Sex Differences in Traditional School Bullying Perpetration and Victimization among Adolescents: A Chain-Mediating Effect

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Chinese Version of Kiddie Machiavellian Scale (KMS)

2.2.2. School Climate Perception Questionnaire

2.2.3. Chinese Version of the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Correlation Results

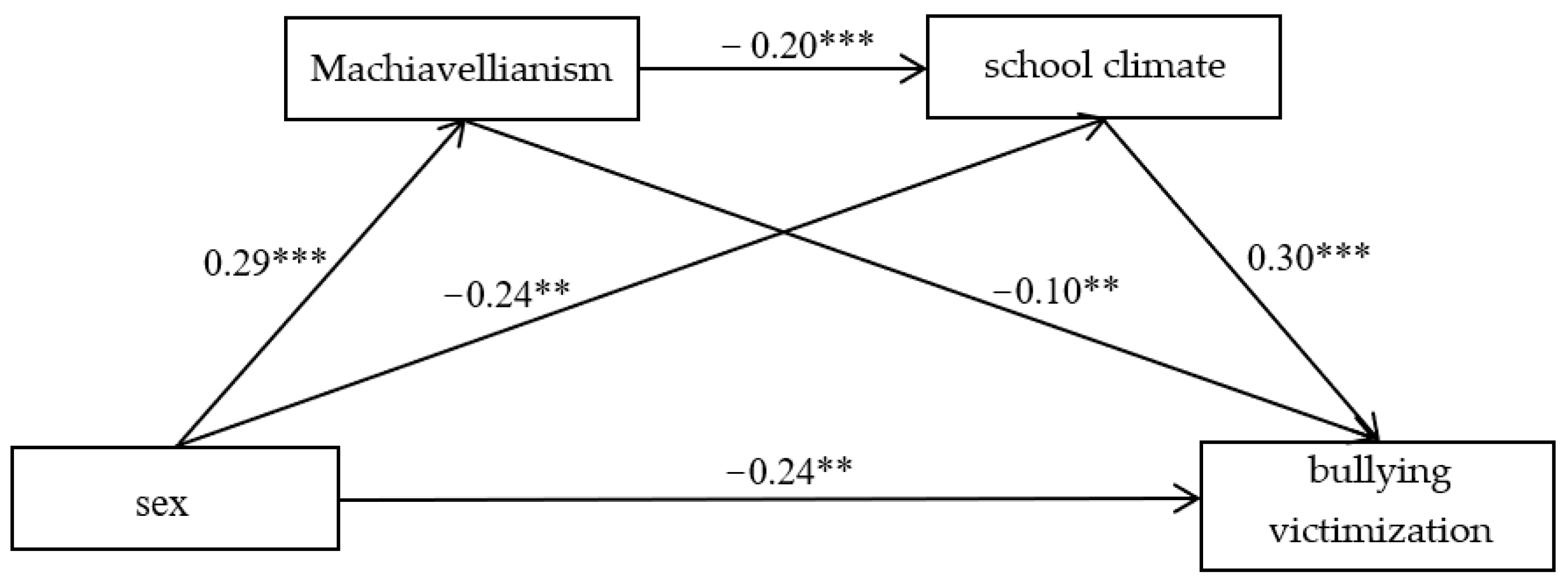

3.3. Chain-Mediating Effect

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, J.; Mccabe, L.; Michelli, N.M.; Pickeral, T. School Climate: Research, Policy, Practice, and Teacher Education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2009, 111, 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.; Harel-Fisch, Y.; Fogel-Grinvald, H.; Dostaler, S.; Hetland, J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Molcho, M.; de Mato, M.G.; Overpeck, M.; Due, P.; et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, C.; Sharkey, J.D.; Reed, L.A.; Chen, C.; Dowdy, E. Bullying victimization and student engagement in elementary, middle, and high schools: Moderating role of school climate. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2018, 33, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2016). Xinhua Commentary: To Curb School Bullying Need Legal Education. Retrieved 10 May 2016. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-05/10/content_5072021.htm (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Strengthening the Construction of Nursery School Safety Risk Prevention and Control System of the Views. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/xw_fbh/moe_2069/xwfbh_2017n/xwfb_17050401/170504_mtbd01/201705/t20170508_303993.html (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Takizawa, R.; Maughan, B.; Arseneault, L. Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2014, 171, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.E.; Wolke, D.; Angold, A.; Costello, E.J. Adult Psychiatric Outcomes of Bullying and Being Bullied by Peers in Childhood and Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatr. 2013, 70, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Sly, P.D.; Whitehouse, A.J.; Zubrick, S.R.; Scott, J. Adolescent peer aggression and its association with mental health and substance use in an Australian cohort. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatr. 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Espelage, D.L. A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkqvist, K.; Lagerspetz, K.M.; Kaukiainen, A. Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggress. Behav. 1992, 18, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, I.; Smith, P.K. Types of bullying behaviour and their correlates. Aggress. Behav. 1994, 20, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wal, M.F.; De Wit, C.A.; Hirasing, R.A. Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iossi Silva, M.A.; Pereira, B.; Mendonça, D.; Nunes, B.; Oliveira, W.A.D. The involvement of girls and boys with bullying: An analysis of sex differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 6820–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furnham, A.; Richards, S.C.; Paulhus, D.L. The dark triad of personality: A 10 year review. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahafar, A.; Randler, C.; Castellana, I.; Kausch, I. How does chronotype mediate gender effect on Dark Triad. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 108, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.; Geis, L.F. Studies in Machiavellianism; Academic Press: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Láng, A.; Lénárd, K. The relation between memories of childhood psychological maltreatment and Machiavellianism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 77, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, J. A review of the research on Machiavellianism. East China Econ. Manag. 2013, 4, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, J.; Keogh, E. Components of machiavellian beliefs in children: Relationships with personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Williams, K.M. The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 2002, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, X.; Sai, X.; Zhao, F.; Wu, H.; Geng, Y. The Dark Triad and sleep quality: Mediating role of anger rumination. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 151, 109484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.; Caravita, S.C. Why do early adolescents bully? Exploring the influence of prestige norms on social and psychological motives to bully. J. Adolesc. 2016, 46, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravita, S.; Cillessen, A.H. Agentic or communal? associations between interpersonal goals, popularity, and bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence. Soc. Dev. 2012, 21, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, C.F.; Cillessen, A.H.N. From indirect aggression to invisible aggression: A conceptual view on bullying and peer group manipulation. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2006, 11, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczkei, T.; Birkas, B.; Kerekes, Z. The Presence of Others, Prosocial Traits, Machiavellianism: A Personality × Situation Approach. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 41, 238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, D.M. Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind, 3rd ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lippa, R.A. Gender differences in personality and interests: When, where, and why? Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 1098–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.M.; Donnellan, M.B.; Navarrete, C.D. A life history approach to understanding the Dark Triad. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Duineveld, J.J.; Middleton, J.P. Pathology, pseudopathology, and the Dark Triad of personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 78, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Koenig, B.L.; Tost, J. Living a fast life. Hum. Nat. 2010, 21, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Rodríguez, J.; Gómez-Jacinto, L.; Hombrados-Mendieta, M.I. Life history theory: Evolutionary mechanisms and gender role on risk-taking behaviors in young adults. