Keeping the Agenda Current: Evolution of Australian Lived Experience Mental Health Research Priorities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Ethics and Consent Processes

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Delivery Mode and Tools

2.3.2. World Café Method

2.4. Questions

- What are the main issues you see as important in mental health in Australia?Prompts: What are the issues or problems that are important to you or the people you support? Are there any potential ways that these issues could be improved for you, or for the people you support?

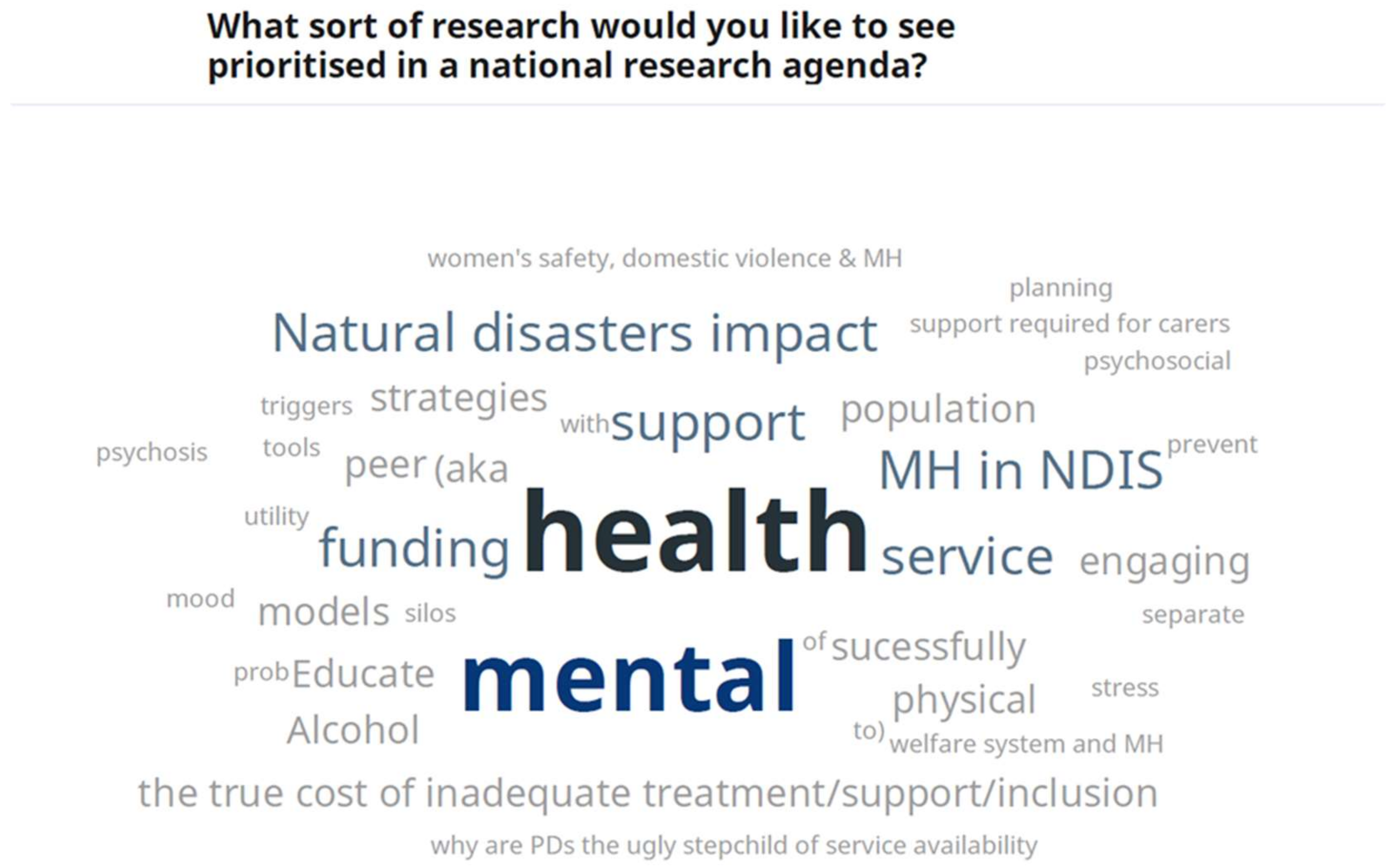

- What sort of research would you like to see prioritised in a national research agenda?Prompts: What things do the government or other agencies need to know more about so they can better address your and your family’s needs? Is there a specific program, service, or treatment that you think should be evaluated? Is there a particular illness or group that we should focus on?

- How do you currently engage with research?Prompts: What features of the research do you think make it useful to you or others? How do you find out about participating in mental health research? How would you like to be informed about how to help with being involved in conducting research? How would you like to engage with research in the future?

