The Experience of Patients in Chronic Care Management: Applications in Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Value for Public Health

Abstract

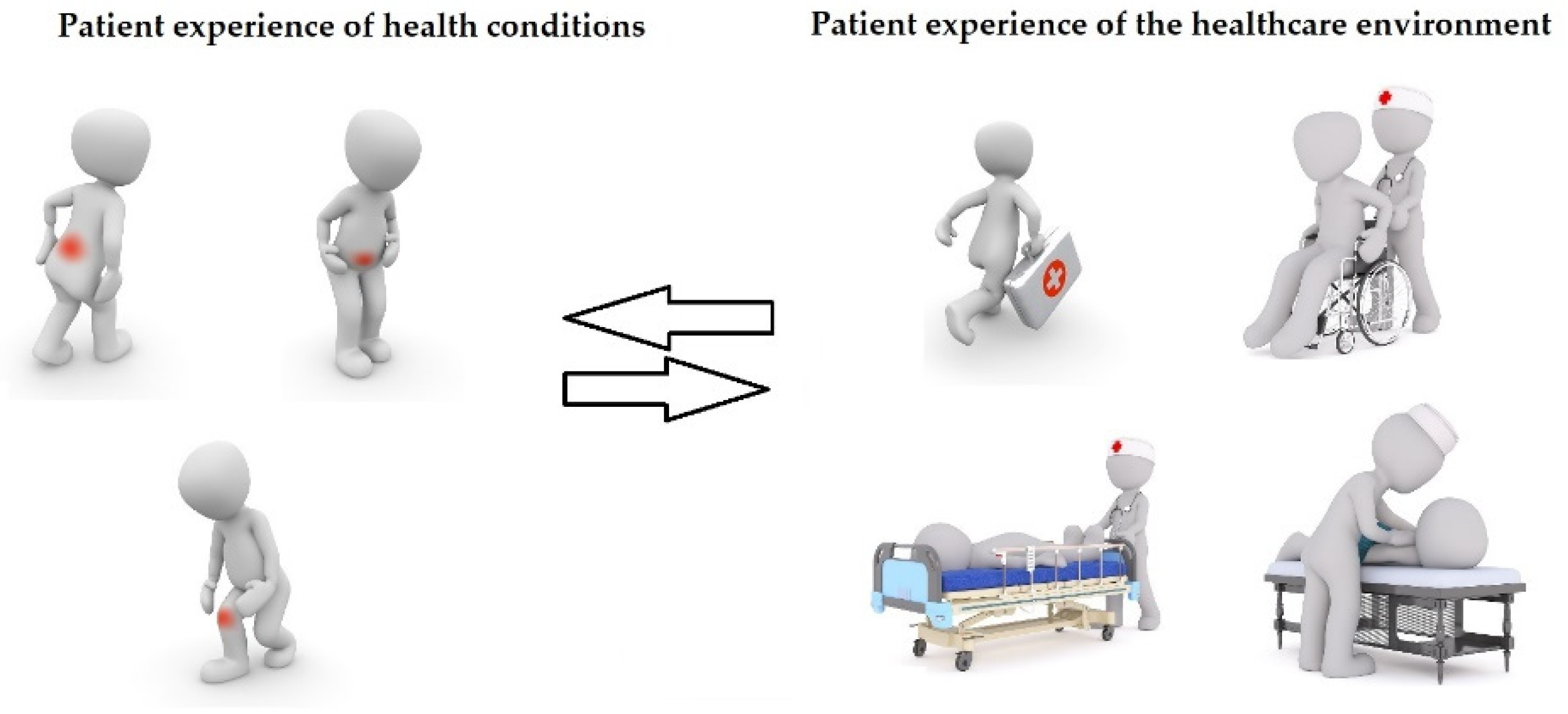

:1. Introduction

- Patient adherence (ability to understand medical advice, actively participate to decisions, comply with prescriptions);

- Caregiver burden (ability to support the patient and maintain one’s own job, societal role, responsibilities and wellbeing);

- Quality, safety, and cost-effectiveness of care (avoiding complications, duplicative visits, pharmacological overtreatment, inappropriate care, waiting lists extension, emergency care abuse).

- Supporting the ordinary work of chronic care managers, case managers and clinical managers;

- Focusing on the connections between units (i.e., single professionals, wards and facilities) in addition to their single performances;

- Enhancing the benefits of clinical care with organizational and educational interventions;

- Providing specific outcomes for such interventions;

- Identifying the need for complementary interventions (i.e., social prescribing);

- Assessing their impact on the care pathway;

- Evaluating the impact and perception of innovative care technologies aimed specifically at the chronic patient.

