How Does a Healthy Interactive Environment Sustain Foreign Language Development? An Ecocontextualized Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. Different Context Schools and Views

2.2. Application Studies of Context Views in L2 or FL Development

3. Towards an Ecocontextualized Approach

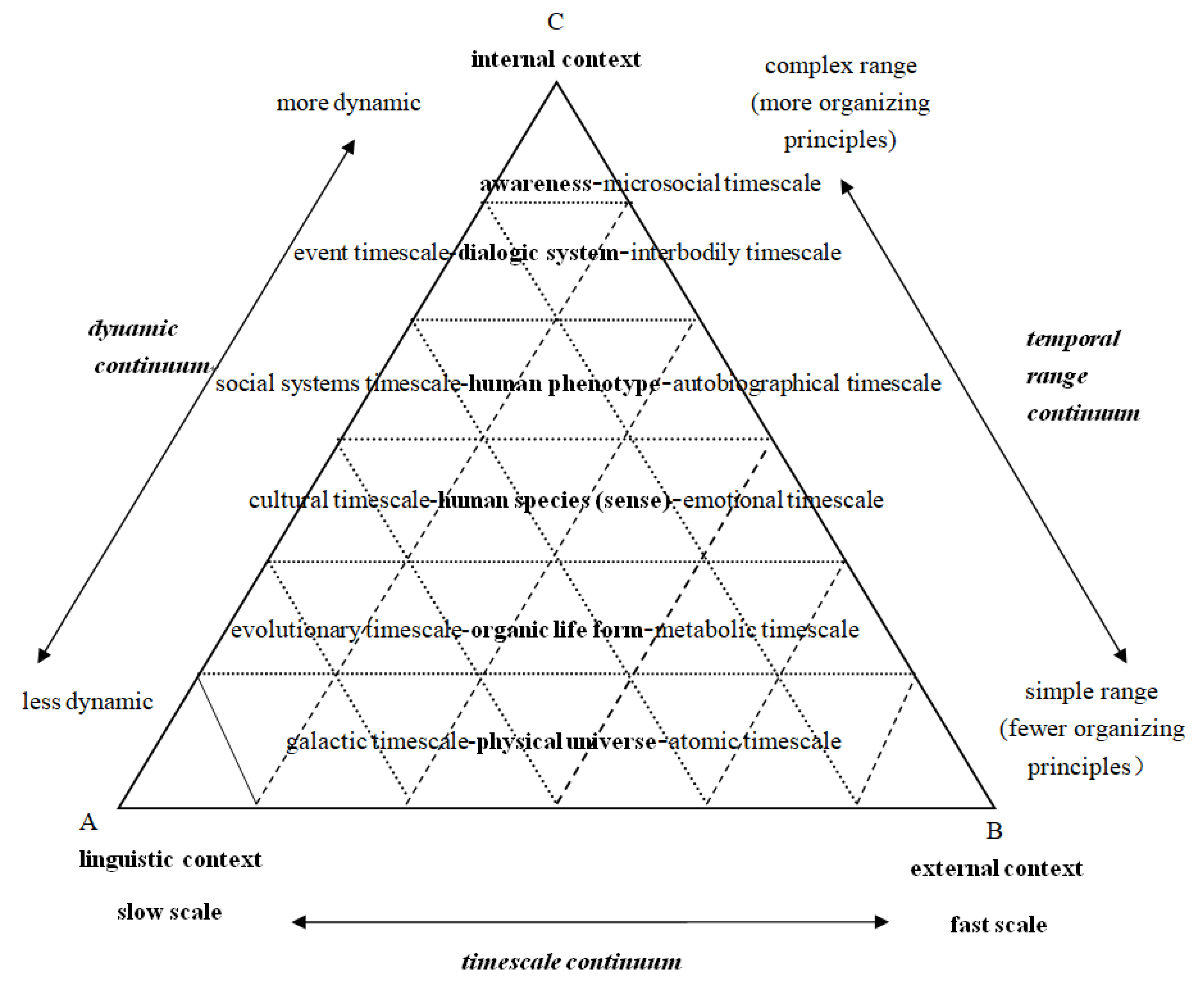

3.1. A Tiered Ecointeractive Context-Oriented Perspective to FLD

3.2. The Interactive Strata and Relationships

3.2.1. Stratification of External Context in ECM

3.2.2. Stratification of Linguistic Context in ECM

3.2.3. Stratification of Internal Context in ECM

3.2.4. The Intrastratal and Interstratal Relationships

3.2.5. The Main Interactional Process(ing)

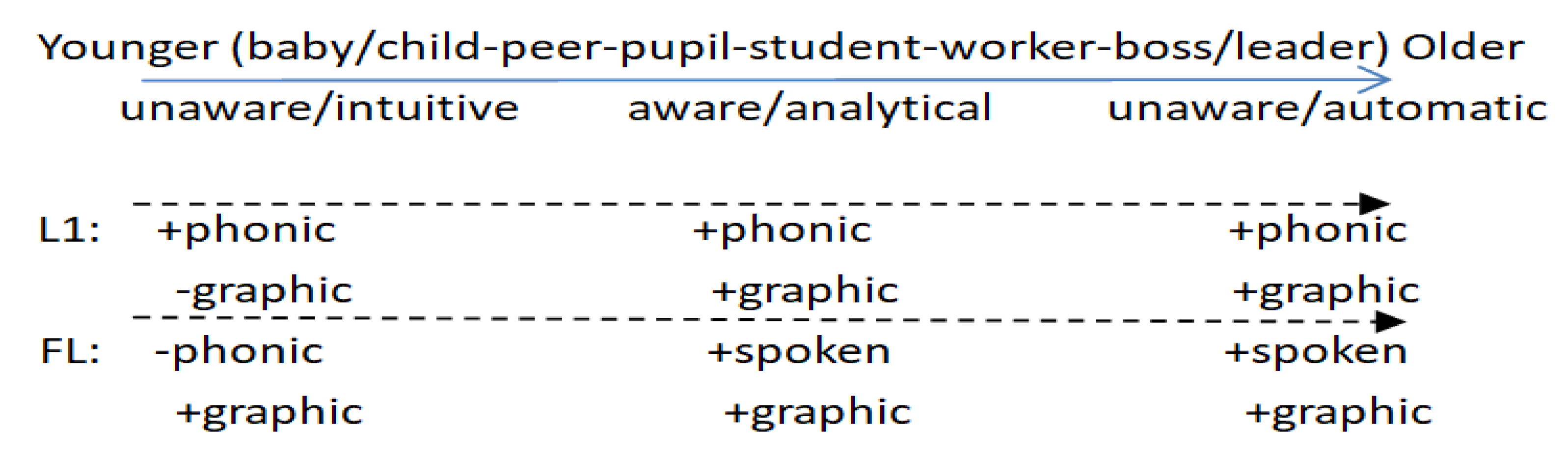

3.3. A Route to Sustainable FLD: Sequenced Implicit/Phonic-Explicit/Graphic Processing

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Recruitments

4.2. Questionnaire and Interview/Oral Test

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Early Stage Survey Results

5.2. Late Stage Survey Results

5.3. Interview/Oral Test Results, Elicited Language Abilities, and Examination Scores

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gass, S.; Mackey, A.; Ross-Feldman, L. Task-Based Interactions in Classroom and Laboratory Settings. Lang. Learn. 2005, 55, 575–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacane, A.; Howard, M. The role of learner status in the acquisition of pragmatic markers during study abroad: The use of ‘like’ in L2 English. J. Pragmat. 2019, 146, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lier, L. The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning: A Sociocultural Perspective; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Firth, J.R. Personality and Language in Society. Sociol. Rev. 1950, a42, 37–52, reprinted in Papers in Linguistics; Oxford University Press, London, UK, 1959; pp. 1934–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Hasan, R. Language, Context and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schieffelin, B.; Ochs, E. Language socialization. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1986, 15, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S.D. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. The role of awareness in second language learning. Appl. Linguist. 1990, 11, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantolf, J. Sociocultural and second language learning research: An exegesis. In The Ninth Annual Sociocultural Theory Workshop; Routledge: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, T. Discourse and Context: A Sociocognitive Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. The genesis of higher mental functionas. In The Concept of Activity in Social Psychology; Wertsch, J., Ed.