Metformin and the Risk of Chronic Urticaria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Main Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

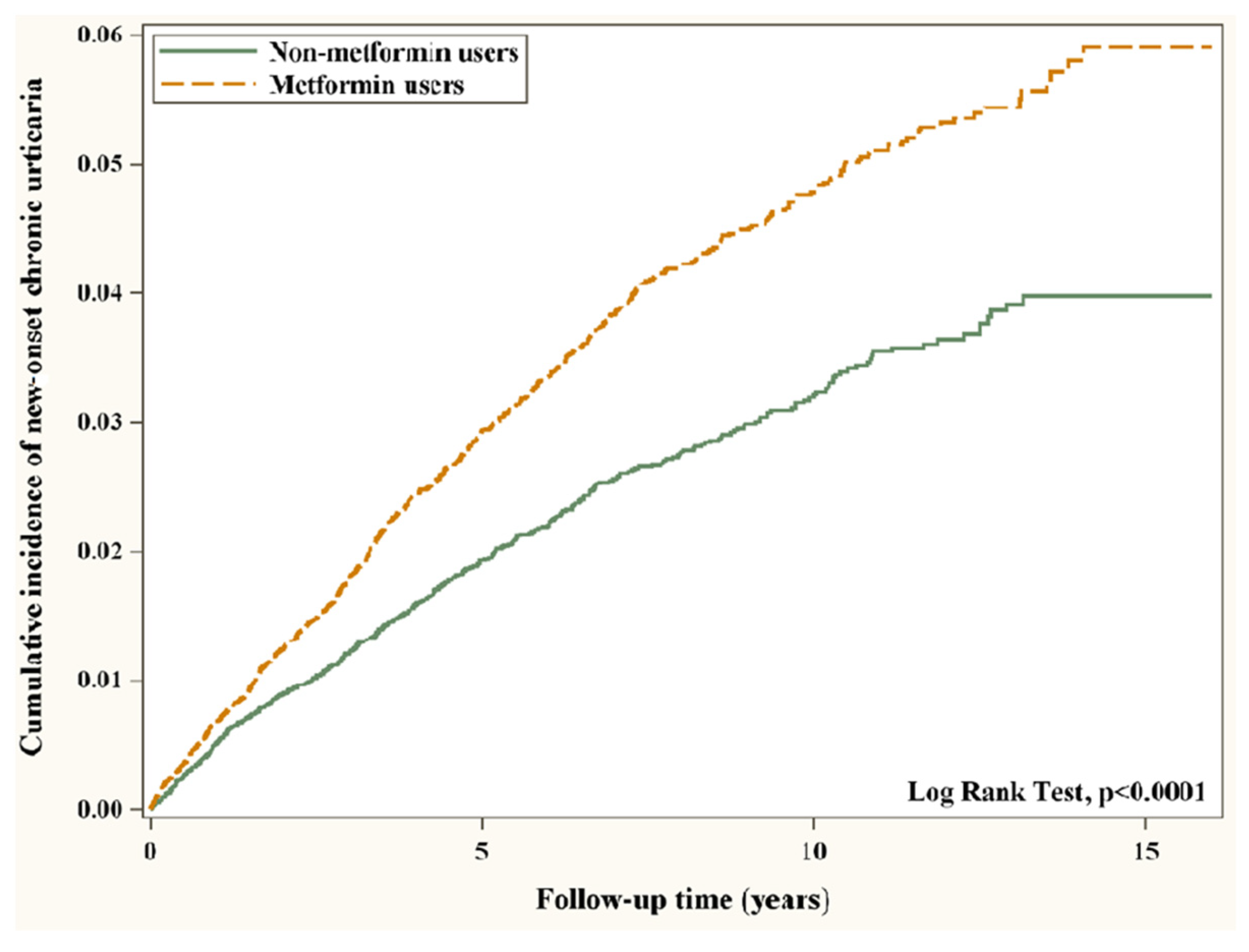

3.2. Main Outcomes

3.3. Cumulative Duration of Metformin Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanifin, J.M.; Reed, M.L. Eczema prevalence and impact working group. A population-based survey of eczema prevalence in the United States. Dermatitis 2007, 18, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, S.M.; Irvine, A.D.; Weidinger, S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020, 396, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antia, C.; Baquerizo, K.; Korman, A.; Bernstein, J.A.; Alikhan, A. Urticaria: A comprehensive review: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and work-up. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, M.W. Chronic urticaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom, G.; Magen, E.; Babaev, M.; Tiosano, S.; Vardy, D.A.; Linder, D.; Horev, A.; Saadia, A.; Comaneshter, D.; Agmon-Levin, N.; et al. Chronic urticaria and the metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional community-based study of 11 261 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMoia, T.E.; Shulman, G.I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin action. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Athari, S.S.; Mehrabi Nasab, E.; Zhao, L. PI3K/AKT/mTOR and TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB Signaling inhibitors attenuate pathological mechanisms of allergic Asthma. Inflammation 2021, 44, 1895–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Russo, E.; Pellino, G.; D’Angelo, S.; Chiaravalloti, A.; de Sarro, G.; Manfredini, R.; de Giorgio, R. Metformin and autoimmunity: A “new deal” of an old drug. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Huang, S.K. Metformin inhibits IgE- and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated mast cell activation in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018, 48, 1989–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, L.H.; Mcgovern, A.; Sherlock, J.; Gatenby, P.; Correa, A.; Creagh-Brown, B.; deLusignan, S. The impact of therapy on the risk of asthma in type 2 diabetes. Clin. Respir. J. 2019, 13, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Z.; Hsu, C.H.; Li, C.Y.; Hsiue, T.R. Insulin use increases risk of asthma but metformin use reduces the risk in patients with diabetes in a Taiwanese population cohort. J. Asthma 2017, 54, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, F.S.; Hsu, C.C.; Shih, Y.H.; Pan, W.L.; Wei, J.C.C.; Hwu, C.M. Metformin and the development of Asthma in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C.; Lai, M.S.; Syu, C.Y.; Chang, S.C.; Tseng, F.Y. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2005, 104, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meduru, P.; Helmer, D.; Rajan, M.; Tseng, C.L.; Pogach, L.; Sambamoorthi, U. Chronic illness with complexity: Implications for performance measurement of optimal glycemic control. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.A.; Lin, E.; von Korff, M.; Simon, G.