2.5. Ranking of Priorities

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Current Study Results

3.1.1. Main Issues for Mental Health in Australia

3.1.2. Priorities for Research in a National Agenda

3.2. Comparison with Previous Priority-Setting

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banfield, M.A.; Barney, L.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H.M. Australian mental health consumers’ priorities for research: Qualitative findings from the SCOPE for Research project. Health Expect. 2014, 17, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caldon, L.J.M.; Marshall-Cork, H.; Speed, G.; Reed, M.W.R.; Collins, K. Consumers as researchers—Innovative experiences in UK National Health Service Research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, Z.S.; Wooding, S.; Grant, J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. J. R. Soc. Med. 2011, 104, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robotham, D.; Wykes, T.; Rose, D.; Doughty, L.; Strange, S.; Neale, J.; Hotopf, M. Service user and carer priorities in a Biomedical Research Centre for mental health. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zurynski, Y.; Smith, C.L.; Knaggs, G.; Meulenbroeks, I.; Braithwaite, J. Funding research translation: How we got here and what to do next. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2021, 45, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfield, M.A.; Morse, A.R.; Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M. Mental health research priorities in Australia: A consumer and carer agenda. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfeddali, I.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; van Os, J.; Knappe, S.; Vieta, E.; Wittchen, H.U.; Obradors-Tarrago, C.; Haro, J.M. Horizon 2020 Priorities in Clinical Mental Health Research: Results of a Consensus-Based ROAMER Expert Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 10915–10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiorillo, A.; Luciano, M.; Del Vecchio, V.; Sampogna, G.; Obradors-Tarrago, C.; Maj, M.; Consortium, R. Priorities for mental health research in Europe: A survey among national stakeholders’ associations within the ROAMER project. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forsman, A.K.; Wahlbeck, K.; Aaro, L.E.; Alonso, J.; Barry, M.M.; Brunn, M.; Cardoso, G.; Cattan, M.; de Girolamo, G.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; et al. Research priorities for public mental health in Europe: Recommendations of the ROAMER project. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breault, L.J.; Rittenbach, K.; Hartle, K.; Babins-Wagner, R.; de Beaudrap, C.; Jasaui, Y.; Ardell, E.; Purdon, S.E.; Michael, A.; Sullivan, G.; et al. People with lived experience (PWLE) of depression: Describing and reflecting on an explicit patient engagement process within depression research priority setting in Alberta, Canada. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2018, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollis, C.; Sampson, S.; Simons, L.; Davies, E.B.; Churchill, R.; Betton, V.; Butler, D.; Chapman, K.; Easton, K.; Gronlund, T.A.; et al. Identifying research priorities for digital technology in mental health care: Results of the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, N.; McVey, G.; Seale, E.; Preskow, W.; Norris, M.L. Cocreating research priorities for anorexia nervosa: The Canadian Eating Disorder Priority Setting Partnership. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldiss, S.; Fern, L.A.; Phillips, R.S.; Callaghan, A.; Dyker, K.; Gravestock, H.; Groszmann, M.; Hamrang, L.; Hough, R.; McGeachy, D.; et al. Research priorities for young people with cancer: A UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banfield, M.A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H.M.; Barney, L.J. Scope for research: Mental health consumers’ priorities for research compared with recent research in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2011, 45, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfield, M.; Randall, R.; O’Brien, M.; Hope, S.; Gulliver, A.; Forbes, O.; Morse, A.R.; Griffiths, K. Lived experience researchers partnering with consumers and carers to improve mental health research: Reflections from an Australian initiative. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banfield, M.; Gulliver, A.; Morse, A.R. Virtual World Café Method for Identifying Mental Health Research Priorities: Methodological Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, A.R.; Forbes, O.; Jones, B.A.; Gulliver, A.; Banfield, M. Australian Mental Health Consumer and Carer Perspectives on Ethics in Adult Mental Health Research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2019, 14, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). Australian Research Council and Universities Australia; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, S.; Ling, J.; Mosoiu, D.; Arantzamendi, M.; Tserkezoglou, A.J.; Predoiu, O.; Payne, S. Undertaking Research Using Online Nominal Group Technique: Lessons from an International Study (RESPACC). J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1867–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. The World Café: Shaping Our Futures through Conversations That Matter; Berrett-Koehler: San Franciso, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Brown, J. The World Café in Singapore: Creating a Learning Culture through Dialogue. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2005, 41, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondo, P.D.; King, S.; Minhas, B.; Fassbender, K.; Simon, J.E.; On behalf of the Advance Care Planning Collaborative Research; Innovation Opportunities Program. How to increase public participation in advance care planning: Findings from a World Café to elicit community group perspectives. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKimm, J.; Ramani, S.; Kusurkar, R.A.; Fornari, A.; Nadarajah, V.D.; Thampy, H.; Filipe, H.P.; Kachur, E.K.; Hays, R. Capturing the wisdom of the crowd: Health professions’ educators meet at a virtual world café. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2020, 9, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teherani, A.; Martimianakis, T.; Stenfors-Hayes, T.; Wadhwa, A.; Varpio, L. Choosing a Qualitative Research Approach. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2015, 7, 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buckmaster, L.; Clark, S. The National Disability Insurance Scheme: A Chronology; Parlimentary Library: Canberra, Australia, 13 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, D.E.; Iqbal, A.; Faehrmann, L.; Tadić, I.; Paulino, E.; Chen, T.F.; Moullin, J.C. Using an online nominal group technique to determine key implementation factors for COVID-19 vaccination programmes in community pharmacies. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 1705–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Themes and Subthemes |

