Abstract

Background: Person-centered care (PCC) requires knowledge about patient preferences. This formative qualitative study aimed to identify (sub)criteria of PCC for the design of a quantitative, choice-based instrument to elicit patient preferences for person-centered dementia care. Method: Interviews were conducted with n = 2 dementia care managers, n = 10 People living with Dementia (PlwD), and n = 3 caregivers (CGs), which followed a semi-structured interview guide including a card game with PCC criteria identified from the literature. Criteria cards were shown to explore the PlwD’s conception. PlwD were asked to rank the cards to identify patient-relevant criteria of PCC. Audios were verbatim-transcribed and analyzed with qualitative content analysis. Card game results were coded on a 10-point-scale, and sums and means for criteria were calculated. Results: Six criteria with two sub-criteria emerged from the analysis; social relationships (indirect contact, direct contact), cognitive training (passive, active), organization of care (decentralized structures and no shared decision making, centralized structures and shared decision making), assistance with daily activities (professional, family member), characteristics of care professionals (empathy, education and work experience) and physical activities (alone, group). Dementia-sensitive wording and balance between comprehensibility vs. completeness of the (sub)criteria emerged as additional themes. Conclusions: Our formative study provides initial data about patient-relevant criteria of PCC to design a quantitative patient preference instrument. Future research may want to consider the balance between (sub)criteria comprehensibility vs. completeness.

1. Introduction

With aging populations, dementia represents a challenge for health care systems worldwide [1]. Globally, around 55 million people have dementia, and there are nearly 10 million new cases every year [2]. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 estimates Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias as the fourth-leading cause of death globally in the age group 75 years and older [3]. Currently, no curative, disease-modifying treatment for all People living with Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment [hereinafter commonly referred to as “PlwD”] exists. PlwD need a timely differential diagnosis as well as evidence-based treatment and care, which ensures a high Quality of Life (QoL) [1,4].

Person-centered care (PCC) is the underlying philosophy of the Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Practice Recommendations. A person-centered focus is viewed as the core of quality care in dementia [5]. Many countries include a PCC approach in their national guidelines and dementia plans [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. It follows a non-pharmacological, sociopsychological treatment approach and challenges the traditional clinician-centered or disease-focused medical model to instead suggest a model of care, which is customized to each person [13]. This customization requires knowledge about the recipient’s needs and preferences [14,15]. Among PlwD, some research about preferences exists, however, little is known about preferences elicited through quantitative, in particular, choice-based preference methods [16,17]. A recent literature review focused on decision-making tools with PlwD by Ho et al. [18] found that earlier studies often applied qualitative methods and Likert-type scales. Harrison Dening et al. [19] elicited preferences from dyads during qualitative interviews, van Haitsma et al. developed an extensive Likert-scale based Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory (PELI) for elicitation of preferences in community-dwelling aged adults [20]. These methods, however, fall short in quantifying, weighing and ranking patient-relevant elements of care to measure their relative importance and identify most/least preferred choices. Such information can be assessed with quantitative, choice-based preference measurement techniques from multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) [21]. Groenewoud et al. [22] addressed relevant aspects of outpatient care and support services for people with Alzheimer’s disease by application of a quantitative, choice-based preference instrument (Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE)), which, however, was carried out with patient representatives and not the patients themselves. Other MCDA techniques commonly used in health care include best–worse scaling (BWS) [23] and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [24]. The AHP, depending on the number of elements included, may require to ask many questions. DCEs, depending on the number of choice sets included (full vs. fractional factorial design), usually include fewer but cognitively more challenging questions. BWS distinguishes between three basic cases; object scaling (case 1), attribute or profile scaling (case 2) and multi-profiling (case 3), each case including various experimental designs, number of choice sets and questions. Hence, in BWS, the cognitive demands of included questions increase with each case [23]. To elicit patient preferences from people with cognitive impairments, the AHP has been suggested, as it may be more feasible than other MCDA techniques due to simple pairwise comparisons with only two individual aspects of a complex decision problem [25]. To keep the number of choice questions doable, the number of elements to include in the AHP model needs to be considered in the early development stages.

MCDA techniques, including the AHP, comprise the development of attribute/criteria-based experimental decision models for preference measurement [26,27]. The validity of an attribute/criteria-based experiment depends on the researcher’s ability to appropriately identify and specify the included criteria [24,26,27,28]. Poorly identified criteria can have negative implications for the design and conduct of AHP surveys and increase the risk of inaccurate results, which in turn can misinform potential policy implementation. The risk of bias, i.e., researcher bias, in quantitative preference measurement studies can be reduced by a rigorous, systematic, and transparently reported identification of (sub)criteria [28,29]. Several methods have been suggested for AHP development, e.g., literature reviews, existing conceptual and policy-relevant outcome measures, theoretical arguments, expert opinion reviews, professional recommendations, patient surveys, nominal group ranking techniques and qualitative research methods [24]. Coast et al. [30] emphasize the limitation of attribute and level derivation only from a review of the literature and suggest the additional application of qualitative methods for attribute elicitation. These methods include the right instruments to capture and reflect the perspective and experiences of the decision makers. Only accurately described formative qualitative studies applied to derive (sub)criteria give readers the opportunity to judge the quality of the resulting decision model for preference elicitation [29]. Despite a recent increase in publications about pertinent studies, there is still a lack of both evidence and experience.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has reported the qualitative identification of patient-relevant (sub)criteria of PCC among community-dwelling PlwD. Our study aimed to fill this gap with this rigorous process report on (sub)criteria identification for the design of a quantitative, choice-based instrument, an AHP, to elicit patient preferences for PCC among community-dwelling PlwD.

2. Methods

We followed the guidelines for reporting formative qualitative research to support the development of quantitative preference survey instruments by Hollin et al. [29].

2.1. Qualitative Approach

We applied a narrative qualitative approach to cover the PlwD’s individual experiences [31]. As this study employed a flexible strategy, characterized by the inclusion of life histories and interpretive analysis, the research paradigm followed critical realism [32].

