Abstract

Systematic reviews have demonstrated the scarcity of well-designed evaluations investigating outdoor nature-based play and learning provision for children in the early learning and childcare (ELC) sector among global Western countries. This study will examine the feasibility and acceptability of the programme and the evaluation design of outdoor nature-based play and learning provision across urban ELC settings in a Scottish metropolitan city. Six ELC settings with different outdoor nature-based play delivery models will be recruited. One trial design will be tested: a quasi-experimental comparison of children attending three different models of outdoor play and learning provision. Measures will be assessed at baseline and five weeks later. Key feasibility questions include: recruitment and retention of ELC settings and children; suitability of statistical matching based on propensity score; completeness of outcome measures. Process evaluation will assess the acceptability of trial design methods and provision of outdoor nature-based play among ELC educators. These questions will be assessed against pre-defined progression criteria. This feasibility study will inform a powered effectiveness evaluation and support policy making and service delivery in the Scottish ELC sector.

1. Introduction

The early learning and childcare (ELC) environment is an important setting to support healthy child development. Providing outdoor nature-based play and learning in the early years (0 to 5 years) setting can encourage children to be physically active and develop their social and cognitive skills, while helping them maintain a healthy weight later in life and support more equitable access to local green spaces [1]. However, there is a growing concern that the increasing availability of tablets, smart phones, and television watching, along with a high number of risk averse parents, is culminating in children who are less physically active, who are spending a lot of time indoors, and who have interrupted sleep patterns [2,3,4]. By providing children with more time outdoors in rich green spaces, nature-based ELC could be a key approach for supporting children’s physical, social, and emotional development.

The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend that preschool-aged children (3–4 years) should spend at least 3 h per day physically active, including 1 h in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) [5]. However, research suggests that preschool-aged children struggle to meet the recommendations for MVPA and spend most of their time in low physical activity (PA) [6,7]. MVPA is associated with positive mental health, cardiorespiratory fitness, and body mass index (BMI) in adolescence, therefore it is important to promote these healthy behaviours in the early years [8,9]. Being outdoors is a positive correlate for PA in children [10]. Furthermore, PA, especially outdoor play, is positively associated with most sleep outcomes in preschool-aged children [11]. The natural outdoor environment has a variety of affordances that have the potential to support children’s development of their motor competence, social skills, mental wellbeing, and physical health [10,12,13,14]. A recent review of the literature found positive associations for sedentary time and balance (a key component of motor competence) among children attending nature-based ELC [15]. However, the authors concluded that more high-quality research is required that better describes the nature exposure and outcome measurement tools [15].

Providing children with opportunities to spend time outdoors engaging in unstructured play, especially in nature, is a potentially effective approach for supporting emotional and social resilience and cognitive and physical development [16,17,18]. Through play outdoors, children can engage in a variety of play behaviours that help them learn how to navigate their socio–cultural environments in safe simulations [19]. Furthermore, research suggests that long exposure to natural outdoor environmental lighting (i.e., sunlight) may have a beneficial impact on children’s behavioural and cognitive development [20,21]. The affordances of the natural outdoor environment such as open fields, trees, vegetation, and hilly terrain encourage children to be physically active, imaginative, expressive, and to explore their surroundings, having a beneficial impact on their social skills, mental wellbeing, and cognitive outcomes [1,13,19,22,23].

Risk-taking during play exposes children to excitement, uncertainty, and sometimes the possibility of injury [24,25]. Through observations and interviews, researchers have identified eight categories of risky play: play with great heights; play with high speed; play with dangerous tools; play near dangerous elements; rough-and-tumble play; play where children go exploring alone; play with impact; and vicarious play [24,25,26]. By challenging themselves during play, children can manage uncertainties while avoiding excessive risk taking, helping them to develop the skills required to support their increasing autonomy and independence [27]. Nonetheless, although risky play is supported within the Scottish Government’s resources (My World Outdoors [28]), support of this type of play behaviour, and others, varies based on practitioners’ beliefs and understanding of outdoor nature-based play and learning provision [29]. The authors are not aware of any attempt in the literature to explore play behaviours and risk-taking opportunities among children attending urban ELC settings in Scotland.

The role of the practitioner is crucial for supporting quality outdoor play and learning experiences for children, since their beliefs and attitudes influence their practice and values [3,29]. This has implications for how children utilise their outdoor space and the type of outdoor space children have access to (e.g., forest, park, structured outdoor playground). Furthermore, training for practitioners in the provision of outdoor play and learning is not universal, and attitudes and beliefs towards how outdoor nature-based provision should be incorporated into everyday practice varies [30]. Therefore, it is important to understand how practitioners within these ELC settings perceive the ability to incorporate outdoor play and learning within their regular everyday practice.

Most of the research investigating the relationship between nature-based play provision and children’s health outcomes targets older children (greater than 7 years); there is less available evidence for children in the early years (0 to 7 years) within the preschool/kindergarten setting. Much of the available evidence for this population and context suffer from poor methodological quality due to poorly designed evaluations [10,17]. These evaluations are often uncontrolled interventions or cross-sectional studies, with small sample sizes, limited reporting of confounding variables, and poor reporting of the reasons for participant withdrawal, leading to results with a high risk of bias. Evaluations in this field require more sound methodology that can be more effectively achieved by firstly assessing the feasibility of potential evaluation designs.

Feasibility studies have been carried out in British ELC settings before; however, they have focused on interventions specifically targeting obesity prevention through PA and/or healthy eating [31,32,33]. As far as the authors are aware, there has not yet been any formal robust evaluation of outdoor nature-based play and learning provision in the British early years sector. However, such an evaluation has several unique uncertainties that firstly require examination within a feasibility study, including recruiting ELC settings that provide nature-based play and learning, recruitment of participants in these settings, participant randomisation processes, and outcome measures.

In Scotland, all 3- and 4-year-old children (and eligible 2-year-olds) are entitled to 1140 h of funded ELC per year [34]. This is part of the Scottish Government’s commitment to reduce the educational attainment gap and social inequalities in Scotland by providing families with equal access to early years childcare. In 2021, 97% of eligible children were registered for funded ELC [35]. Therefore, the centre-based childcare setting is an opportunity to support the development of lifelong healthy behaviours at the population level.

The ELC sector in Scotland provides several formal settings where play and learning take place. They provide different opportunities for exposure to the outdoors with a variety of activities children can engage in while outdoors. These include:

- (i).

- Fully outdoor setting, where children spend most of their time in a forest or park with many natural affordances;

- (ii).

- Indoor/outdoor, where children can move freely between the indoor and outdoor area of their ELC setting;

- (iii).

- (Satellite, where the ELC has a nature space (e.g., forest or park), but it is not on their physical premises;

- (iv).

- Traditional ELC setting, often attached to a primary school, where children spend most of their time indoors but with the opportunity to experience the outdoor environment (built and/or natural) as part of structured sessions or play breaks.

The objective of the current feasibility study is to trial a quasi-experimental non-equivocal control design using three models of outdoor play and learning provision in the Scottish early years sector: fully outdoors, satellite, and traditional ELC settings. The aim of this study is to determine whether prespecified criteria associated with the feasibility and acceptability of the program and trial design methods are met sufficiently to progress to a full powered effectiveness evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

The reporting of this protocol has endeavoured to follow the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement (see Supplementary Table S1) [36]. We took a systematic pre-evaluation approach to designing this feasibility study by carrying out two initial phases to identify the most appropriate research questions.

