Moving from Policy to Practice for Early Childhood Obesity Prevention: A Nationwide Evaluation of State Implementation Strategies in Childcare

Abstract

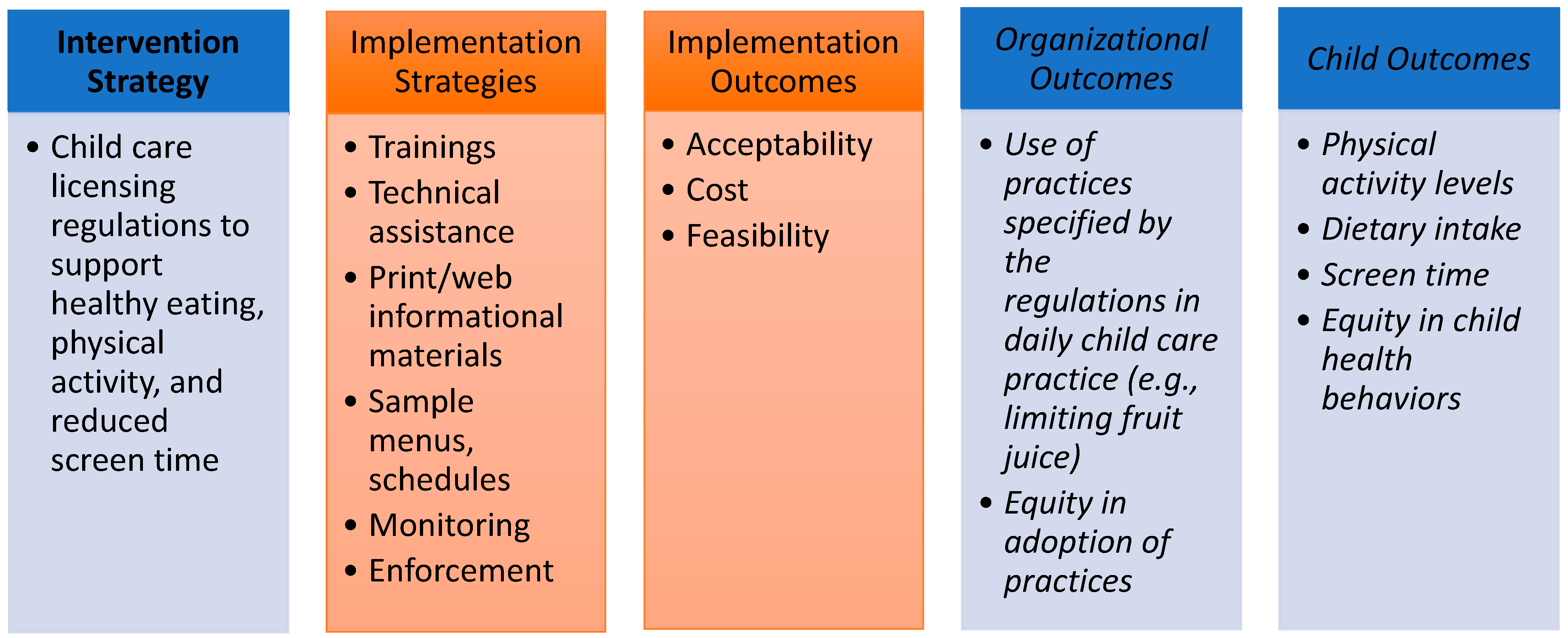

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Identification of the HEPAST Childcare Regulations

