Research and Innovation for and with Adolescent Young Carers to Influence Policy and Practice—The European Union Funded “ME-WE” Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

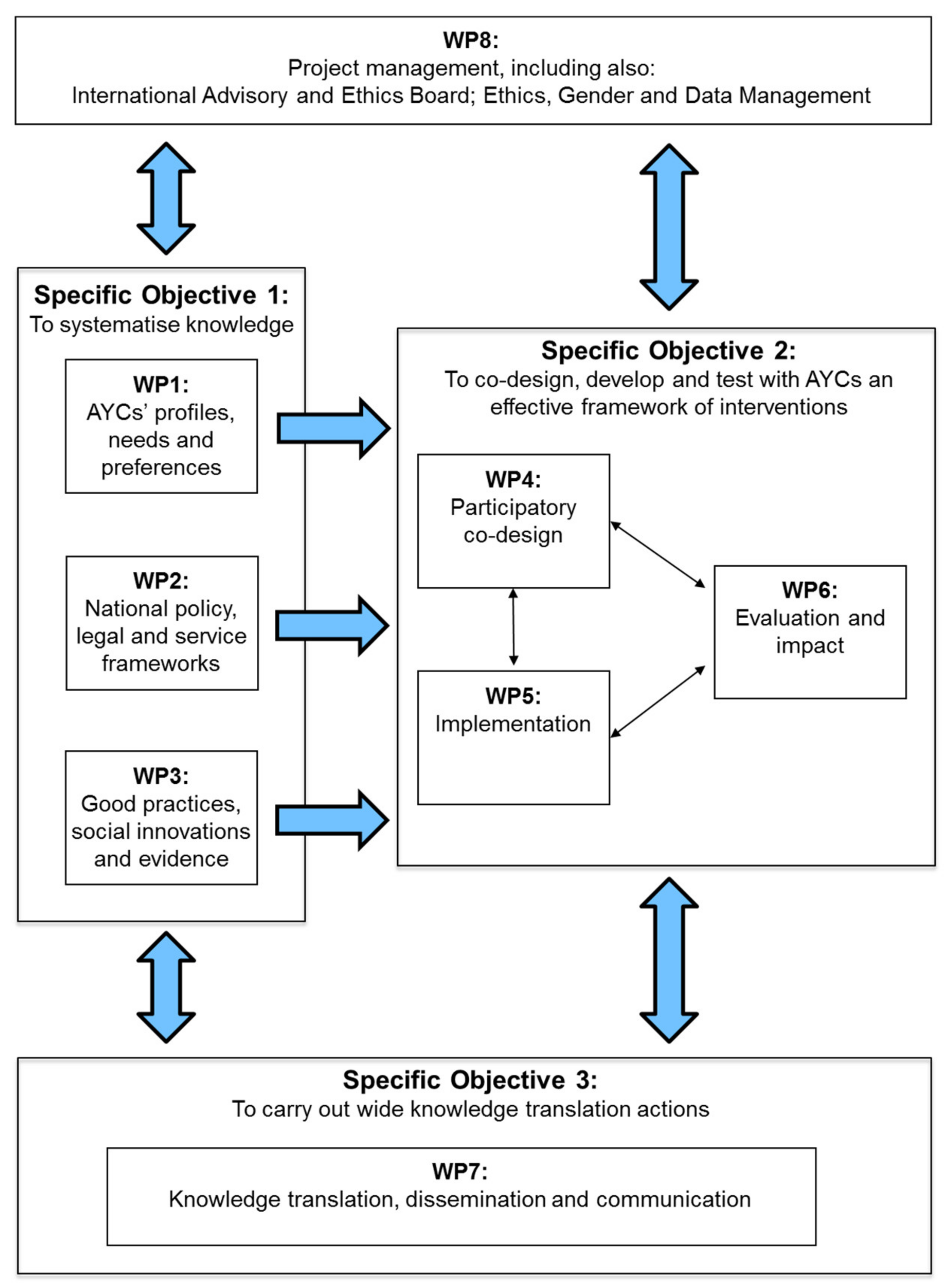

- (1)

- To systematise knowledge on AYCs by (a) identifying their profiles, needs and preferences, (b) analysing national policy, legal and service frameworks, and (c) reviewing good practices, social innovations and evidence (Work Packages, WPs, 1–3);

- (2)

- To co-design, develop and test, together with AYCs, a framework of effective and multicomponent psychosocial interventions for primary prevention focused on improving their mental health and well-being, to be tailored to each country context (WPs 4–6);

- (3)

- To carry out wide knowledge translation actions for dissemination, awareness promotion and advocacy (WP7), by spreading results among relevant stakeholders at the national, European and international levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective 1: Systematisation of Knowledge on AYCs

- (1)

- A cross-national comparative study of the profiles, needs and preferences of AYCs using an online survey (conducted in WP1). The survey was based on a structured examination of the literature and previous relevant online surveys to identify key areas of inquiry and to enable appropriate survey questions to be developed. The survey included screening questions to determine whether a person was an AYC. The following series of questions was designed with the aim of capturing responses from AYCs who might not have previously considered or thought of themselves to be an AYC:

- Q1. Do you have someone in your family with a health-related condition?

- Q2. What type of health-related condition do these persons have?

- Q3. Who are these persons (for example, parent[s], sibling[s], grandparent[s] and so on)?

- Q4. Do you live with the family members who have a health-related condition?

- Q5. Do you look after, help or support any of these family members with a health-related condition?

- A series of demographic questions;

- Impacts on Education, Employment and Support section and an open-ended qualitative question: “If you’re looking after someone, what would help support you as a carer?” A further open-ended optional question: “If you are caring for an older person (aged 65 and over), what are the main difficulties you are facing?” was asked in Italy and in Slovenia respectively, two countries characterized by a familistic welfare system where it was expected that intergenerational caring was quite common. Further information on the specific analysis of AYCs of people aged 65 and over, mainly grandparents, is published elsewhere [17,21].

- (2)

- A qualitative analysis of the development and implementation of policies, legislation and services addressing AYCs in the six partner countries (conducted in WP2). It consisted of the following:

- A preliminary examination (web-based search) for policy responses to YCs;

- Semi-structured interviews with experts in the field of AYCs and related legal provisions in all six partner countries (in total 25 interviews) to explore what specific legislation exists to protect YCs, how the legislation defines and constructs YCs, what other (non-specific) legislation can/or has been used in the context of YCs, how the procedures work in practice, their strengths and limitations, how the changes in policy and legislation were achieved and goals and hopes for the future;

- Based on both these data sources, country case study analyses were carried out to provide a rich description of how YCs are supported and protected in each country, both by the law and its enactment and with a focus on identifying the limitations and how progress was achieved;

- A cross-national synthesis of the country case study analyses was then conducted to compare the progress made in each of the partner countries which formed a report;

- Former YCs gave their feedback on the draft version of the report [22].

