Each of the three World Cafés developed a definition for a digital educational institution, a digital community, or a digital leisure club. The synthesis of these results led to an overall understanding of digital settings from the perspective of the setting members.

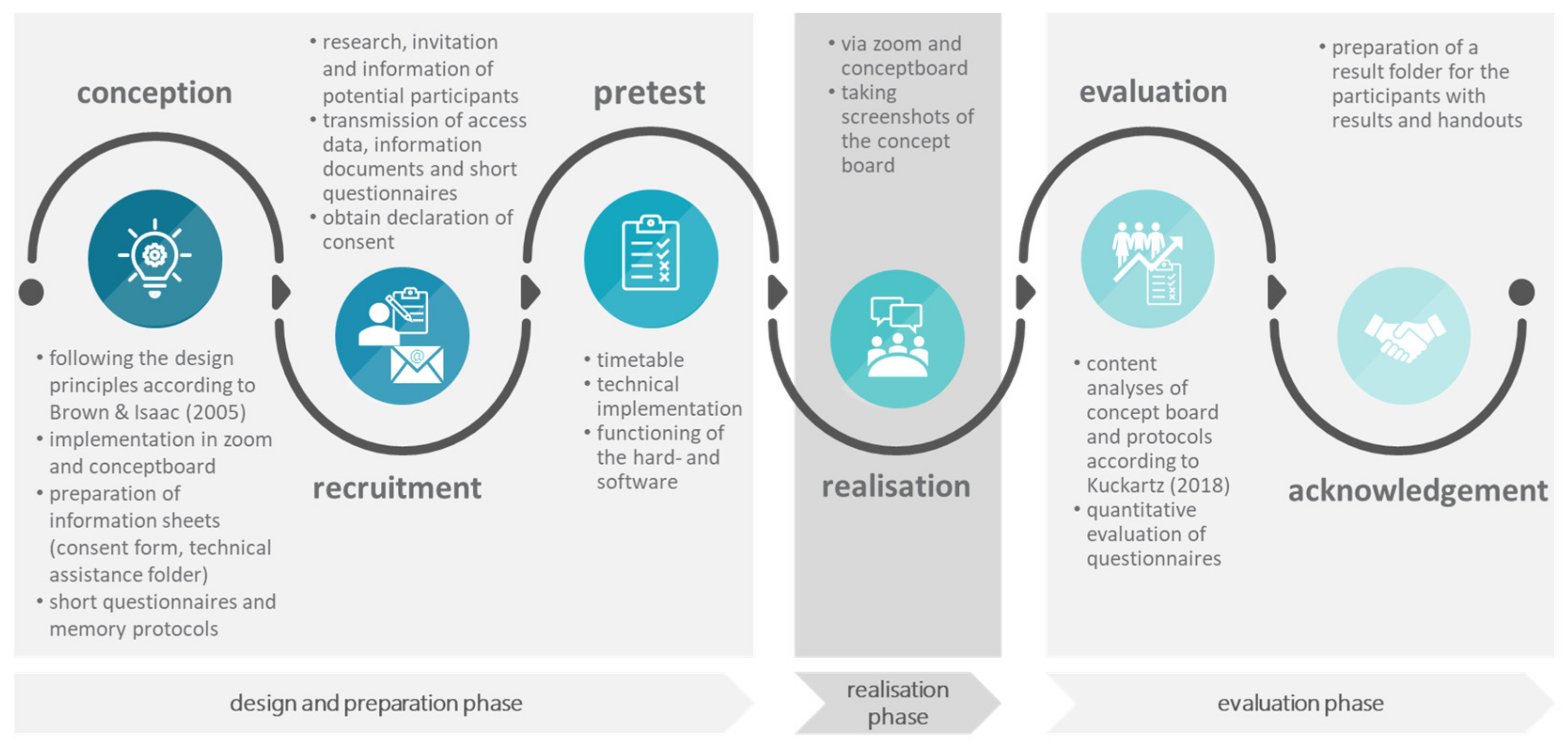

2.2. Phase 1: Design and Preparation Phase

The World Café tables were digitally illustrated via a digital pinboard. Participants were able to edit this digital pinboard and fill it with notes or other written and visual elements. To coordinate the planned discussions and the documentation of the results of the individual table rounds in small groups and the plenary, nine tiles were created on the digital pinboard (cf.

