How Work-Family Conflict Influenced the Safety Performance of Subway Employees during the Initial COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Chained Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Work-Family Conflict

2.3.2. Job Burnout

2.3.3. Affective Commitment

2.3.4. Safety Performance

2.3.5. Control Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables

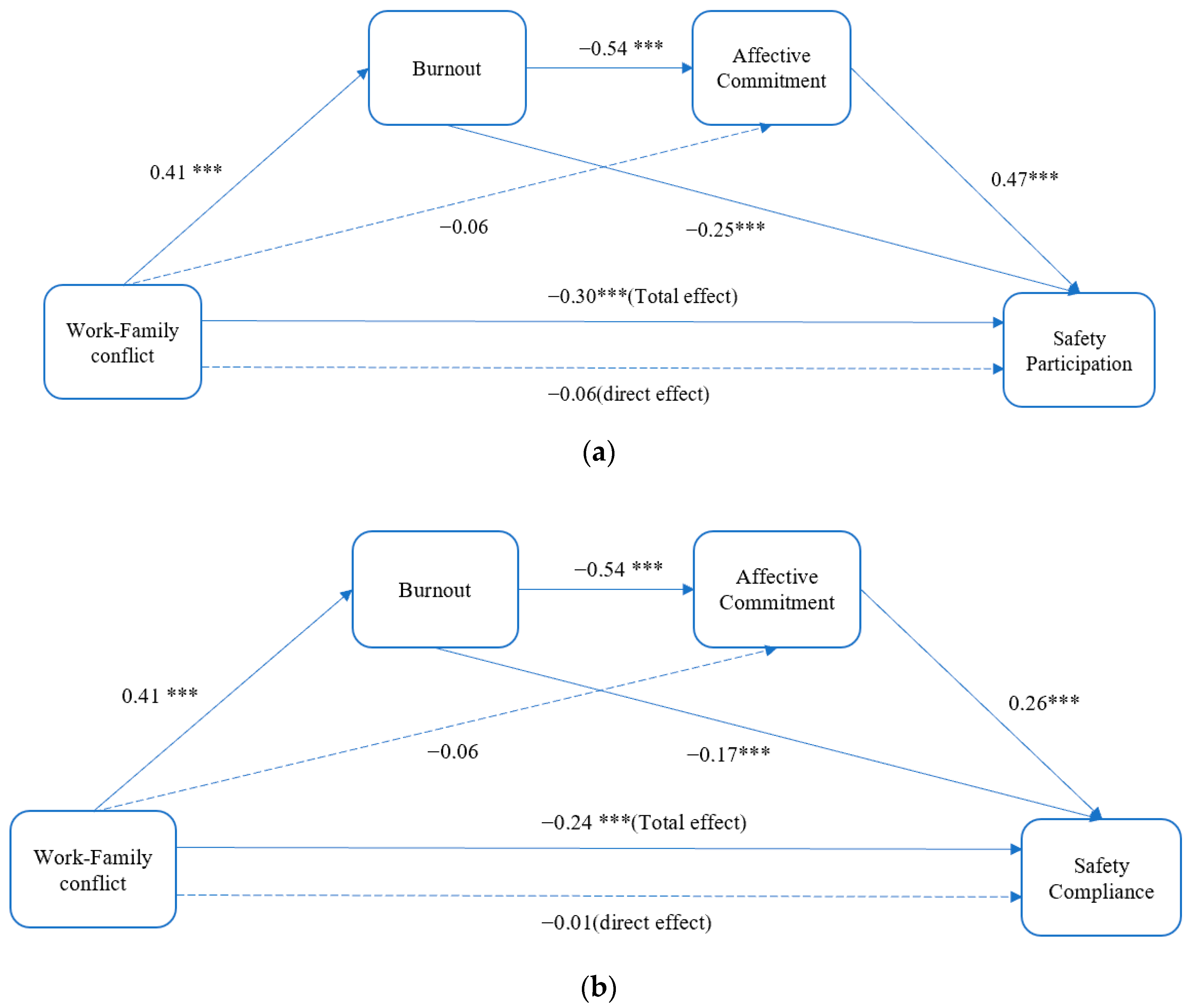

3.3. Chain Mediation Effect Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Velavan, T.P.; Meyer, C.G. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2020, 25, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19—11 May 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---11-may-2022 (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. Pandemic Grief Scale: A screening tool for dysfunctional grief due to a COVID-19 loss. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Dosil Santamaria, M.; Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. Psychological Symptoms During the Two Stages of Lockdown in Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Investigation in a Sample of Citizens in Northern Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, L.S.; Tan, J.Y.C.; Chew, T.W.Y. The Influence of COVID-19 on Women’s Perceptions of work-family conflict in Singapore. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, S.J.; Ji, T.T.; Song, Y.L. Relationship between risk perception of COVID-19 and job withdrawal among Chinese nurses: The effect of work-family conflict and job autonomy. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yldrm, M.; Solmaz, F. COVID-19 Burnout, COVID-19 Stress and Resilience: Initial Psychometric Properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Stud. 2020, 46, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moron, M.; Yildirim, M.; Jach, L.; Nowakowska, J.; Atlas, K. Exhausted due to the pandemic: Validation of Coronavirus Stress Measure and COVID-19 Burnout Scale in a Polish sample. Curr. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutell, G.N.J. Sources of Conflict Between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, M.; Peters, E.; Diewald, M. COVID-19 and work-family conflicts in Germany: Risks and Chances Across Gender and Parenthood. Front. Sociol. 2022, 6, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, A.; Su, X.; Zhang, S.; Guan, W.; Li, J. Psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on frontline nurses: A cross-sectional survey study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4217–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nippert-Eng, C.E. Home and Work: Negotiating Boundaries through Everyday Life. Contemp. Sociol. 1998, 75, 153–154. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N. Sources of work-family conflict: A Sino-U.S. Comparison of the Effects of Work and Family Demands. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y.; Low, S.P. Work–family conflicts experienced by project managers in the Chinese construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.C.; Hammer, L.B. Developing and testing a theoretical model linking work-family conflict to employee safety. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.L.; Guo, M.; Liu, S.Z.; Chen, S.L. work-family conflict, personality, and safety behaviors among high-speed railway drivers. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2020, 12, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Johnson, R.C.; Crain, T.L.; Bodner, T.; Kossek, E.E.; Davis, K.D.; Kelly, E.L.; Buxton, O.M.; Karuntzos, G.; Chosewood, L.C.; et al. Intervention Effects on Safety Compliance and Citizenship Behaviors: Evidence From the Work, Family, and Health Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, J.; Zhang, P.; Wu, G.P.H. Investigating the Relationship between Work-To-Family Conflict, Job Burnout, Job Outcomes, and Affective Commitment in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Weaver, J.S.; Revels, J.W. Provocative thoughts from COVID-19: Physician-centric solutions to physician burnout. Clin. Imaging 2021, 78, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T.; Yirci, R.; Papadakis, S. Examining