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 144–188. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Thought and Language; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, I.J. Semantics; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Collentine, J. The effects of learning contexts on morphosyntactic and lexical development. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2004, 26, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, B.F. (Ed.) What makes us think that students who study abroad become fluent? In Second Language Acquisition in a Study Abroad Context; Johne Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lafford, B.A. The effect of the context of learning on the use of communication strategies by learners of Spanish as a second language. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2004, 26, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T.; Zenuk-Nishiide, L. The impact of learning contexts on proficiency, attitudes, and L2 communication: Creating an imaged international community. System 2008, 36, 566–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, P. A classroom perspective on the negotiation of meaning. Appl. Linguist. 1998, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, D. Methods in second language classroom research: A critical review. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 1991, 13, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J.; Fleckenstein, J.; Leucht, M.; Köller, O.; Möller, J. The Long-Term Proficiency of Early, Middle, and Late Starters Learning English as a Foreign Language at School: A Narrative Review and Empirical Study. Lang. Learn. 2020, 70, 1091–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaekel, N.; Schurig, M.; van Ackern, I.; Ritter, M. The impact of early foreign language learning on language proficiency development from middle to high school. System 2022, 106, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, E. Linguistic resources for socializing humanity. In Rethinking Linguistic Relativity; Gumperz, J.J., Levinson, S.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 407–437. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, D. Studying speaking to inform second language learning: A conceptual overview. In Studying Speaking to Inform Second Language Learning; Boxer, D., Cohen, A.D., Eds.; World Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, G. Four perspectives on L2 pragmatic development. Appl. Linguist. 