Appendix A Figure A1). The top left tile shows the World Café etiquette, which provides the basis for joint work in the World Café. The tile in the top middle shows the overall goal of the World Café, namely, finding the definition of a digital educational institution, a digital community, and a digital leisure club, respectively. The tile at the top right visualises the task for the concluding plenary discussion, aiming at aiming at synthesizing the results. All other tiles visualise the tables of the table rounds. The tiles and their contents can be enlarged by the overall café host to allow all participants to be carried along on the board simultaneously. In order to guarantee a quiet atmosphere for the small group discussions, three Zoom breakout sessions were set up in each table round. The Zoom conference room was used for the plenary discussion.

Roles: When conducting a World Café, the scientists and participants take on different roles: An overall café host or hosting team, café guests, or an individual table host. The organisers of a World Café perform the role of the overall café host. They do not act as moderators or discussion leaders to reinforce their roles as café hosts rather than traditional presenters. They listen to the group discussions by mingling without disturbing participants. They introduce the principles and café etiquette to the participants during the event and strive to ensure that the participants feel comfortable and that they always keep “the big picture” of the event in mind. The role of café guests is taken by the participants invited to the event. In addition, at the beginning or end of the small group discussion in the first table round, the café guests choose an individual table host. The chosen table hosts of each table actively participate in the discussion without acting as moderators. They stay at the same table throughout the different table rounds and welcome the new guests after each table change. Further, they give an overview of the previous conversation to build a basis and facilitate the following discussion. In each table round, all table guests help to take notes and summarise important insights. Those new to a table bring in essential ideas from their previous round and make connections to the ideas of others [

13].

In addition to the traditional roles of overall café host (OCH 1 and 2), individual table host (ITH 1, 2 and 3), and café guests, two additional roles were added for the realisation of online hosting: table observers (TO 1, 2 and 3) and technical assistant (TA). An overview of the people involved in the hosting team, their roles, and their functions are given in

Table 1.

One scientist per table took over the role of the table observer during the discussion in the small groups (Zoom breakout session) and the plenary sessions. Instead of the café host who listens to each table, as in the original method, we decided to have table observers stay at each table. In the small group discussions, which took place via Zoom in the breakout rooms, the table observers only greeted the café guests at the tables and then passed the floor to the group. The table observer, therefore, did not participate in the substantive discussion and only intervened in the group discussions if there was a conflict between the participants if the discussion did not go further, if no one participated, or if the discussion was only about individual points of views and not about a common perspective. When the table observed had to intervene, the exemplary questions and phrases provided in the World Café method were used (e.g., What is still missing from the picture? What do we not see?). In addition, the table observers observed the discussions at their table and took notes to record the course of conversation in the memory protocol after the World Café. The technical assistant took over the technical and time management of the breakout sessions, served as a contact person in case of technical problems, and navigated the participants on the digital pinboard to the respective field via the sharing function of the Conceptboard. The different conception and deviation from the original method are shown below, along with the individual design principles.

(1)

Set the context: This principle consists of explaining and defining the three key elements: purpose, participants, and parameters [

13]. First, we tried to clarify the purpose of the World Café. The relevance of a participatory definition of digital settings from the perspective of setting members was stated. Thus, it is necessary to consider the perspectives of different settings members to depict needs and requirements heterogeneously and to develop a definition corresponding to the reality of the life of those affected. The small mixed groups are suitable for allowing everyone to have their say. Linking perspectives and knowledge is a suitable way to develop a definition. The choice of the event title “Online-Café-Knowledge creates the future-tracking down digital settings” is based on the purpose of the event. The expected outcomes are the collection of essential and relevant features of digital settings, with all participants adding to their knowledge and learning from other people or perspectives.