the Associations between COVID-19-Related Psychological Distress, Social Media Addiction, COVID-19-Related Burnout, and Depression among School Principals and Teachers through Structural Equation Modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.D.; Herst, D.E.; Bruck, C.S.; Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A Meta-Analysis of work-family conflict and Various Outcomes With a Special Emphasis on Cross-Domain Versus Matching-Domain Relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Haines, V.Y.; Harvey, S.; Durand, P.; Marchand, A. Core Self-Evaluations, WorkFamily Conflict, and Burnout. J. Marriage Fam. 2013, 75, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Greenglass, E.R. Hospital restructuring, work-family conflict and psychological burnout among nursing staff. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; DeJoy, D.M.; Dyal, M.A.; Huang, G.J. Impact of work pressure, work stress and work-family conflict on firefighter burnout. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2019, 74, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Yang, S.; Song, S. A Survey on Work Stress and Job Burnout of Locomotive Driver on Safety Performance. China Saf. Sci. J. CSSJ 2013, 23, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.D.; Hughes, K.; DeJoy, D.M.; Dyal, M.A. Assessment of relationships between work stress, work-family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Saf. Sci. 2018, 103, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.W.; Gou, X.Q.; Li, H.Y.; Xia, N.N.; Wu, G.D. Linking work-family conflict and burnout from the emotional resource perspective for construction professionals. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 1093–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, J.Z. Psychosocial safety climate and unsafe behavior among miners in China: The mediating role of work stress and job burnout. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 25, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Dong, Y.; Li, J.Z. Influence of job insecurity on coal miners’ safety performance: The role of emotional exhaustion. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.X.; Liu, H. Analysis of the Influence of Psychological Contract on Employee Safety Behaviors against COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Tremblay, D.G. How can we decrease burnout and safety workaround behaviors in health care organizations? The role of psychosocial safety climate. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 528–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.Y.; Dan, C.L. Job Burnout, work-family conflict and Project Performance for Construction Professionals: The Moderating Role of Organizational Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mccormick, L.; Donohue, R. Antecedents of affective and normative commitment of organisational volunteers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 2581–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Duarte, A.P.; Filipe, R.; Oliveira, R.T.D. How Authentic Leadership Promotes Individual Creativity: The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, K.M. Motivation for entry, occupational commitment and intent to remain: A survey regarding Registered Nurse retention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2532–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.Y.; Shyu, Y.I.L.; Wong, M.K.; Chu, T.L.; Lo, Y.Y.; Teng, C.I. How does burnout impact the three components of nursing professional commitment? Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, I.; Zito, M.; Colombo, L.; Cortese, C.G.; Ghislieri, C.; Argentero, P. Well-Being and Affective Commitment among Ambulance Volunteers: A Mediational Model of Job Burnout. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2018, 44, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D. Examination of Safety Climate, Affective Organizational Commitment, and Safety Behavior Outcomes Among Fire Service Personnel. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 14, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at Work: A Meta-Analytic Investigation of the Link Between Job Demands, Job Resources, Burnout, Engagement, and Safety Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcuruto, M.; Griffin, M.A. Prosocial and proactive “safety citizenship behaviour” (SCB): The mediating role of affective commitment and psychological ownership. Saf. Sci. 2018, 104, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Dhar, R.L. Factors influencing job performance of nursing staff Mediating role of affective commitment. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, B.; van de Voorde, K.; van Veldhoven, M. Cross-level effects of high-performance work practices on burnout Two counteracting mediating mechanisms compared. Pers. Rev. 2009, 38, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Suar, D.; Leiter, M.P. Antecedents, Work-Related Consequences, and Buffers of Job Burnout Among Indian Software Developers. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2012, 19, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Thaichon, P. Revisiting the job performance—Burnout relationship. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 807–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enginyurt, O.; Cankaya, S.; Aksay, K.; Tunc, T.; Koc, B.; Bas, O.; Ozer, E. Relationship between organisational commitment and burnout syndrome: A canonical correlation approach. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; Mcmurrian, R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, R.I.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Hamdan, S. Examining the Relationships Between Frontline Bank Employees’ Job Demands and Job Satisfaction: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sage Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, K.; Luo, Z. work-family conflict and Job Burnout of Doctors and Nurses. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2003, 12, 807–809. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Qu, Z. Vocational and Technical College Teachers’ Psychological Contract and Job Burnout: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 19, 234–236. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, F.R.; Rosenberg, M.; McCord, J. Self-esteem and delinquency. J. Youth Adolesc. 1978, 7, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolin, J.H. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. J. Educ. Meas. 2014, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, S.; Kuntsche, E. Drinking to cope mediates the link between work-family conflict and alcohol use among mothers but not fathers of preschool children. Addict. Behav. 2021, 112, 106665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Mullins-Jaime, C.; Dyal, M.A.; DeJoy, D.M. Stress, burnout and diminished safety behaviors: An argument for Total Worker Health (R) approaches in the fire service. J. Saf. Res. 2020, 75, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Guo, M.; Ye, L.; Liao, G.L.; Yang, Z.H. work-family conflict and safety participation of high-speed railway drivers: Job satisfaction as a mediator. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 95, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.H.; Xia, N.N.; Yang, G.S. Do Family Affairs Matter? work-family conflict and Safety Behavior of Construction Workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04021074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F.; Laguia, A.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Security Providing Leadership: A Job Resource to Prevent Employees’ Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, S.K.; Horwitz, I.B. The effects of organizational commitment and structural empowerment on patient safety culture An analysis of a physician cohort. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2017, 31, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akar, H. The Relationships between Quality of Work Life, School Alienation, Burnout, Affective Commitment and Organizational Citizenship: A Study on Teachers. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 7, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | Variable | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 71 |