2001, 22, 502–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufon, M.A. The Acquisition of Linguistic Politeness in Indonesian as a Second Language by Sojourners in Naturalistic Interactions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Manoa, HI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, A.S. Second Language Aacquistion Process in the Classroom: Learning Japanese; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, D. On communicative competence. In Sociolinguistics; Pride, J.B., Holmes, J., Eds.; Penguin: Harmordsworth, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgil, P. Sociolinguistics: An introduction to Language and Society; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. Towards a language-based theory of learning. Linguist. Educ. 1993, 5, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K. Language and Education; Jonathan, J., Ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rampton, B.; Roberts, C.; Leung, C.; Harris, R. Methodology in the Analysis of Classroom Discourse. Appl. Linguist. 2002, 23, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, D. The Social Turn in Second Language Acquisition; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.A. Qualitative Theory and Methods in Applied Linguistics Research. TESOL Q. 1995, 29, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, D.; Wilson, D. Relevance: Communication and Cognition, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- John-Steiner, V.; Panofsky, C.P.; Smith, L.W. Sociocultural Approaches to Language and Literacy: An Interactionist Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.D. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching; Prentice Hall Regents: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. The Study of Second Language Acquisition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbown, P.M.; Spada, N. How Languages are Learned; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, D. Extended, Embodied Cognition and Second Language Acquisition. Appl. Linguist. 2010, 31, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collentine, J.; Freed, B.F. Learning Context and Its Effects on Second Language Acquisition: Introduction. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2004, 26, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, G. Semantics; Penguin: Harmordsworth, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzanella, C. Discourse Markers in Italian: Towards a ‘Compositional’ Meaning. In Approaches to Discourse Particles; Fisher, K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 449–464. [Google Scholar]