- (3)

- A systematic overview of successful strategies to improve AYCs’ mental health (conducted in WP3), which consisted of three sources of data as follows:

- A Delphi study with 66 experts from the six partner countries and from Austria, Belgium, Ireland and Germany who were all working in the fields of young carers, alternatively in related fields (such as youth policy), if young-carer-specific policy was not available in the country. They included researchers and policy makers together with representatives from end user organisations and industry. The eligibility of the experts was cross-checked by the national investigator teams. The experts from the additional countries were included because of their expertise of European law and policy. Interviews were held in two rounds. Three main topics were selected for the open-ended questions in the first Delphi round:

- Visibility and awareness raising of (A)YCs on a local, regional and national level;

- Current strategies, interventions and/or programmes to identify support to (A)YCs, including pros and cons;

- Future needs to support the well-being and health situation of (A)YCs;

- A systematic literature review in which 2500 papers were reviewed and reduced to 40, focused on support for YCs, together with a general literature review and social media analysis;

- A rating, ranking and consolidation task in which experts and YCs rated a selection of 39 interventions, programmes and methods identified in (a) and (b) according to criteria which included the influence of the support programme on mental health, education, resilience and transferability of the programme to an online platform/app.

2.2. Objective 2: Co-Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Intervention Framework

2.2.1. Co-Design Phase

- (1)

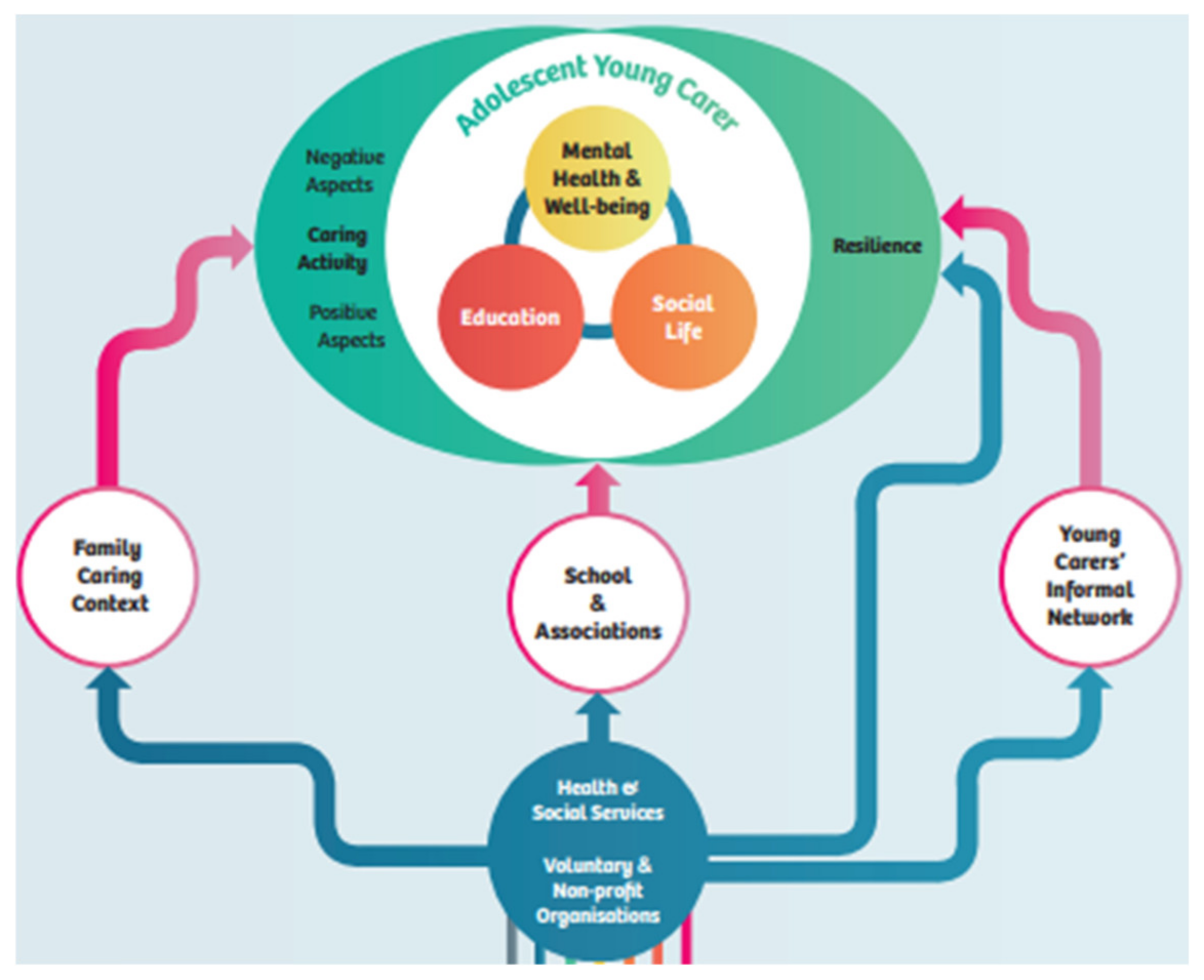

- Promoting good mental health and well-being and enhancing resilience among AYCs;

- (2)

- Enabling AYCs to recognize and accept their internal experiences;

- (3)

- Enabling AYCs to experience new or alternative behaviours and build strengths;

- (4)

- Promoting AYCs’ sense of self-worth by developing self-awareness, self-knowledge and useful self-concepts, cultivating mindfulness;

- (5)

- Enabling AYCs to build supportive social networks;

- (6)

- Enabling AYCs to be flexible in facing life events and live according to their values.

2.2.2. Implementation and Evaluation Phase

2.3. Objective 3: Implementation of Wide Knowledge Translation Actions

2.4. Ethics, Gender and Data Management Monitoring

3. Results

3.1. Systematisation of Knowledge

3.1.1. Profiles, Needs and Preferences of Respondent AYCs

3.1.2. National Policy, Service and Legal Frameworks

- (1)

- Addressing key dilemmas: firstly, whether it is acceptable to have children in a caring role? Secondly, is specific legislation/policy necessary to protect and support AYCs?

