When Body Art Goes Awry—Severe Systemic Allergic Reaction to Red Ink Tattoo Requiring Surgical Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Clinical Presentation

2.2. Laboratory Investigations

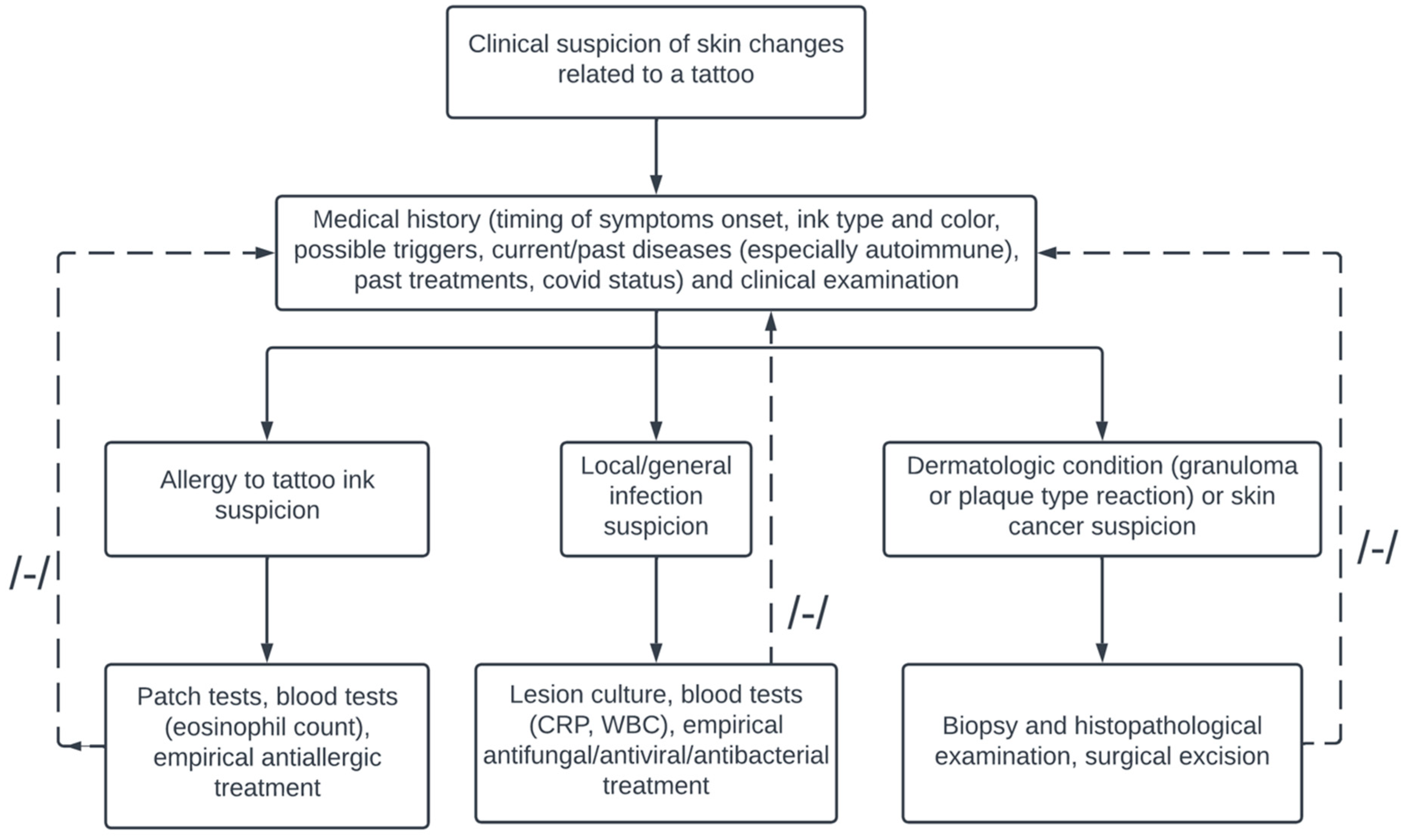

2.3. Differential Diagnosis and Clinical Course

2.4. Treatment and Interventions

2.5. Outcomes

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scatigna, M.; Masotta, V.; Cesarini, V. Sociocultural overview and predisposing factors of body art in a health promotion perspective: Survey on a sample of Italian young adults. Ann. Ig. 2022, 34, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluger, N. Cutaneous Complications Related to Tattoos: 31 Cases from Finland. Dermatology 2017, 233, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Bent, S.; Rauwerdink, D.; Oyen, E.; Maijer, K.; Rustemeyer, T.; Wolkerstorfer, A. Complications of tattoos and permanent makeup: Overview and analysis of 308 cases. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3630–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunger, N.; Molpariya, A.; Khunger, A. Complications of tattoos and tattoo removal: Stop and think before you ink. J. Cutan. Aesthetic Surg. 2015, 8, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.G.; Gold, H.; Leger, E.A.; Leger, M.C. Self-reported adverse tattoo reactions: A New York City Central Park study. Contact Dermat. 2015, 73, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, C.; Lodewick, E.; Schreiver, I.; Hesse, B.; Seim, C.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Laux, P.; Luch, A. Are metals involved in tattoo-related hypersensitivity reactions? A case report. Contact Dermat. 2017, 77, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.E.; Castanedo-Tardan, M.P.; Blyumin, M.L. Inflammation in Green (Chromium) Tattoos during Patch Testing. Dermatitis 2008, 19, E33–E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaro, A.; Tuchinda, P.; Persechino, S.; Gaspari, A. Contact Allergic Dermatitis to Gold in a Tattoo: A Case Report. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011, 24, 1111–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Villanueva, I.; Álvarez-Chinchilla, P.; Silvestre, J.F. Allergic reaction to 3 tattoo inks containing Pigment Yellow 65. Contact Dermat. 2018, 79, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.H.; Serup, J. Patients with tattoo reactions have reduced quality of life and suffer from itch: Dermatology Life Quality Index and Itch Severity Score measurements. Skin Res. Technol. 2015, 21, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.H.; Serup, J. Chronic Tattoo Reactions Cause Reduced Quality of Life Equaling Cumbersome Skin Diseases. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2015, 48, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liszewski, W.; Warshaw, E.M. Pigments in American tattoo inks and their propensity to elicit allergic contact dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serup, J. How to Diagnose and Classify Tattoo Complications in the Clinic: A System of Distinctive Patterns. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2017, 52, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serup, J. Atlas of Illustrative Cases of Tattoo Complications. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2017, 52, 139–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, I.T.; Cheung, L.W. Id reaction and allergic contact dermatitis post-picosecond laser tattoo removal: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2021, 9, 2050313X211057934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, T.R.; Ross, K.E.; Alexander, U.; Lenehan, C.E. Current knowledge of the degradation products of tattoo pigments by sunlight, laser irradiation and metabolism: A systematic review. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serup, J.; Carlsen, K.H. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: Negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermat. 2014, 71, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhie, M.L.; Ren, K.Y.; Hendry, J.M.; Molin, S.; Herzinger, T. Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity Reaction to Red Tattoo Ink Triggered by Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C: A Case Report. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2021, 13, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Kim, S.; Watsky, K.; Narayan, D. Systemic Allergic Reaction to Red Tattoo Ink Requiring Excision. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2016, 4, e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrijos, E.G.; Arpa, M.G.; Gómez, A.R.G.; Vence, M.R.; Parra, A.R.; Cañas, A.P. Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink with positive patch tests. Contact Dermat. 2021, 84, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, N.; Byrom, L. A case of multiple keratoacanthomas associated with red tattoo pigment. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2020, 61, e463–e464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badavanis, G.; Constantinou, P.; Pasmatzi, E.; Monastirli, A.; Tsambaos, D. Late-onset pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia developing within a red ink tattoo. Dermatol. Online J. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvageau, A.P.; Mojeski, J.A.; Bax, M.J.; Bogner, P.N. Delayed-onset pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia reaction to red tattoo pigment resembling squamous cell carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2019, 5, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.; Tavazoie, M.; Meehan, S.A.; Leger, M. Id reaction associated with red tattoo ink. Cutis 2018, 102, E32–E34. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.D.; Nguyen, M.; Joo, J.S.; Konia, T.H.; Tartar, D.M. Desmoplastic intradermal spitz nevi arising within red tattoo ink. Dermatol. Online J. 2018, 24, 13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.J.; Lehman, J.S.; Macon, W.R.; Sciallis, G.F. Red tattoo-related mycosis fungoides-like CD8+ pseudolymphoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2018, 45, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambier, C.; Cappel, M.A.; Wambier, S.P.D.F. Treatment of reaction to red tattoo ink with intralesional triamcinolone. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S.; Blakeway, E.; Fenn, C.; German, A.; Laws, P. A Case of Squamous Cell Carcinoma Developing within a Red-Ink Tattoo. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2017, 21, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, E.; Higgins, H.; D’Souza, L. A case of multiple squamous cell carcinomas arising from red tattoo pigment. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2017, 3, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, C.W.; Duff, G.; McKenna, D.; Regan, P.J. Malignant Melanoma Arising in Red Tattoo Ink. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2015, 42, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, M.M.; Aguinaga, F.; Grynszpan, R.; Lima, V.M.; Azulay, D.R.; Cuzzi, T.; Ramos-E-Silva, M.; Manela-Azulay, M. Granulomatous reaction to red tattoo pigment treated with allopurinol. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2015, 14, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazlouskaya, V.; Junkins-Hopkins, J.M. Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia in a Red Pigment Tattoo: A Separate Entity or Hypertrophic Lichen Planus-like Reaction? J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015, 12, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Callizo, C.; Marcoval, J.; Penín, R. Granulomatous Reactions to Red Tattoo Pigments: A Description of 5 Cases. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2015, 106, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, A.; Parodi, P.C.; Brioschi, M.; Marchesi, M.; Bruni, B.; Cangi, M.G.; Vaienti, L. Tattoo Ink-Related Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma: A Rare but Significant Complication. Case Report and Review of the Literature. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2014, 38, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, G.; Hildyard, C.A.T. Two decades later: A delayed red ink tattoo reaction. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2013201726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, S.; Jagdeo, J. Successful medical treatment of a severe reaction to red tattoo pigment. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014, 13, 1274–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Sepehri, M.; Jørgensen, B.; Serup, J. Introduction of dermatome shaving as first line treatment of chronic tattoo reactions. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2015, 26, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, R. Surgery for scar revision and reduction: From primary closure to flap surgery. Burn. Trauma 2019, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Reference | No. of Cases, Sex, Age | Clinical Appearance | Onset of Symptoms | Tattoo Site | Symptom Localization | Investigations | Treatment and Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McPhie et al. (2021) [18] | 1, M, 51 | Hyperkeratotic, erythematous nodules and raised, proliferative lesions | 14 months | Dorsum of right hand | Confined to tattoos | Biopsy reactive atypia, a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction | Clobetasol 0.05%, excision of hand nodules |