|---|

| Service and system issues |

| Accessibility, e.g., community supports, costs |

| Acute care, lack of beds |

| Alternatives to hospital, availability of appropriate services |

| Alternatives to psychiatry, holistic treatment |

| Awareness of services |

| Diagnostic overshadowing |

| Evaluation of programs |

| Falling through cracks |

| Implementation of plans, services, inquiries |

| Lack of funding, esp recurrent, short programs |

| Least restrictive practice |

| * Measurement issues |

| Missing middle |

| Psych support in prisons, forensic services, alternatives |

| Public private split |

| Rural and remote mental health, services |

| Staffing capacity and capability |

| Trauma-informed care |

| * Welfare and housing |

| Policy and political impact |

| Funding relative to physical health |

| Cost shifting Federal/State |

| * Costs to the individual |

| Police and MH services |

| * Justice system |

| Psychosocial disability |

| Balance of illness and independence |

| Disability sector vs MH sector |

| Functional ability |

| NDIS—episodic care, independent assessments, peer services |

| Psychosocial assessment |

| Psychosocial disability left out |

| Inclusion and supports |

| Normalising workplace reasonable adjustment |

| Seeking work, homelessness |

| Social inclusion, reintegration |

| Supported accommodation |

| Carers |

| Carer peer support |

| Carer roles and impacts, families |

| Causes and risk factors |

| * Ageing |

| Disasters |

| * Brain research |

| * Domestic violence |

| Social media |

| Disorder specific |

| Best practice personality disorders |

| Dual diagnosis |

| Eating disorders |

| Neurodiversity and MH |

| * Psychosis, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder |

| Prevention and early intervention |

| Early intervention |

| Mental health in schools |

| Resilience |

| Youth supports, prevention |

| Suicide prevention |

| Specific populations |

| Multicultural support |

| LGBTIQ+ identity, access and inclusion |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders |

| Lived experience involvement |

| * Involvement in quantitative research |

| Lived experience in policymaking |

| Consumer rights |

| Treatments and other interventions |

| Optimising medications |

| Physical activity |

| * Specific treatments, e.g., EMDR |

| Peer workforce issues |

| Peer support and workforce |

| Peer support in industry (e.g., mates in construction) |

| Stigma, discrimination and associated behaviours |

| Perceptions of mental health as separate to health |

| Recovery |

| Highest | Lowest |

|---|---|

| Better access to community support when needed | Co-designing information about medications |

| Creative ways to increase funding to increase research and services | COVID |

| dementia and older people | Forget reducing Stigma and look at addressing behaviour emanating from that attitude |

| * greater peer support evidence base | government funding |

| How to educate the population in (trying to) prevent Mental Illness | * greater peer support evidence base |

| medical research negative symptoms of schizophrenia | perceptions of ‘mental’ health |

| missing middle | Personality disorder best practice |

| more holistic/‘whole-of-person’ treatment | social media—increasing anxiety |

| reasonable adjustments—what are they, who decides, seeing more | stigma |

| Re-integration into community | TMS available in multiple areas and regional |

| why are PDs the ugly stepchild of service availability | -- |

| Thematic Areas from Current Research | Thematic Areas from Banfield et al. [6]. |

|---|---|

| Service and system issues | Services |

| Psychosocial disability | National Disability Insurance Scheme |

| Inclusion and supports | Not a separate theme, but individual topics in ungrouped “other” |

| Carers | Carers, families and friends |

| Causes and risk factors | Not a separate theme, but an individual topic in ungrouped “other” |

| Disorder specific | Not a separate theme, but personality disorders in stigma |

| Prevention and early intervention | * Not featured |

| Specific populations | Not a separate theme, but individual topics in ungrouped “other” |

| Lived experience involvement | Consumer and carer involvement |

| Treatments and other interventions | Treatment Medications |

| Peer workforce issues | Peer to peer |

| Stigma, discrimination and associated behaviours | Stigma |

| Recovery | Not a separate theme, but individual topic in ungrouped “other” |

| Not a separate theme, but some aspects in service and system issues | Comorbidity and physical health |

| * Not featured | Experiences of care |

| Not a separate theme, but similar subtheme in service and system issues | Health professionals |

| Not a separate theme, but similar subtheme in service and system issues | Justice |

| * Not featured | Language and communication |

| * Not featured | Legislation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gulliver, A.; Morse, A.R.; Banfield, M. Keeping the Agenda Current: Evolution of Australian Lived Experience Mental Health Research Priorities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138101

Gulliver A, Morse AR, Banfield M. Keeping the Agenda Current: Evolution of Australian Lived Experience Mental Health Research Priorities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138101

Chicago/Turabian StyleGulliver, Amelia, Alyssa R. Morse, and Michelle Banfield. 2022. "Keeping the Agenda Current: Evolution of Australian Lived Experience Mental Health Research Priorities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138101

APA StyleGulliver, A., Morse, A. R., & Banfield, M. (2022). Keeping the Agenda Current: Evolution of Australian Lived Experience Mental Health Research Priorities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138101