2.1. Initial Phases

2.1.1. Phase One: Development of Logic Model

Using secondary data analysis and triangulation methodology, we developed a Theory of Change (ToC) of how nature-based ELC functions in a Scottish urban city, Glasgow. We triangulated interview and focus group transcripts of parents whose children attended nature-based ELC settings in the West of Scotland, observation schedules of children playing outdoors at nature-based ELC settings in the West of Scotland, and international studies investigating the relationship between nature-based ELC settings and children’s health and wellbeing outcomes from several high-income countries. This approach allowed us to explicitly state the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and underlying assumptions associated with the delivery of the programme. Further details of this process can be found elsewhere (Traynor et al., 2022). This process identified key components regarding provision of nature-based ELC that required further investigation with stakeholders before an evaluation design could be developed.

2.1.2. Phase Two: Evaluability Assessment with Key Stakeholders, Refinement of Logic Model, ToC, and Identification of Evaluation Goals

This phase followed a systematic approach to conducting an Evaluability Assessment (EA). The purpose of these EA workshops was to refine the ToC developed in Phase One, ensuring that it was still relevant to the current context (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic, rollout of 1140 h free childcare entitlement), and to identify the evaluation questions that key stakeholders would like answered regarding the provision of nature-based ELC in Scotland. These workshops took place online using MS Teams due to the government COVID-19 guidelines restricting in-person contact at the time.

During analysis of the workshop outputs, several uncertainties associated with the design of an impact evaluation were identified. These included recruitment methods of ELC settings and participants, retention rates of participants, possibility of randomisation, and type of outcome measures. These uncertainties were presented to the research steering group and a decision was made regarding how to address them. The steering group was composed of representatives from the local authority and a third sector organisation involved in the delivery of early learning and childcare in Scotland. The steering group guided the design of the research project, ensuring that the design was appropriate for the early years setting. It was decided that these uncertainties should be addressed in a feasibility study before investing finite resources into a powered effectiveness evaluation.

Six research questions were developed to be addressed in this feasibility study of nature-based ELC. Table 1 outlines these research questions along with how they will be addressed.

Table 1.

Outline of criteria, data collection tools procedures, study population, and analyses required for each research question.

2.2. Study Design

Feasibility and Pilot Study

The development of this feasibility study is based on guidance from the UK Medical Research Council for developing and evaluating complex interventions [37]. This study will pilot a quasi-experimental study design method:

A quasi-experimental non-equivalent control design using propensity score matching with multiple treatment groups. Children who attend two traditional ELC settings will be assigned to the control group and matched with children from two treatment groups: (1) 2 fully outdoors ELC settings and (2) 2 satellite ELC settings. The researchers will follow guidance on implementing propensity score methods with multiple treatment groups (e.g., 2 exposure groups and a control group) [38]. From baseline to follow-up, the study duration will be 5 weeks. Play and learning will continue as normal in both settings and the outcomes mentioned below will be measured to assess the possible impact of outdoor play and learning.

This study will employ a mixed-methods approach. Both quantitative and qualitative data will be collected to address the research questions. Alongside the piloting of these two study designs, we will carry out a process evaluation using semi-structured interviews. Qualitative methods are considered an important methodological approach to understanding the causal mechanisms of complex health interventions [39].

2.3. Ethics Approval

Ethical approval has been provided by the College of Social Science, University of Glasgow (application number: 400210145) and Glasgow City Council (reference number: 21.26).

2.4. Setting

Glasgow is the largest metropolitan area in Scotland and one of the most socioeconomically disadvantaged areas in Western Europe, with more than a third of the cities’ children estimated to be living below the poverty line [40]. The Glasgow City Council (GCC) area has one of the highest numbers of nature-based ELC settings in Scotland, with at least 18 ELC settings registered or in the process of becoming registered by the Care Inspectorate as a provider of a specific nature-based ELC model [41].

The GCC area has 110 ELC settings that are operated by the GCC Education Services and over 300 ELC settings that are privately or voluntary operated. Within these settings, there are several that are registered with the Care Inspectorate as a satellite model or are in the process of becoming registered. There are around six functioning as fully outdoor nature-based models in the GCC area, with more across Scotland. Many of these are private and voluntary childcare providers, with some functioning in partnership with GCC. Partnership providers are social enterprises that work collaboratively with GCC to extent their ELC provision. The Scottish Government’s 1140 h of free childcare entitlement is applicable to all ELC providers with the caveat that some private and partnership settings request that parents cover some additional costs. Furthermore, each setting is based in a different area of Glasgow, uses different types of green/natural spaces, and varies in size with regards to the number of attending children and practitioners. All of these factors, in addition to context, dose, and practice will influence the daily operations of each ELC setting and thus will be investigated in this feasibility and pilot study.

In the GCC local authority ELC settings, there are between 20 and 100 three- to five-year-olds registered at any one time with an average of 60 or 38 children per setting, depending on whether the ELC setting operates 50 or 38 weeks per year, respectively. In the private, voluntary, and independent sector, ELC settings have between 12 and 80 three- to five-year-olds registered, with an average of around 30 children enrolled at any one time.