- (2)

- Further awareness and recognition of AYCs is needed. To this end, further national research work and a common definition of AYCs is required;

- (3)

- AYCs should be recognised as an important target group for policy makers and to bring this about the emphasis should be upon prevention and early interventions. Furthermore, existing legislation and policy should be extended to usefully include AYCs;

- (4)

- Involving YCs and AYCs and a range of key stakeholders in the process of campaigning for and in forming new directions in policy and practice.

3.1.3. Review of Good Practices, Social Innovations and Evidence

- (1)

- Early identification of AYCs;

- (2)

- An approach that supports YCs to build trustworthy relationships and facilitate being in a constant dialogue with friends (for peer support) and family and/or professionals which is also important to prevent loneliness and enhance coping;

- (3)

- An approach that supports respite and could promote and share activities for respite and promote online and actual offline contacts;

- (4)

- An approach that does not solely benefit the care recipient, carer or professional, but from which all parties involved benefit, for example a more family-centred approach;

- (5)

- An app can provide (indirect) access to professionals or to people whom are prior YCs who can provide both advice and emotional support and encouragement to YCs;

- (6)

- Online support that is time, place and culture independent;

- (7)

- As for point 4 in Section 3.1.2 above, co-creation of the intervention with YCs is essential.

3.2. Co-Design, Implementation and Evaluation of the Intervention Framework

3.2.1. Co-Design: National BLNs: Members and Sessions

3.2.2. Implementation and Evaluation of the Intervention Framework

Key Evaluation Results

AYCs’ Mental Health, Well-Being, Personal Confidence and Cognitive Functioning

AYCs’ Education and Employability

Impact of COVID-19 on AYCs

Testing of the ME-WE Mobile App by AYCs

ME-WE Stakeholder Core Findings

Views and Experiences of the ME-WE Intervention

- The theory and relevance of the DNA-V model (NL, IT, SE, UK), for example highlighting strengths and values in the lives of AYCs;

- Development and implementation of a targeted support intervention for AYCs in the ME-WE project (NL, CH);

- Beneficial effect on AYCs (NL, UK), because they felt seen (IT), experienced peer support (NL) and were able to learn and use new tools in practice (NL, UK, SE), and also to learn to handle emerging difficult situations due to the restrictions during the pandemic (UK);

- Positive effect of the ME-WE intervention on facilitators: acquiring new skills/knowledge that can also be used in their future work, also among other groups (UK, SI, SE), having a positive impact on personal life;

- Research assistant/facilitator (NL), and deriving a positive feeling on delivering the ME-WE groups (NL, SE);

- Support provided by the ME-WE team (IT).

- Broadening the target group of the ME-WE training (also 14 year old AYCs, and adolescents in general);

- More involvement of staff who already have a relationship with and built trust with young people, e.g., school nurses;

- More involvement of (multi-disciplinary) professionals to increase awareness, such as awareness programmes in schools, school nurses;

- A systems-/family-based approach to support AYCs;

- Ironing out the technical issues of the ME-WE app;

- Enabling AYCs to participate by facilitating a safe place during online sessions;

- A continuation plan for after the ME-WE intervention.

Awareness of AYCs

3.3. Knowledge Translation Actions (KTAs)

4. Discussion

4.1. Advances in Knowledge, Research and Innovation

4.2. Advances in Awareness, Response and Policy

4.3. Project Limitations and Challenges

4.4. Recommendations for Further Research and Action

- (1)

- Identify YCs and AYCs: Young carers have remained in the blind spot of policy makers and practitioners for too long and they need to be paid attention to. The data arising from the ME-WE study cast light for the first time on many hidden aspects of adolescent caring roles. Further studies should investigate key aspects, such as AYCs risk of self-harm or harm to others, and more detailed studies of the nature of AYCs’ mental health problems and how these impact on their past and future education/university/workforce participation, aspirations, and independent lives.

- (2)

- Recognise YCs as children in potential need of extra, tailored support: Young carers face a number of specific challenges as a result of their caregiving activities. They should therefore be approached as a group at risk and benefit from tailor-made policies and support measures.

- (3)