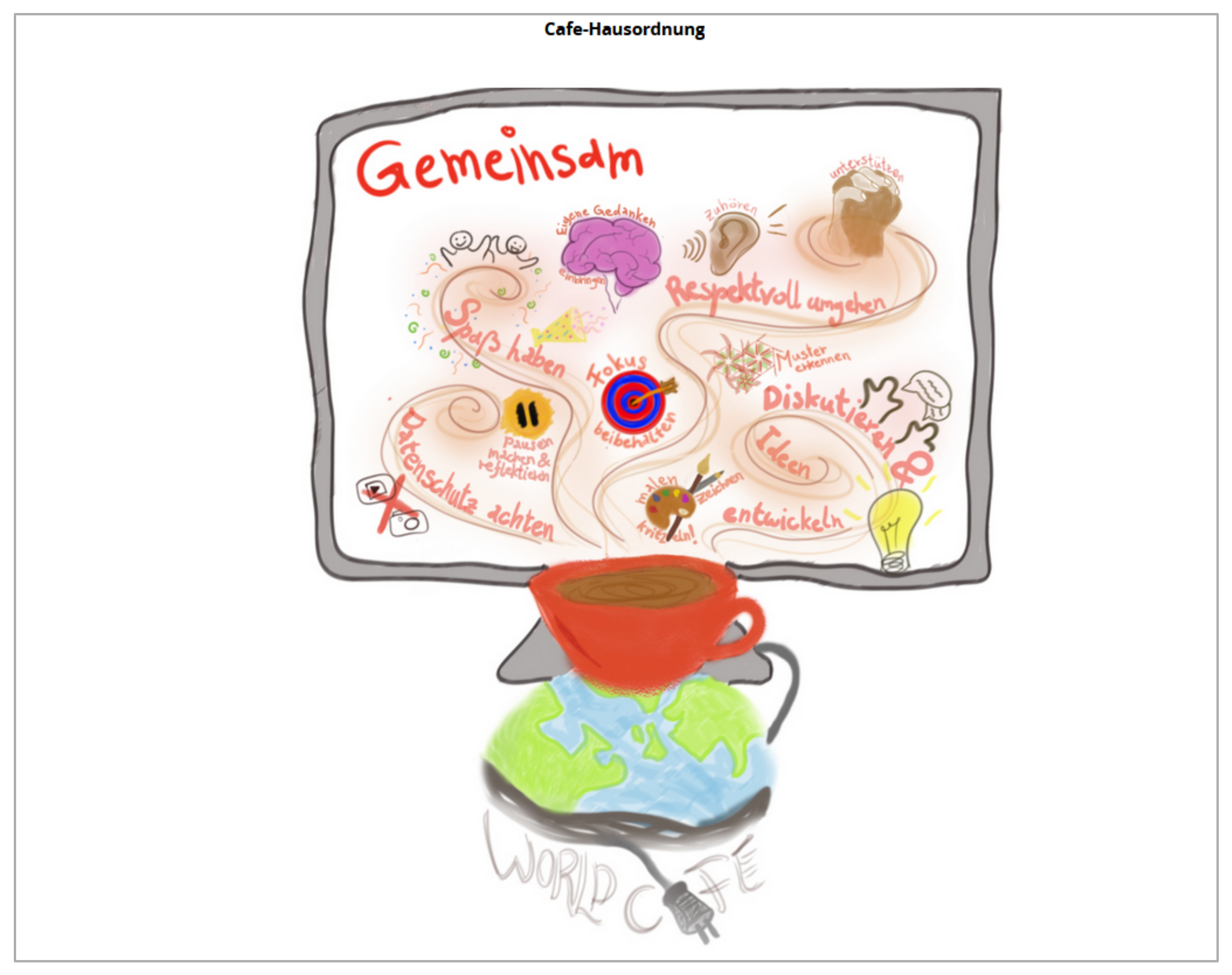

It is recommended that participants are briefed at the beginning of a World Café on the assumptions and etiquette of a World Café. This was visualised and made transparent in the digital pinboard via the café etiquette, according to Brown and Isaacs [

13] (cf.

Figure 2). The etiquette includes aspects such as “focusing on what is important”, “contributing one’s thinking and experience”, “listening to understand”, “connecting ideas”, and “looking together for patterns, insights, and deeper questions”. For the hosting of an online World Café, the aspect “respect data protection” was added to protect the personal rights of the participants. This ban is on image, sound, and video recordings [

13].

When it became clear that the World Café could only take place digitally due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, possibilities of digital hosting were considered. After selecting the Zoom and Conceptboard platforms, licences were obtained. Furthermore, it was ensured that each member of the hosting team had a digital device (computer or laptop), camera, and microphone. Information on the availability of the designated digital technologies and the planning of Zoom instruction and Zoom training for the participants of the online World Café was also planned as pre-event activities. As a post-event follow-up, the processing of the findings in the form of a summary of results was planned to offer the participants a benefit.

