The Relationship of Technoference in Conjugal Interactions and Child Smartphone Dependence: The Chain Mediation between Marital Conflict and Coparenting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

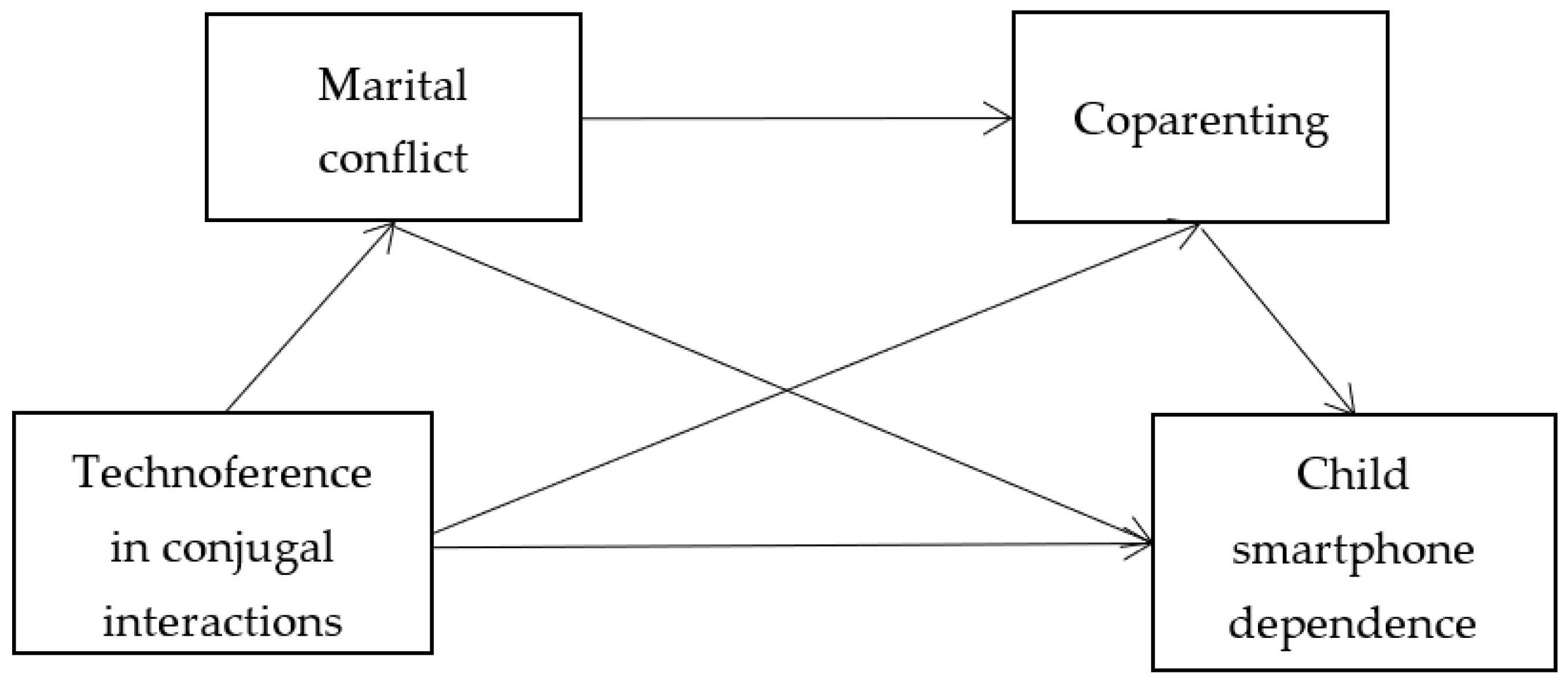

2. Research Model and Hypotheses

2.1. Technoference in Conjugal Interactions and Child Smartphone Dependence

2.2. The Mediating Role of Marital Conflict

2.3. The Mediating Role of Coparenting

2.4. A Chain Mediation Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Technoference in the Conjugal Interactions

3.2.2. Marital Conflict Scale

3.2.3. Coparenting Scale

3.2.4. Child Smartphone Dependence

3.2.5. Covariates

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Testing the Mediating Effects of Marital Conflict and Coparenting