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 175, 110752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Fisher, T.D. The power of prestige: Why young men report having more sex partners than young women. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Lavertu, A.N. The reproductive costs and benefits associated with the Dark Triad traits in women. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 110, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.) A future perspective. In The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Swearer, S.M.; Hymel, S. Understanding the Psychology of Bullying Moving Toward a Social-Ecological Diathesis-Stress Model. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Lei, L. Perceived school climate and adolescents’ bullying perpetration: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and peers’ defending. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 109, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, L.M.; Eccles, J.S. Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Espelage, D.L.; Low, S.K.; Jimerson, S.R. Understanding school climate, aggression, peer victimization, and bully perpetration: Contemporary science, practice, and policy. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014, 29, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.C.; Wong, D.S.W. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying in Chinese societies: Prevalence and a review of the whole-school intervention approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The developing ecology of human development: Paradigm lost or paradigm regained. In Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Kansas City, MO, USA, 27–30 April 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.A.; Cauce, A.M.; Gonzales, N.; Hiraga, Y.; Grove, K. An ecological model of externalizing behaviors in African-American adolescents: No family is an island. J. Res. Adolesc. 1994, 4, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, E.R.C. Positionality of African Americans and a Theoretical Accommodation of It: Rethinking Science Education Research. Sci. Educ. 2008, 92, 1127–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Snyder, K.E.; Levinson, H.; Adelson, J.L. Systems View of School Climate: A Theoretical Framework for Research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiani, J.H.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Mendelson, T. Promoting an equitable and supportive school climate in high schools: The role of school organizational health and staff burnout. J. Sch. Psychol. 2014, 52, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.B. Social and cultural influences on school adjustment: The application of an identity-focused cultural ecological perspective. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 34, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A.; Cohen, J.; Guffey, S.; Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. A Review of School Climate Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedewa, A.L.; Ahn, S. The effects of bullying and peer victimization on sexual-minority and heterosexual youths: A quantitative meta-analysis of the literature. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2011, 7, 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.V., Jr. The identification of student personality characteristics related to perceptions of the school environment. Sch. Rev. 1968, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmaini, I.; Mukhtar, M.; Sari, E. The effect of personality, work procedure, and organization climate toward the leader effectiveness of senior high school principals in DKI Jakarta Province. IJER-Indones. J. Educ. Rev. 2017, 4, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Cornell, D.; Konold, T. Internal and external validity of three school climate scales from the School Climate Bullying Survey. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 38, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y.; Ucanok, Z. School Social Climate and Generalized Peer Perception in Traditional and Cyberbullying Status. Kuram Ve Uygul. Egit. Bilimleri. 2012, 12, 2352–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Gini, G. Italian elementary and middle school students’ blaming the victim of bullying and perception of school moral atmosphere. Elem. Sch. J. 2008, 108, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.M.; Charalambous, K.; Davazoglou, A. Primary school teacher interpersonal behavior through the lens of students’ Eysenckian personality traits. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2010, 13, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, K.; Ioannou, M.; Georgiou, S.; Stavrinides, P. Cyberbullying, psychopathic traits, moral disengagement, and school climate: The role of self-reported psychopathic levels and gender. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 41, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Geng, Y.G.; Yan, F.Y.; Zhang, R.X.; Guo, W.W.; Wang, C.D. Mediating and moderating role of resilience between Machiavellianism and problem about depression, anxiety and stress among kiddies. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2017, 25, 879. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Way, N.; Ling, G.; Yoshikawa, H.; Chen, X.; Hughes, D.; Ke, X.; Lu, Z. The influence of student perceptions of school climate on socioemotional and academic adjustment: A comparison of Chinese and American adolescents. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1514–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Zhao, F. Paternal parenting and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A moderated mediation model of deviant peer affiliation and school climate. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.E.N.G.; Liu, X.Q.; Yang, M.S. Reliability and validity of Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire-Chinese version for sibling bullying. China Public Health 2020, 36, 381–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, N.M.; Ayres, C.G.; Lewandowski, C.; Pontes, M.C. Trends in bullying victimization by sex among US high school students. Res. Nurs. Health 2018, 41, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Jones, K. A Study on the Sex Differences in the Bullying Problem of Primary and Middle School Students. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 4, 435–439. [Google Scholar]