Furthermore, we determined the desired participants. The participants were selected to achieve a high degree of diversity. For this purpose, persons were recruited from different institutions in Germany, which can be divided into the three settings described above: educational institutions, communities, and leisure clubs. In the online World Café “educational institutions”, the secondary school, university, and adult education centre participated. Due to the online hosting and the reduced travel distances, it was possible to recruit nationwide. The online World Café “community” should be attended by various municipal institutions, e.g., the care counselling service, integration assistants, neighbourhood management, the digitisation office, and the science office. The online World Café “leisure clubs” should consist of a sports club, a senior citizens’ club, and a youth leisure club. Each World Café should involve at least five participants from each institution, so 15 participants are represented per online World Café. The members of an institution were selected from different status groups (e.g., service providers, heads of facilities, and members of a setting). Mixing the groups into small groups was aimed to guarantee the diversity of perspectives and a multi-faceted discussion. The heterogeneous distribution of characteristics was related to sex, age, and professional status (within the institution).

Recruitment was carried out via invitations by e-mail by contacting the heads of the facilities as multipliers on the one hand and the facility members directly on the other. The heads of facilities were informed about the research project and asked to invite people from their facility’s various previously defined status groups to participate in the World Café if they were interested. In addition, the contacted heads of facilities and setting members received a flyer with information about the research project, the World Café, the data protection regulations, and the further procedure. Interested persons were instructed to register for the World Café by e-mail or telephone. The project staff then selected participants. Due to a lack of response and many cancellations (due to holidays, illness, or lack of time), recruitment was expanded. Thus, other adults and senior education institutions were contacted in addition to a specific type of adult education centre (“Volkshochschule”). Recruitment from secondary schools was expanded to primary and vocational schools and private tutoring institutes. Within the community, more individual citizens from the whole city were recruited rather than focusing on a specific district. After signing the consent form, participants received a schedule for the online World Café and the access link for the Zoom meeting, preparing them for the event.

(2)

Create a hospitable space: This creates a welcoming, trusting environment where everyone feels comfortable and promotes mutual respect [

13]. Those creations already took place with the design of personal invitations for the participants. To create an inviting, trusting environment in the virtual setting as well, design elements associated with an analogue café were used for the design of the information materials, welcoming presentation, and the digital pinboard, for example, original drawings, licence-free pictures of coffee dishes, menu boards and cards, tables, and plants (cf.

Figure 3). Lounge music was also played during table changes to bridge pauses and waiting times.

During the World Café, the staff wore informal clothing. Name tags were displayed via Zoom. The intended communication at eye level was facilitated by Zoom, as all participants took the same position through the Zoom tile view. Nonetheless, the scientists’ provision of coffee and snacks was impossible due to the participants’ distance and the associated logistical challenges.

(3)

Explore questions that matter: This concept aims to draw participants’ attention to issues that matter to them and promote community engagement [

13]. Therefore, questions that matter is defining features of the World Café approach. According to Brown and Isaacs [

13], the recommendations for question development were considered in the table questions’ design by formulating open questions that are suggestion-free, encourage creativity, and aim to generate a shared perspective [

13]. To answer the overarching question, a total of four table questions per World Café (at four tables: one within the members of an institution, three mixed groups independent of the institution) were designed. Deviating from the method, the three World Cafés did not discuss exactly the same questions. The overarching question and the table questions were adapted to the focused setting in the World Café. This deviation can be justified by the heterogeneity of settings (e.g., different structures, cultures, interactions, and processes), which suggest a differentiated understanding of a digital setting.

Another modification compared to the original method was made due to the heterogeneity of the participants. To first create a shared perspective on the topic of digitalisation in their institution, an institution-internal small group discussion was held. Subsequently, three small group discussions with mixed table groups were to take place to achieve networking of ideas in the sense of the World Café method. In the three table questions, relevant components of the definition of digital setting were to be addressed individually so that an overall picture of the definition could emerge in the plenary. Relevant components of the definition were defined as elements of a digital setting, factors for the success or failure of a digital setting, and the effects of a digital setting on health and living together.

Examples of questions and tasks in the online World Café “educational institution” are shown in

Table 2. All developed questions were tested for comprehensibility and answerability in a pretest with setting members.