2.5. Participants

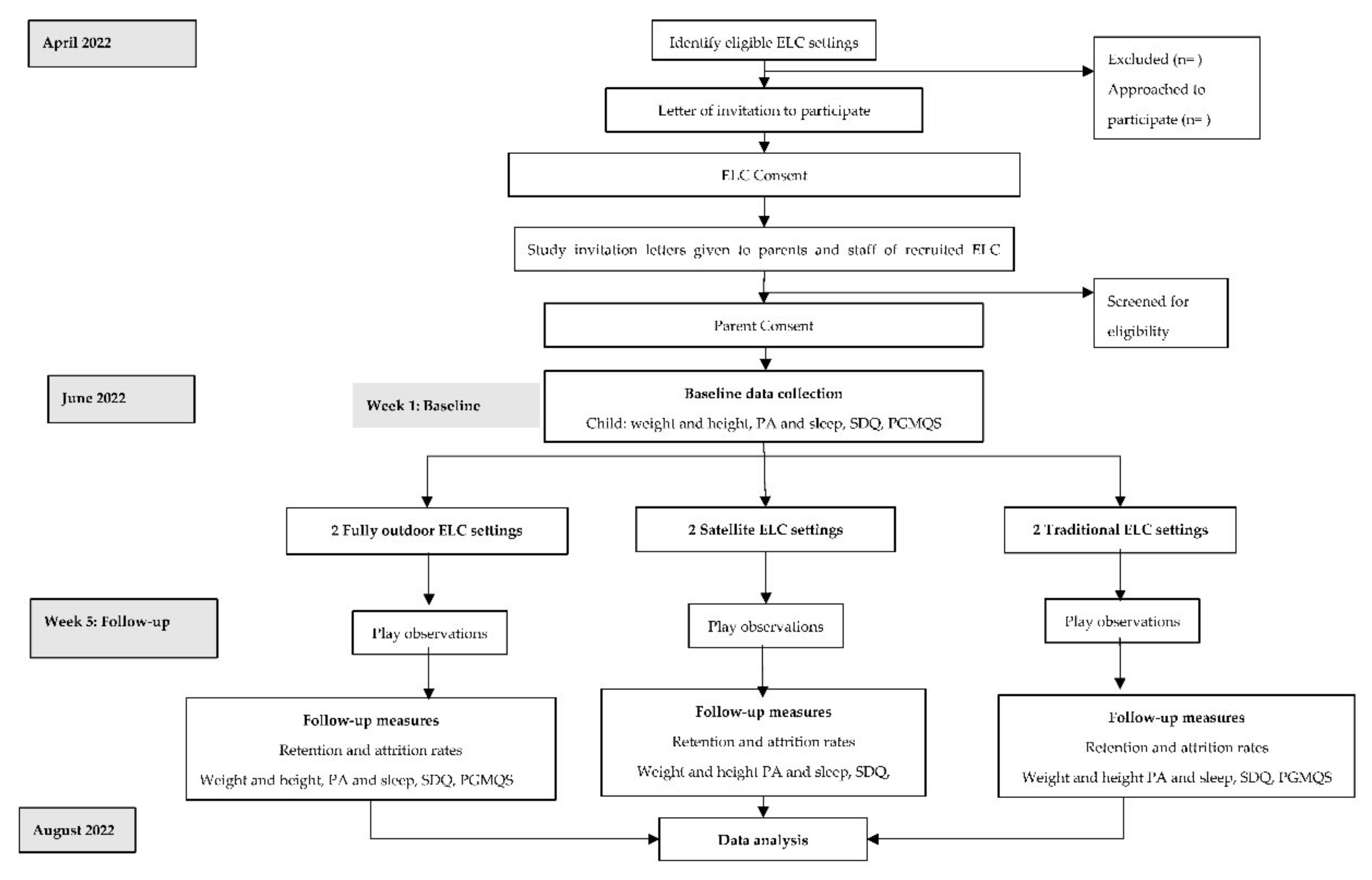

ELC settings in the GCC area, representing the different models previously mentioned, will be invited to participate in the study, including their headteacher/manager and 2 practitioners. Figure 1 illustrates the study flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. ELC—early learning and childcare; PA—physical activity; SDQ—strengths and difficulties questionnaire; PGMQS—preschool gross motor quality scale.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) are to ensure that children who are enrolled in the study are as similar as possible to children who would be enrolling in the ELC setting for the first time at the beginning of the academic year (the timepoint at which a full-scale evaluation would be recruiting). Eligible children are those who attend these ELC settings, are 3 years old, and have consent from their parent/carer to participate. Participants will receive a voucher of GBP £10 as a token of appreciation for their participation. Participating ELC settings will receive a GBP £100 donation and an additional GBP 10 for each ELC educator that participates in the interviews.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the feasibility study of nature-based ELC.

2.6. Sample Size

As this is a feasibility/pilot study, no sample size to detect between group differences was calculated. The study may provide preliminary data for the calculation of a sample size for a future full-scale evaluation. We aim to recruit 2 fully outdoor ELC settings, 2 satellite ELC settings, and 2 traditional ELC settings.

A minimum of 10 children per ELC setting will be recruited. Two practitioners and one headteacher/manager will be recruited from each ELC setting.

2.7. Recruitment

All eligible ELC settings will be contacted via email using publicly available email addresses and phone numbers. Emails will contain documents with details on the study, including the methods to be used and what will be asked of ELC settings that participate. Those that express an interest in taking part through completing an Expression of Interest Form will be followed up with a participant information sheet (PIS) and consent form. The PIS will provide further details of the methods to be used in the study and how they affect individual participation. If headteachers/managers and practitioners wish to participate, they can return the completed consent form to the research team via email. Participating ELC settings will be given study flyers to distribute to the families that attend their ELC setting. The flyers will contain a QR code for parents/carers to scan for further information on the study. The QR code will take parents/carers to a secure University of Glasgow website that has a participant information sheet and consent form for parents/carers to complete. If parents/carers would like their child to take part in the study, they can complete the consent form and email it back to the research team.

Propensity Score Matching

The propensity score is the probability of being exposed given the values of measured confounding variables [42]. In the same manner that randomisation will on average lead to measured and unmeasured covariates being balanced between study groups, assigning participants based on their propensity score will on average lead to measured baseline covariates being balanced between the study groups [43]. Our propensity score model will include all measured baseline covariates collected in the demographic survey. Participants from the traditional ELC settings (comparison) will be matched with participants from the fully outdoor settings and satellite settings (exposure) with similar propensity scores. We will use nearest neighbour matching within a specified caliper distance that is proportional to the standard deviation of the recorded covariates [43]. Once matched, the treatment effect will be determined by directly comparing the outcome data between matched samples of the exposure and comparison groups. Researchers have shown that the use of propensity score matching with small study samples can demonstrate unbiased estimations of treatment effect if the appropriate confounding variables are included in the propensity score model [44].

2.8. Measures

The feasibility questions that this study will address are shown in Table 1. RQ1 intends to address the uncertainties associated with recruitment and retention of ELC settings and study participants. The following data will be collected across all participating ELC settings:

- Number of eligible ELC settings that were approached to participate in the study.

- Number of ELC settings that expressed an interest in taking part, number of ELC settings that declined an invitation to take part, and number of ELC settings that did not respond.

- Number of eligible children who were approached to participate in the study.

- Number of children whose parents consent for them to participate and number of children who did not have consent to participate.

- Number of participating children who leave the ELC setting after the study has begun.

- Attendance records of participating children will be collected throughout the study timeline to determine retention rates.

RQ2 addresses whether matching on propensity score is feasible to detect changes in outcomes between exposure and comparison groups. This will be measured by:

- Number of children assigned a propensity score.

- Number of successful matches using propensity score.

A powered effectiveness evaluation can only be successful if its study design is able to detect differences in children’s health and wellbeing outcomes as a result of being exposed to outdoor nature-based play and learning.

Addressing RQ3 will identify which outcomes and measurement tools should be taken forward to the next stage of evaluation. This will be measured by:

- The completeness of the measurement assessments from baseline to follow-up.

- Which measurement tools demonstrate a positive, negative, or null effect between exposure and comparison groups from baseline to follow-up.

- The acceptability of the measurement tools within the study population.

The outcomes and their measurement tools can be found in Table 1.

By examining the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) tools that are currently in place across ELC settings, we can determine whether similar outcomes are recorded among all participating ELC settings (RQ4); if so, it might be possible to develop a standardised method of analysing changes in outcomes. This approach could then be used in a powered effectiveness evaluation. RQ4 will be measured by collecting a sample of M&E tools per recruited sample (n = 5), recording the outcomes that are monitored, and identifying whether analysis can be standardised.

RQ 5 and 6 will be assessed through a process evaluation using qualitative interviews. Acceptability of the programme and study design methods will be measured based on the number of major barriers discussed during semi-structured interviews with ELC headteachers and practitioners. This will be conducted using the four components of the Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) [45]. See Appendix A for the interview guide and NPT components.

