Early Maladaptive Schemas and Self-Stigma in People with Physical Disabilities: The Role of Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

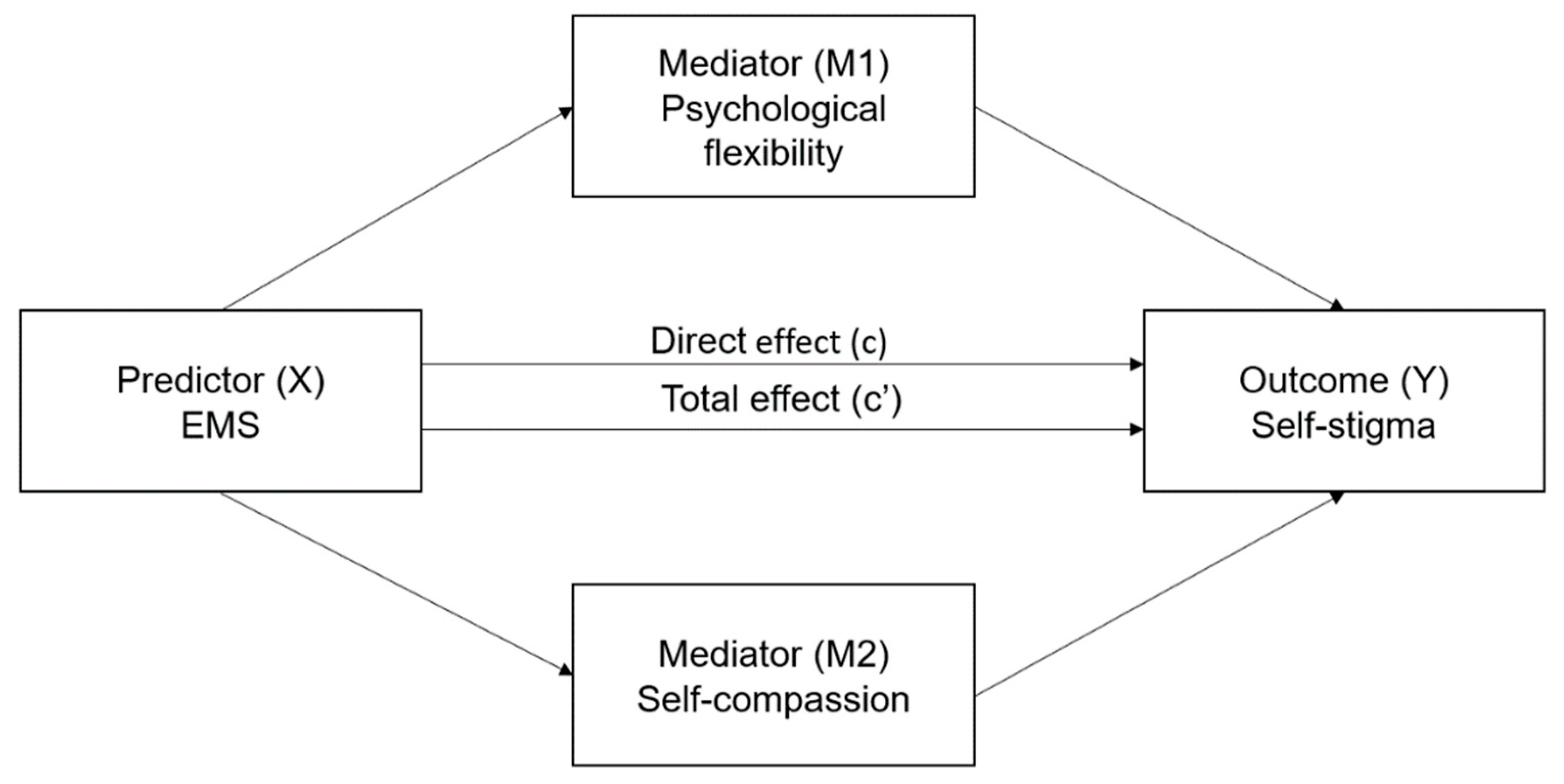

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Report on Disability. Available online: http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Loja, E.; Costa, M.E.; Hughes, B.; Menezes, I. Disability, embodiment and ableism: Stories of resistance. Disabil. Soc. 2012, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, K.R. The role of disability self-concept in adaptation to congenital or acquired disability. Rehabil. Psychol. 2014, 59, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.C.; Larson, J.E. Personal Responses to Disability Stigma: From Self-Stigma to Empowerment. Rehabil. Educ. 2006, 20, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma; Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice Hall: Engelwood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Palmer, J.; Cerri, K.; Sbarigia, U.; Chan, E.K.; Pollock, R.F.; Valentine, W.J.; Bonroy, K. Impact of Stigma on People Living with Chronic Hepatitis B. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2020, 11, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K. Self-Stigma, Bad Faith and the Experiential Self. Hum. Stud. 2019, 42, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Mak, W.W.S. Attentional Bias Associated with Habitual Self-Stigma in People with Mental Illness. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Mak, W.W.S. Poster #T43 Automatic Self-Stigma-Relevant Associations in People with Schizophrenia Experiencing Habitual Self-Stigma: Evidence from the Brief Implicit Association Tests. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 153, S304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2002, 9, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J.E.; Rendina, H.J.; Restar, A.; Ventuneac, A.; Grov, C.; Parsons, J.T. A minority stress—emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, J.B.; Platt, M.G. Shame, self-criticism, self-stigma, and compassion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 2, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, J.D.; Boyd, J.E. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, I.; Horikawa, N.; Shimotsu, S.; Hiwatashi, T.; Watanabe, M.; Okazaki, M.; Yoshimasu, H. The self-stigma of patients with epilepsy in Japan: A qualitative approach. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 109, 106994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dam, L.; Cheng, A.; Tran, P.; Wong, S.S.; Hershow, R.; Cotler, S.; Cotler, S.J. Hepatitis B Stigma and Knowledge among Vi-etnamese in Ho Chi Minh City and Chicago. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2016, 1910292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.F.; Martin, N.; Molero, F. Stigma consciousness and quality of life in persons with physical and sensory disability. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2013, 28, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Quinn, D.M. The Impact of Stigma in Healthcare on People Living with Chronic Illnesses. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 17, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Li, E.; Lok, A.S. Predictors and Barriers to Hepatitis B Screening in a Midwest Suburban Asian Population. J. Community Health 2016, 42, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Guan, M.L.; Balch, J.; Wu, E.; Rao, H.; Lin, A.; Wei, L.; Lok, A.S. Survey of hepatitis B knowledge and stigma among chronically infected patients and uninfected persons in Beijing, China. Liver Int. 2016, 36, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Peipert, A. Public- and self-stigma attached to physical versus psychological disabilities. Stigma Health 2019, 4, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.Y.; Knee, C.R.; Neighbors, C.; Zvolensky, M.J. Hacking Stigma by Loving Yourself: A Mediated-Moderation Model of Self-Compassion and Stigma. Mindfulness 2018, 10, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M.E. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide; Guilford: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart, A.; Sexton, H.; Hedley, L.M.; Wang, C.E.; Holthe, H.; Haugum, J.A.; Nordahl, H.M.; Hovland, O.J.; Holte, A. The Structure of Maladaptive Schemas: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis and a Psychometric Evaluation of Factor-Derived Scales. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2005, 29, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asmundson, G.J.G. The Science of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parcesepe, A.M.; Cabassa, L.J. Public Stigma of Mental Illness in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 40, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüsch, N.; Corrigan, P.W.; Wassel, A.; Michaels, P.; Larson, J.E.; Olschewski, M.; Wilkniss, S.; Batia, K. Self-stigma, group identification, perceived legitimacy of discrimination and mental health service use. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 551–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasko, J.; Ociskova, M.; Latalova, K.; Kamaradova, D.; Grambal, A. Psychological factors and treatment effectiveness in resistant anxiety disorders in highly comorbid inpatients. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasko, J.; Ociskova, M.; Grambal, A.; Sigmundova, Z.; Kasalova, P.; Marackova, M.; Holubova, M.; Vrbova, K.; Latalova, K.; Slepecky, M. Personality features, dissociation, self-stigma, hope, and the complex treatment of depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 2539–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ociskova, M.; Prasko, J.; Vrbova, K.; Kasalova, P.; Holubová, M.; Grambal, A.; Machu, K. Self-stigma and treatment effectiveness in patients with anxiety disorders—A mediation analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanos, P.T.; West, M.L.; Gonzales, L.; Smith, S.M.; Roe, D.; Lysaker, P.H. Change in internalized stigma and social functioning among persons diagnosed with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 1032–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.; Byrne, R.; Morrison, A.P. An Integrative Cognitive Model of Internalized Stigma in Psychosis. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2017, 45, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Borjali, A.; Bahramizadeh, H.; Eskandai, H.; Farrokhi, N.A. Psychological flexibility mediate the effect of early maladaptive schemas on Psychopathology. Int. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 3, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Lee, C.W.L.; Mak, W.W.S. Mindfulness Model of Stigma Resistance Among Individuals with Psychiatric Disorders. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Mak, W.W.S. The Differential Moderating Roles of Self-Compassion and Mindfulness in Self-Stigma and Well-Being Among People Living with Mental Illness or HIV. Mindfulness 2016, 8, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M.; Molnar, D.S.; Hirsch, J.K. Self-Compassion, Stress, and Coping in the Context of Chronic Illness. Self Identity 2015, 14, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.C.; Frankfurt, S.B.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Debeer, B.B.; Gulliver, S.B.; Morrisette, S.B. The influence of mindfulness, self-compassion, psychological flexibility, and posttraumatic stress disorder on disability and quality of life over time in war veterans. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huellemann, K.L.; Calogero, R.M. Self-compassion and Body Checking Among Women: The Mediating Role of Stigmatizing Self-perceptions. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, P.J.; Brenner, R.E.; Vogel, D.L.; Lannin, D.G.; Strass, H.A. Masculinity and barriers to seeking counseling: The buffering role of self-compassion. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasylkiw, L.; Clairo, J. Help seeking in men: When masculinity and self-compassion collide. Psychol. Men Masc. 2018, 19, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, L.R.; Tirch, D.; Leahy, R.L.; McGinn, L. Mindfulness, Psychological Flexibility and Emotional Schemas. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2012, 5, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, C.; Rickardsson, J.; Zetterqvist, V.; Simons, L.E.; Lekander, M.; Wicksell, R.K. Psychological Flexibility as a Resilience Factor in Individuals with Chronic Pain. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Levin, M.E.; Hayes, S.C. Exploring the relationship between body mass index and health-related quality of life: A pilot study of the impact of weight self-stigma and experiential avoidance. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. Confronting and Coping with Weight Stigma: An Investigation of Overweight and Obese Adults. Obesity 2006, 14, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbova, K.; Kamaradova, D.; Latalova, K.; Ociskova, M.; Prasko, J.; Mainerova, B.; Cinculova, A.; Kubinek, R.; Tichackova, A. Self-Stigma and adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders—Cross-sectional study. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 33 (Suppl. 1), s265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszkowska, A. Personality predictors of self-compassion, ego-resiliency and psychological flexibility in the context of quality of life. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 161, 109932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, A.; Chilcot, J.; Driscoll, E.; McCracken, L.M. Psychological flexibility, self-compassion and daily functioning in chronic pain. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.L.; Fiorillo, D.; Follette, V.M. Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility in a Treatment-Seeking Sample of Women Survivors of Interpersonal Violence. Violence Vict. 2018, 33, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.D.; Smout, M.F.; Delfabbro, P.H. The relationship between psychological flexibility, early maladaptive schemas, perceived parenting and psychopathology. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2016, 5, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flink, N.; Sinikallio, S.; Kuittinen, M.; Karkkola, P.; Honkalampi, K. Associations Between Early Maladaptive Schemas and Mindful Attention-Awareness. Mindfulness 2017, 9, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklósi, M.; Szabó, M.; Simon, L. The Role of Mindfulness in the Relationship Between Perceived Parenting, Early Maladaptive Schemata and Parental Sense of Competence. Mindfulness 2016, 8, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; Brasfield, H.; Anderson, S.; Stuart, G.L. The Relation between Trait Mindfulness and Early Maladaptive Schemas in Men Seeking Substance Use Treatment. Mindfulness 2014, 6, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, A.; Braehler, E.; Schmidt, R.; Löwe, B.; Häuser, W.; Zenger, M. Self-Compassion as a Resource in the Self-Stigma Process of Overweight and Obese Individuals. Obes. Facts 2015, 8, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. Young Schema Questionnaire—Short Form 3 (YSQ-S3); Cognitive Therapy Center: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oettingen, J.; Chodkiewicz, J.; Mącik, D.; Gruszczyńska, E. Polish adaptation of the Young Schema Questionnaire 3 Short Form (YSQ-S3-PL). Psychiatr. Pol. 2018, 52, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.W.S.; Cheung, R.Y.M. Self-stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: Conceptualization and unified measurement. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleszcz, B.; Dudek, J.E.; Białaszek, W.; Ostaszewski, P.; Bond, F.W. The Psychometric Properties of The Polish Version of The Acceptance And Action Questionnaire-Ii (AAQ-II). Studia Psychol. 2018, 56, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocur, D.; Flakus, M.; Fopka-Kowalczyk, M. Validity and reliability of the Polish version of the Self-Compassion Scale and its correlates. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Völckner, F. How collinearity affects mixture regression results. Mark. Lett. 2014, 26, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. The Reality Slap; Robinson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Domain/Schema | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Disconnection | |