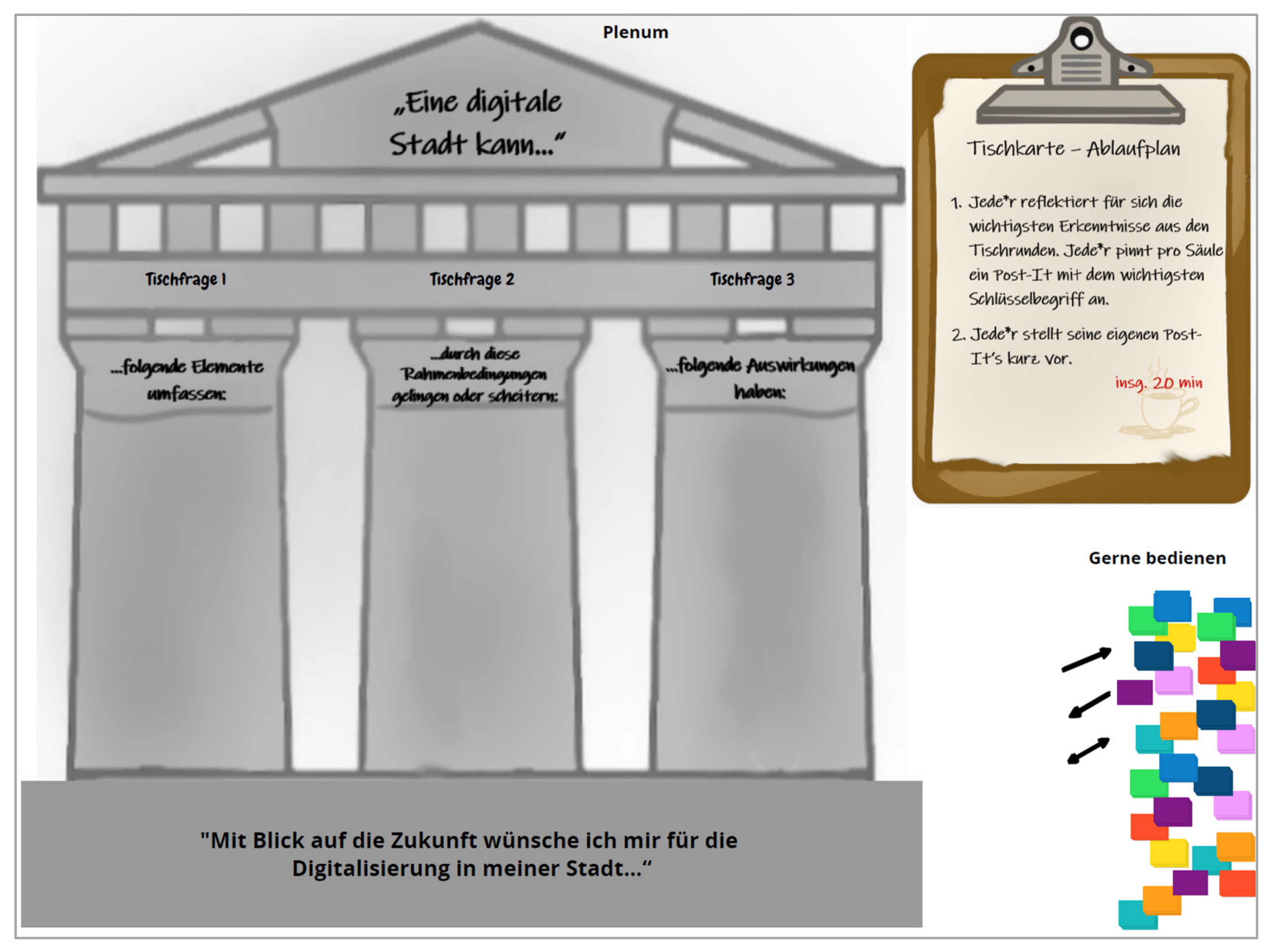

To answer the overarching question in the plenary work, a “definition house” was developed and visualised (cf.

Figure 4), containing the relevant results from the previous table rounds and the relevant components of the definition in the form of three columns. Here, the sorting and prioritisation of the table contents should take place.

The first task in the plenum was for each person to reflect on the essential findings from the table rounds. Each person pinned a Post-it with the essential key term per column. The second and third tasks were carried out for each of the three columns. Therefore, each person briefly presented their Post-its. The responsible table host led the procedure by collecting the Post-its. In the next step, the essential Post-its were prioritised using the number cards 1–3. As a final task in the plenary, the participants were asked to answer from the perspective of their role (status group), and which aspects are vital for them concerning the future in their setting.