5. Discussion

5.1. Technoference in Conjugal Interactions and Child Smartphone Dependence

5.2. The Mediating Role of Marital Conflict

5.3. The Mediating Role of Coparenting

5.4. The Chain Mediation Model

5.5. Limitations, Recommendations and Contribution

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDaniel, B.T.; Coyne, S.M. The interference of technology in the coparenting of young children: Implications for mothers’ perceptions of coparenting. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, L.A.; Coyne, S.M.; Padilla-Walker, L.M. Parent and Child Technoference and socioemotional behavioral outcomes: A nationally representative study of 10- to 20-year-Old adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 88, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Coyne, S.M. “Technoference”: The interference of technology in couple relationships and implications for women’s personal and relational well-being. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2016, 5, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiniker, A.; Sobel, K.; Suh, H.; Sung, Y.C.; Lee, C.P.; Kientz, J.A. Texting while parenting: How adults use mobile phones while caring for children at the playground. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 727–736. [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, A.; Heimann, M.; Koch, F.S. Relationship between family technoference and behavior problems in children aged 4–5 years. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewin, C.A.; Reupert, A.; McLean, L.A. Naturalistic Observations of Caregiver–Child Dyad Mobile Device Use. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 2042–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, S.; Beate, W.H.; Frode, S.; Silja, B.K.; Lars, W. Screen time and the development of emotion understanding from age 4 to age 8: A community study. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 37, 427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, S.; Wen, P.; Catherine, E.S. Are screen devices soothing children or soothing parents? Investigating the relationships among children’s exposure to different types of screen media, parental efficacy and home literacy practices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 112, 106462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K. A communication model of personal space violations: Explication and an initial test. Hum. Commun. Res. 1978, 4, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V.; Douglas, K.M. The effects of “phubbing” on social interaction. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, Y.-H.; Fang, Z.; Liu, M.-Y. The Roles of Parent-child Triangulation and Psychological Resilience in the Relationship between Interparental Conflict and Adolescents’ Problem Behaviors: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kochanska, G.; Kim, S. Early Attachment Organization With Both Parents and Future Behav Problems: From Infancy to Middle Childhood. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X. The Longitudinal Relationships between Family Functioning and Children’s Conduct Problems: The Moderating Role of Attentional Control Indexed by Intraindividual Response Time Variability. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2022, 44, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeytinoglu, S.; Calkins, S.D.; Leerkes, E.M. Maternal emotional support but not cognitive support during problem-solving predicts increases in cognitive flexibility in early childhood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2019, 43, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebel, S. Rethinking executive function and its development. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.E.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Early parenting and the intergenerational transmission of self-regulation and behavior problems in African American head start families. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 51, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Radesky, J.S. Technoference: Parent Distraction with Technology and Associations With Child Behavior Problems. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-X.; Wu, J.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Wang, W.-J. Parental technoference and smartphone addiction in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of social sensitivity and loneliness. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ye, B.; Luo, L.; Yu, L. The Effect of Parent Phubbing on Chinese Adolescents’ Smartphone Addiction During COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.-Y.; Lei, L.; Ou, M.-K.; Nie, J.-Y.; Wang, P.-C. The influence of perceived parental phubbing on adolescents’ problematic smartphone use: A two-wave multiple mediation model. Addict. Behav. 2021, 121, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppolat, G.; Righetti, F.; Balzarini, R.N.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; Urganci, B.; Rodrigues, D.L.; Debrot, A.; Wiwattanapantuwong, J.; Dharma, C.; Chi, P.; et al. Relationship difficulties and “technoference” during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaterlaus, J.M.; Stinson, R.; McEwen, M. Technology Use in Young Adult Marital Relationships: A Case Study Approach. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2020, 42, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Galovan, A.M.; Cravens, J.D.; Drouin, M. “Technoference” and implications for mothers’ and fathers’ couple and coparenting relationship quality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Drouin, M. Daily technology interruptions and emotional and relational well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Radesky, J.S. Technoference: Longitudinal associations between parent technology use, parenting stress, and child behavior problems. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 84, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisasca, E.; Miragoli, S.; Di-Blasio, P.; Feinberg, M. Co-parenting mediates the influence of marital satisfaction on child adjustment: The conditional indirect effect by parental empathy. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.-R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.-D. The Effect of Parental Marital Quality and Coparenting on Adolescent Problem Behavior:Simultaneously Spillover or Lagged Spillover? Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 740–748. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-X.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Z.-Q. Why parental phubbing is at risk for adolescent mobile phone addiction: A serial mediating model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.-Y.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Zhou, N.; Gao, S.-Q.; Li, B.-L. The Influence of Inter-parental Conflicts Intervention Programs on Family and Children. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2019, 6, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.-M.; Fang, X.-Y.; Ju, X.-Y.; Lan, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.-X. Effects of Conflict Resolution and Daily Communication on Predicting Marital Quality of Newlyweds. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 24, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, S.M.; Stockdale, L.; Busby, D.; Iverson, B.; Grant, D.M. “I luv u:)!”: A descriptive study of the media uses of individuals in romantic relationships. Fam. Relat. 2011, 60, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Galovan, A.M.; Drouin, M. Daily technoference, technology use during couple leisure time, and relationship quality. Media Psychol. 2020, 10, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; David, M.E. My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, C.J.; Carlson, R.G. The Dyadic Association among Technoference and Relationship and Sexual Satisfaction of Young Adult Couples. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2021, 47, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, K. Partner Phubbing and Marital Satisfaction: The Mediating Roles of Marital Interaction and Marital Conflict. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.