-Concept and Its Relation to Psychological Adjustment. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linville, P.W. Self-Complexity and Affective Extremity: Don’t Put All of Your Eggs in One Cognitive Basket. Soc. Cogn. 1985, 3, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.J.; Ross, S.R. Elaboration Versus Fragmentation: Distinguishing between Self-Complexity and Self-Concept Differentiation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 22, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateizer, A.; Avram, E. Mobile Dating Applications and the Sexual Self: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, A.L. The Meaning of My Sexual Self. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures; Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 533–534. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, R.L.; Savoy, H.B.; Navarro, R. The Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MoSIEC). In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures; Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 434–437. [Google Scholar]

- Stulhofer, A.; Buško, V.; Brouillard, P. The New Sexual Satisfaction Scale and its short form. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures; Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 530–532. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J. Ego identity, role variability, and adjustment. J. Consult. Psychol. 1961, 25, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Hay, E.L. Self-concept differentiation and self-concept clarity across adulthood: Associations with age and psychological well-being. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2011, 73, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, W.L.; Walker, L.J.; Wiens, T.K. What Do We Know When We Know a Person Across Contexts? Examining Self-Concept Differentiation at the Three Levels of Personality. J. Pers. 2012, 81, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Timm, T.M.; Keiley, M.K. The Effects of Differentiation of Self, Adult Attachment, and Sexual Communication on Sexual and Marital Satisfaction: A Path Analysis. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2011, 37, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.; Narciso, I.; Novo, R.; Pereira, C.R. Predicting couple satisfaction: The role of differentiation of self, sexual desire and intimacy in heterosexual individuals. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2014, 29, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferreira, L.; Fraenkel, P.; Narciso, I.; Novo, R. Is Committed Desire Intentional? A Qualitative Exploration of Sexual Desire and Differentiation of Self in Couples. Fam. Process 2014, 54, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, A.; Schweitzer, R.; O’Brien, J. Correlates of Female Sexual Functioning: Adult Attachment and Differentiation of Self. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, K.Y.A.; Green, A.S.; Smith, P. Demarginalizing the sexual self. J. Sex Res. 2001, 38, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, A.D.; Offman, A. The interrelationships between sexual self-esteem, sexual assertiveness and sexual satisfaction. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2009, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Antičević, V.; Jokić-Begić, N.; Britvić, D. Sexual self-concept, sexual satisfaction, and attachment among single and coupled individuals. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.M.; Amarelo-Pires, I.; Biscaia, M.S.P.; Machado, P.P.P. Sexual self-esteem, sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction in Portuguese heterosexual university students. Psychol. Sex. 2018, 9, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, C.E. The relationship between Internet use and self-concept clarity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauhoff, S. Self-Report Bias in Estimating Cross-Sectional and Treatment Effects. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 5798–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SCDI | — | |||||||||||

| 2. SCDD | 0.593 *** | — | ||||||||||

| 3. Online SS | −0.373 *** | −0.677 *** | — | |||||||||

| 4. Offline SS | −0.133 | −0.186 | 0.577 *** | — | ||||||||

| 5. SOSAs | −0.037 | −0.043 | −0.074 | −0.197 * | — | |||||||

| 6. POSAs | −0.239 * | −0.114 | 0.066 | 0.092 | 0.389 *** | — | ||||||

| 7. ESSx | −0.007 | 0.04 | 0.422 *** | 0.613 *** | 0.032 | 0.103 | — | |||||

| 8. PSSx | −0.153 | −0.101 | 0.428 *** | 0.498 *** | −0.066 | 0.051 | 0.769 *** | — | ||||

| 9. Exploration | −0.169 | −0.186 | 0.380 *** | 0.230 * | 0.202 * | 0.232 * | 0.393 *** | 0.410 *** | — | |||

| 10. Commitment | −0.112 | −0.161 | 0.459 *** | 0.698 *** | −0.102 | 0.14 | 0.624 *** | 0.495 *** | 0.208 * | — | ||

| 11. Synthesis | −0.052 | −0.056 | 0.434 *** | 0.551 *** | −0.058 | 0.178 | 0.523 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.355 *** | 0.695 *** | — | |

| 12. Orientation | 0.016 | 0.069 | −0.322 *** | −0.548 *** | 0.235 * | 0.051 | −0.374 *** | −0.269 *** | 0.117 | −0.66 *** | −0.453 *** | — |

| Mean | 0.608 | 0.625 | 91.028 | 97.292 | 6.792 | 3.057 | 24.915 | 22.934 | 35.094 | 29.198 | 24.198 | 5.642 |

| SD | 0.312 | 0.637 | 20.924 | 17.511 | 3.029 | 3.569 | 4.737 | 5.949 | 9.254 | 5.848 | 4.701 | 3.594 |

| LSS Offline | LSS Online | F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 63 | n = 32 | ||

| Solitary OSAs | 6.71 (3.07) | 7.00 (3.15) | 0.180 |

| Partnered OSAs | 3.30 (3.67) | 2.46 (3.17) | 1.193 |

| Commitment to a sexual identity | 29.76 (5.69) | 27.28 (6.11) | 3.829 * |

| Interest in sexual exploration | 34.41 (9.59) | 35.43 (9.39) | 0.246 |

| Sexual-orientation uncertainty | 5.39 (3.62) | 6.46 (3.79) | 1.801 |

| Sexual-identity synthesis | 24.00 (4.81) | 23.75 (4.48) | 0.060 |

| Ego-focused sexual satisfaction | 25.50 (4.18) | 23.50 (5.69) | 3.808 * |

| Partner-focused sexual satisfaction | 23.38 (5.81) | 21.81 (6.50) | 1.426 |

| Online sexual self | 87.38 (22.56) | 93.62 (17.11) | 1.893 |

| Offline sexual self | 101.84 (14.71) | 85.90 (18.36) | 20.983 *** |

| SCD inconsistency | 0.65 (0.28) | 0.61 (0.32) | 0.266 |

| SCD distance | 0.75 (0.71) | 0.56 (0.45) | 1.964 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mateizer, A.; Roșca, A.C.; Avram, E. Sexual Self-Concept Differentiation: An Exploratory Analysis of Online and Offline Self-Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126979

Mateizer A, Roșca AC, Avram E. Sexual Self-Concept Differentiation: An Exploratory Analysis of Online and Offline Self-Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):6979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126979

Chicago/Turabian StyleMateizer, Alexandru, Andra Cătălina Roșca, and Eugen Avram. 2022. "Sexual Self-Concept Differentiation: An Exploratory Analysis of Online and Offline Self-Perspectives" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 6979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126979

APA StyleMateizer, A., Roșca, A. C., & Avram, E. (2022). Sexual Self-Concept Differentiation: An Exploratory Analysis of Online and Offline Self-Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 6979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126979