| Emotional Deprivation | Expectation that one’s desire for a normal degree of emotional support will not be adequately met by others. |

| Emotional Inhibition | The excessive inhibition of spontaneous action, feeling or communication—usually to avoid disapproval by others, feelings of shame or losing control of one’s impulses. |

| Mistrust/Abuse | The expectation that others will hurt, abuse, humiliate, manipulate or take advantage. |

| Social Isolation | The feeling that one is isolated from the rest of the world, different from other people and/or not part of any group or community. |

| Defectiveness/Shame | The feeling that one is defective, unlovable, bad, unwanted, inferior or invalid in important respects. |

| Impaired Autonomy | |

| Subjugation | Excessive surrendering of control to others because one feels coerced—usually to avoid anger, retaliation or abandonment. |

| Dependence | Belief that one is unable to handle one’s everyday responsibilities in a competent manner, without considerable help from others (e.g., take care of oneself, solve daily problems, exercise good judgment, tackle new tasks, make good decisions). |

| Failure to Achieve | The belief that one has failed, will inevitably fail or is fundamentally inadequate relative to one’s peers, in areas of achievement (school, career, sports, etc.). |

| Vulnerability To Harm Or Illness | Exaggerated fear that imminent catastrophe (e.g., medical, emotional, external) will strike at any time and that one will be unable to prevent it. |

| Abandonment/Instability | The perceived instability or unreliability of those available for support and connection. |

| Enmeshment | Excessive emotional involvement and closeness with one or more significant others (often parents), at the expense of full individuation or normal social development. |

| Insufficient Self-control | Pervasive difficulty or refusal to exercise sufficient self-control and frustration tolerance to achieve one’s personal goals, or to restrain the excessive expression of one’s emotions and impulses. |

| Impaired Limits | |

| Entitlement | The belief that one is superior to other people, entitled to special rights and privileges, or not bound by the rules of reciprocity that guide normal social interaction. |

| Approval-Seeking | Excessive emphasis on gaining approval, recognition or attention from other people, or fitting in, at the expense of developing a secure and true sense of self. |

| Exaggerated Standards | |

| Self-Sacrifice | Excessive focus on voluntarily meeting the needs of others in daily situations, at the expense of one’s own gratification. |

| Unrelenting Standards | The underlying belief that one must strive to meet very high internalized standards of behavior and performance, usually to avoid criticism. Typically results in feelings of pressure or difficulty slowing down and in hypercriticalness toward oneself and others. |

| Pessimism | A pervasive, lifelong focus on the negative aspects of life (pain, death, loss, disappointment, conflict, guilt, resentment, unsolved problems, potential mistakes, betrayal, things that could go wrong, etc.) while minimizing or neglecting the positive or optimistic aspects. |

| Punitiveness | The belief that people should be harshly punished for making mistakes. |

| M | SD | Self-Stigma | Psychological Flexibility | Self-Compassion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disconnection | 2.46 | 1.05 | 0.43 * | −0.70 * | −0.57 * |