2.3. Quantitative Investigation of Implementation Strategies Provided in Each State

2.4. Quantitative Analysis

2.5. Qualitative Investigation of the Perspectives on Policy Implementation

2.6. Integrative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Implementation Strategies Utilized

3.3. Implementation Outcomes (Cost, Feasibility, Fidelity, Acceptability, Equity, Sustainability)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birch, L.; Savage, J.S.; Ventura, A. Influences on the Development of Children’s Eating Behaviours: From Infancy to Adolescence. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2007, 68, s1–s56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Welker, E.B.; Jacquier, E.F.; Catellier, D.J.; Anater, A.S.; Story, M.T. Room for Improvement Remains in Food Consumption Patterns of Young Children Aged 2–4 Years. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1536–1546S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, T.D.; de Brey, C.; Dillow, S.A. Digest of Education Statistics 2016 (NCES 2017-094); National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Alkon, A.; Crowley, A.A.; Neelon, S.E.B.; Hill, S.; Pan, Y.; Viet, N.; Rose, R.; Savage, E.; Forestieri, N.; Shipman, L.; et al. Nutrition and Physical Activity Randomized Control Trial in Child Care Centers Improves Knowledge, Policies, and Children’s Body Mass Index. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stookey, J.D.; Evans, J.; Chan, C.; Tao-Lew, L.; Arana, T.; Arthur, S. Healthy Apple Program to Support Child Care Centers to Alter Nutrition and Physical Activity Practices and Improve Child Weight: A Cluster Randomized Trial. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, K.; Shanafelt, A.; Davey, C.; Anfinson, A.; Zauner, M.; Looby, A.A.; Frost, N.; Nanney, M.S. Provider Adherence to Nutrition and Physical Activity Best Practices Within Early Care and Education Settings in Minnesota, Helping to Reduce Early Childhood Health Disparities. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanney, M.S.; LaRowe, T.L.; Davey, C.; Frost, N.; Arcan, C.; O’Meara, J. Obesity Prevention in Early Child Care Settings: A Bistate (Minnesota and Wisconsin) Assessment of Best Practices, Implementation Difficulty and Barriers. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, A.; Risica, P.; Mena, N.; Lawson, E.; Ankoma, A.; Gans, K.M. An Assessment of Nutrition Practices and Attitudes in Family Child-Care Homes: Implications for Policy Implementation. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercammen, K.A.; Frelier, J.M.; Poole, M.K.; Kenney, E.L. Obesity Prevention in Early Care and Education: A Comparison of Licensing Regulations Across Canadian Provinces and Territories. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.J.; Patterson, E.; Sacks, G.; Billich, N.; Evans, C.E. Preschool and School Meal Policies: An Overview of What We Know about Regulation, Implementation and Impact on Diet in the UK, Sweden, and Australia. Nutrients 2017, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Education, University of Colorado Denver. Achieving a State of Healthy Weight: A National Assessment of Obesity Prevention Terminology in Child. Care Regulations 2010; National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education: Aurora, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaphingst, K.M.; Story, M. Child Care as an Untapped Setting for Obesity Prevention: State Child Care Licensing Regulations Related to Nutrition, Physical Activity and Media Use for Preschool-Aged Children in the United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009, 6, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, M.A.; Cotwright, C.J.; Polhamus, B.; Gertel-Rosenberg, A.; Chang, D. Obesity Prevention in the Early Care and Education Setting: Successful Initiatives across a Spectrum of Opportunities. J. Law. Med. Ethics 2013, 41, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, T.; Corbett, A.; Duffey, K. Early Care and Education Policies and Programs to Support Healthy Eating and Physical Activity: Best Practices and Changes over Time. Research Review: 2010–2016; Healthy Eating Research: Durham, NC, USA, 2017; pp. 2010–2016. Available online: https://healthyeatingresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/her_ece_011718-1.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Ritchie, L.D.; Sharma, S.; Gildengorin, G.; Yoshida, S.; Braff-Guajardo, E.; Crawford, P. Policy Improves what Beverages are Served to Young Children in Child Care. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin Neelon, S.E.; Finkelstein, J.; Neelon, B.; Gillman, M.W. Evaluation of a Physical Activity Regulation for Child Care in Massachusetts. Child. Obes. 2017, 13, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin Neelon, S.E.; Mayhew, M.; O’Neill, J.R.; Neelon, B.; Li, F.; Pate, R.R. Comparative Evaluation of a South Carolina Policy to Improve Nutrition in Child Care. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.K.; Landsverk, J.; Aarons, G.; Chambers, D.; Glisson, C.; Mittman, B. Implementation Research in Mental Health Services: An Emerging Science with Conceptual, Methodological and Training Challenges. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2009, 36, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.S.; Benjamin, S.E.; Ammerman, A.S.; Ball, S.C.; Neelon, B.H.; Bangdiwala, S.I. Nutrition and Physical Activity in Child Care: Results from an Environmental Intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRowe, T.L.; Tomayko, E.J.; Meinen, A.M.; Hoiting, J.; Saxler, C.; Cullen, B. Active Early: One-Year Policy Intervention to Increase Physical Activity among Early Care and Education Programs in Wisconsin. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Jones, J.; Williams, C.M.; Finch, M.; Wyse, R.J.; Kingsland, M.; Tzelepis, F.; Wiggers, J.; Williams, A.J.; Seward, K.; et al. Strategies to Improve the Implementation of Healthy Eating, Physical Activity and Obesity Prevention Policies, Practices or Programmes within Childcare Services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD011779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, L.; Speirs, K.E.; Slesinger, N. Implementation Strategies Used by States to Support Physical Activity Licensing Standards for Toddlers in Early Care and Education Settings: An Exploratory Qualitative Study. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.S.; Contreras, D.; Gold, A.; Keim, A.; Oscarson, R.; Peters, P.; Procter, S.; Remig, V.; Smathers, C.; Mobley, A.R. Evaluation of Nutrition and Physical Activity Policies and Practices in Child Care Centers within Rural Communities. Child. Obes. 2015, 11, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigman-Grant, M.; Christiansen, E.; Fernandez, G.; Fletcher, J.; Johnson, S.L.; Branen, L.; Price, B.A. Child Care Provider Training and a Supportive Feeding Environment in Child Care Settings in 4 States, 2003. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8, A113. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, E.L.; Mozaffarian, R.S.; Frost, N.; Ayers Looby, A.; Cradock, A.L. Opportunities to Promote Healthy Weight Through Child Care Licensing Regulations: Trends in the United States, 2016–2020. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.K.; Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C. Implementation Strategies: Recommendations for Specifying and Reporting. Implement Sci. 2013, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, F.G.; Kellison, J.G.; Boyd, S.J.; Kopak, A. A Methodology for Conducting Integrative Mixed Methods Research and Data Analyses. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2010, 4, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seward, K.; Finch, M.; Yoong, S.L.; Wyse, R.; Jones, J.; Grady, A.; Wiggers, J.; Nathan, N.; Conte, K.; Wolfenden, L. Factors that Influence the Implementation of Dietary Guidelines Regarding Food Provision in Centre Based Childcare Services: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. 2017, 105, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Blaser, C.; Geno-Rasmussen, C.; Shuell, J.; Plumlee, C.; Gargano, T.; Yaroch, A.L. Improving Nutrition and Physical Activity Policies and Practices in Early Care and Education in Three States, 2014–2016. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, E73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, J.B.; Lou, C.; Hahn, H.; Lauderback, E.; Quakenbush, C. Public Spending on Infants and Toddlers in Six Charts: A Kids’ Share Brief; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100198/public_spending_on_infants_and_toddlers.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Otten, J.J.; Bradford, V.A.; Stover, B.; Hill, H.D.; Osborne, C.; Getts, K.; Seixas, N. The Culture of Health in Early Care and Education: Workers’ Wages, Health and Job Characteristics. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N Policy Regulations | |

