The Social Determinants of Adverse Childhood Experiences: An Intersectional Analysis of Place, Access to Resources, and Compounding Effects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Expanded ACEs and Historically Excluded Populations

1.3. Systemic Inequality and Co-Occurring ACEs

1.4. Contributions to the Literature

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Sample

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Limitations

3. Results

3.1. Salience of Place: Rural, Urban, and Economic Characteristics

“So, we didn’t have a social worker. And the reason that the social worker is so important is, we are in a rural area. Our poverty rate here in [County] is 43.7%. So, I have a lot of students who live in isolation. We have a lot of students that are in transit all the time. I guess they would technically fit under homelessness because they’re living with someone else, they’re here, there, they’re really hard—you know, those are the kids that are truant. Those are the kids who have health needs. So, today, this afternoon, I’ll be talking with the department of children’s services about continuing that funding for the social worker…. So, this is something that is needed, because our students who are in poverty, as you know, they’re about seven times more likely to have mental issues or be living in a home where someone has mental issues. And that connection between the classroom and that student’s parents, the caregiver, is almost nonexistent. We only have about 60% of the people here who have internet, and then they can’t afford a phone a lot of times, or if they do afford the phone, they can’t keep it on. Yeah, so the social worker has been able to reach out and go to the home, knock on the door, and say, “Hey, I’m from the school, you know, what do you need. How can we help you and how can you help us, you know, to better educate your child?” It has been a wonderful godsend having her to be able to reach out.” (Coordinated school health director in a rural, economically distressed county)

“So, we have 50 kids that are not being seen at least on school-based therapy. We try to find them places outside the school. See, here’s the issue. We need the school-based therapy. And I’m not speaking just for my school. I’m talking about school in general, because (a) there’s a transportation issue, especially in your high-poverty school districts, and (b), if parents have a car, they’re at work, and they don’t have—you know, these low-paying jobs do not offer sick days and, you know, time off and all that kind of stuff. So, parents are—cannot really take off and take the child to therapy, so—at least our Medicaid people are in that boat. And there are others, you know, insurance folks are in the same boat. I mean, we’re seeing insured kids at the school, too, but Medicaid kids are top priority. So that’s—we have got to have more focus on school-based therapy.” (Coordinated school health director in a city-adjacent county)

“The other thing that is—that we have a need for is more mental health inside the schools, and in an impoverished area like this, nobody wants to come here. We have been through five school-based mental health counselors in the last 3 years. We have a partnership with a local mental health agency, and they cannot keep someone employed inside this school. These people are getting money to go elsewhere and, you know, work in better places for more money. So, you know, it’s really impacting the kids, because we also have a very high suicide rate. For example, you know, our youngest one is 9 years old.” (Coordinated school health director in a rural, economically distressed county).

3.2. Salience of Place: Sociopolitical Context and the Culture of Care

“One of the first things I would do is call our county health department over there, which we have developed over 12 years, a very close relationship, and just like this situation here, they will give me some advice…so then the administrator will take it to their PTA or PTO to try to get some help…well, let me say we don’t turn anybody over to ICE. We do not send anything to them. We’re going to deal with the child and the family and so what we’ll do is work through translators and so forth, we do have a—we have a person who works part-time here in our offices that worked for the county many years and has many connections in the county. They will help that father try to find a job, if needed, find somewhere to live, which is a problem in our county is housing, but they will try to find them a place to live temporarily so that that parent can actually start making some money, and then we’ll monitor them to—you know, they’ll do what they need to do as far as immunizations for the child, making sure they’re in school all the time and so forth. We’ll try to help them out as much as we can, if somebody else turns them in, we can’t help that, but we will not let—We will not let—We will not let the federal government on our campuses to pick people up as their getting their child or dropping them off and that sort of thing… I had to chase them [ICE] off one of our primary’s campuses last year.” (Coordinated School Health Director in rural county)