2.2. Theoretical Framework

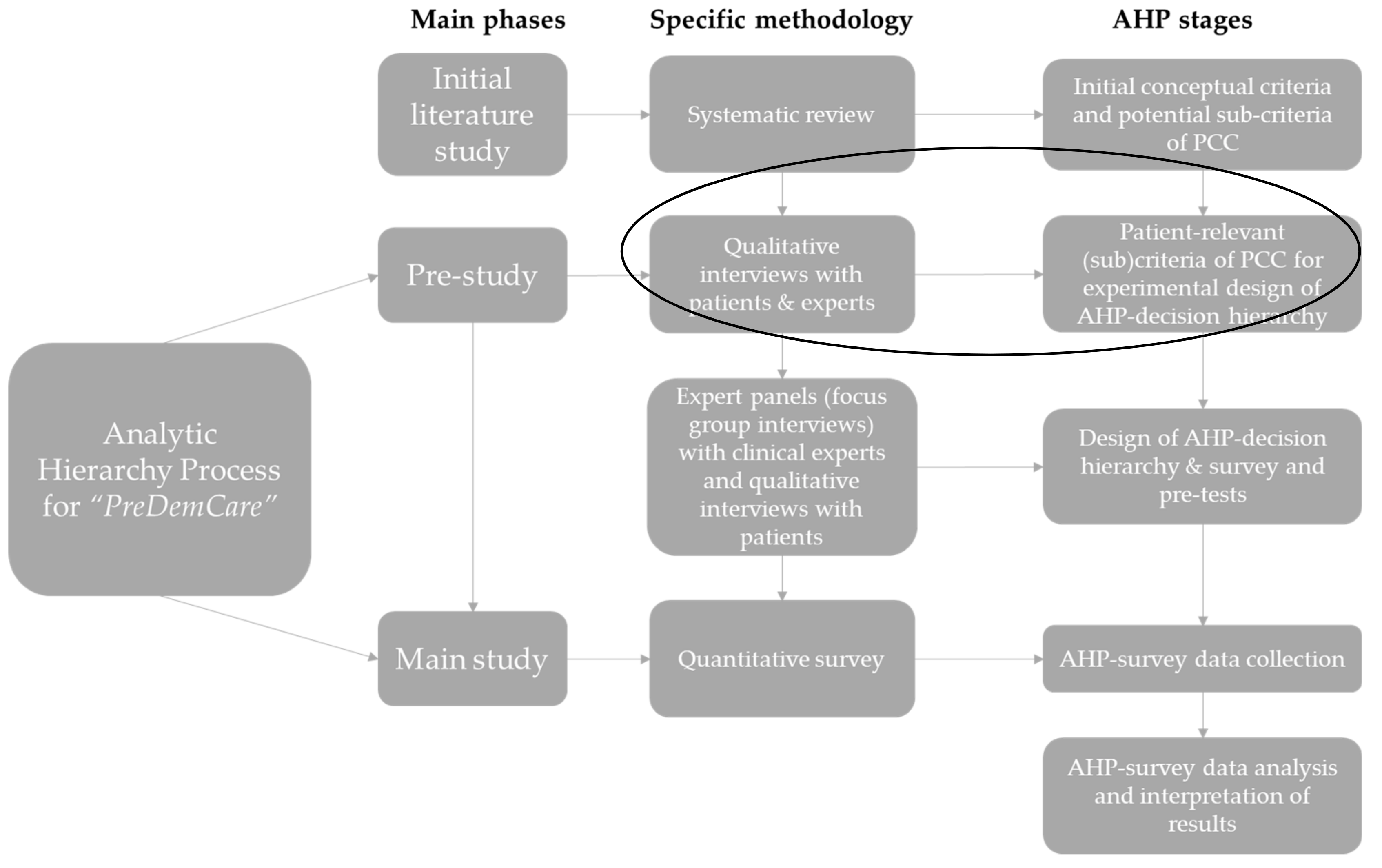

The overarching AHP-study, “PreDemCare” [33,34] adopts a sequential mixed-methods design for final instrument development [35], depicted in Figure 1. For the pre-study phase, we followed a qualitative design informed by a previous systematic review to identify relevant (sub)criteria, which would serve the development of an AHP. This report focuses exclusively on the pre-study phase of the overarching AHP study and describes the first qualitative component in detail.

Figure 1.

The mixed-methods design of the AHP for PreDemCare (own illustration inspired by [28]). Note: The initial literature study refers to a previously conducted systematic review [36]. AHP survey data will be analyzed with the principal right eigenvector method following Saaty [37]. Abbreviations: AHP = Analytic Hierarchy Process, PCC = person-centered care.

2.2.1. Theoretical Perspective

The theoretical perspective behind the overarching PreDemCare study, including this formative qualitative study, is guided by the theoretical foundations of the AHP, cf. Mühlbacher and Kaczynski [24]. The AHP is a method of prescriptive or normative decision theory, which provides the decision maker with techniques to reach a meaningful and plausible/rational decision [24,38]. The decision maker solves the decision problem based on predefined decision goal criteria and individual or group-specific priorities to identify the use-maximizing alternative systematically.

2.2.2. Initial Systematic Literature Review

The process of (sub)criteria identification [24] was based on a systematic review, which aimed to identify key intervention categories of PCC for PlwD. The results can be reviewed elsewhere [36]. Nine key components of PCC for PlwD were identified: Social contact, physical activities, cognitive training, sensory enhancement, daily living assistance, life history-oriented emotional support, training and support for professional caregivers, environmental adjustments, and care organization. Based on these findings from the literature, a comprehensive list of conceptual (sub)criteria was derived, depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conceptual criteria and potential sub-criteria oriented in systematic literature review [36].

The qualitative pre-study entailed (1) an expert panel with internal dementia-specific qualified nurses, so-called Dementia Care Managers (DCMs) [39] and (2) patient interviews with community-dwelling PlwD and informal caregivers (CGs) as silent supporters who live in diverse regions in rural German Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

2.3. Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

The authors WM and AR, public health scientists with qualitative research experience, conducted the interviews. AR has many years of quantitative patient preference research experience [24,40]. If one interviewer was hindered to participate, an experienced DCM from the site took over this role. Study nurses in ongoing clinical trials at the site (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT04741932, NCT01401582, German Clinical Trials Register Reference No.: DRKS00025074) functioned as gatekeepers to access the PlwD for patient interviews, as they may be perceived as trustworthy by the participants. None of the PlwD and informal CGs interviewed knew the scientists beforehand but were aware of their professional roles.

2.4. Sampling Strategy and Process

For the expert panel, two of the most experienced DCMs were selected at the site. PlwD for the patient interviews were selected by typical case sampling [41,42], a type of purposive sampling [43], from ongoing clinical trials at the site. The gatekeepers emphasized the independence of this study from the ongoing clinical trials. Informal CGs were invited to join as silent supporters.

2.5. Sampling Adequacy

For the determination of sampling adequacy in a formative qualitative study, such as ours, to support the development of a quantitative preference instrument, we oriented ourselves in recently published recommendations by Hollin et al. [29]. Following these, the focus should not be the number of subjects, which may differ from general qualitative research, but the strategical collection of actionable input for the development process. The latter includes the requirement of diversity in perspectives.