- Listen to YCs: No policy or practice that impacts young carers should be developed without them. This principle builds on Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, S. Young Carers. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Work; Davies, M., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- Brolin, R.; Magnusson, L.; Hanson, E. Unga Omsorgsgivare. Svensk Kartläggning—Delstudie i det Europeiska ME-WE-Projektet (Young Carers. Swedish Mapping—Sub-Study in the European ME-WE Project); Report; ME-WE Project: Kalmar, Sweden, 2022. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Condizioni di Salute e Ricorso ai Servizi Sanitari in Italia e nell’Unione Europea—Indagine EHIS 2015. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/204655 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Joseph, S.; Sempik, J.; Leu, A.; Becker, S. Young Carers Research, Practice and Policy: An Overview and Critical Perspective on Possible Future Directions. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 5, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, A.; Frech, M.; Wepf, H.; Sempik, J.; Joseph, S.; Helbling, L.; Moser, U.; Becker, S.; Jung, C. Counting Young Carers in Switzerland—A Study of Prevalence. Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tienen, I.; de Roos, S.; de Boer, A. Spijbelen onder scholieren: De rol van een zorgsituatie thuis. TSG Tijdschr. Voor Gezondh. 2020, 98, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, A.; Guggiari, E.; Phelps, D.; Magnusson, L.; Nap, H.H.; Hoefman, R.; Lewis, F.; Santini, S.; Socci, M.; Boccaletti, L.; et al. Cross-national Analysis of Legislation, Policy and Service Frameworks for Adolescent Young Carers in Europe. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.; Becker, S.; Parkhouse, T.; Joseph, S.; Hlebec, V.; Mrzel, M.; Brolin, R.; Casu, G.; Boccaletti, L.; Santini, S.; et al. The first cross-national study of adolescent young carers aged 15–17 in six European countries. Int. J. Care Caring 2022, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nap, H.H.; Hoefman, R.; de Jong, N.; Lovink, L.; Glimmerveen, L.; Lewis, F.; Santini, S.; D’Amen, B.; Socci, M.; Boccaletti, L.; et al. The awareness, visibility and support for young carers across Europe: A Delphi study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, S.; Socci, M.; D’Amen, B.; Di Rosa, M.; Casu, G.; Hlebec, V.; Lewis, F.; Leu, A.; Hoefman, R.; Brolin, R.; et al. Positive and Negative Impacts of Caring among Adolescents Caring for Grandparents. Results from an Online Survey in Six European Countries and Implications for Future Research, Policy and Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wepf, H.; Leu, A. Well-Being and Perceived Stress of Adolescent Young Carers: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 31, 934–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carers Trust. Invisible and in Distress: Prioritising the Mental Health of England’s Young Carers; Carers Trust: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hovstadius, B.; Ericson, L.; Magnusson, L. Barn Som Anhöriga: Ekonomisk Studie av Samhällets Långsiktiga Kostnader (Children as Next of Kin—An Economic Study of Society’s Long Term Costs); Nationellt Kompetenscentrum Anhöriga: Kalmar, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S.; Sempik, J. Young Adult Carers: The Impact of Caring on Health and Education. Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, A.; Becker, S. A cross-national and comparative classification of in-country awareness and policy responses to ‘young carers’. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, G.; Hlebec, V.; Boccaletti, L.; Bolko, I.; Manattini, A.; Hanson, E. Promoting Mental Health and Well-Being among Adolescent Young Carers in Europe: A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amen, B.; Socci, M.; Santini, S. Intergenerational caring: A systematic literature review on young and young adult caregivers of older people. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Becker, F.; Becker, S. Manual for Measures of Caring Activities and Outcomes for Children and Young People; Report; University of Nottingham Department of Health Care of the Elderly: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, S.; Becker, S.; Becker, F.; Regel, S. Assessment of caring and its effects in young people: Development of the Multidimensional Assessment of Caring Activities Checklist (MACA-YC18) and the Positive and Negative Outcomes of Caring Questionnaire (PANOC-YC20) for young carers. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U. The KIDSCREEN Questionnaires. Quality of Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents; Report; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, S.; D’Amen, B.; Socci, M.; Di Rosa, M.; Hanson, E.; Hlebec, V. Difficulties and Needs of Adolescent Young Caregivers of Grandparents in Italy and Slovenia: A Concurrent Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, A.; Phelps, D.; Guggiari, E.; Berger, F.; Wirth, A.; Selling, J.; Abegg, A.; Mittmasser, C.; Bocaletti, L.; Milianta, S.; et al. D2.1 Final Report on Case Study Analysis of Policy, Legal and Service Frameworks in Six Countries; ME-WE Project: Kalmar, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nap, H.H.; de Jong, N.; Lovink, L.; Glimmerveen, L.; van den Boogaard, M.; Wieringa, A.; Hoefman, R.; Lewis, F.; Santini, S.; D’Amen, B.; et al. D3.1 Consolidated Strategy and Theory Report; ME-WE Project: Kalmar, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, E.; Magnusson, L.; Sennemark, E. Blended Learning Networks Supported by Information and Communication Technology: An Intervention for Knowledge Transformation Within Family Care of Older People. Gerontology 2011, 51, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.; Ciarroci, J. The Thriving Adolescent: Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Positive Psychology to Help Teens Manage Emotions, Achieve Goals, and Build Connection; Context Press, An Imprint of New Harbinger Publications, Inc.: Oakland, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, C.M.; Tucker, M.C.; Palmer, K. Emotion Regulation in Relation to Emerging Adults’ Mental Health and Delinquency: A Multi-informant Approach. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 25, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Sikes, P. ‘It’s just limboland’: Parental dementia and young people’s life courses. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 68, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.A. Improving the Comparability of Translation. In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey; Jowell, C., Roberts, R., Fitzgerald, R., Eva, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fayers, P.M.; Jordhùy, M.S.; Kaasa, S. Cluster-randomized trials. Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzing-Blau, S.; Schnepp, W. Young carers in Germany: To live on as normal as possible—A grounded theory study. BMC Nurs. 2008, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.A.; Lambert, W.; Baer, R.A. Psychological inflexibility in childhood and adolescence: Development and evaluation of the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth. Psychol. Assess 2008, 20, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.A.; Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T. Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychol. Assess 2011, 20, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, S.; Wold, B.; Stevenson, J.; Aaroe, L.E.; Woynarowska, B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence. A cross-national comparison of prevalence and dimensionality. Eur. J. Public Health 2001, 11, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G.; Sarason, B.R.; Shearin, E.N.; Pierce, G.R. A Brief Measure of Social Support: Practical and Theoretical Implications. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1987, 4, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebec, V.; Hanson, E. Key Findings and Implications from a Cross-Country, Mixed Methods Study of a Primary Prevention Psychosocial Intervention Targeted at Adolescent Young Carers; ME-WE Project: Kalmar, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Children and Families Act 2014. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/contents/enacted (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- The Care Act 2014. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Carers Act in Scotland. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2016/9/contents/enacted (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- The Social Services and Well-Being Act in Wales. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/anaw/2014/4/contents (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Hälso och Sjukvårdslagen (2017:30, 5 kap. 7§). Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/halso--och-sjukvardslag_sfs-2017-30 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Barbabella, F.; Hanson, E. Recruitment and Participation of Young Carers in Mental Health Research: A Cross-Country Analysis from the ME-WE Project; ME-WE Project: Kalmar, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, F.; Guggiari, E.; Wirth, A.; Phelps, D.; Leu, A. Die Sichtbarkeit und Unterstützung von Young Carers in der Schweiz. Krankenpfl. –Soins Infirm. 2020, 113, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guggiari, E.; Wirth, A.; Leu, A. Young Carers in Europe. Erfahrungen aus einem internationalen Horizon 2020 Projekt. Onkologiepflege 2021, 1, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, D.; Guggiari, E.; Leu, A. Adolescent Young Carers erreichen und unterstützen. Über die Schwierigkeit, Jugendliche während der COVID-19-Pandemie zu erreichen. Schweiz. Z. Heilpädagogik 2021, 27, 45–51. Available online: www.szh-csps.ch/z2021-12-06 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Guggiari, E.; Phelps, D.; Leu, A. Rekrutierung von «Adolescent Young Carers» in der Schweiz. Erfahrungen aus dem internationalen Horizon2020 ME-WE-Projekt. Krankenpfl. -Soins Infirm. 2022, 115, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amen, B.; Socci, M.; Di Rosa, M.; Casu, G.; Boccaletti, L.; Hanson, E.; Santini, S. Italian Adolescent Young Caregivers of Grandparents: Difficulties Experienced and Support Needed in Intergenerational Caregiving—Qualitative Findings from a European Union Funded Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child. COM/2021/142 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0142 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation Establishing a European Child Guarantee. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9106-2021-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- European Commission. European Pillar of Social Rights. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/social-summit-european-pillar-social-rights-booklet_en.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- EIGE. Gender Inequalities in Care and Consequences for the Labour Market. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-inequalities-care-and-consequences-labour-market (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- European Commission. A Union of Equality: Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025. COM(2020) 152 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0152 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- EIGE. Home-Based Formal Long-Term Care for Adults and Children with Disabilities and Older Persons—Research Note. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5999-2020-ADD-1/en/pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- European Parliament. Care Services in the EU for Improved Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2018-0352_EN.html (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- European Union. Treaty on the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012M%2FTXT (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- ENOC. Position Statement on Child Mental Health in Europe. Available online: https://www.kinderrechtencommissariaat.be/sites/default/files/bestanden/enoc-2018-statement-child-mental-health-fv.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Strategische Alliantie Jonge Mantelzorg. De Alliantie. Available online: https://www.strategischealliantiejongemantelzorg.nl/alliantie (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Vilans. Handleiding Voor Organisatoren van een Netwerkbijeenkomst. Available online: https://www.zorgvoorbeter.nl/zorgvoorbeter/media/documents/thema/mantelzorg/handleiding-voor-organiseren-netwerkbijeenkomst-jonge-mantelzorgers.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Untas, A.; Jarrige, E.; Vioulac, C.; Dorard, G. Prevalence and characteristics of adolescent young carers in France: The challenge of identification. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2367–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Roos, S.A.; De Boer, A.H.; Bot, S.M. Well-being and need for support of adolescents with a chronically ill family member. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werf, H.M.; Luttik, A.M.; de Boer, A.; Roodbol, P.F.; Paans, W. Growing up with a chronically ill family member—The impact on and support needs of young adult carers: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järkestig-Berggren, U.; Bergman, A.-S.; Eriksson, M.; Priebe, G. Young carers in Sweden—A pilot study of care activities, view of caring, and psychological well-being. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2019, 24, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordenfors, M.; Melander, C. Young Carers in Sweden—A Short Overview. Report. Nka. Available online: https://eurocarers.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Young-carers-in-Sweden_2017.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Leu, A.; Wepf, H.; Sempik, J.; Nagl-Cupal, M.; Becker, S.; Jung, C.; Frech, M. Caring in mind? Professionals’ awareness of young carers and young adult carers in Switzerland. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 2390–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Kendall, C.; Toher, D.; Sempik, J.; Holland, J.; Becker, S. Young Carers in England: Findings from the 2018 BBC Survey on the Prevalence and Nature of Caring among Young People; First online publication; Child: Care, Health and Development: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Design | Originally, a cluster-based randomised control trial (RCT) design with a two (arms) by three (times) repeated measures factorial design executed in six European countries (Italy, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom). Cluster randomization was used to minimize contamination between intervention and control arms [30]. |