“We are able to do so little in those [high-risk] circumstances because on that, on top of that, it’s not uncommon for the dad to be suicidal or there’s someone in the home that is abusing alcohol or dad—and we’ve had this happen—dad is HIV-positive, and we find out the baby is HIV-positive. The mom is not there, so we don’t know. But we’ve had—now what do you do? And then they don’t have a place to stay. So, I’m going to just add that more to you because this is—this is our every day. We literally have—we’ve had—in our clinic 2 weeks in a row where the mother—was the father there? The father was okay. The mother was HIV-positive, and at least two out of the three kids were HIV-positive. And they didn’t even know. And we are like—and you know, they don’t speak English, so I’m just trying to see—this is our normal. That’s our every day.”

3.3. Salience of Place: Policies That Inhibit Access to Resources and Support

“But we have a high rate of suicide and mental illness in the region, and I feel like that money should be allocated to areas that are in most need. But what I’m seeing a lot of times is, “Oh, we’re going to give it to the bigger places,” and what you have there is places that have more money, they have more resources, and then of course your impoverished areas, your small rural areas where nobody wants to come, we can’t even afford to hire anybody at this time because the money has been given to bigger places…. We need to establish funding that is more reoccurring to the district, and every district, every district on that. Last year, I was able to secure in-kind and grant funding for our district, and that is a huge help to us, especially when, you know, you’re in a really small district, and we don’t get a lot of funding anyway, especially when it’s based on [the state education funding formula]. They’re just not going to give it to us. And so, our kids—our kids do without. And probably I would think our kids have more of a need than, you know, some of the bigger schools, you know, get [funding]. You know, I know they have needs, but I doubt that their poverty rate and their mental health issues and their opioid issues here, it’s just not the same as it is here. I mean, we are in a crisis here.” (Coordinated school health director in a rural, economically distressed county)

3.4. Intergenerational Experiences of Adversity within Communities

“There is an actual poverty rate, a 27.7% … but [what] that is saying [is accepting poverty rates]—which makes me so angry because we have said to these students, to this group of youth, “Hey, what are we going to do?” That it is okay. And it’s not. I mean, now try to tell those kids that they have more worth and value than that, you know? They’re living with drug-infested homes. They’re living with all of the problems. I mean, it’s not just mothers and fathers. It’s their grandmothers and grandfathers that are doing this. I had a young man tell me the other day that, you know, he was sitting at my feet, and he said—because he calls me grandma—he said, “I have watched my grandma take [motions injecting arm]—you know, tie off and shoot up in front of me and then she would pass out.” And he said that was so scary. And he said what was even scarier, when [he] had to spend the night and all the roaches in the house. You know, this is the reality of what these kids are really living with. And the principal at [the local high school] told me at the very beginning of this, she said, “Our students can’t come in here and worry about a chemistry test or, you know, what’s going on in high school when they’re more concerned about am I going to have food? When I get out at night, who’s going to pick me up from school? Will I be allowed to ride that bus? You know, are the things going to be taken care of for me?” And so, they have no worth and value, so they step right into the paths of their parents. They’re doing—making the same mistakes. This is generational mistakes in this community.” (Director of a community anti-drug coalition in a rural, economically distressed county)

“I had a young man who was brave enough to come down and I had all this [ACEs] logic model and all of my curriculum all set up just so perfectly, and he came down, he said, “I grasp the concept of what you’re trying to do here, and it’s good,” he said, “but you’re missing the mark.” And he began to really tell me, “You know, when you live in domestic violence, when you live in abuse—an abused home, and you’re—you become a bully, and you—you know, that deals with your mental health. That starts, you know, all your mental health issues that are going on during this, you turn to drugs and alcohol. That’s how we self-medicate.” … He took the black pen and really started writing, “This leads to homelessness.” You know, he’s a foster child. He came to [this] county because he was in foster care. This is—it just makes so much sense. If you can help them to understand these issues, what led us there … it helps you understand that we don’t have to go there…. Living in these issues, when you live like that, it becomes your comfort zone, even if you don’t like it. You become comfortable in this crazy, you know, wacky environment.” (Staff member of a community-anti-drug coalition in a rural, economically distressed county)