NPT identifies factors that support and impede the normalisation of complex interventions into routine practice [46,47]. The theory centralises on the work that individuals and groups do to allow an intervention or programme to become normalised. NPT has four primary components: coherence (sense making, such as how easy is it to understand the purpose of outdoor nature-based play and learning?); cognitive participation (or engagement, such as are practitioners committed to providing outdoor nature-based play and learning, are they supportive of the study recruitment methods?); collective action (are practitioners sufficiently trained to provide outdoor nature-based play and learning, are they committed to ensuring children remain in their study groups?); and reflexive monitoring (formal and informal appraisal of the programme and evaluation design). By using NPT, we can optimise the study design methods (recruitment, outcome measures) by determining whether the pilot study design was acceptable for practitioners and headteachers/managers. NPT will also help us understand to what extent outdoor nature-based play and learning is considered a part of everyday practice at participating ELC settings.

The progression criteria for RQs are discussed in the next section.

2.8.1. Progression Criteria

The CONSORT 2010 extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trial guidelines recommend setting out progression criteria when reporting feasibility and pilot studies [48]. In line with recommendations, our progression criteria will be assessed using a traffic light system with varying levels of acceptability, rather than strict thresholds [49,50,51]. For example, GREEN, strong indication that study design and programme is feasible and can be taken to the next stage of evaluation; AMBER, study design and programme could be feasible with some modifications; and RED, study design and programme should not progress forward without serious consideration and modification. The progression criteria for each RQ can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Study criteria for progression to a powered effectiveness evaluation.

As demonstrated in Table 3, the progression criteria for RQ1 have been informed by previous feasibility studies in this setting, where researchers have demonstrated a recruitment rate of 32%, 37%, and 10% of eligible ELC settings, respectively [31,32,33]. Our recruitment rate of at least 30% of contacted eligible ELC settings will demonstrate that our recruitment methods for ELC settings are feasible for a larger effectiveness evaluation. Moreover, to determine the feasibility of our participant recruitment methods, we aim to have at least 50% of eligible children at fully outdoor settings return a signed consent form and 25% of eligible children at all other settings return a signed consent. These estimates are different because we believe buy-in from parents at fully outdoor ELC settings will be greater than some of the traditional and satellite settings given the nature of the research project (exploring the impact of children playing outside). Additionally, parents choose to enroll their children at fully outdoor ELCs, whereas places at council-organised settings are assigned. Finally, if 80% or more participating children are retained at the study follow-up time period, the participant recruitment methods will be considered feasible to progress to an effectiveness evaluation. If less than 50%, the pilot study will be halted and will return to the design stage. If retention rates are between 50% and 79%, then the retention methods will be reviewed to determine whether they can improve before progressing to a powered effectiveness evaluation.

The progression criteria for RQ2 are also conditional upon which traffic light criteria are achieved regarding retention rates within RQ1. The number of retained children will undergo matching based on their propensity score.

The traffic light criteria for RQ3 are based on what we determine to be sufficiently acceptable to carry out analysis of the outcome data to detect an effect if one does exist. Outcome measures that can detect a signal in effect will be considered for progression to the next stage of evaluation subject to meeting the other progression criteria. These will also be considered alongside the number of barriers mentioned related to the measures in the interviews and feedback from parents/carers. The outcomes and their measurement tools are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Outcome measurement methods for the feasibility and pilot study.

The traffic light criteria for RQ4 are based on the extent to which analysis of M&E tools can be standardised across ELC settings. It is important for researchers to maximise the use of M&E tools that are already in place to reduce the burden on practitioners, increasing the likelihood of optimal participation and supporting evaluation capacity.

Finally, the progression criteria for RQs 5 and 6 are based on the qualitative findings informed by NPT. If participants feel they have agency and resources to support outdoor play and learning and there are no major barriers associated with the study design, then progression to a powered effective evaluation will be possible after consultation with the research steering group.

2.8.2. Measurement Tools

Table 4 demonstrate the measurement tools that will be used at each timepoint. Although one timepoint is sufficient for determining the feasibility of collecting the data by researchers, there are other uncertainties that can be addressed by using two timepoints. Collecting data at both timepoints will allow us to assess the acceptability of the study design by estimating the burden of taking part in the measurements for children and also the ELC educators supporting the data collection. Additionally, we will be able to estimate potential programme effects and determine which child health outcomes should be taken forward as primary and secondary outcomes in a powered effectiveness evaluation.

Demographic Questionnaire

At baseline, parents/carers of participating children will be asked to complete an online demographic questionnaire to describe their family background (child’s date of birth, gender identity, ethnic identity, number of siblings, double or single parent household, age of mother when child was born), as well as how many hours per week the child spends at their ELC setting and their home postcode. The postcode will be used to calculate the level of multiple deprivation experienced at the local area level where the child lives as defined by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) [52]. The SIMD is a composite measure of education, crime, health, income, and housing to develop an estimate of area-based deprivation for all neigbourhoods in Scotland. The SIMD scores for participating ELC settings will also be calculated.

Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

Emotional and behavioural wellbeing will be measured using the validated parent-reported SDQ [53,54]. The parent-reported SDQ was chosen rather than the teacher-reported SDQ to reduce the burden on participating ELC settings. The SDQ has 25 items divided into 5 scales with 5 items each: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviour. Parent/carers will be asked how true different statements are about their child on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true). The total difficulties score is calculated based on all the scales excluding the prosocial scale to give a score between 0 and 40. An online version of the SDQ will be completed before the study exposure period commences and at the end of the study exposure period (follow-up).

Height and Weight

Children will have their height and weight measured at baseline across all participating ELC settings (to the nearest 0.1 cm/kg). Weight status will be presented as a BMI z-score. Children in the fully outdoor and traditional ELC setting will also have their height and weight measured at follow-up.

Preschooler Gross Motor Quality Scale (PGMQS)

Some research suggests that exposure to play and learning in nature-based ELC may have a greater benefit on certain motor skills than play and learning at traditional ELC settings alone. These associations could be more applicable to gross motor and vestibular skills, rather than object control [10]. Development of these motor skills provide the foundation for more specialised movements that can influence long-term PA levels. In our stakeholder workshops, the ELC practitioners identified several activities that are popular among children attending outdoor nature-based settings such as climbing and managing obstacles such as trees or those built by children themselves. These require important motor skills such as the ability to balance. This study will apply the balance assessment of PGMQS, a validated tool for use in 3-year-olds that assesses four components of balance: single leg standing, tandem standing, walking line forward, and walking line backward [52]. This tool has previously been used to investigate balance development in preschoolers taking part in an outdoor loose parts intervention in Nova Scotia [55]. One child will be assessed at a time; the researcher will demonstrate how to correctly perform the task and then ask the child to perform the task. They will have one practice trial followed by two scored trials. Each balance task is composed of 4 or 5 criteria as outlined in Table 5. Each criterion will be scored a 0, indicating the movement performed incorrectly, or 1, indicating the movement performed correctly, to get a total balance score out of 18. The two scored trials will be added to give a total score out of 36. Measures will be collected at baseline and follow-up (5 weeks).

Table 5.

Balance tasks using the preschool gross motor quality scale (adapted from Sun et al., 2010).

Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Sleep

Children’s physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep will be measured using a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer (Axivity AX3). Wrist-worn devices have been found to be more acceptable and less burdensome compared with hip-worn devices [56]. Preliminary piloting of the Axivity devices with a small sample of 3-year-olds for 3 days has found high levels of acceptability and compliance. Children will be asked to wear the activity monitor on their non-dominant wrist to limit miscalculated activity counts during sedentary behaviours (e.g., drawing, writing, and playing on mobile electronic devices) [57]. The devices will be configured to record raw acceleration data using Open Movement GUI (OMGUI, V1.0.0.43). Parents/carers will be asked to ensure that their child wears the device for 7 days (24 h/day) with a minimum of 3 consecutive days, removing it only if it causes discomfort or when the child is in water (e.g., swimming or bathing). Parents/carers will be provided with an activity diary to log any time the device is removed from their child’s wrist, the reason why, and the time it is placed back on their child’s wrist. The devices will be programmed to start at the end of the day when anthropometric measures and motor skills assessment are completed. Age-appropriate cut points will be applied to the data to identify activity intensities. Physical activity intensity cut points vary depending on the type of activity monitor used (e.g., ActiGraph, GENEActive, Axivity), the location on the body where it is mounted (e.g., wrist, waist, or thigh), and the age group of the study population. There is not yet a consensus regarding a standard approach to analysing PA by accelerometer [58,59]. Moreover, Axivity monitors have not yet been validated in the preschool-aged population [60]. Research suggests that due to the sporadic activity pattern of preschool-aged children, shorter epoch lengths (5-s epoch) at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz may be more suitable to identify very short periods of movement [61]. Therefore, based on recent research using wrist-worn accelerometers with preschoolers, our PA intensity thresholds are: sedentary behaviour, ≤221 counts per 5-s epoch; light PA, 222–729 counts per 5-s epoch; MVPA ≥ 730 counts per 5-s epoch; and total PA ≥ 222 [62]. These cut points have been used in wrist-worn accelerometers in a similar Scottish ELC setting [63]. The light sensor on the Axivity monitor is a logarithmic lux sensor (a measure of the intensity of light) that has a wavelength characteristic similar to the human eye. It is recommended that the AX3 monitor is calibrated at 1000 lux [64].

Sleep will be estimated by calculating the sleep period time (SPT) frame, the time window from initial sleep onset and waking up after the last sleep episode of the night, based on z-angle variance [65,66]. Using this, the average time of sleep onset and waking (beginning and end of SPT window) will be calculated. The total period of continuous inactivity periods (no change in z-angle of >5° for a minimum of 5 min) within the SPT-window will be calculated to estimate sleep duration per night, then averaged across available nights [66]. A minimum wear time of 3 complete days will be required for analysis. There is not yet a standard recommendation for non-wear time among preschool-aged children [61]. Therefore, we will define the device as not being worn if there are 60 consecutive minutes of zero acceleration recorded. This will be cross-checked with the activity logs to identify any non-wear time less than 60 min.

Play Behaviour

A base map of the outdoor space (a geographical mapped representation) used by each ELC setting will be developed for recording children’s play behaviours using Google Maps. A base map allows observers to document the physical features and layout of the outdoor environment such as vegetation, play structures, and pathways [23]. The Tool for Observing Play Outdoors (TOPO) will be used to code pre-determined play types onto the base map of the outdoor space [19]. This study will use a place-based protocol to assess the quality of the environment for supporting play types [23]. A pre-defined observation zone will be scanned clockwise until a play event is detected. The researcher then observes the child(ren) for around 15 s, records the play behaviours, and maps the event onto the base map. Afterwards, scanning of the observation zone begins again from the point that it stopped, until another play event is detected. Only data from children who have consent from their parent/carer to participate will be recorded. The expanded TOPO-32 version will be used to assess the feasibility of fully completing the data collection tool. The tool has 9 primary play types: physical play, exploratory play, imaginative play, play with rules, bio play (interactions with the natural environment), expressive play, restorative play, digital play, and non play, along with 32 associated subtypes. The TOPO-32 assigns primary-subtype combinations for each observed play episode alongside peer, adult, and environmental interaction codes. For each play episode, two primary-subtype combinations will be recorded. Additional categories will be added to the observation tool such as risk taking during play. Our observation protocol will use the play categories defined by Sandseter and colleagues (Table 6) as these are considered the most suitable approach for identifying the risk-taking affordances [24,25,26]. Appendix B has an example of the observation protocol to be used in the study.

Table 6.

Categories of risky play (adapted from [24,25,26]).

Semi-Structured Interviews

Using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A), developed using the Normalisation Process Theory, acceptability of the programme and study design methods will be assessed with ELC headteachers and practitioners. Interviews will cover participants’ views on the implementation of nature-based ELC (e.g., staff support, access to training and resources, contextual factors that influence implementation such as weather) and acceptability of the study design methods (how easy/difficult ensuring children remain in assigned groups, are data collection methods too intrusive, did the presence of an external researcher impact delivery of the programme in any way). Interviews will last one hour and take place in person or over the phone, whichever is most convenient to the participant. Interviews will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Monitoring and Evaluation Tools

Our EA workshops identified several data collection methods that are already in place within ELC settings to record children’s progress throughout their time at the settings. These are known as online journals. A sample of these data collection methods will be requested from participating children. The online journals will be examined to check for similarities of the type of information recorded and to determine whether standardised analysis may be implemented across the online journals from each ELC setting. A sub-sample of 5 participants from each participating ELC setting will be selected at random. OT will ask the headteacher/manager for access to the information collected within the online journals of children who have consent from their parents. An Excel spreadsheet will be developed based on the information extracted from the online journals. This information will include what outcomes are recorded, how many times, and by whom.

2.9. Analysis

2.9.1. Data Management

All data will be stored in a secure storage system at the Social and Public Health Sciences Unit (SPHSU), University of Glasgow. The raw data will only be accessible to the immediate research team. Consent forms will be stored separately from participant data and a unique identification code will be assigned to each participant and ELC setting. Raw data such as interview recordings and identifiable transcripts will be securely deleted at the end of the project timeline. The de-identified data will be stored for up to 10 years and be available to researchers who are interested and have relevant ethical approval in an anonymised format in line with the University of Glasgow retention policy and general data protection regulation.

2.9.2. Recruitment

The feasibility of the recruitment methods and retention rates will be determined by calculating the proportion of children measured at baseline and follow-up. Participant characteristics of those who complete the study and those who drop out will be investigated to determine any sources of bias.

2.9.3. Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the children and ELC settings will be summarised descriptively using means and standard deviations. For outcome measures: medians and interquartile ranges will be calculated for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The summary statistics will be examined alongside demographic variables to inform the sample size and recruitment methods for the full-scale evaluation. Comparisons will be made by the SIMD level of ELC settings. Any missing data will be described to inform the full-scale evaluation. STATA statistical software will be used for all analyses.

Exploratory inferential analysis using ANOVA and linear regression will be performed within the study population of each ELC setting. Analysis will include a covariate adjustment based on the confounding variables collected in the demographic survey (e.g., gender, SIMD score, ethnicity, etc.) and covariate adjustment using children’s physical activity levels, since higher levels of PA are known to positively influence mental wellbeing.

Using propensity score matching, we will estimate the average treatment effect (ATE) of attendance at nature-based ELC on each health and wellbeing outcome (e.g., PA). A logistic model will predict each participant’s propensity score using the covariates collected in the demographic survey. The ATE on an outcome will be estimated by matching participants to another participant whose propensity score is within the pre-specified caliper distance.