| Recruitment channels | Recruitment of AYCs to the study was carried out in schools (SE, SI, CH) or geographical areas by the national project teams collaborating with relevant community-based service organisations and schools (NL, IT, UK). The country-based recruitment strategies included a range of recruitment methods, such as oral presentations in schools and youth centres, dissemination materials (brochures, posters), social media and traditional media and via referrals from health and social care professionals and school staff.Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which schools were closed and face to face support services were postponed, recruitment strategies switched to social media campaigns (SE, CH) and to email and telephone communication with relevant stakeholders. |

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

| Assessment timeline | Both the ME-WE intervention and the waitlist control group were assessed at baseline (T0), immediately post-intervention for the ME-WE intervention group or after 7 weeks for the waitlist control group (T1), and at 3 months follow-up (T2). |

| Primary outcomes |

|

| Secondary outcomes |

|

| Post-Intervention Self Assessment |

|

| Other country-dependent ad hoc questions |

|

| COVID-19 delivery items |

|

| Ad-hoc online survey for stakeholders of the ME-WE project | It aimed at identifying and examining positive and negative experiences in the clinical trial study on the effectiveness of the ME-WE interventions for AYCs. The ad-hoc survey was designed by the Linnaeus University (LNU) team and the University of Ljubljana (UL) team with support of the ME-WE country partners. It consisted of both closed-end and open-ended questions on the success factors and challenges identified by stakeholders during the phases of recruitment and implementation of the ME-WE support intervention. Data were also collected to explore the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on recruitment and implementation. Furthermore, the survey was designed to gather information on the impact of the ME-WE project on the work with, and the level of awareness of, AYCs amongst stakeholders. Demographic data concerning the respondents were collected (gender, year of birth, profession). The online survey could be completed using multiple devices (computer, tablet, mobile phone) with an anticipated completion time of around 5–7 min. |

| Qualitative focus group and/or individual interviews with stakeholders in all countries | An interview guide was provided by LNU covering four topics: information and recruitment, implementation, external factors and suggestions for the future. Informed consent was obtained for all participants who consisted of ME-WE stakeholders in each of the six partner countries. Background information on gender, age, level of highest education, job title, and years spent working with children and young people were collected for all the participants. |

| Total Respondents | No. of 15–17 Year Old Respondents | No. of AYCs | No. of Male AYCs | No. of Female AYCs | No. of Transgender AYCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 981 | 893 | 214 | 67 | 141 | 1 |

| Netherlands | 719 | 630 | 199 | 48 | 141 | 3 |

| Slovenia | 1122 | 1013 | 342 | 34 | 298 | 1 |

| Sweden | 3414 | 3015 | 702 | 238 | 447 | 2 |

| Switzerland | 2343 | 871 | 240 | 45 | 193 | 0 |

| UK | 859 | 724 | 402 | 126 | 256 | 8 |

| Total | 9437 | 7146 | 2099 | 558 | 1476 | 15 |

| Mother | Father | Grandmother | Grandfather | Sister | Brother | Friend | Partner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 18 (12.9%) | 15 (10.7%) | 68 (48.6%) | 34 (24.3%) | 7 (5.0%) | 13 (9.3%) | 84 (81.6%) | 7 (6.8%) |

| Netherlands | 70 (44.6%) | 40 (25.5%) | 19 (12.1%) | 12 (7.6%) | 24 (15.3%) | 46 (29.3%) | 62 (83.8%) | 9 (12.2%) |

| Slovenia | 81 (32.9%) | 72 (29.3%) | 69 (28.0%) | 45 (18.3%) | 27 (11.0%) | 30 (12.2%) | 124 (74.3%) | 24 (14.4%) |

| Sweden | 190 (49.6%) | 131 (34.2%) | 18 (4.7%) | 26 (6.8%) | 79 (20.6%) | 72 (18.8%) | 403 (84.8%) | 40 (8.4%) |