3.5. Recognizing Additional Subpopulations and Identities

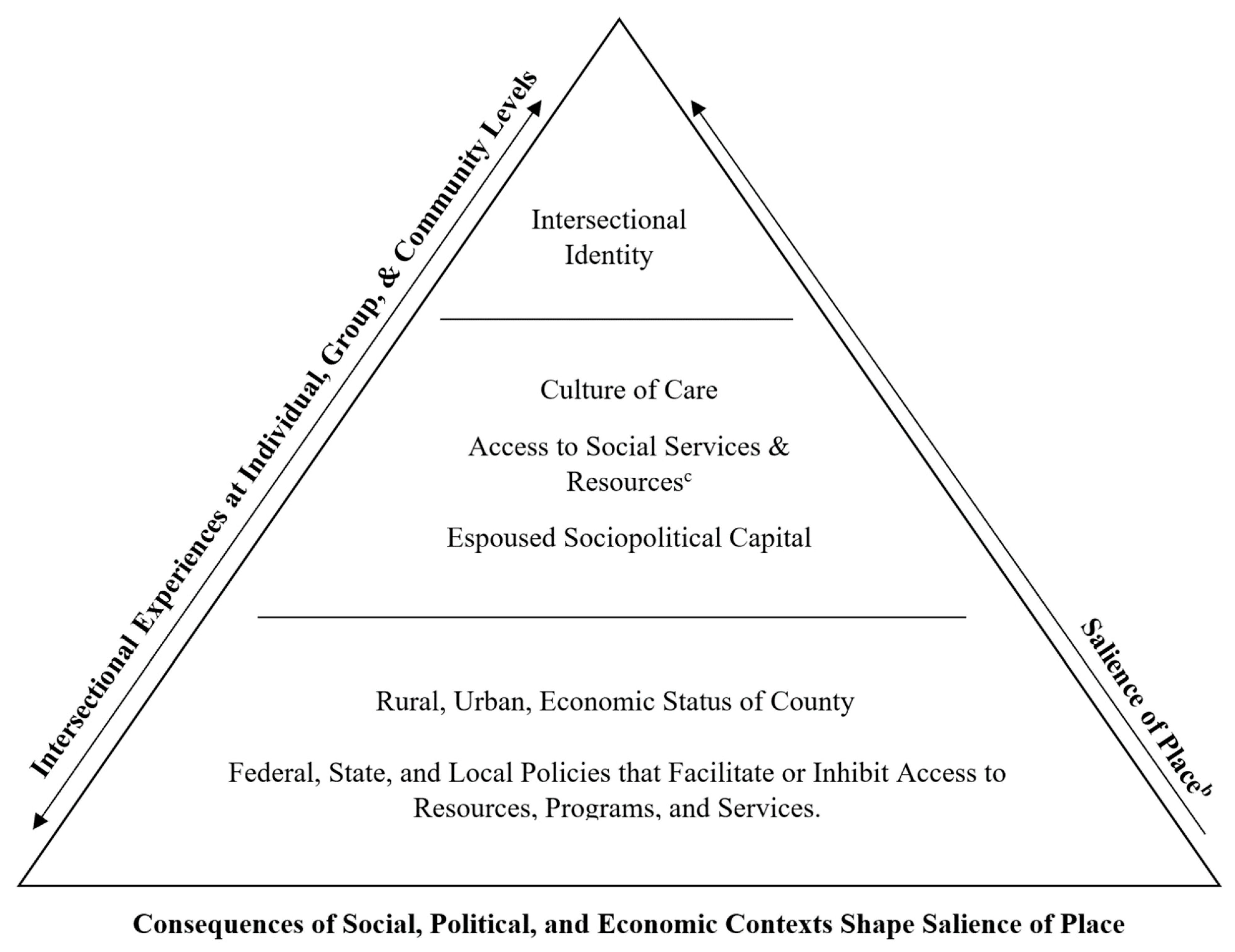

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Subpopulations at Individual, Group, and Population Identities