-L.; Fang, X.-Y. The Relationship between Marital Conflict, Coping Style and Marital Satisfaction. Psychol. Explor. 2019, 29, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. Longitudinal influences of depressive moods on problematic mobile phone use and negative school outcomes among Korean adolescents. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2019, 40, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Luo, X.-Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.-X. Interparental Conflict Affects Adolescent Mobile Phone Addiction: Based on the Spillover Hypothesis and Emotional Security Theory. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 30, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.-J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Li, C.-J.; Wu, H.-M.; Zhou, C.-Y. Perceived Parental Conflict and Mobile Phone Dependence in High School Students:The Mediating Effect of Emotional Management. China J. Health Psychol. 2015, 23, 1695–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Ary, D.V.; Duncan, T.E.; Biglan, A.; Metzler, C.W.; Noell, J.W.; Smolkowski, K. Development of Adolescent Problem Behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1999, 27, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Guo, F.; Chen, Z.-Y. Relationship between Paternal Co-parenting and Children’s Behavioral Problems:A Multiple Mediation Model of Maternal Anxiety and Maternal Psychological Control. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M.E. The Internal Structure and Ecological Context of Coparenting: A Framework for Research and Intervention. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2003, 3, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Sakuma, K. Coparenting interventions for expecting parents. In Coparenting: A Conceptual and Clinical Examination of Fam. Systems; McHale, J., Lindahl, K.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Egeren, L.A. The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Ment. Heal. J. Off. Publ. World Assoc. Infant Ment. Health 2004, 25, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, X.-C.; Zhou, S.-Q. Effect of Marital Satisfaction and its Similarity on Coparenting in Family with Adolescence. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2016, 32, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Thomassin, K.; Suveg, C.; Davis, M.; Lavner, J.A.; Beach, S.R.H. Coparental affect, children’s emotion dysregulation, and parent and child depressive symptoms. Fam. Process. 2017, 56, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.K.; Parra, G.; Jiang, Q. The longitudinal and bidirectional relationships between cooperative coparenting and child behavioral problems in low-income, unmarried families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2019, 33, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.D.; Aparecida, C.M. Emotional and behavioral problems of children: Association between family functioning, coparenting and marital relationship. Acta Colomb. Psicol. 2019, 22, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E.W.; Futris, T.G. Foster caregivers’ marital and coparenting relationship experiences: A dyadic perspective. Fam. Relat. 2019, 68, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Teti, D.M.; Feinberg, M.E. Assessing coparenting relationships in daily life: The daily coparenting scale (D-Cop). J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 2396–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, X.-C. Dyadic Effects of Marital Satisfaction on Coparenting in Chinese Families: Based on Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the 17th National Conference of Psychology, Beijing, China, 11–12 October 2014; pp. 814–816. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann, K.M. Effects of marital conflict on subsequent triadic family interactions and parenting. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Y. Advanced Psychological Statistics, 3rd ed.; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.-M.; Yuan, C.-Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.-J.; Wang, Y. Materal Depression, Parental Conflict and Infant’s Problem Behavior: Moderated Mediating Effect. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 23, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Foerster, M.; Roser, K.; Schoeni, A.; Röösli, M. Problematic mobile phone use in adolescents: Derivation of a short scale MPPUS-10. Int. J. Public Health 2015, 60, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Hu, B.-Y.; Wu, H.; Winsler, A.; Chen, L. Family socioeconomic status and Chinese preschoolers’social skills: Examining underlying family processes. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Foster, C.A. Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ngoubene-Atioky, A. Does Number of Children Moderate the Link between Intimate Partner Violence and Marital Instability among Chinese Female Migrant Workers? Sex Roles 2019, 80, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L.R. Statistical Remedies for Common Method Biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, A.W.; Watson, A.M.; Kroustalis, C.M. Assessing common methods bias in organizational research. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New York, NY, USA, 26–28 April 2007; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Erceg-Hurn, D.M.; Mirosevich, V.M. Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Liu, J.-Q.; Liu, J. The effect of problematic Internet use on mathematics achievement: The mediating role of self-efficacy and the moderating role of teacher-student relationships. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Yao, L.; Wu, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, X. Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Thomas, M.F.; Stevic, A.; Schmuck, D. Fighting over Smartphones? Parents’ Excessive Smartphone Use, Lack of Control over Children’s Use, and Conflict. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 116, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.; Katz, J.E. Texting’s consequences for romantic relationships: A cross-lagged analysis highlights its risks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, T.-T.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.-L.; Sun, X.-H.; Li, S.-J. Parental marital conflict, negative emotions, phubbing, and academic burnout among college students in the postpandemic era: A multiple mediating models. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoon, Y.W. Effect of parental neglect on smartphone addiction in adolescents in South Korea. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 77, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P. Parental phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Self-esteem and perceived social support as moderators. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Shannon, J.D.; Mitchell, S.J.; West, J. Mexican American mothers and fathers’ prenatal attitudes and father prenatal involvement: Links to mother–infant interaction and father engagement. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Meng, X.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Kong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Mei, S. Association between parental marital conflict and Internet addiction: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 240, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erel, O.; Burman, B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wolfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Merkaš, M.; Perić, K.; Žulec, A. Parent distraction with technology and child social competence during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of parental emotional stability. J. Fam. Commun. 2021, 21, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljasir, S.; Zheng, Y. Present but Absent in the Digital Age: Testing a Conceptual Model of Phubbing and Relationship Satisfaction Among Married Couples. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 2022, 1402751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Technoference in conjugal interactions | 1.98 | 1.05 | - | |||