| Emotional Deprivation | 2.16 | 1.15 | 0.38 * | −0.52 * | −0.39 * |

| Emotional Inhibition | 2.68 | 1.25 | 0.29 * | −0.58 * | −0.50 * |

| Mistrust/Abuse | 2.67 | 1.22 | 0.30 * | −0.60 * | −0.46 * |

| Social Isolation | 2.67 | 1.36 | 0.39 * | −0.56 * | −0.50 * |

| Defectiveness/Shame | 2.11 | 1.23 | 0.45 * | −0.62 * | −0.58 * |

| Impaired Autonomy | 2.62 | 0.92 | 0.45 * | −0.71 * | −0.64 |

| Subjugation | 2.35 | 1.07 | 0.34 * | −0.63 * | −0.56 * |

| Dependence/Incompetence | 2.28 | 1.02 | 0.52 * | −0.47 * | −0.42 * |

| Failure To Achieve | 2.52 | 1.24 | 0.43 * | −0.64 * | −0.57 * |

| Vulnerability To Harm Or Illness | 2.82 | 1.27 | 0.36 * | −0.57 * | −0.49 * |

| Abandonment/Instability | 3.08 | 1.30 | 0.35 * | −0.62 * | −0.55 * |

| Enmeshment | 2.19 | 1.18 | 0.33 * | −0.40 * | −0.34 * |

| Insufficient Self-Control | 3.10 | 1.18 | 0.21 * | −0.47 * | −0.42 * |

| Impaired limits | 3.21 | 0.78 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.10 |

| Entitlement/Grandiosity | 3.07 | 0.96 | 0.13 * | −0.26 * | −0.20 * |

| Approval-Seeking | 3.34 | 1.21 | 0.15 * | −0.44 * | −0.41 * |

| Exaggerated standards | 3.20 | 0.87 | 0.39 * | −0.58 * | −0.51 * |

| Self-Sacrifice | 3.52 | 1.04 | 0.22 * | −0.25 * | −0.13 * |

| Unrelenting Standards | 3.39 | 1.07 | 0.29 * | −0.42 * | −0.40 * |

| Pessimism | 3.19 | 1.28 | 0.34 * | −0.63 * | −0.53 * |

| Punitiveness | 2.72 | 1.10 | 0.36 * | −0.46 * | −0.46 * |

| Self-stigma | 18.13 | 6.68 | - | −0.43 * | −0.36 * |

| Psychological flexibility | 31.03 | 10.35 | −0.43 * | - | 0.69 * |

| Step | Predictor | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | R2 | R2 Change | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | |||||

| 1. | 0.39 | 0.39 | 7.768 *** | ||||

| Emotional Deprivation | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.11 | ||||

| Emotional Inhibition | −0.24 | 0.44 | −0.04 | ||||

| Mistrust/Abuse | −0.77 | 0.55 | −0.14 | ||||

| Social Isolation | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.20 * | ||||

| Defectiveness/Shame | 0.89 | 0.53 | 0.16 | ||||

| Subjugation | −0.12 | 0.60 | −0.18 | ||||

| Dependence/Incompetence | 2.69 | 0.58 | 0.41 * | ||||

| Failure To Achieve | −0.30 | 0.52 | −0.06 | ||||

| Vulnerability To Harm Or Illness | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.11 | ||||

| Abandonment/Instability | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.01 | ||||

| Enmeshment | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.01 | ||||

| Insufficient Self-Control | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.01 | ||||

| Entitlement/Grandiosity | −0.06 | 0.52 | −0.01 | ||||

| Approval-Seeking | −0.44 | 0.46 | −0.08 | ||||

| Self-Sacrifice | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.05 | ||||

| Unrelenting Standards | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.12 | ||||

| Pessimism | 0.29 | 0.55 | 0.06 | ||||

| Punitiveness | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.01 | ||||

| 2. | 0.41 | 0.02 | 7.962 *** | ||||

| Emotional Deprivation | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.10 | ||||

| Emotional Inhibition | −0.38 | 0.43 | −0.07 | ||||

| Mistrust/Abuse | −0.86 | 0.54 | −0.16 | ||||

| Social Isolation | 0.99 | 0.46 | 0.20 * | ||||

| Defectiveness/Shame | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.13 | ||||

| Subjugation | −1.15 | 0.59 | −0.18 * | ||||

| Dependence/Incompetence | 2.78 | 0.57 | 0.42 * | ||||

| Failure To Achieve | −0.62 | 0.53 | −0.12 | ||||

| Vulnerability To Harm Or Illness | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.09 | ||||

| Abandonment/Instability | −0.21 | 0.45 | −0.04 | ||||

| Enmeshment | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.03 | ||||

| Insufficient Self-Control | −0.04 | 0.44 | −0.01 | ||||

| Entitlement/Grandiosity | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.01 | ||||

| Approval-Seeking | −0.50 | 0.45 | −0.09 | ||||

| Self-Sacrifice | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.05 | ||||

| Unrelenting Standards | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.09 | ||||