|---|---|

| Nutrition regulations, N (%) | 98 (50.0) |

| Regulatory language is such that an update to the Child and Adult Care Food Program standards would result in an automatic update to nutrition standards required by all licensed programs | 24 (12.2) |

| Drinking water is made available to children throughout the day or in frequent intervals | 35 (17.9) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages are not served | 13 (6.6) |

| No more than 4-6oz of 100% juice is served per day for children aged 1 to 6 years | 11 (5.6) |

| Grain-based desserts or sugary/sweet foods are served once per week | 4 (2.0) |

| At least half of the grains/breads served in meals and snacks must be whole grain-rich | 1 (0.5) |

| Fruits and/or vegetables are served at each eating occasions | 6 (3.1) |

| Nutrition standards apply to food brought from home | 4 (2.0) |

| Physical activity regulations, N (%) | 56 (28.6) |

| Toddlers are provided 60–90 min of moderate/vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily | 5 (2.6) |

| Preschoolers are provided 90–120 min of moderate/vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily | 19 (9.7) |

| Outdoor play required for at least 60 min per day | 28 (14.3) |

| Indoor time in place of outdoor time if weather does not permit | 3 (1.5) |

| Staff are trained in promoting moderate/vigorous physical activity (MVPA) | 1 (0.5) |

| Screentime regulations, N (%) | 38 (19.4) |

| No screentime for children <2 years old | 14 (7.1) |

| Screentime limited for children ages 2–5 years old to less than 30 min per week | 16 (8.2) |

| Any screentime provided must be educational (includes physical education) or children are specifically not allowed to watch marketing of unhealthy foods/beverages | 8 (4.1) |