| Gómez Torrijos et al. (2021) [20] | 1, male (M), 22 | Itching, purpuric, pruritic papules | 1 month | Left forearm | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: eczema Patch tests: (+) cobalt chloride, (+) red tattoo ink in water and petrolatum | No data |

| Van Rooij et al. (2020) [21] | 1, M, 48 | Multiple squamoproliferative, erythematous lesions | 12 years | Right dorsal foot | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy eruptive keratoacanthomas Culture: (−) | Patient refused treatment |

| Badavanis et al. (2019) [22] | 1, female (F), 30 | Verruciform skin erosion, nodule | 3 years | Left ankle | Confined to tattoo | Culture: (−) X-ray of the leg (−) Biopsy: epidermal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia | Excision |

| Sauvageau et al. (2019) [23] | 1, M, 73 | Verrucous growth | 10 years | Left knee | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia | Shave removal |

| Price et al. (2018) [24] | 1, F, 40 | Pruritic, papulonodular eruptions | 1 month | Right foot, right arm | On and near red tattoos | Patch tests: (−) Biopsy: allergic contact dermatitis | Fluocinonide (topical), oral prednisone, fractional laser (ineffective), Excision and mycophenolate mofetil (effective) |

| Saunders et al. (2018) [25] | 1, F, 28 | Firm plaque and papule | About 1 year | Left arm | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: melanocytic nevus | No data |

| King et al. (2017) [26] | 1, M, 46 | Verruciform skin nodules on shin red tattoo followed by induration and itchiness of previous red forearm tattoo | 2 months | Shin and forearm | Confined to tattoos | Biopsy atypical epidermotropic infiltrate of hyperchromatic lymphocytes, variable degree of verruciform acanthosis and hyperkeratosis | Excision and intralesional steroids (effective) |

