Methods for Successful Aging: An Aesthetics-Oriented Perspective Derived from Richard Shusterman’s Somaesthetics

Abstract

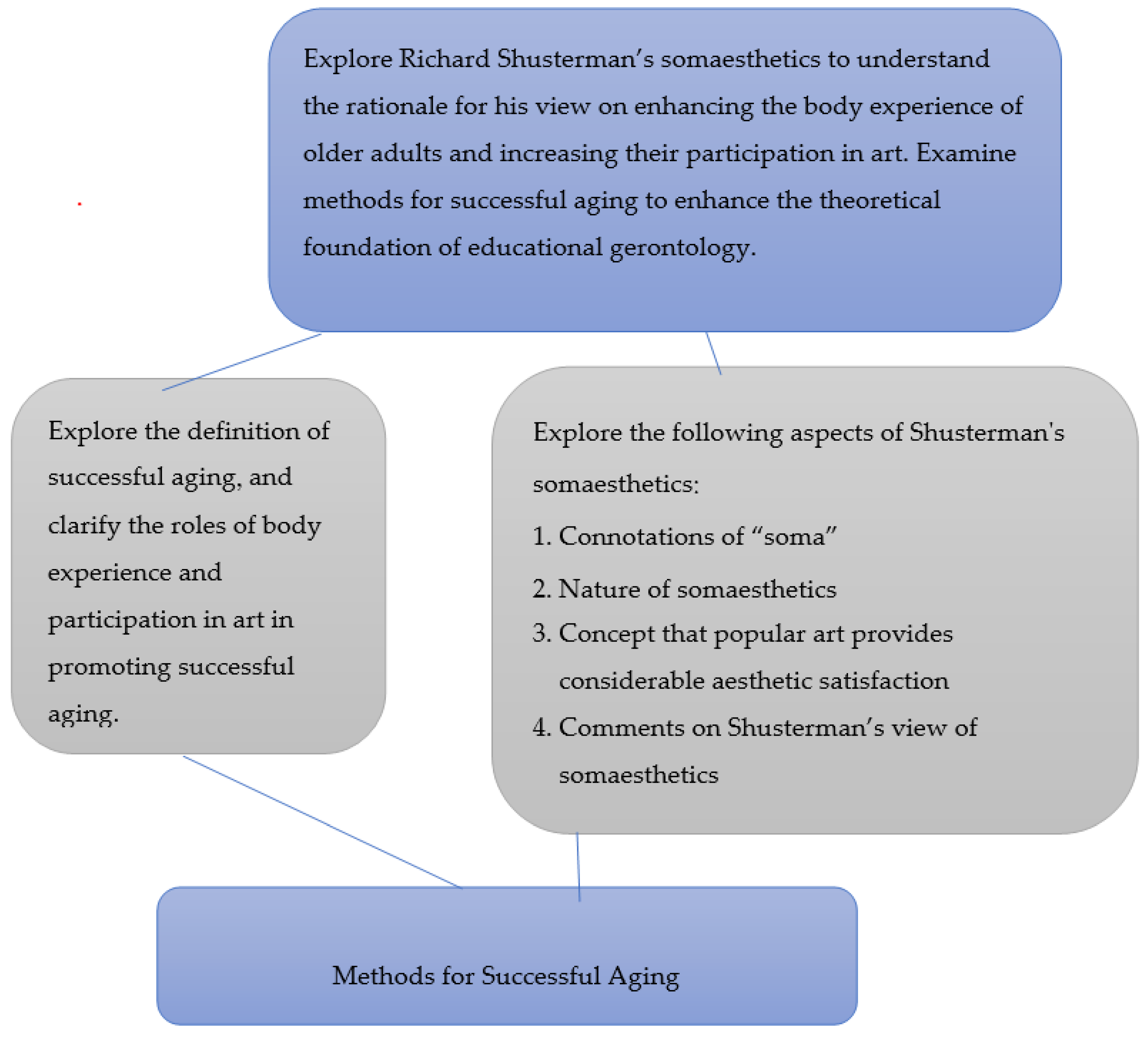

:1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

3. Definition of Successful Aging

4. Body Experience and Participation in Art Can Promote Successful Aging

5. Shusterman’s Somaesthetics

5.1. Connotations of “Soma”

5.1.1. Use of “Soma” to Describe a Sensitive Body Full of Life and Emotions

5.1.2. The Body as the Basic Medium for Human–Environment Interactions

5.1.3. Actions Are Conducted through the Body

5.1.4. Inquiry, Attention, and Improvements Related to the Body as the Core of Philosophy

5.2. Nature of Somaesthetics

5.2.1. Somaesthetics Involves Criticism and Improvement

5.2.2. Somaesthetics as an Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Practical Activity

5.2.3. Aesthetic Experience from the Perspective of Somaesthetics

Life as Aesthetics

Aesthetic Experience as an Elevated, Meaningful, and Valuable Phenomenological Experience