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Unique states completing surveys, N | 39 (100) |

| Mean number of childcare centers overseen by state, mean (SD) | 2496 (2843) |

| Number of state licensing staff, mean (SD) | 71.5 (12.5) |

| Ratio of childcare centers to licensing staff, mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.02) |

| Non-Hispanic white residents, N (%) | 67.1 (16.8) |

| Residents living in poverty, N (%) | 12.2 (2.5) |

| Census region, N (%) | |

| Northeast | 7 (18.0) |

| South | 15 (38.5) |

| Midwest | 9 (23.1) |

| West | 8 (20.5) |

| Total survey participants, N 1 | 89 (100) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.3 (10.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |

| White | 68 (82.9) |

| Black | 7 (8.5) |

| Hispanic | 4 (4.9) |

| Asian | 2 (2.4) |

| Mixed race | 1 (1.2) |

| Years working in licensing or at organization, mean (SD) | 13.1 (8.8) |

| Highest educational degree, N (%) | |

| Associate/Some College | 5 (5.8) |

| College | 38 (43.7) |

| Masters | 41 (47.1) |

| Doctorate | 3 (3.5) |

| Licensing Staff | Non-Profit Partners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) | N | N (%) | |

| Total regulations | 150 (100) | 114 (100) | ||

| Mean regulations by state (SD) | 32 | 4.7 (2.0) | 22 | 5.2 (2.1) |

| Mean implementation supports provided per regulation (SD) | 143 | 3.3 (1.9) | 114 | 4.4 (2.1) |

| Activities office promotes to help implement policy | ||||

| Training | 141 | 81 (57.5) | 114 | 102 (89.5) |

| Consultation/technical assistance | 142 | 138 (97.2) | 114 | 99 (86.8) |

| Print materials, mail | 141 | 47 (33.3) | 114 | 48 (42.1) |

| Print materials, web | 139 | 74 (53.2) | 114 | 65 (57.0) |

| Training guides, implementation guidelines, or other documents | 139 | 70 (50.4) | 114 | 76 (66.7) |

| Suggested curricula or lesson plans | 136 | 16 (11.8) | 114 | 52 (45.6) |

| Suggested menus or schedules | 136 | 41 (30.2) | 114 | 58 (50.9) |

| Training types offered | ||||

| Web-based | 77 | 53 (68.8) | 101 | 99 (98.0) |

| In-person | 77 | 67 (87.0) | 101 | 81 (80.2) |

| Offered in multiple locations | 76 | 61 (80.3) | 101 | 98 (97.0) |

| Technical assistance offered | ||||

| Web-based | 134 | 53 (39.6) | 97 | 88 (90.7) |

| In-person | 137 | 135 (98.5) | 97 | 89 (91.8) |

| Phone | 133 | 115 (86.5) | 97 | 90 (92.8) |

| Strategies for monitoring regulations | ||||

| Annual paperwork | 139 | 50 (36.0) | Not applicable | |

| Licensing visits | 145 | 141 (97.2) | ||

| CACFP monitors (CACFP regs only) | 76 | 53 (69.7) | ||

| How licensing assesses compliance | ||||

| Review menus or schedules | 140 | 118 (84.3) | ||

| Observe meal or physical activity | 139 | 126 (90.7) | ||

| Review contents pantry/fridge (nutrition regs only) | 69 | 34 (49.3) | ||

| Other | 131 | 35 (26.7) | ||

| Action for non-compliance | ||||

| Verbally discussed with provider | 143 | 137 (95.8) | ||

| Written warning | 144 | 73 (50.7) | ||

| Provided training materials | 141 | 52 (36.9) | ||

| Offered technical assistance | 139 | 96 (69.1) | ||

| Monetary fine | 138 | 1 (0.72) | ||

| Complaint is filed | 139 | 11 (7.9) | ||

| Citation of violation | 138 | 43 (31.2) | ||

| Other | 138 | 41 (29.7) | ||

| Theme | Descriptive Quantitative Data | Exemplar Interview Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation Strategies | ||

| Monitoring is the primary strategy for licensing staff | Survey: 97% of survey participants reported checking for childcare program adherence to healthy eating, physical activity, or screentime regulations during monitoring visits. | “So our primary role is monitoring, but we are mandated to also provide some technical assistance and consultation to programs.”[Licensing staff] “Kind of like I mentioned, a lot of the rules around eating and physical activity and screentime, we really don’t have a lot of rule violations for those because they’re kind of hard to regulate. Because when the license is there, it’s just a quick snapshot of what’s happening. And so it’s kind of hard to know if they’re really following those rules.”[Licensing staff] |