- Zwaan, R.A.; Radvansky, G.A. Situation models in language comprehension and memory. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 123, 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-K.; Hwang, G.-J.; Chang, Y.-T.; Chang, C.-K. Effects of caption modes on English listening comprehension and vocabulary acquisition using handheld devices. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2013, 16, 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, R. What’s going on: A dynamic view of context in language. In The Seventh LACUS Forum; Copeland, J.E., Davis, P.W., Eds.; Hornbeam Press: Columbia, SC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cloran, C. Context, material situation, and text. In Text and Context in Functional Linguistics; Ghadessey, M., Ed.; Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 177–217. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning; Arnold: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J. Semantics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.-Z. The Role of sequenced interactional strata and frequencies in constructing L2 discourse domain: Sound-meaning mapping prioritizing hypothesis. Foreign Lang. China 2022, 9, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmslev, L. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R. Analyzing Genre: Functional Parameters. In Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School; Christie, F., Martin, J.R., Eds.; Continuum: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. Construing Experience Through Meaning: A Language-Based Approach to Cognition; Cassell: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Siakaluk, P.D.; Pexman, P.M.; Aguilera, L.; Owen, W.J.; Sears, C.R. Evidence for the activation of sensorimotor information during visual word recognition: The body object interaction effect. Cognition 2008, 106, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrell, P.L.; Eisterhold, J.C. Schema Theory and ESL Reading Pedagogy. TESOL Q. 1983, 17, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, R. Literacy and Language Teaching; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, D. Discourse domains: The cognitive context of speaking. In Studying Speaking to Inform Second Language Learning; Boxer, D., Cohen, A.D., Eds.; World Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. (Ed.) The Sociology of Language: An interdisciplinary social science approach to language in society. In Advances in the Sociology of Language; Mouton: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1972; Volume 1, pp. 217–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zuengler, J. Performance variation in NS-NNS interactions: Ethnolinguistic difference, or discourse domain? In Variation in Second Language Acquisition (Discourse and Pragmatics); Gass, S., Madden, C., Preston, D., Selinker, L., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 228–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, M. Effect of Alignment on L2 Written Production. Appl. Linguist. 2014, 36, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uryu, M.; Steffenson, S.V.; Kramsch, C. The ecology of intercultural interaction: Timescales, temporal ranges and identity dynamics. Lang. Sci. 2014, 41, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Chalmers, D. The extended mind. Analysis 1998, 58, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barselou, L. Grounded cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, P. Attention, memory, and the noticing hypothesis. Lang. Learn. 1995, 45, 283–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Language Sense and Language Abilities; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2005; pp. 172–173. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.Y.; Li, D.C. Form-focused remedial instruction:an empirical study. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2002, 12, 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Integrated Abilities of English Translation; Level 2; Foreign Languages Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. Teaching Spoken Stance Markers: A Comparison of Receptive and Productive Practice. Eur. J. Appl. Linguist. TEFL 2016, 5, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C.S.L.; Fisher, S.E.; Hurst, J.A.; Vargha-Khadem, F.; Monaco, A.P. A forkhead-domain gene is mutated in a severe speech and language disorder. Nature 2001, 413, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.C.; Wu, B.H.; Wang, L.D. Neurolinguistics; Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press: Shanghai, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, A. Predictive power of the sources of primary school students’ self-efficacy beliefs on their self-efficacy beliefs for learning and performance. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. Modern Sociopsychlogy; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, M. Principles and evaluations of role-playing-based teaching. Educ. Sci. 2004, 20, 28–31, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.-Z.; Dai, C.Y.; Dong, L.Z. The development of interlanguage pragmatic markers in alignment with role relationships. Pragmatics 2021, 31, 617–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andringa, S.; De Glopper, K.; Hacquebord, H. Effect of Explicit and Implicit Instruction on Free Written Response Task Performance. Lang. Learn. 2011, 61, 868–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.-Z. Role-based Interaction Analysis for FLL: A Sociocognitive UBL Perspective. Lang. Teach. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Learners | Listening & Speaking | Reading & Writing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | t | p | m | t | p | |

| senior NSMMP-SMMP | 3.08/2.60 | −1.06 | 0.34 | 3.76/3.54 | −0.77 | 0.48 |

| tertiary NSMMP-SMMP | 2.68/2.78 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 3.82/3.81 | −0.33 | 0.77 |

| Types of Learners | Listening & Speaking | Reading & Writing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | t | p | m | t | p | |

| Senior NSMMP-SMMP | 11.91/9.28 | −5.11 | 0.00 | 13.39/10.42 | −5.77 | 0.00 |

| Tertiary NSMMP-SMMP | 11.93/9.61 | −5.49 | 0.00 | 12.85/10.59 | −4.69 | 0.00 |

| Types of Learners | Fluency | Accuracy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | sd | t | p | m | sd | t | p | |

| junior NSMMP-SMMP | 80.43/86.06 | 4.60/6.21 | −2.22 | 0.009 | 79.33/81.16 | 6.52/5.65 | −0.82 | 0.418 |

| (translation multiple choices) | (grammar multiple choices) | |||||||

| tertiary NSMMP-SMMP | 2.17/1.70 | 1.11/1.14 | 1.89 | 0.063 | 4.41/3.90 | 1.44/1.37 | 1.68 | 0.097 |

| 95% Confidence Interval for Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | p | MD | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| SHSEE | −2.167 | 67.165 | 0.034 | −2.992 | 1.381 | −5.749 | −0.236 |

| UEWE | −0.561 | 63.196 | 0.577 | −0.820 | 1.462 | −3.742 | 2.103 |

| UEOE | −2.187 | 85.258 | 0.032 | −3.888 | 1.778 | −7.423 | −0.353 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, H.-Z. How Does a Healthy Interactive Environment Sustain Foreign Language Development? An Ecocontextualized Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610342

Xiao H-Z. How Does a Healthy Interactive Environment Sustain Foreign Language Development? An Ecocontextualized Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610342

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Hao-Zhang. 2022. "How Does a Healthy Interactive Environment Sustain Foreign Language Development? An Ecocontextualized Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610342

APA StyleXiao, H.-Z. (2022). How Does a Healthy Interactive Environment Sustain Foreign Language Development? An Ecocontextualized Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610342