| Pessimism | 0.14 | 0.54 | 0.03 | ||||

| Punitiveness | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.03 | ||||

| Psychological flexibility | −0.15 | 0.06 | −0.23 * | ||||

| 3. | 0.41 | 0.00 | 7.537 *** | ||||

| Emotional Deprivation | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.10 | ||||

| Emotional Inhibition | −0.38 | 0.43 | −0.07 | ||||

| Mistrust/Abuse | −0.85 | 0.55 | −0.15 | ||||

| Social Isolation | 0.99 | 0.46 | 0.20 * | ||||

| Defectiveness/Shame | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.12 | ||||

| Subjugation | −1.16 | 0.59 | −0.18 * | ||||

| Dependence/Incompetence | 2.78 | 0.57 | 0.42 * | ||||

| Failure To Achieve | −0.63 | 0.53 | −0.12 | ||||

| Vulnerability To Harm Or Illness | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.09 | ||||

| Abandonment/Instability | −0.23 | 0.45 | −0.04 | ||||

| Enmeshment | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.03 | ||||

| Insufficient Self-Control | −0.05 | 0.44 | −0.01 | ||||

| Entitlement/Grandiosity | 0.08 | 0.51 | 0.01 | ||||

| Approval-Seeking | −0.51 | 0.45 | 0.09 | ||||

| Self-Sacrifice | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.05 | ||||

| Unrelenting Standards | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.09 | ||||

| Pessimism | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.03 | ||||

| Punitiveness | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.03 | ||||

| Psychological flexibility | −0.14 | 0.06 | −0.22 * | ||||

| Self-compassion | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.02 | ||||

| Step | Predictor | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | R2 | R2 Change | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | |||||

| 1. | 0.26 | 0.26 | 22.175 *** | ||||

| Disconnection | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.21 *** | ||||

| Impaired Autonomy | 2.05 | 0.70 | 0.28 *** | ||||

| Impaired Limits | −0.50 | 0.49 | −0.06 | ||||

| Exaggerated Standards | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.09 | ||||

| 2. | 0.28 | 0.02 | 18.395 *** | ||||

| Disconnection | 1.01 | 0.60 | 0.16 | ||||

| Impaired Autonomy | 1.66 | 0.74 | 0.23 * | ||||

| Impaired Limits | −0.41 | 0.50 | −0.05 | ||||

| Exaggerated Standards | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.08 | ||||

| Psychological flexibility | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.14 | ||||

| 3. | 0.28 | 0.00 | 15.263 *** | ||||

| Disconnection | 1.01 | 0.60 | 0.16 | ||||

| Impaired Autonomy | 1.67 | 0.75 | 0.23 * | ||||

| Impaired Limits | −0.41 | 0.50 | −0.05 | ||||

| Exaggerated Standards | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.08 | ||||

| Psychological flexibility | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.14 | ||||

| Self-compassion | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | ||||

| Model & Effects | X: Disconnection | Impaired Autonomy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Estimate | Unstandardized Effect B (SE) | 95% CI | StandardizedEstimate | Unstandardized Effect B (SE) | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Direct effect of X on Y | 0.29 | 1.85 (0.51) | 0.84 | 2.86 | 0.37 | 2.59 (0.57) | 1.48 | 3.71 |

| Total effect of X on Y | 0.47 | 3.02 (0.37) | 2.29 | 3.74 | 0.51 | 3.58 (0.39) | 2.80 | 4.36 |

| Indirect effects: | ||||||||

| Total indirect effect of X on Y | 0.18 | 1.17 (0.37) | 0.46 | 1.90 | 0.14 | 0.99 (0.43) | 0.17 | 1.85 |

| X->M1->Y | 0.16 | 1.00 (0.46) | 0.12 | 1.95 | 0.14 | 0.96 (0.45) | 0.09 | 1.87 |

| X->M2->Y | 0.03 | 0.16 (0.30) | −0.45 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 0.03 (0.35) | −0.64 | 0.73 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pyszkowska, A.; Stojek, M.M. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Self-Stigma in People with Physical Disabilities: The Role of Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710854

Pyszkowska A, Stojek MM. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Self-Stigma in People with Physical Disabilities: The Role of Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710854

Chicago/Turabian StylePyszkowska, Anna, and Monika M. Stojek. 2022. "Early Maladaptive Schemas and Self-Stigma in People with Physical Disabilities: The Role of Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710854

APA StylePyszkowska, A., & Stojek, M. M. (2022). Early Maladaptive Schemas and Self-Stigma in People with Physical Disabilities: The Role of Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710854