We addressed the diversity of perspectives by the inclusion of different stakeholders. Additionally, the initial overall sample size for the patient interviews n = 10 was informed by the expected saturation point [43] based on experiences from previous formative qualitative research for the development of quantitative preference instruments [67,68,69,70,71,72] and expected restricted access to PlwD due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The latter included ethical reflections in the study team to limit the risk associated with contact for both the vulnerable patient group and team members.

The identified (sub)criteria were subsequently revisited and assessed again during pre-tests of the to-be-developed AHP survey instrument in two expert panels with n = 4 DCMs, n = 4 physicians and n = 11 PlwD, cf. Figure 1. However, details on this subsequent stage in instrument development for the PreDemCare-study [34] lie outside the scope of this report.

2.6. Sample

The expert panel included n = 2 DCMs from the site’s staff. Patient interviews included n = 10 PlwD and n = 3 informal CGs (mainly as silent supporters).

2.7. Ethical Review

The overarching preference study PreDemCare, including this pre-study, was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee at the University Medicine Greifswald (Ref.-No.: BB018-21, BB018-21a, BB018-21b).

2.8. Data Collection Methods, Sources and Instruments

WM conducted the expert interview via video conference software. After translation to German, the DCMs reviewed the literature-derived conceptual criteria and their descriptions, as well as the sub-criteria, including respective icons for comprehensibility, and made suggestions for improvement. The expert interview was not recorded or transcribed. Data were collected with field notes. Changes were implemented immediately. The expert-reviewed material was prepared for the subsequent patient interviews.

Subsequently, individual narrative interviews [43] were conducted with PlwD in their homes or in day-care centers over the time period April–May 2021. All interviews were conducted in adherence to a strict hygiene protocol developed at the site during the COVID-19 pandemic. Method and setting were chosen to consider the vulnerability of this population appropriately. To ensure a comfortable and non-stressful interview situation, PlwD could invite their informal CGs to support them during interviews. It was, however, emphasized that the informal CGs should not act as proxies and answer the majority of the questions on behalf of the PlwD. WM conducted the interviews, while a second interviewer (AR or a DCM) took field notes. All interviews were recorded. All participants were informed about the purpose and content of the study, i.e., to obtain their opinion about relevant criteria of individualized homecare via the interview, including a card game, which would be used in research for the subsequent development of a survey. The interviewers explicitly stated that no tests would be performed. The audio tape was started after the introduction of the participants to ensure privacy. The average interview time was 60 min.

We used a self-developed semi-structured interview guide, oriented in Danner et al. [73], to ensure an efficient structure of the interview and simultaneously give the participants room to elaborate freely. Oriented in Danner et al. [25], we repeated after each pairwise comparison during the card games what the patient said with his/her judgement, e.g., “With your judgement you are saying that [Criterion X] is very much more important to you than [Criterion Y]; is this what you wanted to express?”, to make sure the information and tradeoffs presented during the card games were understood. We included an initial self-developed sociodemographic questionnaire for patient characteristics. Time since diagnosis and severity of cognitive impairment was determined during recruitment based on inclusion criteria (indication of MCI or early to moderate staged dementia) by the internal study nurses as gatekeepers based on their most recent assessment with a validated instrument in the respective clinical trial (Mini Mental Status Test (MMST)) [74] and/or Structured Interview for the Diagnosis of Dementia of the Alzheimer Type, multi-infarct dementia and dementias of other etiology according to DSM-III-R and ICD-10 score (SISCO) [75]).

The literature-based and expert-reviewed conceptual (sub)criteria were printed on cards in A5 format. Oriented in Danner et al. [73], criteria cards were presented to the PlwD as part of three card games to identify the most important and patient-relevant criteria of PCC. Card game 1 included sorting the criteria cards on three stacks (important, neutral, not important). Card game 2 included sorting the important criteria cards from card game 1 on two stacks (very important, less important). Results from the final ranking game, which included sorting the very important criteria cards from card game 2 in ranking order, were numbered according to their position awarded in this ranking. All results were documented with photographs and field notes. Blank cards were kept aside in case the PlwD mentioned additional criteria that had not been identified from the literature or in the expert interviews. Sub-criteria cards were only presented if there was time and energy left. If so, we asked about the appropriateness of the sub-criteria, their wording and the graphical design of included visual aids (ICONs).

By the described utilization of diverse data collection methods and different observers, we ensured both data and investigator triangulation [43].

2.9. Data Processing and Analysis

2.9.1. Card Games

Card game results were transferred into Microsoft®Excel2019 for a comprehensive overview. Ranking results were coded on a 10-point scale (rank 1 = 10 points, rank 2 = 9 points and so forth; excluded criteria were assigned zero points), whereupon sums and means for criteria across interviews were calculated.

2.9.2. Audio Recordings

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by WM. If names had been mentioned during the interview, these were not transcribed but replaced with, e.g., “XXX”, to ensure privacy. Two reviewers, WM and AA, coded transcripts line by line with qualitative content analysis [76,77,78] in Microsoft® Word2019. Oriented in Hshie & Shannon [78], we used elements from both conventional and directed qualitative content analysis, i.e., deductive analysis was guided by the interview guide and focused on information necessary to collect, cf. categories 1.–5. in Supplementary Material Codebook S1, but inductively other observations made were allowed to arise as additional categories from the transcripts, cf. category 6 in the Codebook S1. Concretely, each reviewer coded the first interview independently based on the interview guide and the conceptual criteria identified from the literature, cf. Table 1, but allowed for new categories to emerge. Subsequently, the reviewers discussed their codes and categories and agreed on a codebook. The codebook was revisited after independent coding of the second interview, and the strategy suggested was confirmed by both reviewers. Each reviewer coded the remaining interviews (n = 8) independently.

For categorization of the coded meaning units, coded transcripts from both reviewers were printed. Coded meaning units were discussed by both reviewers, cut out and assigned a tracker (interview number_lines in transcript). By this, we could trace back the distinct coded section and review it in its context, if necessary. Meaning units were hence sorted into the categories as given by the matrix from the Codebook S1.

Transcript and card game analyses were discussed in a final meeting between all authors until consensus on categorization was achieved. The finally categorized meaning units were transferred into digital format with Microsoft®Word2019.

3. Results

Patient characteristics are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (n = 10).

Six categories emerged from the analysis of the material: (1) patient-relevant criteria of PCC, (2) new criteria of PCC from the patient’s perspective, (3) plausible sub-criteria, (4) overlapping of criteria, (5) wording and comprehensibility and (6) other observations; (6a) reactions by patient, (6b) interaction with informal CG, (6c) explorative vs. ranking card game, (6d) setting and (6e) COVID-19.