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.J.; Everson-Stewart, S.; Kinder, L.; Oliver, M.; Boyko, E.J.; et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and health care utilization. Am. J. Manag. Care 2008, 14, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.Y.; Cho, Y.T.; Jiang, J.H.; Chang, C.C.; Liao, S.C.; Tang, C.H. Patients with chronic urticaria have a higher risk of psychiatric disorders: A population-based study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, R.B., Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 2265–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Erickson, S.R.; Wu, C.H. Metformin use and asthma outcomes among patients with concurrent asthma and diabetes. Respirology 2016, 21, 1210–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.D.; Keet, C.A.; Fawzy, A.; Segal, J.B.; Brigham, E.P.; McCormack, M.C. Association of metformin initiation and risk of asthma exacerbation. A claims-based cohort study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naffaa, M.E.; Rosenberg, V.; Watad, A.; Tiosano, S.; Yavne, Y.; Chodick, G.; Amital, H.; Shalev, V. Adherence to metformin and the onset of rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based cohort study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 49, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchli, Y.B.; Jick, S.S.; Curtin, F.; Meier, C.R. Association between use of thiazolidinediones or other oral antidiabetics and psoriasis: A population based case-control study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 58, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Y.; Shieh, J.J.; Shen, J.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Chang, Y.T.; Chen, Y.J. Association between antidiabetic drugs and psoriasis risk in diabetic patients: Results from a nationwide nested case-control study in Taiwan. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubna, A.K. Metformin—For the dermatologist. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2016, 48, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koca, R.; Altinyazar, H.C.; Yenidünya, S.; Tekin, N.S. Psoriasiform drug eruption associated with metformin hydrochloride: A case report. Dermatol. Online J. 2003, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Vazquez, T.; Lechner, S.; Blomberg, B.B.; Frasca, D. Metformin improves in vivo and in vitro B cell function in individuals with obesity and type-2 diabetes. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2694–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saenwongsa, W.; Nithichanon, A.; Chittaganpitch, M.; Buayai, K.; Kewcharoenwong, C.; Thumrongwilainet, B.; Butta, P.; Palaga, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Ato, M.; et al. Metformin-induced suppression of IFN-α via mTORC1 signalling following seasonal vaccination is associated with impaired antibody responses in type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, S.A.; Williams, E.S.; Zhu, M. No effect of metformin on the innate airway hyperresponsiveness and increased responses to ozone observed in obese mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 105, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Pre-Matched | Post-Matched | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Metformin Users | Metformin Users | SMD § | Non-Metformin Users | Metformin Users | SMD § | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| All | 40,476 | 116,262 | 0.2784 | 24,987 | 24,987 | 0.0020 |