| Switzerland | 51 (31.7%) | 25 (15.5%) | 42 (26.1%) | 21 (13.0%) | 20 (12.4%) | 27 (16.8%) | 77 (63.6%) | 11 (9.1%) |

| UK | 183 (54.3%) | 79 (23.4%) | 26 (7.7%) | 16 (4.7%) | 75 (22.3%) | 85 (25.2%) | 138 (82.6%) | 24 (14.4%) |

| Total | 593 (41.6%) | 362 (25.4%) | 242 (17.0%) | 154 (10.8%) | 232 (16.3%) | 273 (19.2%) | 888 (80.2%) | 115 (10.4%) |

| AYCs | Non AYCs | T | Df | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 11.42 (5.38) | 8.33 (4.51) | 7.54 * | 307.83 | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| Netherlands | 12.24 (5.37) | 7.48 (3.58) | 11.35 * | 280.98 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| Slovenia | 14.22 (5.81) | 10.81 (4.62) | 9.35 * | 555.99 | <0.001 | 0.65 |

| Sweden | 10.92 (4.97) | 8.50 (4.12) | 11.46 * | 964.42 | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| Switzerland | 13.15 (5.84) | 9.66 (5.96) | 7.65 | 846 | <0.001 | 0.59 |

| UK | 14.44 (5.72) | 7.95 (4.12) | 17.41 * | 692.39 | <0.001 | 1.30 |

| Total | 12.57 (5.64) | 8.81 (4.57) | 26.73 * | 3210.93 | <0.001 | 0.73 |

| Male AYCs | Female AYCs | T | Df | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 10.59 (5.27) | 11.85 (5.41) | 1.56 | 203 | 0.121 | 0.24 |

| Netherlands | 10.15 (4.16) | 12.86 (5.22) | 3.65 * | 101 | <0.001 | 0.57 |

| Slovenia | 12.59 (6.30) | 14.46 (5.65) | 1.81 | 323 | 0.072 | 0.31 |

| Sweden | 10.74 (5.32) | 11.02 (4.79) | 0.68 | 653 | 0.494 | 0.06 |

| Switzerland | 12.93 (6.40) | 13.22 (5.75) | 0.29 | 229 | 0.774 | 0.05 |

| UK | 11.98 (3.99) | 15.64 (6.14) | 6.91 * | 372 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| Total | 11.24 (5.16) | 13.07 (5.70) | 6.80 * | 1051.11 | <0.001 | 0.34 |

| Familial Adult Working and in Receipt of Wage | Family in Receipt of Government Assistance | AYC in Receipt of Support | Family in Receipt of Support | School Awareness of Caring | Employer Awareness of Caring | Friend Awareness of Caring | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 205 (97.6%) | 50 (23.8%) | 46 (22.1%) | 58 (27.6%) | 23 (10.8%) | 10 (4.8%) | 93 (44.1%) |

| Netherlands | 169 (94.9%) | 79 (45.9%) | 39 (22.4%) | 62 (35.8%) | 52 (30.8%) | 22 (13.1%) | 107 (62.2%) |

| Slovenia | 301 (97.1%) | 67 (22%) | 42 (13.8%) | 91 (30.1%) | 43 (14.2%) | 13 (4.3%) | 134 (44.5%) |

| Sweden | 661 (96.1%) | 186 (27.2%) | 279 (41.8%) | 77 (11.4%) | 213 (31.8%) | 31 (4.7%) | 342 (51.3%) |

| Switzerland | 210 (94.6%) | 52 (24.0%) | 37 (16.8%) | 41 (18.8%) | 20 (9.1%) | 29 (13.5%) | 140 (63.6%) |

| UK | 267 (72.8%) | 236 (64.5%) | 168 (45.8%) | 165 (46.2%) | 215 (58.6%) | 36 (10.1%) | 247 (67.1%) |

| Total | 1813 (91.8%) | 670 (34.4%) | 611 (31.5%) | 494 (25.5%) | 566 (29.2%) | 141 (7.4%) | 1063 (54.8%) |

| Professional Fields | Professions/Work Title |

|---|---|

| Social and health care | Youth counsellor Field secretary Family therapist Youth nurse Psychologist |

| Schools | Teacher Student coach School social worker School link worker |

| Youth centres | Youth worker Youth worker trainee |

| Higher education | Researcher Educator |

| Decision makers and advisors | Head of unit for individual and family care Youth coordinator Coordinator informal care Head of youth centre School developer Head of student health care Head of education Didactic coordinator NHS Manager Consultant Counsellor |

| Others | NGO worker Professional text writer Publisher Fundraiser Co-founder of a caring organisation Project manager Participation worker ME-WE intervention facilitator |

| Focus | Key Themes | |

|---|---|---|

| Years 1–2 | Co-design of the intervention, including the mobile app |

|

| Year 3 | Support to the field work |

|

| Year 4 | Preliminary intervention study findings |

| Knowledge Translation Action | Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness raising | Production of 11 scientific publications, which have been published on open access journals (more planned and under development). |

|

| Organisation and participation in numerous events to raise awareness on YCs and to share the project findings. | 10,000 stakeholders reached at national/regional/local level and 3000 stakeholders at European level. | |

| Translation of research findings in layperson terms and conveyed to relevant stakeholders via non-scientific publications. | A series of Policy briefs, six country-specific (Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland and UK) and one European, conveying in layperson terms the research findings from WP1, 2 and 3 and identifying policy recommendations. Italy: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Me-We-policy-brief-Italy.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) The Netherlands: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Me-We-policy-brief-The-Netherlands.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) Slovenia: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Me-We-Policy-brief-Slovenia.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) Sweden: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Me-We-Policy-brief-Sweden.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) Switzerland: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Policy-Brief_Switzerland.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) United Kingdom: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Me-We-policy-brief-UK.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) | |

| The Manual ‘My day only starts when I finish school-Multi-stakeholders’ actions to support Young Carers’, investigating the concrete actions that can be undertaken by different stakeholders (e.g., policy makers, health and social care providers, school professionals, youth, care workers, the media and the general public) to identify, support and listen to YCs. http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/MeWe-Manual-for-stakeholders.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) | ||

| The ME-WE booklet, created by YCs for YCs, containing testimonials and tips to enable YCs to take care of themselves (while caring for another person) and to achieve their goals in life. https://me-we.eu/booklet (accessed on 12 July 2022) | ||