3.1. Patient-Relevant Criteria

PlwD had preferences, and by use of the sorting and ranking card game, PlwD were able to express their preferences. Table 3 presents the list of criteria as identified after an analysis of the ranking card game. Six criteria were chosen for final inclusion in the AHP decision model and survey; social relationships, cognitive training, organization of health care, assistance with daily activities, characteristics of professional caregivers and physical activities.

Table 3.

Derivation of list of AHP criteria and plausible sub-criteria (ordered from most preferred to least per card game results).

3.2. New Criteria of PCC

All PlwD were asked whether we had missed criteria of PCC, which were important to them and not included in the criteria presented by us. No PlwD gave an indication of new criteria necessary to include, cf. Table 4. Hence, the literature-derived criteria were confirmed while reduced to a doable amount of criteria for the design of the AHP decision model and survey.

Table 4.

Results: Key quotations for categories 2, 4–6.

3.3. Plausible Sub-Criteria

Based on our observations during the patient interviews, where most participants got tired after ~60 min before we could show the sub-criteria cards, we decided that the AHP decision model and survey had to be kept as simple and short as possible. To limit the pairwise comparisons and to reduce the length and complexity of the planned survey, we decided to elicit and include only two sub-criteria per criterion in the AHP decision model, based on the PlwD’s initial elaborations about the presented criteria cards. Plausible sub-criteria are depicted in column four in Table 3.

3.4. Overlapping of Criteria

The participant’s elaborations about the cards gave indications about the potential overlap of criteria, cf. Table 4. Consequently, we decided to merge literature-derived criteria 1 (Social Activities) and 6 (Support with worries), as well as criteria 8 (Information for informal CGs) and 10 (Organization of care), cf. Table 1, which resulted in the criteria “social relationships” and “organization of health care”, cf. Table 3.

3.5. Wording and Comprehensibility

The participants had difficulties with the criteria’s general formulations, cf. Table 4. Once provided with concrete examples, the participants could relate well to the criteria. We decided to delete extensive criteria descriptions and instead described them with examples from the participant’s elaborations, cf. Table 3, column two.

Dementia is a sensitive topic. To prevent discontinuation of interviews, we had to adapt dementia-related terms in the interview guide and the card game. Consequently, the final (sub)criteria in Table 3 avoid dementia-related wording.

3.6. Other Observations

Several inductive observations emerged from data analysis, as presented in the following.

3.6.1. Reactions by PlwD

Initially, some participants were nervous, as some expected a test and wanted to “perform well”, despite explicit explanations by the interviewers that only their opinion was important to inform the subsequent development of a survey and no test would be performed. Some participants had difficulties dealing with “dementia” as a topic. During interviews with informal CGs or a DCM as a second interviewer present, some participants were “keen to please”.

3.6.2. Interaction with Informal CGs

During three interviews, informal CGs joined the PlwD. Some PlwD displayed concern about losing their informal CG, cf. Table 4. The relationship between PlwD and CG was at times affected by the better fitness of the CGs, who could be overstepping. During elaborations about help with, e.g., daily activities, particularly male PlwD showed expectations that their wife would take care of this.

3.6.3. Explorative vs. Card-Game Responses

Some PlwD had difficulties with the initial explorative part, which required abstract thinking to elaborate on the presented criteria and related experiences and wishes, cf. Table 4. The subsequent card game, which included concrete comparisons and sorting of the cards, did not pose a problem for the PlwD.

Many PlwD were still physically fit and did not need help with daily activities or adjustments to the living environment. Some elaborated “imagine if…” thoughts, i.e., if they would require help in the future would they be happy to receive it and how they would want to receive it. Others did not want to think about the unknown future and could not elaborate on what they would wish for their care, cf. Table 4.

3.6.4. Setting

The interviews were conducted in the German Federal State Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, a former part of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Elaborations about certain criteria, e.g., criterion 10, cf. Table 1 were associated with examples related to this setting. These examples from the past political and economic systems helped with the PlwDs’ understanding of the criteria, cf. Table 4. Consequently, we decided to include these examples (e.g., polyclinics in the GDR) to describe the patient relevant criteria and sub-criteria, cf. Table 3.

3.6.5. COVID-19

The PlwD’s elaborations were affected by COVID-19, cf. Table 4. Especially the criteria “access to social activities” and “physical activities” were mentioned as impacted by the COVID-19 restrictions.

4. Discussion

Our article contributes to the limited literature with a report on the systematic process of initial (sub)criteria derivation for the development of an AHP decision hierarchy and survey to elicit patient preferences for PCC among community-dwelling PlwD. This formative, qualitative research study was built on the previous identification of conceptual (sub)criteria by a systematic literature review. PlwD had preferences, and by use of the card game, they were able to express their preferences. The analysis resulted in six patient-relevant criteria, each with two sub-criteria; social relationships (indirect contact, direct contact), cognitive training (passive, active), organization of care (decentralized structures & no shared decision-making, centralized structures and shared decision making), assistance with daily activities (professional, family member), characteristics of professional CG (empathy, education and work experience) and physical activities (alone, group). No further criteria emerged from the interviews. Overlapping criteria were merged. The wording had to be substantially simplified by deletion of extensive criteria descriptions and replacement with concrete examples, and adjusted to dementia-sensitive language. Some PlwD initially were nervous to “perform well”, as they expected to be tested despite explicit explanations by the interviewers that this was not the case. COVID-19 was a present topic during the participants’ elaborations.

The initial systematic review allowed us to identify a preliminary broad set of possibly patient-relevant (sub)criteria. Key quotations presented in Table 3 give a clear indication that the selection of (sub)criteria was rooted in and supported by the voices of the decision makers. Furthermore, this qualitative pre-study gave us the opportunity to identify and exclude overlapping criteria in compliance with the credibility criteria of an AHP decision model [24].

Three of the identified six criteria—social relationships, cognitive training and assistance with daily activities—reflect attributes used in a previous quantitative, choice-based preference study with PlwD and their informal CGs [46]. We had oriented ourselves in Chester et al. [46] for the derivation of conceptual sub-criteria prior to the interviews, cf. Table 1. However, Chester et al. [46] applied another MCDA technique, a DCE, and included both PlwD and their informal CGs as respondents.

If we had relied only on results from the initial systematic review [36] and Chester et al. [46], the final list of (sub)criteria and the resulting number of pairwise comparisons would have become too extensive for this patient group. Furthermore, we would not have known if all identified criteria were relevant and important from the patient’s perspective. Hence, we tested if the criteria from the literature review were patient-relevant in terms of future decision making. This underlines the importance and necessity of conducting formative qualitative studies for contextual and population-specific appropriateness of the AHP (sub)criteria [24,26,27,30].