2.9.4. Qualitative Analysis

The interviews will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by an approved transcription service. Thematic analysis will be applied to code the data based on the pre-determined process evaluation topics (feasibility components) [67]. NVivo 12 will be used to analyse the transcripts (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2020). Transcripts will first be read and initial codes created based on the interview questions and research aims. OT will develop a preliminary coding framework and discuss this with PM, NRC, and AM. Themes and sub-themes will be created both deductively and inductively, while making sure the theme labels remain representative of the data. To reduce bias, a sub-sample of the transcripts will be reviewed by a co-author and any discrepancies will be discussed and resolved. After all themes have been created, matrices will be developed to view responses and frequency of themes amongst the transcripts. To ensure rigour in the research, OT will engage in reflexive thinking throughout the research process. This will include discussing uncertainties with co-authors and constantly returning to the literature to elucidate particular themes or experiences. OT will endeavour to have spacing between interviews to allow for reflection and learning from each interview. To encourage participants to feel comfortable, interviews will be arranged for mutually convenient times and (if applicable) locations.

3. Discussion

The evidence base underpinning the effectiveness of nature-based play and learning provision suffers from poor methodological quality caused by a lack of well-designed evaluations [10]. We argue that evaluations can be better designed if a feasibility and pilot study is first carried out to address key uncertainties that may compromise a fully powered effectiveness evaluation. Feasibility studies are important for estimating recruitment and retention rates, data collection procedures and analysis, and acceptability of the programme [50]. The recent updated Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on evaluating complex interventions recommends that key uncertainties should be investigated in a feasibility study and assessed against predefined progression criteria associated with the evaluation design and acceptability of the programme [37]. This in turn will ensure that finite resources are not wasted on under-powered large-scale evaluations. As outlined in this paper, this study will address key feasibility questions identified through programme theory work (Phase 1; Traynor et al., 2022) and collaborative engagement with key stakeholders (Phase 2; Evaluability Assessment). These include, recruitment and retention procedures, outcome measurement methods and analysis, and statistical matching procedures. Propensity score matching is a valuable method when randomisation is not possible within the study contexts [38]. Propensity score matching reduces the impact of bias on the outcomes under investigation by controlling for measured covariates. Nonetheless, this method does have its limitations such as the possibility of unmeasured covariates influencing the outcome of interest. Furthermore, our embedded process evaluation demonstrates a reliable theory-based approach for determining the acceptability of the study design methods and provision of the programme using NPT. Moreover, having pre-specified progression criteria based on a traffic light system for each research question demonstrates an explicit process to decide whether to proceed, proceed with modifications, or not to proceed for each trial procedure and programme [68].

Beyond addressing key feasibility aspects, our findings will have implications for the wider field of nature-based ELC research and any future fully powered effectiveness evaluation of outdoor nature-based ELC in Scotland. At present, evaluations often have a poor description of the dose and quality of their nature exposure element, making it difficult to determine the pathways by which nature-based ELC influence child health outcomes [15,18]. The present study has three clearly defined models of ELC (traditional, fully outdoors, and satellite) that differ in their provision of outdoor play and learning (e.g., time spent outdoors, number of children outdoors per session, and outdoor space used). Additionally, our observational methods and interviews will provide further detail regarding the affordances of each outdoor location with regards to environmental features and play behaviours. Therefore, alongside Gibson’s Theory of Affordances [69], these procedures will help a full-scale evaluation develop hypothesised pathways with outcomes to identify an effect, if one does exist. Furthermore, the role of the practitioner is also crucial within the provision of nature-based ELC [29]. Recent research has highlighted the need for more systems-based approaches with ELC practitioners to identify the factors important for implementing nature-based ELC (Zucca et al., under review). Our interviews with ELC practitioners and headteachers will contribute to our understanding of the specific pedagogical practices and contextual factors that influence how ELC educators support children’s outdoor nature-based play and learning experiences in nature. Finally, our findings will help policy makers and local authority decision makers optimise the resources they have by encouraging reflection on their current practice.

4. Conclusions

To support the implementation of outdoor nature-based ELC provision it is important for researchers to work collaboratively with practitioners and policy makers across the early years sector. This paper has demonstrated how we have developed a feasibility and pilot study to evaluate the provision of outdoor nature-based ELC, informed by collaborative engagement with key stakeholders and a research steering group. Our findings will demonstrate whether a quasi-experimental study design using propensity score matching is feasible and acceptable to take forward to a fully powered effectiveness evaluation. Furthermore, we will be able to identify to what extent outdoor play and learning provision has been normalised within early years practice and whether there are any key barriers to further normalising the provision of outdoor nature-based play and learning within Glasgow’s ELC settings. By involving our steering group within the decision-making process, these findings can help inform the implementation and subsequent evaluation of nature-based ELC settings across other parts of Scotland and the UK.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19127461/s1, Table S1: SPIRIT Checklist.

Author Contributions

O.T., P.M., N.R.C. and A.M., contributed to the conceptualisation and theoretical underpinning of the manuscript; O.T., developed the study design and drafted and finalised the manuscript; P.M., N.R.C. and A.M., reviewed, commented, and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

OT was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (funding code MC_ST_00022). AM was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and Scottish Chief Scientific Officer (grant numbers MC_UU_12017/14, MC_UU_00022/1, SPHSU14, SPHSU16). PM was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and Scottish Chief Scientific Officer (grant numbers MC_UU_12017/10, MC_UU_00022/4; SPHSU10, SPHSU19). NRC was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and Scottish Chief Scientific Officer (grant numbers MC_UU_00022/2, SPHSU17).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval has been granted by the Ethics Committee of the College of Social Sciences, University of Glasgow (application reference: 400210145, date of approval: 1 April 2022) and Glasgow City Council Education Services (application reference: 21.26, date of approval: 31 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent will be obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The quantitative and qualitative data collected will be held in an anonymised format in a UK Research Data Repository. The study’s results will be available to participants, healthcare professionals, the public, and other interested groups via a PhD thesis and Open Access journal articles.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the ELC staff members who took part in the online workshops (during the second initial phase) that informed the development of this study. They thank their colleague Avril Johnstone for her contribution during the first initial phase and Jessica Kenny, who was a fourth-year undergraduate intern who collected the field work data that supported the development of the logic model in Phase One. They also thank their research study steering group made up of representatives from Glasgow City Council Early Years Sector and Inspiring Scotland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Interview Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews

| Assessing the Acceptability of Programme and Trial Methods | Purpose of Question | Normalisation Process Theory Component |

|---|---|---|

| Address participant’s views regarding implementation of the programme, identify whether participant’s views match with those from the EA workshops and findings in the literature. Can help direct data collection for full-scale evaluation. | Coherence (e.g., how easy is the programme to describe, do participants believe the programme has a clear purpose, who does the programme benefit, how does it fit with the overall goals of early years provision?) |

| Address implementation aspects of the programme, what is working and what is not. Support recommendations to stakeholders regarding how programme can be improved. | Cognitive participation (e.g., are participants committed to providing the programme, do participants believe that providing the programme is a good use of their time?) Collective action (e.g., do participants believe they are sufficiently trained to provide the programme, do they have the resources they require, is it compatible with existing work practices?) |