| Training is a strategy used by some licensing agencies, but primarily by non-profit partners | Website: 2% of available healthy eating, physical activity, or screentime-related training appeared to be led by the licensing agency; the remainder were led by non-profit partners. Survey: 57.5% of state licensing agencies report providing training while 90% of non-profit partners provide training. | “We’re contracted through the state to provide a variety of training, not just on those topics you mentioned, but we offer options. And these options are to meet the state minimum standards for licensing that would be face to face, online, home study kits, onsite classes, phone and in-person support.” [Non-profit partner] |

| Technical assistance is provided, but the dose and meaning of this vary substantially | “Technical assistance can be simply the licensing specialist is there for a visit they see a noncompliance and then they talk with the provider and provide suggestions on how compliance could be maintained or attained, and also when the provider asks the question and says, hey, I’m struggling with X, we can provide information on how they might be successful in solving their problem.” [Licensing staff] | |

| Implementation Outcomes | ||

| Feasibility issues related to staff turnover, lack of resources, weather | “I think they’re overwhelmed with how many guidelines there are to be quality… And I think it goes back to what [name] said earlier with the funding-- being able to pay their staff and keep staff in there, that, not that revolving door of having to hire new staff. I think that kind of pulls it down. And I think that’s the struggle there.” [Non-profit partner] “I would like to see more outdoor activities, I would like to see more outdoor trainings, that outdoor classroom, and because of our weather here, it’s, you know, in the summer, it’s hot and humid… I think they all really do try to follow good physical fitness and outdoor, it’s a requirement, and they’re pretty good about following it, I think. But they do struggle with that outdoor play. So here it’s just the humidity here can be so stifling and they need to be outside.” [Non-profit partner] | |

| Fidelity to HEPAST regulations is stronger for nutrition, especially if providers participate in and have support from CACFP | “Healthy eating, I feel like is definitely the easiest to regulate… if they’re on the food program, if they want the reimbursement, they have to do it…If they’re not on a food program, I would say, not followed as closely. But physical activity and screentime are just really hard to regulate, and I think there’s just a lot of providers who just feel like that’s a lot of work.” [Licensing staff] “I think for healthy eating regulations are followed more closely than for physical activity and screentime. Because nutrition is monitored, if they want to participate in the food program.” [Non-profit partner] “…One of their licensing monitors come in and really because they’re charged with health and safety stuff, their priority is: ‘is a child going to choke, is our electrical outlet that’s covered? Are there things protruding from the fence that’s going to harm a child?’ And so with that being their high priority, when they’re looking at the meals, you know, they’re looking, you know, OK, veggie, fruit, a bread of some sort or grain, a meat and milk. They’re fine. They’re keep me going, but I don’t think they go to the extent of verifying ‘is that milk 1% or is it or is it whole milk? Is that a whole grain? Have they had a whole grain at some other time during the day? Is the cinnamon roll, breakfast bar or cinnamon roll or something, is that is that allowed?’ Like they are just, so it’s like ‘oh it’s of minimal consequence from health -- from a safety standpoint’. So they just kind of move on.” [Non-profit partner] | |

| Appropriateness—varying perceptions of whether or not the HEPAST regulations are appropriate to require for childcare providers | Survey: 13% of licensing staff ranked healthy eating, physical activity, and screentime rules as less of a priority compared to other regulations, but most rated them as similarly important. Meanwhile, among non-profit partners, 26% ranked HEPAST rules as less important than other regulations. | “Okay, [our state] has strong childcare regulations. Could they be stronger? Sure. But I think that what we tried to do was to balance, to have an effective balance between the needs of providers and the needs of children. So I think they’re just right. Goldilocks.” [Licensing staff] “Yeah, we get a lot of pushback from home providers any time there are new rules. And we’ve got a lot of pushback on the screentime rule because home providers often make the argument that parents choose home providers because they want them to feel like they’re at home and they don’t want it to feel like a childcare center.” [Non-profit partner] “But I think, unfortunately, they are tired and not have not always received the education or knowledge that they need to understand why it’s important. And we know if they don’t know the why, they’re definitely not going to do it. So I think right now, unfortunately, they would say, oh, it’s enough or maybe even too much. But I don’t think it’s because there’s a lack of passion for children in the state. I think it’s just a lack of knowing.” [Non-profit partner] “I think they agree with them in principle, but.. there’s so much paperwork that are just stretched so thin to be able to implement these regulations.” [Non-profit partner] |