Despite explicit explanations by the interviewers, some PlwD were initially nervous to “perform well” as they expected a test. This reaction may be based on experiences with assessments for cognitive impairment in the clinical trials which we had recruited from. It may also be that the participants tried to hide their cognitive impairment due to the associated stigma with the diseases, as found by Xanthopoulou & McCabe [79], and hence wanted to perform well during the interview. Future quantitative preference research with PlwD may want to pay particular attention to avoiding expected or perceived test situations and preparation, respectively.

Corona (COVID-19) was a present topic during the participants’ elaborations, especially concerning access to social and physical activities. Lack of access to services and support due to COVID-19-related lockdowns has only recently been raised as a topic of great concern for this patient group [80,81]. It may be that the importance of criteria was affected by the COVID-19 measures, i.e., that the criteria’s relative importance was affected by current unmet needs. However, preferences are based on the processing of needs, values and goals and may shift as the social environment or contextual circumstances change [82]. It might also be that the COVID-19 measures simply enforced existing preferences for PCC criteria among PlwD. This phenomenon could be examined further by future research.

Even though potential clinical implications of our findings based on a small sample size are limited, the identified (sub)criteria of PCC serve the development of an AHP survey, which hence shall be used to elicit patient preferences for person-centered dementia care on a larger scale. Van Til and Ijzerman highlighted the advantage of quantitative preference elicitation methods for measurement of patient preferences on a larger and representative scale, which in turn would allow for reflection of the patient perspective in regulatory/health policy decisions [83]. As indicated by Mühlbacher [21], knowledge about most/least preferred health care options may help to increase acceptance and adherence to interventions among patients. Prioritization in the provision of those interventions accepted and preferred and avoidance of those options less preferred may reduce the financial pressure on health care systems [21]. This may affect both routine care and new concepts of care [40]. PCC requires knowledge about patient preferences [14,15,20,84]. Furthermore, Shared Decision Making between the health care provider and the patient is a core element of PCC [36,85]. PlwD as patients are “experts by experience”—hence, incorporation of their perspective in care decision making is of importance. Jayadevappa et al. [86], who applied a quantitative, choice-based preference instrument, saw i.a. improved satisfaction with care and decision, as well as reduced regrets. Quantitative preference elicitation instruments, such as the AHP, may form a powerful instrument for consideration of the patient perspective in dementia care decision making on a larger scale [83]. However, the validity of quantitative, criteria-based preference elicitation instruments depends on appropriate identification of the included criteria to reduce the risk of bias and inaccurate results [24,26,27,28]. The latter can be reduced by a rigorous, systematic and transparently reported identification of (sub)criteria [28,29], as in this current study, which provides initial data of patient-relevant (sub)criteria for the design of an AHP decision hierarchy and survey for person-centered dementia care.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Conceptual (sub)criteria identified from literature had to be translated from English to German. Information could have been lost in translation or content compromised by language errors. However, the translation by WM was reviewed by the other authors, as well as by the DCMs during the expert panel, which mitigated the probability of possible translation flaws. The expert panel included a small number of participants (n = 2), who were internal colleagues of members of the study team. However, expert perspectives were not the primary objective of this pre-study. Consultation with clinical experts can, nonetheless, provide the basis for identifying the full set of (sub)criteria for subsequent qualitative research with patients and is in accordance with good research practices in patient preference research [87]. Similar to our study, Kløjgaard et al. [88] only included n = 2 experts in the formative qualitative study phase for the development of the quantitative preference instrument. Compared to usual sample sizes in general qualitative research, the number of participants during the patient interviews may appear low. As aforementioned, cf. Section 2.5, we oriented ourselves in a recent publication by Hollin et al. [29], which entailed guidelines for formative qualitative research, such as ours, to support the development of quantitative preference instruments. The authors emphasize that sampling in these study phases should not focus on the number of units but on collecting actionable input for the development process, which needs a diversity of perspectives. They underline that sampling adequacy in formative qualitative research may entail smaller samples than in general qualitative work, which given the limited study purpose, may be adequate [29]. To complement suggestions by Hollin et al. [29] and inform the expected saturation point as guidance for sample size determination, we oriented ourselves in previous quantitative patient preference research, including works by second author AR, which report similar sample sizes in the formative pre-study phase(s) [67,68,69,70,71,72]. In this formative qualitative study, saturation started to appear from patient interview number six. The remaining four interviews clarified and consolidated the ranking of criteria, especially of “social relationships”, “cognitive training”, and “physical activities”. By the inclusion of several stakeholders, we ensured a diversity of perspectives. We could have conducted focus group interviews with the PlwD as Danner et al. [73]. However, due to the sensitivity of the topic, the vulnerability of the patient group, and COVID-19-related restrictions on group meetings, we refrained from this option. Another option might have been to administer the card game as an online patient survey for the identification of patient-relevant (sub)criteria [24], by which risks associated with contact during the COVID-19 pandemic would have been limited, and the sample size potentially could have been increased. However, an online patient survey without interviewer assistance with this particular patient group—aged adults with cognitive impairments, oftentimes living in rural areas, which may have limited access to the internet and a lack of necessary digital literacy [89]—was deemed not feasible by the study team based on previous research [25] and experiences from other projects at the site [90]. As criteria-related questions and card games took longer than expected and most PlwD got tired, we could not show the sub-criteria cards and ask for feedback on their appropriateness and comprehensibility. Instead, we elicited plausible sub-criteria from the participants’ initial elaborations about the criteria cards, which, together with the designed ICONs, were planned to be tested for their appropriateness during the subsequent pretests of the AHP survey, cf. Figure 1. Generally, interviewers should not guide interviewees and rather aim for open interview questions [91]. This requirement was difficult to fulfill with this patient group and research aim. PlwD had difficulties with open/abstract questions and needed guidance throughout the interviews with concrete questions to create a comfortable interview situation, as observed in previous research [92]. Future patient preference research with a cognitively impaired population may want to consider these observations. For some PlwD, elaborations about selected criteria required imagination of potential scenarios in the future. This resulted in some inconsistency between the explorative part and card games, which could be an early indication of a known methodological problem with the AHP. Thus, the AHP is criticized for the mere pairwise comparisons not fully reflecting to a real decision-making situation, as the decision maker never is confronted with the entirety of a decision problem but only with individual aspects of an overall decision [93]. It could also be an indicator that the cognitively impaired patient group did not understand the information and tradeoffs presented during the card games. However, we followed the same approach as Danner et al. [25], i.e., to repeat after each pairwise comparison during the card games what the patient said with his/her judgement, to counteract this potential problem. Per our observations, cf. Section 3.1 and Section 3.6.3, the patients understood the information and tradeoffs presented during the card games well, compared to the more explorative part at the beginning of the interviews. Hence, we are confident in the results of the presented tradeoffs. As we remained compliant with our research focus and collected a manageable amount of data in a short period of time, the requirements for credibility and dependability with regard to the study’s trustworthiness were viewed as fulfilled [94]. Transferability of findings is limited due to the aforementioned rather small sample sizes of included subjects, the specificities of our setting and related cultural differences. Nevertheless, due to the rigor of the methodological process and reporting, we consider our findings trustworthy.