| 2 Marital conflict | 2.10 | 0.83 | 0.11 ** | - | ||

| 3 Coparenting | 5.51 | 0.95 | −0.14 ** | −0.50 ** | - | |

| 4 Child smartphone dependence | 2.28 | 1.28 | 0.71 ** | 0.10 ** | −0.14 ** | - |

| Path | Standardized β | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

| X → M1 → Y | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.027 |

| X → M2 → Y | 0.016 | 0.011 | 0.021 |

| X → M1 → M2 → Y | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.026 |

| Indirect effects | 0.051 | 0.039 | 0.063 |

| Total effect | 0.071 | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, T.; Zhu, C.; Quan, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. The Relationship of Technoference in Conjugal Interactions and Child Smartphone Dependence: The Chain Mediation between Marital Conflict and Coparenting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710949

Shao T, Zhu C, Quan X, Wang H, Zhang C. The Relationship of Technoference in Conjugal Interactions and Child Smartphone Dependence: The Chain Mediation between Marital Conflict and Coparenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710949

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Tingting, Chengwei Zhu, Xi Quan, Haitao Wang, and Cai Zhang. 2022. "The Relationship of Technoference in Conjugal Interactions and Child Smartphone Dependence: The Chain Mediation between Marital Conflict and Coparenting" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710949