| Equity a. Language b. Income c. Race/ethnicity d. Technology | Survey findings:

| “Now, providing training in any other languages, I don’t know. I know research and referral does tend to have a Spanish speaking person on staff. But, yeah, there’s not as much of that. I mean, there’s also but there are people who English is not their first language and we’re definitely not necessarily always meeting their needs, I am sure.” [Licensing staff] “And so I think access is different, people are way more spread out. So there’s this rural component as far as, like, getting to trainings that can be more done in the southern part of the state. And also Internet access is more difficult in the southern half [rural part] of the state.” [Non-profit partner] “But I do think there are some inherent challenges. It may be, it might not be the home/center type thing, it might be more community, you know, geographic location. For example, when I talk about the food deserts and things, it could be related to that, some culture, when you get into some parts of the delta in our state, and just the intergenerational poverty that’s existed for long periods of time. To not acknowledge that is you’re not going to make any progress. You aren’t aware of some of that history and culture.” [Non-profit partner] “With family childcare we just have to do something separate to get them more involved because they’re just a unique group. And finding the time…We offer Saturday trainings sometimes just geared to family childcare just to get them out and to get them the training that they need and talk about the topics that we need to talk about.” [Non-profit partner] “But whenever we talk about cultural diversity and just talking about food, for example, it always comes down to like the taco, you know -- and that kind of reeks of tokenism in a sense, you know, and being able to say, ‘hey, we checked off, you know, something that’s Hispanic Latino, excuse me, a Latin American type of food staple’. But I don’t really think it goes in the depth of like what can providers in their respective communities do to make their foods acceptable under these standards.” [Non-profit partner] |

| Sustainability | “I do not think a one and done training gives them what they need. I think if you want anything to be meaningful and impactful, you have to attach some kind of coaching with it.” [Non-profit partner] | |

| Cost | “[Smaller providers’] monthly bills take most of the income that the center is earning. They have a harder time…just because maybe their finances are more limited than a larger [program]-- you know one that’s a corporation type facility where it’s maybe a bigger organization, where they have a little more free money.” “[There is] so much turnover among our teachers, because when we hired them at minimum wage or a few cents over that with very few benefits, and I’m talking about all the childcare centers in the area, not just the four that we oversee. But, that teacher might decide, well, I can make more money at the hamburger place down the street and they’re gone. So we have to do all of our training all over again with the new teachers that come in there and there. Again, it’s just a cycle. And as soon as they find something better, they’re gone. If we had the funding to give them some sort of monetary incentive to stay with us or give them the benefits that they need to stay with us, that would just really help us to improve the quality of childcare across the board, not just for us, but in all the centers. If the money were available. And I don’t know the answer to that as to how to get more money for these teachers.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenney, E.L.; Mozaffarian, R.S.; Ji, W.; Tucker, K.; Poole, M.K.; DeAngelo, J.; Bailey, Z.D.; Cradock, A.L.; Lee, R.M.; Frost, N. Moving from Policy to Practice for Early Childhood Obesity Prevention: A Nationwide Evaluation of State Implementation Strategies in Childcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610304

Kenney EL, Mozaffarian RS, Ji W, Tucker K, Poole MK, DeAngelo J, Bailey ZD, Cradock AL, Lee RM, Frost N. Moving from Policy to Practice for Early Childhood Obesity Prevention: A Nationwide Evaluation of State Implementation Strategies in Childcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610304

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenney, Erica L., Rebecca S. Mozaffarian, Wendy Ji, Kyla Tucker, Mary Kathryn Poole, Julia DeAngelo, Zinzi D. Bailey, Angie L. Cradock, Rebekka M. Lee, and Natasha Frost. 2022. "Moving from Policy to Practice for Early Childhood Obesity Prevention: A Nationwide Evaluation of State Implementation Strategies in Childcare" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610304

APA StyleKenney, E. L., Mozaffarian, R. S., Ji, W., Tucker, K., Poole, M. K., DeAngelo, J., Bailey, Z. D., Cradock, A. L., Lee, R. M., & Frost, N. (2022). Moving from Policy to Practice for Early Childhood Obesity Prevention: A Nationwide Evaluation of State Implementation Strategies in Childcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610304