- Card, N.A.; Stucky, B.D.; Sawalani, G.M.; Little, T.D. Direct and indin social and psychological motives to bully. J. Adolesc. 2008, 46, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Card, N.A.; Stucky, B.D.; Sawalani, G.M.; Little, T.D. Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1185–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, A.D.; Archer, J. Sex differences in competitive and aggressive behavior: A view from sexual selection theory. Orig. Soc. Mind Evol. Psychol. Child Dev. 2005, 2, 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Enright, R. Belief in altruistic human nature and prosocial behavior: A serial mediation analysis. Ethics Behav. 2020, 30, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Tost, J. I just cannot control myself: The Dark Triad and self-control. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, J.E.; Kavanagh, P.S. Life history strategies and psychopathology: The faster the life strategies, the more symptoms of psychopathology. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2017, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucherah, W.; Finch, H.; White, T.; Thomas, K. The relationship of school climate, teacher defending and friends on students’ perceptions of bullying in high school. J. Adolesc. 2018, 62, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laftman, S.B.; Ostberg, V.; Modin, B. School climate and exposure to bullying: A multilevel study. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2017, 28, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Boyanton, D.; Ross, A.-S.M.; Liu, J.L.; Sullivan, K.; Do, K.A. School climate, victimization, and mental health outcomes among elementary school students in China. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2018, 39, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliot, M.; Cornell, D.; Gregory, A.; Fan, X. Supportive school climate and student willingness to seek help for bullying and threats of violence. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorio, N.B.; Clark, K.N.; Demaray, M.K.; Doll, E.M. School climate counts: A longitudinal analysis of school climate and middle school bullying behaviors. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomes, C.J.; Eduardo, P.C. Personality and aggression: A contribution of the General Aggression Model. Estud. De Psicol. 2016, 33, 443. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Nansel, T.R. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Total | Boys | Girls | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (n = 727) | (n = 356) | (n = 371) | ||