| Sex | 0.1221 | 0.0199 | ||||

| Female | 20,381 (50.35) | 51,467 (44.27) | 11,981 (47.95) | 12,230 (48.95) | ||

| Male | 20,095 (49.65) | 64,795 (55.73) | 13,006 (52.05) | 12,757 (51.05) | ||

| Age group (year) | ||||||

| 20–39 | 3029 (7.48) | 9948 (8.56) | 0.0395 | 1949 (7.80) | 1736 (6.95) | 0.0326 |

| 40–59 | 15,986 (39.50) | 59,541 (51.21) | 0.2370 | 10,462 (41.87) | 10,185 (40.76) | 0.0225 |

| 60+ | 21,461 (53.02) | 46,773 (40.23) | 0.2585 | 12,576 (50.33) | 13,066 (52.29) | 0.0392 |

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 59.51 ± 12.50 | 56.27 ± 11.86 | 0.2665 | 58.85 ± 12.50 | 59.41 ± 12.30 | 0.0453 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Obesity | 0.0008 | 0.0098 | ||||

| No | 39,936 (98.67) | 114,700 (98.66) | 24,649 (98.65) | 24,620 (98.53) | ||

| Yes | 540 (1.33) | 1562 (1.34) | 338 (1.35) | 367 (1.47) | ||

| Smoking status | 0.0297 | 0.0015 | ||||

| No | 39,724 (98.14) | 114,544 (98.52) | 24,561 (98.30) | 24,556 (98.28) | ||

| Yes | 752 (1.86) | 1718 (1.48) | 426 (1.70) | 431 (1.72) | ||

| Alcohol-related disorders | 0.0440 | 0.0029 | ||||

| No | 39,188 (96.82) | 113,409 (97.55) | 24,189 (96.81) | 24,176 (96.75) | ||

| Yes | 1288 (3.18) | 2853 (2.45) | 798 (3.19) | 811 (3.25) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.0713 | 0.0542 | ||||

| No | 16,440 (40.62) | 51,314 (44.14) | 9934 (39.76) | 9276 (37.12) | ||

| Yes | 24,036 (59.38) | 64,948 (55.86) | 15,053 (60.24) | 15,711 (62.88) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.2041 | 0.0546 | ||||

| No | 17,065 (42.16) | 60,802 (52.30) | 11,237 (44.97) | 10,561 (42.27) | ||

| Yes | 23,411 (57.84) | 55,460 (47.70) | 13,750 (55.03) | 14,426 (57.73) | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 0.2014 | 0.0378 | ||||

| No | 28,037 (69.27) | 90,790 (78.09) | 17,813 (71.29) | 17,382 (69.56) | ||

| Yes | 12,439 (30.73) | 25,472 (21.91) | 7174 (28.71) | 7605 (30.44) | ||

| Stroke | 0.2054 | 0.0332 | ||||

| No | 33,211 (82.05) | 103,727 (89.22) | 20,946 (83.83) | 20,636 (82.59) | ||

| Yes | 7265 (17.95) | 12,535 (10.78) | 4041 (16.17) | 4351 (17.41) | ||

| Heart failure | 0.1284 | 0.0111 | ||||

| No | 37,635 (92.98) | 111,513 (95.92) | 23,350 (93.45) | 23,281 (93.17) | ||

| Yes | 2841 (7.02) | 4749 (4.08) | 1637 (6.55) | 1706 (6.83) | ||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 0.0841 | 0.0041 | ||||

| No | 39,085 (96.56) | 113,864 (97.94) | 24,217 (96.92) | 24,199 (96.85) | ||

| Yes | 1391 (3.44) | 2398 (2.06) | 770 (3.08) | 788 (3.15) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.2572 | 0.0019 | ||||

| No | 36,554 (90.31) | 112,328 (96.62) | 23,196 (92.83) | 23,208 (92.88) | ||

| Yes | 3922 (9.69) | 3934 (3.38) | 1791 (7.17) | 1779 (7.12) | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.1964 | 0.0156 | ||||

| No | 32,434 (80.13) | 101,549 (87.34) | 20,492 (82.01) | 20,341 (81.41) | ||

| Yes | 8042 (19.87) | 14,713 (12.66) | 4495 (17.99) | 4646 (18.59) | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.0787 | 0.0009 | ||||

| No | 39,455 (97.48) | 114,602 (98.57) | 24,480 (97.97) | 24,477 (97.96) | ||

| Yes | 1021 (2.52) | 1660 (1.43) | 507 (2.03) | 510 (2.04) | ||

| Systemic lupus erythematous | 0.0547 | 0.0077 | ||||

| No | 40,310 (99.59) | 116,114 (99.87) | 24,914 (99.71) | 24,924 (99.75) | ||

| Yes | 166 (0.41) | 148 (0.13) | 73 (0.29) | 63 (0.25) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.0934 | 0.0130 | ||||