| Identify contextual factors that influence the implementation of the programme. | Reflexive Monitoring (e.g., participants are able reflect and critique the programme.) |

| Assess the acceptability of the study methods. | Coherence (i.e., are educators understanding of why the trial design methods have been used?) Cognitive participation (i.e., were educators supportive of the recruitment methods?) Collective action (i.e., did the study design have any impact on usual practice?) Reflexive monitoring of the trial methods is ongoing throughout the study through educator feedback and as part of the interviews. |

| Assess the acceptability of data collection methods. Identify which methods can be taken forward to a full-scale evaluation. | Coherence (i.e., do participants understand why these data collection methods are being used, how they might contribute to future implementation of the programme?) Cognitive action (i.e., were educators prepared to assist in the data collection methods, were children happy to participate?) Collective action (i.e., did educators believe they were skilled enough to support data collection, were they happy to share current monitoring and evaluation practices?) Reflexive monitoring (i.e., did participants believe that the outcomes the measurement tools were assessing important for programme implementation?) |

Appendix B. Play Observation Protocol (Adapted from Loebach and Cox 2020; Litlle, 2010)

| Variable | Code |

|---|---|

| Event | Play event number |

| Participant | Unique ID |

| Play type | (1) Physical; (2) Exploratory; (3) Imaginative; (4) Play with rules; (5) Bio/nature; (6) Expressive; (7) Restorative; (8) Digital; (9) Non-play |

| Risky behaviour/play | (1) Heights; (2) Speed; (3) Dangerous tools (4) Dangerous elements (5) Rough and tumble (6) Exploring alone (7) Impact (8) Vicarious |

| Peer interaction | (1) Solitary; (2) Parallel; (3) Cooperative; (4) Onlooking; (5) Conflict; (6) Unoccupied |

| Adult interaction | (1) No adult presenting/observing; (2) Observing; (3) Participating; (4) Directing; (5) Restricting; (6) Other |

| Environmental interaction | (LN) Loose natural; (FN) Fixed natural; (LM) Loose manufactured; (FM) Fixed manufactured |

| Play communication | (1) Play; (2) Environment; (3) Peer-social; (4) Adult-social; (5) Cowabunga!; (6) Wayfinder; (7) Instructive; (8) Care; (9)Permission seeking; (10); Self-talk; (11) Conflict |