Appendix A.1. Individual Identities Attributed to a Child, Family Member, or Individual Living in Their Household Due to the Consequences of Social, Political and Economic Histories and the Salience of Place

- Race

- Gender

- Sexual orientation

- Religious orientation

- Socioeconomic statusIncomeAccess to reliable transportation

- Residency statusU.S. citizenUndocumented U.S. citizen (i.e., cannot afford birth certificate)Permanent residentRefugeeTemporary workplace visa (i.e., H2A visa)Undocumented person

- Immigrant country of origin

- Place of origin

- Place-based identity (Appalachian, Southern, etc.)

- New place-based identity (relocates to live with grandparent/great grandparent due to home life instability)

- Native to Tennessee

- Drug disorder

- Drug disorder family history

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipient

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipient family history

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) recipient

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) recipient family history

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) recipient

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) family history

- Incarcerated status

- Incarcerated family history

- Personal criminal record

- Active probation status

- Newly released from prison, rehabilitation, or halfway house

- Medicated Assisted Therapy recipient

- Long-term Medicated Assisted Therapy participant becomes dependent on therapy

- Church affiliation

- Health statusAcute disease statusChronic disease status (asthma, diabetes, ADD/ADHD)Mental health statusLearning disabilities

- EducationFormal educationLiteracy levelDigital literacy level

- LanguageNative English speakerNon-English speakerEnglish as a second languageEnglish as a third language, Spanish as a second language (Indigenous language is native language)

- EmploymentEmployedWorking PoorUnderemployedUnemployedExploitative work conditionsUnderserved (i.e., no access to healthcare benefits)Non-highly skilledNon-highly skilled, manual intensive laborEssential

- HousingHousedHoused without basic necessities (e.g., running water, electricity)

- Housing insecure

- Overcrowding

Transitional resident (degree of homelessness)Unhoused (homeless) - Health InsuranceInsuredUninsuredUnknown loss of insuranceExperienced insurance-gap

Appendix A.2. Family (Group) Identities That Are Part of Communities Whose Circumstances May Establish Higher-Risk Conditions for Children and Compound ACEs

- Mixed status families

- English as a second language

- Non-English speakers

- Kin Foster Parents

- Close to kin, lives in same county

- Non-kin Foster Parents

- Foster youth

- Guardian grandparents and great grandparents

- Temporary kin guardians

- Special needs guardians

- Residents of immigration raid county and perceived of being Latinx/e origin and/or undocumented

- Residents of immigration raid whose fear of being profiled prohibits their ability to drive, travel, and seek health and education support services

- Residents of distressed county

- Residents of rural county

- Residents of a high-risk geographic area (proximity to pill mill, cartel route, Appalachia, mountainous, and/or physical divide that perpetuates socioeconomic stratification, etc.)

- Residents who do not have access to a hospital or urgent care (healthcare desert)

- Women who live in healthcare deserts and do not have access to women’s healthcare

- Residents without emergency shelter services

- Residents who do not have a church affiliation and/or faith-based support system and thus have lesser access to resources and services

- Residents who experience a faith-based divide by race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, etc.

- Residents who are not in close proximity to their faith-based community and/or leadership

- Residents of a geographic area with higher concentrations of an elderly population and children population, limited employment opportunities, and shrinking middle class

- Residents of a geographic area with no public transportation

- Residents of a geographic area with no access to Lyft, Uber, or taxi services

- Residents who live in a community with high service provider turnover

- Residents without WIFI infrastructure/access

- Residents who live in homes that are not sufficiently insulated and/or are under resourced housing communities without basic services (e.g., trailer parks)

- Residents that live in homes that are overcrowded

- Residents that are part of public housing or reduced housing program

- Service providers who experience secondary trauma, burnout, and/or are not supported due to limited organizational resources and personnel