| No | 39,274 (97.03) | 114,427 (98.42) | 24,360 (97.49) | 24,308 (97.28) | ||

| Yes | 1202 (2.97) | 1835 (1.58) | 627 (2.51) | 679 (2.72) | ||

| Cancers | 0.1492 | 0.0137 | ||||

| No | 37,796 (93.38) | 112,335 (96.62) | 23,659 (94.69) | 23,581 (94.37) | ||

| Yes | 2680 (6.62) | 3927 (3.38) | 1328 (5.31) | 1406 (5.63) | ||

| Psychosis | 0.0434 | 0.0059 | ||||

| No | 39,507 (97.61) | 114,199 (98.23) | 24,438 (97.80) | 24,416 (97.71) | ||

| Yes | 969 (2.39) | 2063 (1.77) | 549 (2.20) | 571 (2.29) | ||

| Depression | 0.1390 | 0.0070 | ||||

| No | 37,855 (93.52) | 112,237 (96.54) | 23,685 (94.79) | 23,646 (94.63) | ||

| Yes | 2621 (6.48) | 4025 (3.46) | 1302 (5.21) | 1341 (5.37) | ||

| Dementia | 0.0886 | 0.0073 | ||||

| No | 40,185 (99.28) | 116,099 (99.86) | 24,871 (99.54) | 24,883 (99.58) | ||

| Yes | 291 (0.72) | 163 (0.14) | 116 (0.46) | 104 (0.42) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||||

| 0 | 26,627 (65.78) | 92,391 (79.47) | 0.3106 | 17,269 (69.11) | 16,821 (67.32) | 0.0385 |

| 1 | 5201 (12.85) | 12,028 (10.35) | 0.0783 | 3193 (12.78) | 3412 (13.66) | 0.0259 |

| 2+ | 8648 (21.37) | 11,843 (10.19) | 0.3104 | 4525 (18.11) | 4754 (19.03) | 0.0236 |

| Diabetes Complications Severity Index | ||||||

| 0 | 12,926 (31.93) | 54,792 (47.13) | 0.3146 | 8964 (35.87) | 8036 (32.16) | 0.0785 |

| 1 | 7530 (18.60) | 21,500 (18.49) | 0.0029 | 4692 (18.78) | 4936 (19.75) | 0.0248 |

| 2+ | 20,020 (49.46) | 39,970 (34.38) | 0.3093 | 11,331 (45.35) | 12,015 (48.09) | 0.0549 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Numbers of oral antidiabetic drugs | ||||||

| <2 | 39,780 (98.28) | 111,718 (96.09) | 0.1327 | 24,393 (97.62) | 24,264 (97.11) | 0.0322 |

| 2–3 | 690 (1.70) | 4508 (3.88) | 0.1322 | 589 (2.36) | 716 (2.87) | 0.0319 |

| >3 | 6 (0.01) | 36 (0.03) | 0.0107 | 5 (0.02) | 7 (0.03) | 0.0052 |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists | 0.0059 | 0.0052 | ||||

| No | 40,476 (100.00) | 116,262 (100.00) | 24,987 (100.00) | 24,987 (100.00) | ||

| Yes | ||||||

| Insulins | 0.2107 | 0.0297 | ||||

| No | 31,443 (77.68) | 99,730 (85.78) | 19,659 (78.68) | 19,352 (77.45) | ||

| Yes | 9033 (22.32) | 16,532 (14.22) | 5328 (21.32) | 5635 (22.55) | ||

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 0.8256 | 0.0937 | ||||

| No | 6349 (15.69) | 60,183 (51.76) | 6081 (24.34) | 5106 (20.43) | ||

| Yes | 34,127 (84.31) | 56,079 (48.24) | 18,906 (75.66) | 19,881 (79.57) | ||

| Statins | 0.2569 | 0.0430 | ||||

| No | 28,760 (71.05) | 95,178 (81.87) | 18,623 (74.53) | 18,149 (72.63) | ||

| Yes | 11,716 (28.95) | 21,084 (18.13) | 6364 (25.47) | 6838 (27.37) | ||

| Aspirin | 0.2706 | 0.0342 | ||||

| No | 28,799 (71.15) | 95,881 (82.47) | 18,291 (73.20) | 17,909 (71.67) | ||

| Yes | 11,677 (28.85) | 20,381 (17.53) | 6696 (26.80) | 7078 (28.33) | ||

| Duration of T2D (year) | 4.09 ± 3.68 | 2.08 ± 3.13 | 0.5901 | 3.44 ± 3.29 | 3.54 ± 3.70 | 0.0293 |