| Interaction with coder | Yes; No |

| Open Coding | Descriptive texts |

References

- Tremblay, M.; Gray, C.; Babcock, S.; Barnes, J.; Costas Bradstreet, C.; Carr, D.; Chabot, G.; Choquette, L.; Chorney, D.; Collyer, C.; et al. Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6475–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Felix, E.; Silva, V.; Caetano, M.; Ribeiro, M.V.; Fidalgo, T.M.; Rosa Neto, F.; Sanchez, Z.M.; Surkan, P.J.; Martins, S.S.; Caetano, S.C. Excessive Screen Media Use in Preschoolers Is Associated with Poor Motor Skills. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Cordovil, R.; Hagen, T.L.; Lopes, F. Barriers for Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Institutions: Perception of Risk in Children’s Play among European Parents and ECEC Practitioners. Child Care Pract. 2020, 26, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D.A. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Atherton, F.; McBride, M.; Calderwood, C. Physical Activity Guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Hesketh, K.R.; McMinn, A.M.; Ekelund, U.; Sharp, S.J.; Collings, P.J.; Harvey, N.C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Inskip, H.M.; Cooper, C.; van Sluijs, E.M. Objectively measured physical activity in four-year-old British children: A cross-sectional analysis of activity patterns segmented across the day. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tinner, L.; Kipping, R.; White, J.; Jago, R.; Metcalfe, C.; Hollingworth, W. Cross-sectional analysis of physical activity in 2-4-year-olds in England with paediatric quality of life and family expenditure on physical activity. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Ridgers, N.D.; Howard, B.J.; Winkler, E.A.; Healy, G.N.; Owen, N.; Dunstan, D.W.; Salmon, J. Light-Intensity Physical Activity and Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in US Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doré, I.; Sylvester, B.; Sabiston, C.; Sylvestre, M.P.; O’Loughlin, J.; Brunet, J.; Bélanger, M. Mechanisms underpinning the association between physical activity and mental health in adolescence: A 6-year study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, A.; McCrorie, P.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; Martin, A. Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare—Influence on Children’s Health, Wellbeing and Development: Literature Review; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/systematic-literature-review-nature-based-early-learning-childcare-childrens-health-wellbeing-development/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Janssen, X.; Martin, A.; Hughes, A.R.; Hill, C.M.; Kotronoulas, G.; Hesketh, K.R. Associations of screen time, sedentary time and physical activity with sleep in under 5s: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2020, 49, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, S.; Bruijns, B.A.; Vanderloo, L.M.; O’Brien, K.T.; Johnson, A.M.; Tucker, P. Physical activity and sedentary time during childcare outdoor play sessions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2018, 108, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L.; Kjeldsted, E.; Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Bentsen, P. Mental, physical and social health benefits of immersive nature-experience for children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. Health Place 2019, 58, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrorie, P.; Olsen, J.R.; Caryl, F.M.; Nicholls, N.; Mitchell, R. Neighbourhood natural space and the narrowing of socioeconomic inequality in children’s social, emotional, and behavioural wellbeing. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A.; McCrorie, P.; Cordovil, R.; Fjørtoft, I.; Iivonen, S.; Jidovtseff, B.; Lopes, F.; Reilly, J.J.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; et al. Nature-Based Early Childhood Education and Children’s Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, Motor Competence, and Other Physical Health Outcomes: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeland, J.; Moens, M.A.; Beute, F.; Assink, M.; Staaks, J.P.; Overbeek, G. A dose of nature: Two three-level meta-analyses of the beneficial effects of exposure to nature on children’s self-regulation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankiw, K.A.; Tsiros, M.D.; Baldock, K.L.; Kumar, S. The impacts of unstructured nature play on health in early childhood development: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, A.; Martin, A.; Cordovil, R.; Fjørtoft, I.; Iivonen, S.; Jidovtseff, B.; Lopes, F.; Reilly, J.J.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; et al. Nature-Based Early Childhood Education and Children’s Social, Emotional and Cognitive Development: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J.; Cox, A. Tool for observing play outdoors (Topo): A new typology for capturing children’s play behaviors in outdoor environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Bekkhus, M.; Borge, A.I. Time spent outdoors during preschool: Links with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V.S.; Czajkowski, N.O.; Staton, S.; Smith, S.; Pattinson, C.; Allen, A.; Thorpe, K.; Bekkhus, M. Environmental light exposure, rest-activity rhythms, and symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity: An observational study of Australian preschoolers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Loebach, J.; Little, S. Understanding the Nature Play Milieu: Using Behavior Mapping to Investigate Children’s Activities in Outdoor Play Spaces. Child. Youth Environ. 2018, 28, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Characteristics of risky play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kleppe, R. Outdoor Risky Play. 2019. Available online: https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/outdoor-risky-play (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Kleppe, R.; Melhuish, E.; Sandseter, E.B.H. Identifying and characterizing risky play in the age one-to-three years. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 25, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Inspectorate. My World Outdoors; Care Inspectorate: Dundee, Scotland, 2016; Available online: https://hub.careinspectorate.com/how-we-support-improvement/care-inspectorate-programmes-and-publications/my-world-outdoors/ (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Howe, N.; Perlman, M.; Bergeron, C.; Burns, S. Scotland Embarks on a National Outdoor Play Initiative: Educator Perspectives. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 32, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, M.; Howe, N.; Bergeron, C. How and Why Did Outdoor Play Become a Central Focus of Scottish Early Learning and Care Policy? Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 23, 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, S.E.; Akhtar, S.; Jackson, C.; Bingham, D.D.; Hewitt, C.; Routen, A.; Richardson, G.; Ainsworth, H.; Moore, H.J.; Summerbell, C.D.; et al. Preschoolers in the Playground: A pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of a physical activity intervention for children aged 18 months to 4 years. Public Health Res. 2015, 3, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kipping, R.; Langford, R.; Brockman, R.; Wells, S.; Metcalfe, C.; Papadaki, A.; White, J.; Hollingworth, W.; Moore, L.; Ward, D.; et al. Child-care self-assessment to improve physical activity, oral health and nutrition for 2- to 4-year-olds: A feasibility cluster RCT. Public Health Res. 2019, 7, 1–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malden, S.; Reilly, J.J.; Gibson, A.M.; Bardid, F.; Summerbell, C.; De Craemer, M.; Cardon, G.; Androutsos, O.; Manios, Y.; Hughes, A. A feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a preschool obesity prevention intervention: ToyBox-Scotland. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scottish Government. Early Education and Care; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/early-education-and-care/ (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Scottish Government. Summary Statistics for Schools in Scotland 2021; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/summary-statistics-schools-scotland/pages/6/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Chan, A.W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Altman, D.G.; Mann, H.; Berlin, J.A.; Dickersin, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Schulz, K.F.; Parulekar, W.R.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013, 346, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccaffrey, D.F.; Griffin, B.A.; Almirall, D.; Slaughter, M.E.; Ramchand, R.; Burgette, L.F. A Tutorial on Propensity Score Estimation for Multiple Treatments Using Generalized Boosted Models. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonell, C.; Warren, E.; Melendez-Torres, G. Methodological reflections on using qualitative research to explore the causal mechanisms of complex health interventions. Evaluation 2022, 28, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow Centre for Population Health. Money and Work 2021. Available online: https://www.gcph.co.uk/money_and_work. (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Care Inspectorate. Early Learning and Childcare: Delivering High Quality Play and Learning Environments Outdoors; Communications: Dundee, Scotland, 2018; Available online: https://www.careinspectorate.com/index.php/news/4681-early-learning-and-childcare-practice-note (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pirracchio, R.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Chevret, S. Evaluation of the Propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratios in case of small sample size. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.; Finch, T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology 2009, 43, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Treweek, S.; Pope, C.; MacFarlane, A.; Ballini, L.; Dowrick, C.; Finch, T.; Kennedy, A.; Mair, F.; O’Donnell, C.; et al. Normalisation process theory: A framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, C.R.; Cummings, A.; Girling, M.; Bracher, M.; Mair, F.S.; May, C.M.; Murray, E.; Myall, M.; Rapley, T.; Finch, T. Using Normalization Process Theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hallingberg, B.; Turley, R.; Segrott, J.; Wight, D.; Craig, P.; Moore, L.; Murphy, S.; Robling, M.; Simpson, S.A.; Moore, G. Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: A systematic review of guidance. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Naylor, P.J.; Ashe, M.C.; Fernandez, M.; Yoong, S.L.; Wolfenden, L. Guidance for conducting feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/collections/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Sun, S.H.; Zhu, Y.C.; Shih, C.L.; Lin, C.H.; Wu, S.K. Development and initial validation of the Preschooler Gross Motor Quality Scale. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 31, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The strength and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunissen, M.H.; Vogels, A.G.; de Wolff, M.S.; Crone, M.R.; Reijneveld, S.A. Comparing three short questionnaires to detect psychosocial problems among 3 to 4-year olds. BMC Pediatrics 2015, 15, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branje, K.; Stevens, D.; Hobson, H.; Kirk, S.; Stone, M. Impact of an outdoor loose parts intervention on Nova Scotia preschoolers’ fundamental movement skills: A multi-methods randomized controlled trial. AIMS Public Health 2021, 9, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S.J.; Noonan, R.; Rowlands, A.V.; Van Hees, V.; Knowles, Z.R.; Boddy, L.M. Wear compliance and activity in children wearing wrist- and hip-mounted accelerometers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; McDonough, D.J.; Zeng, N.; Lee, J.E. The Dilemma of Analyzing Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior with Wrist Accelerometer Data: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Schmutz, E.A.; Zysset, A.E.; Kakebeeke, T.H.; Messerli-Bürgy, N.; Stülb, K.; Arhab, A.; Meyer, A.H.; Munsch, S.; Jenni, O.G.; et al. Accelerometer-derived physical activity estimation in preschoolers—Comparison of cut-point sets incorporating the vector magnitude vs. the vertical axis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, T.M.; de Vries, L.; op den Buijsch, R.; Eyre, E.; Dobell, A.; Duncan, M.; Chinapaw, M.J. Cross-validation of cut-points in preschool children using different accelerometer placements and data axes. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craemer, M.; Decraene, M.; Willems, I.; Buysse, F.; Van Driessche, E.; Verbestel, V. Objective measurement of 24-h movement behaviors in preschool children using wrist-worn and thigh-worn accelerometers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migueles, J.H.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Ekelund, U.; Delisle Nyström, C.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Löf, M.; Labayen, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B. Accelerometer Data Collection and Processing Criteria to Assess Physical Activity and Other Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Practical Considerations. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1821–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.; Ekelund, U.; Nero, H.; Marcus, C.; Hagströmer, M. Calibration and cross-validation of a wrist-worn Actigraph in young preschoolers. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hislop, J.; Palmer, N.; Anand, P.; Aldin, T. Validity of wrist worn accelerometers and comparability between hip and wrist placement sites in estimating physical activity behaviour in preschool children. Physiol. Meas. 2016, 37, 1701–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Axivity. AX3 User Manual; Axivity Ltd.: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2015; Available online: https://axivity.com/userguides/ax3/settings/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Van Hees, V.T.; Sabia, S.; Jones, S.E.; Wood, A.R.; Anderson, K.N.; Kivimäki, M.; Frayling, T.M.; Pack, A.I.; Bucan, M.; Trenell, M.I.; et al. Estimating sleep parameters using an accelerometer without sleep diary. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, L.M.; Sangha, N.; Wyse, C.; Hindle, E.; Haughton, D.; Campbell, K.; Brown, J.; Moore, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Inchley, J.C.; et al. Accelerometry-assessed sleep duration and timing in late childhood and adolescence in Scottish schoolchildren: A feasibility study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, M.; Bromley, K.; Sutton, C.J.; McCray, G.; Myers, H.L.; Lancaster, G.A. Determining sample size for progression criteria for pragmatic pilot RCTs: The hypothesis test strikes back! Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Affordances and the Body: An Intentional Analysis of Gibson’s Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1989, 19, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).