2. Capturing the Patient Experience: Current Use and Further Opportunities

- Waiting time to receive care;

- Discharge information received;

- Support received during access to care, treatments and follow-up;

- Perceived degree of communication and cooperation from the team taking care of the patient;

- Safety concerns;

- Relations with the staff;

- Awareness on part of the medical practitioner about a patient admitted to hospital and/or undergoing surgery;

- Involvement in care pathway decisions;

- Being treated in an age-proper way (i.e., pediatric and geriatric patients);

- Being encouraged to ask;

- Being listened carefully;

- Clarity of information received;

- Kindness and courtesy;

- Adequacy of the healthcare environment (i.e., silence);

- Possibility to ask questions before subscribing informed consent.

3. Potential Benefits of PREMs in CCM

- The direction of a clinical manager, be it the general practitioner for monopathological, non-complex patients or a specialist physician with expertise on the prevailing condition in more critical, frequently hospitalized patients, ensuring the coordination of multiple treatments from a medical perspective;

- The coordination of a case manager, be a nurse or another non-medical care professional (i.e., the physical therapist for musculoskeletal conditions) who works as the reference point for the patient and eventual care giver, booking visits, prescribing drugs, renovating routine referrals, monitoring ordinary parameters, ensuring the connection of units from an organizational perspective (including, for example, the provision of social support);

- The provision of all necessary treatments from a care manager, either directly or indirectly (i.e., purchasing services from other providers). The more gravity and complexity of the patient, the greater the possibility that the care manager is part of a hospital network; the lower the severity and complexity, the greater the possibility that the care manager is a primary care provider (i.e., a general practitioners outpatient clinic). If clinical managers and case managers are flesh-and-bone professionals, the care manager represents the formal institution they work for.

- Accessibility of the technology in the area (proximity of adequate rehabilitation facilities to the hospital where surgery was performed);

- Accessibility of the treatment to protected citizens, such as frail elderly and disabled patients;

- Accessibility of the technology to all patient categories, including those affected by severe comorbidities;

- Accessibility to post-discharge facilities;

- Post-discharge facility decision is shared with the patient;

- Potential impact in reducing waiting lists;

- General inclusivity;

- The technology respects the cultural, moral and religious identity of the patient.

- Ability to safeguard the patient’s autonomy;

- Economic accessibility to the patient;

- Removal of the disease-related social costs in charge of the patient;

- (Impact of) Social determinants of compliance and technology comprehension;

- Patient satisfaction;

- Ability to improve the patient’s quality of life (of the patient);

- Ability to improve function (perceived);

- Ability to improve the family caregiver’s quality of life;

- Reduced time spent in the healthcare environment.

- Need to regulate the technology (local or national guidelines);

- Regulatory protection of specific patients;

- Is patient-information about the technology exhaustive?

- Degree of sensitive data protection;

- Safety criteria.