| HbA1c check-up > 2 per year | 1.3409 | 0.0466 | ||||

| No | 35,846 (88.56) | 39,944 (34.36) | 20,383 (81.57) | 19,923 (79.73) | ||

| Yes | 4630 (11.44) | 76,318 (65.64) | 4604 (18.43) | 5064 (20.27) | ||

| Variable | Non-Metformin Users | Metformin Users | Crude HR | Adjusted HR # | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Person-Years | IR * | Event | Person-Years | IR * | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| New-onset chronic urticaria | 496 | 142,255 | 3.49 | 819 | 158,517 | 5.17 | 1.49 (1.33, 1.66) | <0.0001 | 1.56 (1.39, 1.74) | <0.0001 |

| Severe chronic urticaria | 9 | 145,454 | 0.06 | 4 | 164,410 | 0.02 | 0.39 (0.12, 1.27) | 0.1177 | 0.40 (0.12, 1.30) | 0.1264 |

| Hospitalization for chronic urticaria | 19 | 145,399 | 0.13 | 33 | 164,297 | 0.2 | 1.53 (0.87, 2.70) | 0.1369 | 1.45 (0.82, 2.56) | 0.2009 |

| Variable | Event | Person-Years | IR * | Crude HR | Adjusted HR # | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||||

| New-onset chronic urticaria | |||||||

| Non-metformin users | 496 | 142,255 | 3.49 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Metformin users | |||||||

| 1–31 days/years | 177 | 42,992 | 4.12 | 1.19 (1.00, 1.41) | 0.0515 | 1.15 (0.97, 1.37) | 0.1051 |

| 32–88 days/years | 164 | 39,889 | 4.11 | 1.18 (0.99, 1.41) | 0.0599 | 1.21 (1.01, 1.44) | 0.0346 |

| 89–145 days/years | 142 | 39,230 | 3.62 | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25) | 0.6950 | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) | 0.1021 |

| >145 days/years | 336 | 36,405 | 9.23 | 2.67 (2.32, 3.07) | <0.0001 | 3.02 (2.62, 3.48) | <0.0001 |

| Severe chronic urticaria | |||||||

| Non-metformin users | 9 | 145,454 | 0.06 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Metformin users | |||||||

| 1–31 days/years | 4 | 164,410 | 0.07 | 1.10 (0.30, 4.07) | 0.8867 | 1.15 (0.30, 4.43) | 0.8344 |

| 32–88 days/years | 0.00 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 89–145 days/years | 0.00 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| >145 days/years | 0.03 | 0.42 (0.05, 3.31) | 0.4097 | 0.42 (0.05, 3.36) | 0.4131 | ||

| Hospitalization for chronic urticaria | |||||||

| Non-metformin users | 19 | 145,399 | 0.13 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| Metformin users | |||||||

| 1–31 days/years | 9 | 43,815 | 0.21 | 1.57 (0.71, 3.47) | 0.2649 | 1.38 (0.62, 3.08) | 0.4274 |

| 32–88 days/years | 7 | 41,090 | 0.17 | 1.30 (0.55, 3.09) | 0.5539 | 1.25 (0.53, 2.98) | 0.6124 |

| 89–145 days/years | 5 | 40,744 | 0.12 | 0.94 (0.35, 2.52) | 0.9009 | 0.94 (0.35, 2.53) | 0.8958 |

| >145 days/years | 12 | 38,648 | 0.31 | 2.37 (1.15, 4.89) | 0.0191 | 2.27 (1.09, 4.74) | 0.0284 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yen, F.-S.; Hsu, C.-C.; Hu, K.-C.; Hung, Y.-T.; Hsu, C.Y.; Wei, J.C.-C.; Hwu, C.-M. Metformin and the Risk of Chronic Urticaria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711045

Yen F-S, Hsu C-C, Hu K-C, Hung Y-T, Hsu CY, Wei JC-C, Hwu C-M. Metformin and the Risk of Chronic Urticaria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):11045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711045

Chicago/Turabian StyleYen, Fu-Shun, Chih-Cheng Hsu, Kai-Chieh Hu, Yu-Tung Hung, Chung Y. Hsu, James Cheng-Chung Wei, and Chii-Min Hwu. 2022. "Metformin and the Risk of Chronic Urticaria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 11045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711045