- Mandated reporters

- Halfway house residents

- Incarcerated population

- Incarcerated population without access to Medicated Assisted Therapy

- Family members with warrants

- Family members who take care of indigent family members

- Family members with special food needs (special needs baby formula, food allergies, etc.) who experience additional WIC/SNAP limitations

- Family reputation in tight knit community

- Pregnant mothers with drug disorder

- New mothers with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS) baby

- Non-involved parents/caretakers as it pertains to school

- Guardians who only have gas money to travel to-and-from work

- Elderly on fixed income or low-income status

- Elderly who experience a technological divide that constrains access to health and public services

- Elderly that cannot drive

- People who have been dropped from receiving educational and/or health services due to grant start-stop grant cycle

- People who experience stigma for seeking mental health services

- People on waiting lists for emergency and/or public services (e.g., public housing, Medicated Assisted Therapy bed, etc.)

- People who purposely get arrested to access healthcare and dental needs

- Victims of domestic violence

- Victims of natural disasters

- Populations that are more likely to be prescribed opioids

- Populations with predisposition to drugs (as described by service providers)

- Uninsured population when the child turns 18 years of age and no longer qualify for TennCare until they are 19 years of age

Appendix A.3. Group (Child) Identities Whose Familial Circumstances Linked to an Identity May Develop Higher-Risk Conditions That Worsen ACEs

- Frequent flyers (children that see the nurse on an ongoing basis because they have underlined health issues and do not have a primary care physician)

- Children separated from parent(s) due to immigration status

- Children who experienced temporary separation due to immigration status

- Children who are chronically absent from school for health-related reasons

- Children who reside in a physically isolated geographic area

- Children who are caretakers of self, siblings, and/or their parents

- Children who work and miss school to help support their parents, grandparents, etc.

- Children with no house phone and/or changing phone number

- Children who rely on free and reduced lunch for regular meals

- Children who experience food insecurity over the weekend and/or end of the month when SNAP benefits are no longer available

- Children who are transitional (coming back from a facility)

- Different-aged children and their experience and exposure to opioids

- Children living in a house of a former partner or spouse (unrelated) to the guardian

- Children living in close proximity to a registered sex offender

- Children who have bed bugs, lice, or other contagious pests in home

- Children who self-harm

- Children with disabilities

- Children with eating disorders

- Children who have suicide ideation

- Children who are on a waiting list to access services (i.e., Head Start)

- Custodial children

- Children without familial mentorship and support to meet basic child development needs

- Children with debilitating self-esteem

- Children who do not have access to transportation beyond relying on the school bus

- Children who survive a familial or peer suicide

- Children who survive familial or peer drug overdose

- Children who were dropped from the healthcare system when seeking mental health services due to service provider employment retention

- Children in the juvenile incarceration system

- Children whose parent(s) are in rehabilitation

- Children who experience drug use disorders in home

- Unhoused male children over 12 years of age (cannot stay with mother in homeless shelter facility)