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weldring, T.; Smith, S.M.S. Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). Health Serv. Insights 2013, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Black, N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013, 346, f167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- European Commission. Non-Communicable Diseases. 2020. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/glossary-item/non-communicable-diseases_en#:~:text=The%204%20main%20types%20of%20noncommunicable%20diseases%20are,chronic%20obstructive%20pulmonary%20disease%20and%20asthma%29%20and%20diabetes (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Ministry of Health. Piano Nazionale della Cronicità. 2016. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2584_allegato.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Lawless, M.T.; Marshall, A.; Mittinty, M.M.; Harvey, G. What does integrated care mean from an older person’s perspective? A scoping review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jani, A.; Liyanage, H.; Hoang, U.; Moore, L.; Ferreira, F.; Yonova, I.; Brown, V.T.; de Lusignan, S. Use and impact of social prescribing: A mixed-methods feasibility study protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennestrì, F. Mind the gap: L’impatto della frammentazione assistenziale sul benessere del paziente anziano, cronico e complesso. Ital. J. Health Policy 2021, 21, 80–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aboumatar, H.; Pitts, S.; Sharma, R.; Das, A.; Smith, B.M.; Day, J.; Holzhauer, K.; Yang, S.; Bass, E.B.; Bennett, W.L. Patient engagement strategies for adults with chronic conditions: An evidence map. BMC Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Riva, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Corbo, M.; Coppola, L.; Daverio, G.; Fauci, A.; Iannone, P.; Ricciardi, W.; et al. Recommandation for patient engagement promotion in care and cure for chronic conditions. Recenti Progress. Med. 2017, 108, 455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Riva, G.; Corbo, M.; Damiani, G.; Iannone, P.; Bosio, A.C.; Ricciardi, W. Italian Consensus Statement on Patient Engagement in Chronic Care: Process and Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.B. The Concentration of Health Care Expenditure and Related Expenses for Costly Medical Conditions, 2012. In Statistical Brief (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (US)) [Internet]; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service. Universal Personalised Care: Implementing the Comprehensive Model. 2019. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/universal-personalised-care-implementing-the-comprehensive-model/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Italy 2014. Raising Standards. 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/oecd-reviews-of-health-care-quality-italy-2014-9789264225428-en.htm (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Foglia, E.; Lettieri, E.; Ferrario, L.; Porazzi, E.; Garagiola, E.; Pagani, R.; Bonfanti, M.; Lazzarotti, V.; Manzini, R.; Masella, C.; et al. Technology Assessment in Hospitals: Lessons Learned From an Empirical Experiment. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2017, 33, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, G.; Lettieri, E.; Masella, C.; Merlino, L.; Strada, A.; Tringali, M. Implementation of EunetHTA Core Model in Lombardia: The VTS Framework. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2014, 30, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2021. Chapter 6. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Leys, M. Health care policy: Qualitative evidence and health technology assessment. Health Policy 2003, 65, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, E. Ethical issues in technology assessment. Conceptual categories and procedural considerations. Int. Hournal Technol. Assess. Health Care 1998, 14, 544–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukovic, V.; Favaretti, C.; Ricciardi, W.; De Waure, C. Health technology assessment evidence on E-health/M-health technologies: Evaluating the transparency and thoroughness. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2018, 34, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre. Use of Patient-Reported Outcome and Experience Measures in Patient Care and Policy. Short Report. 2018. Available online: https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/2021-11/KCE_303C_Patient_reported_outcomes_Short_Report_0.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Porter, M.E.; Larsson, S.; Lee, T.H. Standardizing Patient Outcomes Measurement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Patient-Reported Safety Indicators: Question Set and Data Collection Guidance. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Patient-reported-incident-measures-December-2019.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Regione Toscana. Indagine PREMs. Patient-Reported Experience Measures. Rilevazione Sistematica Dell’esperienza di Ricovero Ordinario Riportato dai Pazienti Adulti e Pediatrici Nella Samità Toscana. Report dei Risultati dell’Osservatorio Permanente per L’anno 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.iris.sssup.it/retrieve/handle/11382/539613/63712/Report_PREMs_2020.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Vainieri, M. Strumenti a Supporto Della Valutazione dei Percorsi Assistenziali—PROMs e PREMs. In Proceedings of the VALUTAZIONE, Audit & Feedback dei PDTAS, Web Conference, Pisa, Italy, 11 December 2020; Available online: https://www.ars.toscana.it/images/eventi/2020/PTDA/Vainieri_M._Strumenti_a_supporto_della_valutazione_dei_percorasi_assistenziali_PROMs_PREMs.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Corazza, I.; Gilmore, K.J.; Menegazzo, F.; Abols, V. Benchmarking experience to improve paediatric healthcare: Listening to the voices of families from two European Children’s University Hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosis, S.; Cerasuolo, D.; Nuti, S. Using patient-reported measures to drive change in healthcare: The experience of the digital, continuous and systematic PREMs observatory in Italy. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, S.; Noto, G.; Vola, F.; Vainieri, M. Let’s play the patients music: A new generation of performance measurement systems in healthcare. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 2252–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Defining Value in “Value-Based Healthcare”. Report of the Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Tackling Wasteful Spending on Health. 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/tackling-wasteful-spending-on-health-9789264266414-en.htm (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- National Health Services. What Are Personal Health Budgets? Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/personal-health-budgets/what-are-personal-health-budgets-phbs/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Burne, J. Radical NHS Treatment of ‘Social Prescribing’ Could See GPs Recommend Gardening, Baking and Even Singing to Fight Chronic Ailments instead of Giving You Pills. Daily Mail Online, 14 June 2022. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10912829/Radical-NHS-treatment-GPs-recommend-gardening-baking-singing-fight-ailments.html(accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Säfström, E.; Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A. Continuity and utilization of health and community care in elderly patients with heart failure before and after hospitalization. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennestrì, F.; Gaudioso, A.; Jani, A.; Bottinelli, E.; Banfi, G. Is administered competition suitable for dealing with a public health emergency? Lessons from the local healthcare system at the centre of early COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 29, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Health Publishing. The Health Benefits of Strong Relationships. 2010. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-health-benefits-of-strong-relationships (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Van Oppen, J.D.; Valderas, J.M.; Mackintosh, N.J.; Conroy, S.P. Patient-reported outcome and experience measures in geriatric emergency medicine. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 54, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, G. The inverse care law today. Lancet 2002, 360, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.T. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971, 1, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanni, F.; Foglia, E.; Pennestrì, F.; Ferrario, L.; Banfi, G. Introducing enhanced recovery after surgery in a high-volume orthopaedic hospital: A health technology assessment. BMC Health Res. 2020, 20, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pennestrì, F.; Banfi, G. The Experience of Patients in Chronic Care Management: Applications in Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Value for Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169868

Pennestrì F, Banfi G. The Experience of Patients in Chronic Care Management: Applications in Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Value for Public Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169868

Chicago/Turabian StylePennestrì, Federico, and Giuseppe Banfi. 2022. "The Experience of Patients in Chronic Care Management: Applications in Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Value for Public Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169868

APA StylePennestrì, F., & Banfi, G. (2022). The Experience of Patients in Chronic Care Management: Applications in Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Value for Public Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169868