| A series of Briefs on methodology and evaluation, based on the findings of WP5 and WP6, six country-specific, one European: “The ME-WE Model–A co-created and scientifically tested support programme for adolescent young carers”. Italy: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IT-PB-ME-WE_v2.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) The Netherlands: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/NL-PB-ME-WE_v3.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) Slovenia: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/SL-PB-ME-WE_v3.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) Sweden: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SW-PB-ME-WE-modellen_v2.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) Switzerland: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/CH-PB-ME-WE_v2.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) United Kingdom: http://me-we.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/UK-PB-ME-WE_v3.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022) | ||

| Use of social media, sharing their messages on occasion of national days dedicated to informal carers, YCs, or on International Days (Children’s Day and Mental Health Day). | 3,000,000 stakeholders have been reached. | |

| Use of traditional media to raise awareness about YCs among the general public and to disseminate the ME-WE findings. | 16 interviews on national TV or radio were released, reaching out to millions of citizens and stakeholders. | |

| Use of new tools for sharing knowledge, good practices and experiences on YCs. | The ME-WE/young carers repository was created, an online Repository of Evidence on multidisciplinary approaches to support AYCs in Europe–available to all, populated with research, policies and laws and practices–acting as a hub where relevant stakeholders can access valuable information on YCs and get inspiration. | |

| Engagement | Development of multi-disciplinary approaches involving AYCs themselves, health and social care professionals (e.g., psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, youth workers, YCs workers) as well as education professionals (e.g., head teachers, teachers and other education employees). | More than 8000 stakeholders were reached through BLNs and other events and activities with YCs and other target groups. |

| Change of policies and practices | Promotion of changes in practices, as the ME-WE project enabled professionals to be more attentive to signals of a caring role; to offer them support or to refer them to support services available at local level; to talk about but also talk with AYCs. | |

| Increased (self)identification of YCs, thanks to the increased awareness and to the empowerment of professionals. | ||

| New partnerships working to support and identify YCs (e.g., between schools and care support centres or between social services, health care, youth centres and schools), which are still ongoing and in progress within project countries. | ||

| The support offers for YCs were strengthened, as the ME-WE intervention is an ambitious and ground-breaking support programme that is easy to replicate. | ||

| Empowerment of YCs, via their active involvement in all the project activities. AYCs played an active role in the BLNs, in the design and implementation of the ME-WE intervention and in the dissemination activities. | ||

| Influence of policies, advocating for YCs to be on policy agendas at European level (see for instance EuCa’s response–on behalf of the ME-WE consortium–to the targeted consultation on the Child Guarantee and the open consultation on the new EU Strategy for the Rights of the Child: https://eurocarers.org/contribution-of-eurocarers-to-the-european-commission-consultation-on-the-child-guarantee-advocating-for-the-inclusion-of-young-carers/, accessed on 12 July 2022) and national level (for instance, in the Netherlands, the National Alliance Young Carers, of which project partner VIL is a member, lobbied to draw attention to YCs and include them in the political agenda of the Ministry of Health: https://www.jmzpro.nl/de-alliantie/, accessed on 12 July 2022). | ||

| Partners prepared and are continuing to update country sustainability plans for ensuring that the impact of the ME-WE project will endure in the future. Sustainability plans include actions for, among other things: networking and working with YCs and stakeholders, training new facilitators and interested organisations, conducting further projects and systematic follow-ups based on the ME-WE intervention, exploiting the ME-WE mobile app, advocating and lobbying for YCs’ rights with local and national policy makers. | ||

| Topic | EU Policy Developments | Contributions by ME-WE |

|---|---|---|

| Rights of the child | The biggest achievement is in relation to the latest policy developments on children’s rights at EU level: the EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child [50] and the European Child Guarantee [51]. The goal of the Child Guarantee is to break the cycle of poverty faced by millions of children. The focus is on children in need (children from precarious households; children with a migrant background; children in institutions; and children with disabilities). The Child Guarantee acknowledges that reinforced and targeted support has to be put in place to ensure that children in need have equal opportunities in enjoying their social rights. The Child Guarantee initiative will contribute to the implementation of article 11 of the European Pillar of Social Rights, which states that “children have the right to protection from poverty. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds have the right to specific measures to enhance equal opportunities” European Commission, p.19 [52]. | The ME-WE Project partners responded to the EC consultations related to these developments and advocated for a clear inclusion of YCs in the category “children in need” (in the sub-group “children from precarious households”). Indeed, research evidence, including the ME-WE survey findings, shows that YCs are at risk of poverty and social exclusion: unless adequately supported, they may face extra challenges compared to their peers in accessing their right to education, health (including mental health), leisure activities and nutrition. The ME-WE project partners were aware that the Child Guarantee left to each Member State the possibility to identify “children in need”. Yet, as the awareness about their existence and their needs is still low across Europe, it is very likely for YCs not to be seen as a target group for intervention in the way that other at-risk groups (e.g., children with migrant backgrounds or with disabilities) are. If no explicit reference was made at EU level, YCs may have been targeted by the States where awareness and support already exist, whereas they would have continued to be invisible in other Member States and their support needs would have remained unmet. Hence, the importance of a clear reference to YCs at EU level.As a result of these advocacy efforts, the Council Recommendation establishing a European Child Guarantee includes, in the definition of children in precarious family situations, examples related to the phenomenon of young caring (living with a parent with disabilities; living in a household where there are mental health problems or long-term illness; living in a household where there is substance abuse) [51]. This is a first, important success, on which the ME-WE project partners will build their advocacy efforts at national level, for a correct implementation of the Recommendation. |

| Gender equality in caring | The distribution of care work is one of today’s most significant challenges for gender equality [53]. The unequal distribution of caring responsibilities between women and men over the lifecycle is one of the drivers of the gender employment, pay and pension gaps. Hence, closing the gender care gap is one of the objectives of the EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 [54]. Gender roles in caregiving start emerging at a very early age: girls, more often than boys, are the ones to take on the care of their relatives who are chronically ill or have disabilities, along with other household tasks [55]. “Besides adult family members, many children are involved in providing care to family members who are ill or have disabilities and this has a major impact on their quality of life, education and mental health”. [55]. | As a result of the advocacy efforts led by Eurocarers on behalf of the ME-WE consortium, YCs are explicitly mentioned in the European Parliament Report “Care services in the EU for Improved Gender Equality” [56]. In detail, the EP calls on the Commission and the Member States to undertake research on the numbers of young carers and on the impact of this role on their well-being and livelihoods and, on the basis of this research, to provide support and address the specific needs of young carers, in cooperation with NGOs and educational establishments. |