| Wambier et al. (2017) [27] | 1, F, 35 | Pruritic nodules | No data | Right leg, ankle, foot, trunk | Confined to tattoos | Lab tests (−) Biopsy: epidermal hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, chronic, lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate around ink deposits | hydroxyzine topical clobetazol 0.05%, fludroxycortide (ineffective), Intralesional tramcinolone acetate (effective) |

| Sherif et al. (2017) [28] | 1, F, 54 | Nodular, erythematous plaque | 8 years | Right lower leg | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: epidermal acanthosis and hyperkeratosis | Excision |

| Maxim et al. (2017) [29] | 1, F, 62 | 5 inflamed enlarging nodules | No data | Right calf | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: invasive squamous cell carcinoma | Excision |

| Duan et al. (2016) [19] | 1, F, 48 | Raised, ruberous, pruritic red ink tattoo area followed by widespread dermatitic eruption on trunk and extremities | 1 month | Left foot | Initially confined to tattoo, followed by systemic spread | Patch tests: (−) except for lanolin | Topical clobetasol, intralesional steroids, CO2 laser, systemic steroids (ineffective) Excision (effective) |

| Joyce et al. (2015) [30] | 1, M, 33 | Melanoma | 3 years | Chest wall | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: melanoma, CT: (−) | Excision with (+) sentinel node biopsy |

| Godinho et al. (2015) [31] | 1, F, 23 | Erythema, local edema, and pruritus | 2 years | Right ankle | Confined to tattoo | Biopsy: epithelioid granuloma | Allopurinol: recurrence 2 months after treatment |

| Kazlouskaya et al. (2015) [32] | 2: M, 45; F, 44 | Itchy eruption and verrucous lesions; pruritic nodular excoriations and pigment alterations | Many years prior with recoloring 7 months prior; several weeks | Right lateral leg; no data | Confined to tattoos | Biopsy: pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia | Topical 5-florouracil; spontaneous resolution |

| Martin-Calizo et al. (2015) [33] | 5: F, 28; F, 24; F, 23; F, 38; no data) | Erythema, inflammation; erosion; ulcer | 2 years; 4 months; 1 month; 15 days; >15 years | Right: forearm; foot; ankle; wrist; left ankle | Confined to tattoos | Biopsy: inflammatory reaction with pigment in all specimens; granuloma Culture: (−) | No data |

| Marchesi et al. (2014) [34] | 1, M, 35 | Linear reddish, nonulcerated plaques | 6 months | Right forearm | Confined to tattoo | Patch tests: (−) Biopsy: lymphoid infiltrate compatible with cutaneous pseudolymphoma Chest X-ray, lab tests: (−) | Excision (effective) |

| Chapman et al. (2014) [35] | 1, M, age not provided | Erythematous plaques | 20 years | No data | Confined to tattoos | Patient refused | Spontaneous resolution after neutropenia resolution |

| Feldstein et al. (2014) [36] | 1, F, 29 | Erythematous ulcerations with honey-colored crusting | 2 weeks | No data | Confined to tattoo | No data | Mupirocin and white petrolatum and 0.1% triamcinolone ointment: (effective) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szulia, A.; Antoszewski, B.; Zawadzki, T.; Kasielska-Trojan, A. When Body Art Goes Awry—Severe Systemic Allergic Reaction to Red Ink Tattoo Requiring Surgical Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710741

Szulia A, Antoszewski B, Zawadzki T, Kasielska-Trojan A. When Body Art Goes Awry—Severe Systemic Allergic Reaction to Red Ink Tattoo Requiring Surgical Treatment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710741

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzulia, Agata, Bogusław Antoszewski, Tomasz Zawadzki, and Anna Kasielska-Trojan. 2022. "When Body Art Goes Awry—Severe Systemic Allergic Reaction to Red Ink Tattoo Requiring Surgical Treatment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710741

APA StyleSzulia, A., Antoszewski, B., Zawadzki, T., & Kasielska-Trojan, A. (2022). When Body Art Goes Awry—Severe Systemic Allergic Reaction to Red Ink Tattoo Requiring Surgical Treatment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710741