5. Conclusions

This formative qualitative study complements the limited literature with initial data about patient-relevant criteria of PCC for PlwD to design a quantitative preference instrument. To the best of our knowledge, our research is among the first to provide insight into the methodological processes of (sub)criteria development for the subsequent design of an AHP for a cognitively impaired population. PlwD had preferences and, by use of the card game, were able to express their preferences. The transferability of our findings is limited due to the comparatively small sample sizes of included subjects. Aside from the consideration of larger sample sizes, future research should pay particular attention (a) to clarify the purpose of the study and to ensure tradeoffs are understood by the participants, (b) to include simple and concrete rather than abstract as well as dementia-sensitive wording and (c) to account for the energy required in relation to the age and cognitive status of the participants, as well as challenges in qualitative research with this population, which requires great researcher flexibility. A consideration of our observations in future quantitative preference research with PlwD may help to increase the confidence in such research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19137629/s1, Supplemental Codebook S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M., A.R., B.M., W.H.; methodology, W.M., A.R., B.M., W.H.; software, N/A; validation, W.M., A.R., B.M., W.H.; formal analysis, W.M., A.R., A.A., F.M., M.P., B.M.; investigation, W.M., A.R., resources, W.M., A.R., A.A.; data curation, W.M., A.R., A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.; writing—review and editing, A.R., A.A., F.M., M.P., B.M., W.H.; visualization, W.M.; supervision, A.R., W.H.; project administration, W.M., A.R.; funding acquisition, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author, W.M., is funded by the Hans and Ilse Breuer Foundation under the Alzheimer Doctoral Scholarship, review at: https://www.breuerstiftung.de/en/projekte/promotionsstipendien/ (accessed on 16 June 2022). Grant number: N/A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) at the University Medicine Greifswald (Approval No.: BB018-21, BB018-21a, BB018-21b).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data and methods used are presented in sufficient detail in the paper so that other researcher can replicate the work. Raw data will not be made publicly available to protect patient confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Peer Reviewers and the Editor(s) for their valuable inputs, which helped us to improve the quality of this paper. We thank all participants for their contribution to this study. Additionally, we would like to thank Ulrike Kempe, Sebastian Lange and Mandy Freimark, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases e.V. (DZNE) Site Rostock/Greifswald, to support with patient recruitment as gatekeepers to the informants. Furthermore, we would like to thank Pablo Collantes Jiménez, Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology Greifswald, for helping with the graphical design of the sub-criteria icons. The first author, WM, would like to thank the Hans and Ilse Breuer Foundation for their financial support of this study with the ‘Alzheimer’s Doctoral Scholarship’.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Prince, M.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Knapp, M.; Guerchet, M.; Karagiannidou, M. World Alzheimer Report 2016—Improving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia: Coverage, Quality and Costs Now and in the Future; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dementia Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Bryce, R.; Ferri, C. World Alzheimer Report 2011—The Benefits of Early Diagnosis and Intervention; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Dementia Care Practice Recommendations. Available online: https://www.alz.org/professionals/professional-providers/dementia_care_practice_recommendations (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers (NG97). NICE Guideline; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Nationella Riktlinjer för Vård Och Omsorg Vid Demenssjukdom. Stöd för Styrning Och Ledning; The National Board of Health and Welfare Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

- NHMRC Partnership Centre for Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia; NHMRC Partnership Centre for Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dely, H.; Verschraegen, J.; Setyaert, J. You and Me, Together We Are Human—A Reference Framework for Quality of Life, Housing and Care for People with Dementia; Flanders Centre of Expertise on Dementia: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan, E.; Bopp-Kistler, I.; Buerge, M.; Fischlin, R.; Georgescu, D.; Giardini, U.; Hatzinger, M.; Hemmeter, U.; Justiniano, I.; Kressig, R.W.; et al. Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Behavioralen und Psychologischen Symptome der Demenz (BPSD). Praxis 2014, 103, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danish Health Authority. Forebyggelse og Behandling af Adfærdsmæssige og Psykiske Symptomer hos Personer Med Demens. National Klinisk Retningslinje; Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Dementia Plan 2020—A More Dementia-Friendly Society; Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway, 2015.