- Children who suffer from neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, C. ACE, Place, Race, and Poverty: Building Hope for Children. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S123–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysar-Moon, A. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Family Social Capital, and Externalizing Behavior Problems: An Analysis Across Multiple Ecological Levels. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 0192513X2110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, B.M.; Ford, C.; Thorpe, R.J.; Bruce, M.A.; Norris, K.C. Poverty, Racism, and the Public Health Crisis in America. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 699049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockie, T.N.; Elm, J.H.L.; Walls, M.L. Examining Protective and Buffering Associations between Sociocultural Factors and Adverse Childhood Experiences among American Indian Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Quantitative, Community-Based Participatory Research Approach. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strompolis, M.; Tucker, W.; Crouch, E.; Radcliff, E. The Intersectionality of Adverse Childhood Experiences, Race/Ethnicity, and Income: Implications for Policy. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2019, 47, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, L.; Cooper, M.N.; Zubrick, S.R.; Shepherd, C.C.J. Racial Discrimination and Child and Adolescent Health in Longitudinal Studies: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 250, 112864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The Effect of Multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C.J.; Camacho, S.; Henderson, S.C.; Hernández, M.; Joshi, E. Consequences of Administrative Burden for Social Safety Nets That Support the Healthy Development of Children. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2022, 41, 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1989, 139–166. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Intersectionality as Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful. Fem. Theory 2008, 9, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCall, L. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.Y. The Transnational Journey of Intersectionality. Gend. Soc. 2012, 26, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.Y.; Ferree, M.M. Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions, and Institutions in the Study of Inequalities. Sociol. Theory 2010, 28, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstone, A. Principles of Sociological Inquiry: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods; Saylor Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferree, M.M.; Hall, E.J. Rethinking Stratification from a Feminist Perspective: Gender, Race, and Class in Mainstream Textbooks. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronholm, P.F.; Forke, C.M.; Wade, R.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Davis, M.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Fein, J.A. Adverse Childhood Experiences. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. Improving the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study Scale. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberle, A.E.; Thomas, Y.M.; Wagmiller, R.L.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S. The Impact of Neighborhood, Family, and Individual Risk Factors on Toddlers’ Disruptive Behavior. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 2046–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachter, L.M.; Coll, C.G. Racism and Child Health: A Review of the Literature and Future Directions. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, R.; Cronholm, P.F.; Fein, J.A.; Forke, C.M.; Davis, M.B.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Bair-Merritt, M.H. Household and Community-Level Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health Outcomes in a Diverse Urban Population. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 52, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E.M.; Fagan, A.A.; Pinchevsky, G.M. The Effects of Exposure to Violence and Victimization across Life Domains on Adolescent Substance Use. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxburgh, S.; MacArthur, K.R. Childhood Adversity and Adult Depression among the Incarcerated: Differential Exposure and Vulnerability by Race/Ethnicity and Gender. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfon, N.; Larson, K.; Son, J.; Lu, M.; Bethell, C. Income Inequality and the Differential Effect of Adverse Childhood Experiences in US Children. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S70–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Chuang, D.-M.; Lee, Y. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Gender, and HIV Risk Behaviors: Results from a Population-Based Sample. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haahr-Pedersen, I.; Perera, C.; Hyland, P.; Vallières, F.; Murphy, D.; Hansen, M.; Spitz, P.; Hansen, P.; Cloitre, M. Females Have More Complex Patterns of Childhood Adversity: Implications for Mental, Social, and Emotional Outcomes in Adulthood. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1708618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, P.; Ulibarri, M.; Ferraiolo, N.; Pinedo, M.; Vargas-Ojeda, A.C.; Burgos, J.L.; Ojeda, V.D. Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Depression in Latino Migrants Residing in Tijuana, Mexico. Perm. J. 2019, 23, 18–031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ports, K.A.; Lee, R.D.; Raiford, J.; Spikes, P.; Manago, C.; Wheeler, D.P. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health and Wellness Outcomes among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.; Topitzes, J.; Miller-Cribbs, J.; Brown, R.L. Influence of Race/Ethnicity and Income on the Link between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Flourishing. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.R.; Dietz, W.H. A New Framework for Addressing Adverse Childhood and Community Experiences: The Building Community Resilience Model. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S86–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory Methodology: An Overview; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam, S.; Marcellus, L.; Clark, N.; O’Mahony, J. Applying Intersectionality With Constructive Grounded Theory as an Innovative Research Approach for Studying Complex Populations: Demonstrating Congruency. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 160940691989892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Padamsee, T. Signs and Regimes: Rereading Feminist Work on Welfare States. Soc. Polit. Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2001, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham Mendez, J.; Nelson, L. Producing “Quality of Life” in the “Nuevo South”: The Spatial Dynamics of Latinos’ Social Reproduction in Southern Amenity Destinations: Producing “Quality of Life” in the “Nuevo South” . City Soc. 2016, 28, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, M. Immigrant Rights in the Nuevo South: Enforcement and Resistance at the Borderlands of Illegality. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, B. Two-Generation Pediatric Care: A Modest Proposal. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Center for Youth Wellness & ZERO to THREE. Two-Generation Approach to ACEs. 2018. Available online: https://www.acesaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/13-Two-Generation-Approach-to-ACEs-English.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