| Mental health | There is a growing momentum in the EU agenda around the topic of mental health. People’s well-being is not only a value in itself; it is a principle at the heart of the European project, as enshrined by Article 3 of the Treaty on the European Union [57]. Mental health and well-being have also an impact on inclusion, growth and sustainability. Mental ill health costs the EU an estimated 3–4% of GDP, mainly through lost productivity. Mental disorders are a leading cause of early retirement and disability pensions. Therefore, there is a growing recognition about the need for mental health to be considered and addressed throughout the policy-making process at the European and national levels. This has become even more evident after the COVID-19 pandemic, as the virus, and the policy responses to it, have intensified mental health challenges. | The project consortium, led by Eurocarers, has created a successful collaboration with the European Network of Ombudspersons for Children and presented the ME-WE project at their annual conference. As a result, the ENOC statement on child mental health, adopted at the ENOC General Assembly in 2018, includes a clear reference to YCs (a recommendation to develop support programmes for young carers to enable them to better enhance and protect their mental health) [58]. |

| Country | Contribution by ME-WE to National Policy and Practice |

|---|---|

| Sweden | In Sweden, the Swedish Family Care Competence Centre (Nka), of which ME-WE project partner Linnaeus University acts as the research partner, secured financial support from the National Board of Health and Welfare Sweden (NBHWS) for the rollout of the ME-WE Model. This work commenced in the Autumn 2021, by educating and supporting health and social care professionals, school staff and representatives from civil societies in the interested 290 municipalities and 21 regions across Sweden to implement the ME-WE intervention. The NBHWS also agreed to actively promote and disseminate the core ME-WE project results and to support further research studies relating to ME-WE in Sweden.Due to the country-specific research evidence gathered in the project, the NBHWS now recognises that approximately three quarters of all children as next of kin in Sweden are actually YCs, which in turn has facilitated the work of Nka to successfully lobby for their commissioned programme of work for the period 2021–2024 to target YCs, starting with the setting up of a national User Forum, consisting of YCs (several of whom participated in the ME-WE project), to advise the NBHWS and the Public Health Agency of Sweden. |

| Slovenia | In Slovenia, the project partner established contacts with all high schools and all student dormitories in the country, as well as with hospitals, addiction centres and organisations dealing with individuals with impairments and/or special needs. The collaboration with the NGO SONČEČ (the Cerebral Palsy Association of Slovenia), via its involvement as a member in the national BLN, has proved particularly fruitful also for the long term: the NGO is willing to implement the ME-WE intervention even after the end of the project, by incorporating it in their summer camp. |

| Switzerland | In Switzerland, the ME-WE project partner was successful in increasing awareness about YCs among professionals, by presenting the topic to students in nursing and healthcare professions, as well as by writing publications in professional journals (e.g., Krankenpflege, the largest journals for professional nursing in Switzerland), in national languages. As a result of the ME-WE project activities, a rich network of engaged and motivated organisations has been established and some stakeholders have changed their working practices in relation to identifying AYCs. For example, professionals in schools and hospitals have become more attentive to any signals of a caring role and now have this issue in mind. Furthermore, the difficulties with recruiting AYCs to the Swiss clinical trial study suggested that AYCs preferred an intervention which was less time consuming, thereby giving further support for the YCs’ “Get-togethers”, recognised by the Federal Office of Public Health as an example of best practice. |

| The Netherlands | In the Netherlands, the National Alliance Young Carer [59], of which ME-WE project partner Vilans is a member, lobbied to draw attention to young carers and include them in the political agenda of the Ministry of Health. This advocacy work resulted in young carers being part of the national social media informal care campaign entitled #Deeljezorg.Regional network meetings coordinated by a care support centre and a school that participated in the ME-WE research study facilitated discussing the topic of caregiving and ways to effectively support AYCs in a specific region. AYCs were also encouraged to participate actively in these network meetings. A handbook [60] on setting up regional meetings has been developed by the Dutch partners and made available online, so that other interested care support centres and schools can create regional partnerships. Vilans currently offers interested parties the possibility to participate in ME-WE train the trainer sessions. Two care support centres have started this process and will start to facilitate the ME-WE training for YCs in the summer 2022. |

| Italy | In Italy, ANS was invited to talk about young carers during the “Mental Health Week” 2021 promoted by the National Health Service of Modena; following this event and the awareness raised among staff and managers, the Service decided to publish a call to employ a psychologist specifically appointed to the topic of YCs.The Metropolitan City of Bologna, which was involved in the piloting phase, issued a call to set up a local network of professionals supporting informal carers. |

| UK | In the UK, a promising collaboration among schools and Carers Trust Network Partners was established. Schools in the south-east of England have remained committed to supporting Carers Trust Network Partners to identify AYCs who may benefit from their services.One Carers Trust Network Partner has been asked to join the Clinical Commissioning Group steering group focusing on the mental health of young people in schools in their area, as a result of their participation in the ME-WE project.A national Young Carers Alliance has been established bringing together service providers, policy makers, professionals, researchers, and young carers themselves, to work together to raise awareness of children, adolescent and young adult carers, and to lobby for more and better services and support for them. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hanson, E.; Barbabella, F.; Magnusson, L.; Brolin, R.; Svensson, M.; Yghemonos, S.; Hlebec, V.; Bolko, I.; Boccaletti, L.; Casu, G.; et al. Research and Innovation for and with Adolescent Young Carers to Influence Policy and Practice—The European Union Funded “ME-WE” Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169932

Hanson E, Barbabella F, Magnusson L, Brolin R, Svensson M, Yghemonos S, Hlebec V, Bolko I, Boccaletti L, Casu G, et al. Research and Innovation for and with Adolescent Young Carers to Influence Policy and Practice—The European Union Funded “ME-WE” Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169932

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanson, Elizabeth, Francesco Barbabella, Lennart Magnusson, Rosita Brolin, Miriam Svensson, Stecy Yghemonos, Valentina Hlebec, Irena Bolko, Licia Boccaletti, Giulia Casu, and et al. 2022. "Research and Innovation for and with Adolescent Young Carers to Influence Policy and Practice—The European Union Funded “ME-WE” Project" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169932

APA StyleHanson, E., Barbabella, F., Magnusson, L., Brolin, R., Svensson, M., Yghemonos, S., Hlebec, V., Bolko, I., Boccaletti, L., Casu, G., Hoefman, R., de Boer, A. H., de Roos, S., Santini, S., Socci, M., D’Amen, B., Van Zoest, F., de Jong, N., Nap, H. H., ... Becker, S. (2022). Research and Innovation for and with Adolescent Young Carers to Influence Policy and Practice—The European Union Funded “ME-WE” Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169932