- Morgan, S.; Yoder, L. A concept analysis of person-centered care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2012, 30, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T.; Bredin, K. Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing Soc. 1992, 12, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First (Rethinking Ageing Series); Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lepper, S.; Rädke, A.; Wehrmann, H.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Preferences of Cognitively Impaired Patients and Patients Living with Dementia: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Patient Preference Studies. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, H.; Michalowsky, B.; Lepper, S.; Mohr, W.; Raedke, A.; Hoffmann, W. Priorities and Preferences of People Living with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment—A Systematic Review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 2793–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.H.; Chang, H.R.; Liu, M.F.; Chien, H.W.; Tang, L.Y.; Chan, S.Y.; Liu, S.H.; John, S.; Traynor, V. Decision-Making in People With Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Narrative Review of Decision-Making Tools. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2056–2062.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison Dening, K.; King, M.; Jones, L.; Vickerstaff, V.; Sampson, E.L. Correction: Advance Care Planning in Dementia: Do Family Carers Know the Treatment Preferences of People with Early Dementia? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Haitsma, K.; Curyto, K.; Spector, A.; Towsley, G.; Kleban, M.; Carpenter, B.; Ruckdeschel, K.; Feldman, P.H.; Koren, M.J. The preferences for everyday living inventory: Scale development and description of psychosocial preferences responses in community-dwelling elders. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A. Ohne Patientenpräferenzen kein sinnvoller Wettbewerb. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2017, 114, A 1584–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewoud, S.; Van Exel, N.J.A.; Bobinac, A.; Berg, M.; Huijsman, R.; Stolk, E.A. What influences patients’ decisions when choosing a health care provider? Measuring preferences of patients with knee arthrosis, chronic depression, or Alzheimer’s disease, using discrete choice experiments. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 1941–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A.; Zweifel, P.; Johnson, F.R. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: An overview. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A. Der Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): Eine Methode zur Entscheidungsunterstützung im Gesundheitswesen. Pharm. Ger. Res. Artic. 2013, 11, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danner, M.; Vennedey, V.; Hiligsmann, M.; Fauser, S.; Gross, C.; Stock, S. How Well Can Analytic Hierarchy Process be Used to Elicit Individual Preferences? Insights from a Survey in Patients Suffering from Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Patient 2016, 9, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thokala, P.; Devlin, N.; Marsh, K.; Baltussen, R.; Boysen, M.; Kalo, Z.; Longrenn, T.; Mussen, F.; Peacock, S.; Watkins, J. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis for Health Care Decision Making—An Introduction: Report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsh, K.; IJzerman, M.; Thokala, P.; Baltussen, R.; Boysen, M.; Kaló, Z.; Lönngren, T.; Mussen, F.; Peacock, S.; Watkins, J. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis for Health Care Decision Making—Emerging Good Practices: Report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016, 19, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abiiro, G.A.; Leppert, G.; Mbera, G.B.; Robyn, P.J.; De Allegri, M. Developing attributes and attribute-levels for a discrete choice experiment on micro health insurance in rural Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollin, I.L.; Craig, B.M.; Coast, J.; Beusterien, K.; Vass, C.; DiSantostefano, R.; Peay, H. Reporting formative qualitative research to support the development of quantitative preference study protocols and corresponding survey instruments: Guidelines for authors and reviewers. Patient-Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2020, 13, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coast, J.; Al-Janabi, H.; Sutton, E.J.; Horrocks, S.A.; Vosper, A.J.; Swancutt, D.R.; Flynn, T.N. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: Issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases e.V. (DZNE). PreDemCare: Moving towards Person-Centered Care of People with Dementia—Elicitation of Patient and Physician Preferences for Care. Available online: https://www.dzne.de/en/research/studies/projects/predemcare/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Rädke, A.; Mohr, W.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. POSA422 Preferences for Person-Centred Care Among People with Dementia in Comparison to Physician’s Judgments: Study Protocol for the Predemcare Study. Value Health 2022, 25, S272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, W.; Rädke, A.; Afi, A.; Edvardsson, D.; Mühlichen, F.; Platen, M.; Roes, M.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Key Intervention Categories to Provide Person-Centered Dementia Care: A Systematic Review of Person-Centered Interventions. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2021, 84, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision-making with the AHP: Why is the principal eigenvector necessary. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 145, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, L. Methoden der Präferenzmessung: Grundlagen, Konzepte und Experimentelle Untersuchungen; Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, T.; Thyrian, J.R.; Dreier, A.; Wucherer, D.; Köhler, L.; Fiß, T.; Böwing, G.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Dementia care management: Going new ways in ambulant dementia care within a GP-based randomized controlled intervention trial. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A. Making good decisions in healthcare with multi-criteria decision analysis: The use, current research and future development of MCDA. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2016, 14, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruoglu, E.; Guldal, D.; Mevsim, V.; Gunvar, T. Which family physician should I choose? The analytic hierarchy process approach for ranking of criteria in the selection of a family physician. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, M.; Mabry, L. RealWorld Evaluation: Working under Budget, Time, Data, and Political Constraints; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, K.; Lafortune, L.; Kavanagh, J.; Thomas, J.; Mays, N.; Erens, B. Non-Drug Treatments for Symptoms in Dementia: An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Non-Pharmacological Interventions in the Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Challenging Behaviours in Patients with Dementia; The Policy Research Unit in Policy Innovation Research (PIRU): London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, P.; Hughes, J.; Xie, C.; Larbey, M.; Roe, B.; Giebel, C.M.; Jolley, D.; Challis, D.; Group, H.D.P.M. Overview of systematic reviews: Effective home support in dementia care, components and impacts—Stage 1, psychosocial interventions for dementia. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2845–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, H.; Clarkson, P.; Davies, L.; Sutcliffe, C.; Davies, S.; Feast, A.; Hughes, J.; Challis, D.; Members of the HOST-D (Home Support in Dementia) Programme Management Group. People with dementia and carer preferences for home support services in early-stage dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Orrell, M.; Williams, G.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Romeo, R.; Woods, B.; Garrod, L.; Testad, I.; Woodward-Carlton, B. Impact of person-centred care training and person-centred activities on quality of life, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in nursing homes: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P.; van Weert, J.C.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; van Meijel, B.; Dröes, R.-M. Testing the implementation of the Veder Contact Method: A theatre-based communication method in dementia care. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Thein, K.; Marx, M.S.; Dakheel-Ali, M.; Freedman, L. Efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions for agitation in advanced dementia: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossey, J.; Ballard, C.; Juszczak, E.; James, I.; Alder, N.; Jacoby, R.; Howard, R. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: Cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawton, M.P.; Van Haitsma, K.; Klapper, J.; Kleban, M.H.; Katz, I.R.; Corn, J. A stimulation-retreat special care unit for elders with dementing illness. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1998, 10, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, F.H.E.; Thompson, C.L.; Nieh, C.M.; Nieh, C.C.; Koh, H.M.; Tan, J.J.C.; Yap, P.L.K. Person-centered care for older people with dementia in the acute hospital. Alzheimer Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, E.S.; Eppingstall, B.; Camp, C.J.; Runci, S.J.; Taffe, J.; O’Connor, D.W. A randomized crossover trial to study the effect of personalized, one-to-one interaction using Montessori-based activities on agitation, affect, and engagement in nursing home residents with Dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haitsma, K.S.; Curyto, K.; Abbott, K.M.; Towsley, G.L.; Spector, A.; Kleban, M. A randomized controlled trial for an individualized positive psychosocial intervention for the affective and behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; van Rossum, E.; Ambergen, T.; Kempen, G.I.; Hamers, J.P. Effects of small-scale, home-like facilities in dementia care on residents’ behavior, and use of physical restraints and psychotropic drugs: A quasi-experimental study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weert, J.C.; van Dulmen, A.M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.M.; Ribbe, M.W.; Bensing, J.M. Effects of snoezelen, integrated in 24 h dementia care, on nurse–patient communication during morning care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 58, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sloane, P.D.; Hoeffer, B.; Mitchell, C.M.; McKenzie, D.A.; Barrick, A.L.; Rader, J.; Stewart, B.J.; Talerico, K.A.; Rasin, J.H.; Zink, R.C. Effect of person-centered showering and the towel bath on bathing-associated aggression, agitation, and discomfort in nursing home residents with dementia: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; King, M.T.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Brodaty, H.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Norman, R.; Haas, M.; Luscombe, G. Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eritz, H.; Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Williams, J.; Kroeker, K.; Martin, R.R.; Lix, L.M.; Hunter, P.V. A life history intervention for individuals with dementia: A randomised controlled trial examining nursing staff empathy, perceived patient personhood and aggressive behaviours. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokstad, A.M.M.; Røsvik, J.; Kirkevold, Ø.; Selbaek, G.; Benth, J.S.; Engedal, K. The effect of person-centred dementia care to prevent agitation and other neuropsychiatric symptoms and enhance quality of life in nursing home patients: A 10-month randomized controlled trial. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2013, 36, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testad, I.; Mekki, T.E.; Førland, O.; Øye, C.; Tveit, E.M.; Jacobsen, F.; Kirkevold, Ø. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)—training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Tolson, D.; Eerlingen, R.; Carvers, D.; Wouters, K.; Paque, K.; Timmermans, O.; Dilles, T.; Engelborghs, S. SolCos model-based individual reminiscence for older adults with mild to moderate dementia in nursing homes: A randomized controlled intervention study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 23, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; Forbes, I.; Fleming, R.; King, M.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Luscombe, G.; Kenny, P.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Haas, M.; Brodaty, H. PerCEN: A cluster randomized controlled trial of person-centered residential care and environment for people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, G.; Draskovic, I.; Adang, E.M.; Donders, R.; Zuidema, S.U.; Koopmans, R.T.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.J. Effects of dementia-care mapping on residents and staff of care homes: A pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villar, F.; Celdrán, M.; Vila-Miravent, J.; Fernández, E. Involving institutionalized people with dementia in their care-planning meetings: Impact on their quality of life measured by a proxy method: Innovative Practice. Dementia 2019, 18, 1936–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.F.; Sculpher, M.J.; Claxton, K.; Stoddart, G.L.; Torrance, G.W. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Rudolph, I.; Lincke, H.-J.; Nübling, M. Preferences for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Bethge, S. Patients’ preferences: A discrete-choice experiment for treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2015, 16, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A.; Dippel, F.-W.; Bethge, S. Patient priorities for treatment attributes in adjunctive drug therapy of severe hypercholesterolemia in germany: An analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2018, 34, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.; Bethge, S.; Kaczynski, A.; Juhnke, C. Objective criteria in the medicinal therapy for type II diabetes: An analysis of the patients’ perspective with analytic hierarchy process and best-worst scaling. Gesundh. (Bundesverb. Der Arzte Des. Offentlichen Gesundh.) 2015, 78, 326. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A. The expert perspective in treatment of functional gastrointestinal conditions: A multi-criteria decision analysis using AHP and BWS. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2016, 23, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weernink, M.G.; van Til, J.A.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.; IJzerman, M.J. Patient and public preferences for treatment attributes in Parkinson’s disease. Patient-Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2017, 10, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danner, M.; Vennedey, V.; Hiligsmann, M.; Fauser, S.; Stock, S. Focus Groups in Elderly Ophthalmologic Patients: Setting the Stage for Quantitative Preference Elicitation. Patient 2016, 9, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaudig, M.; Mittelhammer, J.; Hiller, W.; Pauls, A.; Thora, C.; Morinigo, A.; Mombour, W. SIDAM—A structured interview for the diagnosis of dementia of the Alzheimer type, multi-infarct dementia and dementias of other aetiology according to ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. Psychol. Med. 1991, 21, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 23 February 2014).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/%20fqs/article/view/1089/2385 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P.; McCabe, R. Subjective experiences of cognitive decline and receiving a diagnosis of dementia: Qualitative interviews with people recently diagnosed in memory clinics in the UK. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bacsu, J.R.; O’Connell, M.E.; Webster, C.; Poole, L.; Wighton, M.B.; Sivananthan, S. A scoping review of COVID-19 experiences of people living with dementia. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W.; Bohlken, J.; Kostev, K. Effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on disease recognition and utilisation of healthcare services in the older population in Germany: A cross-sectional study. Age Ageing 2020, 50, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haitsma, K.; Abbott, K.M.; Arbogast, A.; Bangerter, L.R.; Heid, A.R.; Behrens, L.L.; Madrigal, C. A Preference-Based Model of Care: An Integrative Theoretical Model of the Role of Preferences in Person-Centered Care. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Til, J.A.; Ijzerman, M.J. Why Should Regulators Consider Using Patient Preferences in Benefit-risk Assessment? PharmacoEconomics 2014, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edvardsson, D.; Varrailhon, P.; Edvardsson, K. Promoting person-centeredness in long-term care: An exploratory study. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 40, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fazio, S.; Pace, D.; Flinner, J.; Kallmyer, B. The Fundamentals of Person-Centered Care for Individuals With Dementia. Gerontologist 2018, 58, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jayadevappa, R.; Chhatre, S.; Gallo, J.J.; Wittink, M.; Morales, K.H.; Lee, D.I.; Guzzo, T.J.; Vapiwala, N.; Wong, Y.-N.; Newman, D.K. Patient-centered preference assessment to improve satisfaction with care among patients with localized prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, J.F.P.; Hauber, A.B.; Marshall, D.; Lloyd, A.; Prosser, L.A.; Regier, D.A.; Johnson, F.R.; Mauskopf, J. Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health—a Checklist: A Report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011, 14, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kløjgaard, M.E.; Bech, M.; Søgaard, R. Designing a stated choice experiment: The value of a qualitative process. J. Choice Model. 2012, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hannemann, N.; Götz, N.-A.; Schmidt, L.; Hübner, U.; Babitsch, B. Patient connectivity with healthcare professionals and health insurer using digital health technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A German cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyrian, J.R.; Fiß, T.; Dreier, A.; Böwing, G.; Angelow, A.; Lueke, S.; Teipel, S.; Fleßa, S.; Grabe, H.J.; Freyberger, H.J. Life-and person-centred help in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany (DelpHi): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2012, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Given, L.M. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beuscher, L.; Grando, V.T. Challenges in conducting qualitative research with individuals with dementia. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neidhardt, K.; Wasmuth, T. Die Gewichtung Multipler Patientenrelevanter Endpunkte—Ein Methodischer Vergleich von Conjoint Analyse und Analytic Hierarchy Process unter Berücksichtigung des Effizienzgrenzenkonzepts des IQWIG; Diskussionspapier 02-12; Rechts- und Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät, Universität Bayreuth: Bayreuth, Germany, 2012; ISSN 1611-3837. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).