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | |||

| 1. Machiavellianism | 43.03 ± 6.00 | 42.20 ± 6.17 | 43.93 ± 5.73 | −3.92 | <0.001 |

| 2. School climate | 9.01 ± 2.97 | 9.47 ± 3.39 | 8.58 ± 2.49 | 4.03 | <0.001 |

| 3. Bullying perpetration | 6.64 ± 2.26 | 6.88 ± 2.68 | 6.44 ± 1.86 | 2.58 | <0.05 |

| 4. Bullying victimization | 7.37 ± 2.82 | 7.90 ± 3.44 | 6.89 ± 2.05 | 4.78 | <0.001 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Machiavellianism | 1 | |||

| 2. School climate | −0.21 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. Bullying perpetration | −0.21 *** | 0.25 *** | 1 | |

| 4. Bullying victimization | −0.17 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.53 *** | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Guo, H.; Chu, M.; Leng, C.; Qu, C.; Tian, K.; Jing, Y.; Xu, M.; Guo, X.; Yang, L.; et al. Sex Differences in Traditional School Bullying Perpetration and Victimization among Adolescents: A Chain-Mediating Effect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159525

Yang M, Guo H, Chu M, Leng C, Qu C, Tian K, Jing Y, Xu M, Guo X, Yang L, et al. Sex Differences in Traditional School Bullying Perpetration and Victimization among Adolescents: A Chain-Mediating Effect. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159525

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Minqi, Hanxiao Guo, Meimei Chu, Chongle Leng, Chunyu Qu, Kexin Tian, Yuying Jing, Mengge Xu, Xicheng Guo, Liuqi Yang, and et al. 2022. "Sex Differences in Traditional School Bullying Perpetration and Victimization among Adolescents: A Chain-Mediating Effect" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159525

APA StyleYang, M., Guo, H., Chu, M., Leng, C., Qu, C., Tian, K., Jing, Y., Xu, M., Guo, X., Yang, L., & Li, X. (2022). Sex Differences in Traditional School Bullying Perpetration and Victimization among Adolescents: A Chain-Mediating Effect. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159525