| Consequences of Social, Political, and Economic Contexts | Environment | High-Risk Conditions (Local) | High-Risk Conditions (Familial) | ACE(s) | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment loss for decades | Highest unemployment rate in the state of Tennessee | Rural, economically distressed county with prevalent food, housing, and transit insecurity | Unemployed guardians | Neglect | “Well, we were kind of used to recession and poverty because it started back in the ‘70s, okay? So, we was kind of used to that, but we didn’t really know how to evaluate and identify because we had to get ourselves trained, and that’s why it was so good when the coalition concept come in and really showed us and trained us on how to evaluate our population, and then everybody went through a decline economically for a long time. We went from where you could not get a job…. The unemployment rate at one time was up to 26%. We had the highest unemployment rate in the state. Five years in a row. Five. In the mid-2000s. Because there wasn’t a lot of opportunity here, okay? The factories wasn’t—weren’t—we’re a manufacturer type population. We’re not a highly skilled labor population, okay? So, excuse me, we went through that, then we seen the drug epidemic starting, and really, I mean, it started as a means of sustainability, people selling their medications to pay their electric bill, and a self-coping mechanism. People were using it because they were depressed. Self-medicate. So that population and the opioid population, along with the country, just became an epidemic here.” |

| Economic recession | Intergenerational poverty | Experienced poverty in home | |||

| Opioid crisis | Intergenerational drug use | Insufficient resources and services among organizations to address addiction experienced among individuals, families, and communities | Experienced drug use disorder in home | Substance use in household | |

| Measures of poverty that determine government housing programs for rural counties | High unemployment rate; intergenerational absence of workforce development | Insufficient resources and services among organizations to address prevalent food and housing insecurity | Public housing resident; government housing does not include childcare center | Sexual Abuse | We have seen some increased instances in the last couple of years at our properties [government public housing] of some instances of abuse of children, and the children weren’t school aged children. They were younger. So I had talked with—let’s maybe partner and do a training for the parents to come, and a lot of the time participation when we’d try to have types of trainings and things at the housing authority participation is generally low, and so that—We see that sometimes [childcare] as a barrier to things that we want to try to plan, because you know, we can plan all kinds of things, but we’ve tried to partner with the health department on smoking—you know, just different things … health literacy … A lot of it [child sexual abuse] has to do with substance use disorder in our community and how prevalent it is and these children get taken away in those situations a ton. That’s mainly what I would say the majority of the children come from…neglect, abuse … I would say a lot of it stems from the substance use disorder problem that we have in our community and that’s why we have a lot of those referrals … there is a lot of sexual abuse with substance abuse. A lot of the times, talking about what we were a while ago, parents trying to work and people watching the kids and they just drop them off with whoever [facilitates child sexual abuse].” |

| Economic development policies that permit disparate socioeconomic status | Most available employment opportunities are minimum wage jobs; earned wages do not meet basic needs of families | Absence of safe, affordable childcare for the working poor | Guardian and/or parent(s) need to earn a certain income amount to remain in government housing program thus ability to maintain housing security is linked to childcare | Neglect | |

| Opioid crisis | Intergenerational drug use | Insufficient resources and services among organizations to address addiction experienced among individuals, families, and communities | Childcare provider has substance use disorder | Substance abuse by caregiver |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camacho, S.; Clark Henderson, S. The Social Determinants of Adverse Childhood Experiences: An Intersectional Analysis of Place, Access to Resources, and Compounding Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710670

Camacho S, Clark Henderson S. The Social Determinants of Adverse Childhood Experiences: An Intersectional Analysis of Place, Access to Resources, and Compounding Effects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710670

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamacho, Sayil, and Sarah Clark Henderson. 2022. "The Social Determinants of Adverse Childhood Experiences: An Intersectional Analysis of Place, Access to Resources, and Compounding Effects" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710670