| Male | 29 | |

| Age | 19–25 | 73.89 |

| 26–30 | 21.99 | |

| 31–46 | 4.12 | |

| Work experience | 0–3 years | 74.52 |

| 4–6 years | 15.35 | |

| >6 years | 10.13 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 78.84 |

| Married | 21.16 | |

| Level of education | College | 75.52 |

| Undergraduate | 24.07 | |

| Graduate and above | 0.41 | |

| Sleep hours | <6 h | 27.53 |

| 6–8 h | 68.82 | |

| 9–10 h | 3.16 | |

| >10 h | 0.49 |

| Constructs | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.29 | 0.45 | -- | |||||||

| 2. Work experience | 2.54 | 2.59 | 0.03 | -- | ||||||

| 3. Self-esteem | 30.61 | 4.58 | 0.12 ** | 0.03 | -- | |||||

| 4. work-family conflict | 31.91 | 12.28 | 0.10 * | 0.07 | −0.35 ** | 0.76 | ||||

| 5. Job burnout | 30.68 | 14.22 | −0.11 ** | 0.09* | −0.58 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.69 | |||

| 6. Affective commitment | 17.37 | 3.16 | 0.01 | −0.13** | 0.34 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.58 ** | 0.89 | ||

| 7. Safety participation | 17.89 | 2.84 | 0.11 ** | −0.03 | 0.43 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.57 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.86 | |

| 8. Safety compliance | 19.46 | 1.89 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.33 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.40 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.91 |

| Variables | Range | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work-family conflict | 8–57 | Very Low < 15 | 123 | 19.46 |

| Low 15–25 | 210 | 33.23 | ||

| Medium 26–35 | 218 | 34.49 | ||

| High 36–45 | 64 | 10.13 | ||

| Very high > 45 | 17 | 2.69 | ||

| Job burnout | 15–105 | Very low < 30 | 103 | 16.30 |

| Low 31–50 | 268 | 42.40 | ||

| Medium 51–70 | 236 | 37.34 | ||

| High 71–90 | 24 | 3.80 | ||

| Very high > 90 | 1 | 0.16 | ||

| Affective commitment | 3–21 | Very Low < 10 | 6 | 0.95 |

| Low 10–15 | 170 | 26.90 | ||

| Medium 16–20 | 299 | 47.31 | ||

| High > 20 | 157 | 24.84 | ||

| Safety participation | 3–21 | Very low < 14 | 61 | 9.65 |

| Low 14–17 | 161 | 25.47 | ||

| Medium 18–20 | 217 | 34.34 | ||

| High > 20 | 193 | 30.54 | ||

| Safety compliance | 3–21 | Very low < 14 | 1 | 0.16 |

| Low 14–17 | 72 | 11.39 | ||

| Medium 18–20 | 246 | 38.92 | ||

| High > 20 | 313 | 49.53 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Burnout | Affective Commitment | Safety Participation | Safety Compliance | ||||||

| M1 | M2-1 | M2-2 | M3-1 | M3-2 | M3-3 | M4-1 | M4-2 | M4-3 | |

| 1. Self-esteem | −0.44 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.01 | 0.37 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.14 *** |

| 2. Work-family conflict | 0.41 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.06 | −0.17 *** | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.15 *** | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| 3. Job burnout | −0.54 *** | −0.50 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.17 *** | ||||

| 4. Affective commitment | 0.47 *** | 0.26 *** | |||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.48 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.22 *** |

| ∆R2 | 0.48 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.05 *** |

| Indirect Effects | Effect | Boot SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||

| Dependent variable: Safety participation | ||||

| Work-family conflict --> Job burnout --> Safety participation | −0.10 *** | 0.02 | −0.14 | −0.06 |

| Work-family conflict --> Affective commitment --> Safety participation | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| Work-family conflict --> Job burnout --> Affective commitment --> Safety participation | −0.10 *** | 0.02 | −0.14 | −0.08 |

| Dependent variable: Safety compliance | ||||

| Work-family conflict --> Job burnout --> Safety compliance | −0.07 *** | 0.02 | −0.11 | −0.03 |

| Work-family conflict --> Affective commitment --> Safety compliance | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Work-family conflict --> Job burnout --> Affective commitment --> Safety compliance | −0.06 *** | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.04 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Fu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, R.; Guo, Q. How Work-Family Conflict Influenced the Safety Performance of Subway Employees during the Initial COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Chained Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711056

Zhang J, Fu Y, Guo Z, Li R, Guo Q. How Work-Family Conflict Influenced the Safety Performance of Subway Employees during the Initial COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Chained Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):11056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711056

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jingyu, Yao Fu, Zizheng Guo, Ranran Li, and Qiaofeng Guo. 2022. "How Work-Family Conflict Influenced the Safety Performance of Subway Employees during the Initial COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Chained Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 11056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711056

APA StyleZhang, J., Fu, Y., Guo, Z., Li, R., & Guo, Q. (2022). How Work-Family Conflict Influenced the Safety Performance of Subway Employees during the Initial COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Chained Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711056