(4)

Encourage everyone’s contribution: To create the interrelation between the “I” and the “we”, each individual is encouraged to contribute and get involved [

13]. Various actions were planned to encourage all participants to contribute and participate per the design principle. To create a low inhibition threshold for active participation, the online World Cafés were not recorded in auditory or visual form. The invitation already pointed out the requirements for successful participation, e.g., the availability of good internet quality, a digital end device, and a microphone and camera. Instructions for Zoom were also provided.

In addition, to ensure that participants can use the functions of the Conceptboard independently, a Conceptboard exercise was integrated into the first small group discussion. To inspire creativity and participation, the café etiquette included the following phases: “Play! Doodle! Draw!” and “Contribute your thinking and experience”. The table observers reminded the café guests of these principles. There was enough space on the digital tablecloth to be creative. Likewise, it was made clear that verbally and on the Conceptboard that there are no wrong answers and that all contributions have merit.

(5)

Cross-pollinate and connect diverse perspectives: It is essential to use the creative potential of living systems by purposefully increasing the diversity and interconnectedness of different perspectives while keeping the specific focus on the essential questions [

13]. According to this plan, the breakout sessions were prepared in the Zoom conference room. To achieve the networking of different perspectives, in deviation from the original method, no random mixing of the groups was aimed for, but a targeted mixing of the participants in the small group discussions was planned. The participants were designated as table hosts and so-called idea keepers and were also addressed as such verbally. The task here was to work out shared insights and not to filter out differences. For this purpose, the registered participants were noted according to institution and status group. The table groups independent of the institution were composed as heterogeneously as possible regarding status groups and institutions.

(6)

Listen together for patterns, insights, and deeper questions: According to Brown and Isaacs [

13], collective thinking is based on mutual listening, and sharing. To anchor this design principle in the online World Café, the World Café etiquette was creatively presented on a separate Conceptboard tile and introduced in the plenary (cf.

Figure 2). Likewise, the central question of the World Café was visualised to draw attention to the bigger picture continuously. All participants could therefore access the World Café etiquette at any time. Furthermore, the intended collective thinking was strengthened by the wording of the questions, which included the phrase “from our common perspective”.

(7)

Harvest and share collective discoveries: Finally, it is essential to make the jointly acquired knowledge visible in an action-oriented way [

13]. Following the principle “None of us alone knows as much as all of us together”, the online realisation of the World Café tried to offer as many different possibilities as possible for the creative documentation of the discussions. Different coloured Post-its and various arrows were made available via the Conceptboard. In addition, design functions for the Post-its such as “reduce/enlarge font size”, “change font colour” and “change font” were introduced in the Conceptboard exercise.

Compared to an analogue World Café, the digital documentation of results also changes the data basis used for evaluation. As a basis for the evaluation, screenshots of the edited digital pinboard were made. As in the analogue hosting, the digitally labelled tablecloths served as central results in the online World Café. Each table observer created memory protocols after each event to collect main contents that were not recorded on the digital pinboard or particularities in the discussion dynamics or the course of the event. Key statements and features were recorded in these. A memory protocol was particularly suitable because the table observer could concentrate entirely on conducting the conversation and observing the situation during the events. Additional contextual information can be recorded compared to an audio recording [

21].

In addition to the conception of the online World Café, a short questionnaire was developed to check and describe the heterogeneity of the participants. Focused characteristics were socio-demographic data such as age, sex, status group/professional position within the institution, focused setting, and affinity for technology. For better comparability, status groups were grouped as follows: (1) (department) heads or coordinators, (2) course or programme directors, (3) administrative staff, and (4) course or programme participants. Technology affinity is understood as a personality trait of the participant that is expressed in a person’s positive attitude, enthusiasm, and confidence towards technology [

22]. Accordingly, it maps the technical interest and acceptance of technology and positively influences the knowledge about and experience with technology. The questionnaire for recording attitudes to and use of electronic devices (TA-EG questionnaire), according to Karrer et al. [

22], was used to determine the affinity. On a total of four scales (enthusiasm for technology, competence in dealing with technology, the positive impact of technology, and negative consequences), the participants rate themselves on a five-point Likert scale for each statement [

22]. The entire short questionnaire was checked for comprehensibility and functionality in a pretest and was slightly adapted.