Enhancing and Preserving the Body by Increasing Frequency of Aesthetic Experiences

Dual Function of Aesthetics in Somaesthetics

5.3. Popular Art Provides Considerable Aesthetic Satisfaction

5.4. Comments on Shusterman’s View of Somaesthetics

5.4.1. Condemnation of the Body

Intense Emotions and Bodily Misbehaviors Affect Attention

Body as a Simple Tool

Body as the Cage of the Soul

5.4.2. Comments on Shusterman’s Somaesthetics

6. Methods for Successful Aging Derived from Shusterman’s Somaesthetics

6.1. Shifting Focus of Successful Aging to the Bodies of Older Adults

6.2. Cultivating Older Adults’ Body Consciousness Enables Them to Understand Themselves and Pursue Virtue, Happiness, and Justice

6.3. Popular Art Can Be Integrated to Promote the Aesthetic Sensibilities of Older Adults and Encourage Their Physical Participation in the Aesthetic Process

6.4. Older Adult Education Should Cultivate the Somaesthetic Sensitivity of Older Adults

6.5. Older Adult Education Should Incorporate the Physical Training of Older Adults to Help Them Enhance Their Self-Cultivation and Care for Their Body, Cultivate Virtue, and Live a Better Life

6.6. Older Adult Education Should Integrate the Body and Mind of Older Adults

7. Reflections and Conclusions

7.1. Reflections

7.2. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Oral Health Care for the Elderly and Patients with Chronic Diseases-Oral Clinic Textbook; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei City, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. The structure of successful aging. In Successful Aging; Rowe, J.W., Kahn, R.L., Eds.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. World Health Organization. 2002. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67215 (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, M.R.; Parker, M.W.; Achenbaum, W.A.; Larimore, W.L.; Koenig, H.G. Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging revisited: Positive spirituality-the forgotten facto. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikström, B.-M. Older adults and the arts: The importance of aesthetic forms of expression in later life. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2004, 30, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.; Lawton, P.H.; Manifold, M. Art education for older adults: Rationale, issues, and strategies. Int. J. Lifelong Learn. Art Educ. 2020, 3, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusterman, R. Performing Live: Aesthetic Alternatives for the Ends of Art; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Body Consciousness: A Philosophy of Mindfulness and Somaesthetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Thinking through the Body: Essays in Somaesthetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Body and the arts: The need for somaesthetics. Diogenes 2013, 59, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.L. A Study on Shusterman’s New Pragmatic Aesthetics; Jinan University Press: Jinan, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Somaesthetics: A disciplinary proposal. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1999, 57, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusterman, R. Introduction. In The Range of Pragmatism and the Limits of Philosophy; Shusterman, R., Ed.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Pragmatism and East-Asian thougt. In The Range of Pragmatism and the Limits of Philosophy; Shusterman, R., Ed.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman, R. Pragmatist Aesthetics: Living Beauty, Rethinking Art; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, J.; Dadswell, A. The role of religion, spirituality and/or belief in positive ageing for older adults. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.H. Investigating the aesthetic domain of the “Early Childhood Education and Care Curriculum Framework” for young students in Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.H. Teaching principles for aesthetic education: Cultivating Taiwanese children’s aesthetic literacy. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 8, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.H. Exploring F. W. Parker’s notions regarding child education. Policy Futures Educ. 2022, 20, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, M. Philosophy as a method: Tracing the histories of intersections of ‘philosophy’, ‘methodology’ and ‘education’. Qual. Inq. 2021, 27, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2004–2005. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2004/compendia/statab/124ed.html (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Wolfe, N.S. The Relationship between Successful Aging and Older Adult’s Participation in Higher Education Programs. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1990. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, T.D. The Relationship between Death Awareness and Successful Aging among Older Adults. Ph.D. Thesis, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2001. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Udomratn, P.; Nakawiro, D. Positive psychiatry and cognitive interventions for the elderly. Taiwan. J. Psychiatry 2016, 30, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging. Cognitive Health and Older Adults. 2022. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/cognitive-health-and-older-adults (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Shusterman, R. Practicing Philosophy: Pragmatism and the Philosophical Life; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Urtamo Annele, K.; Satu, J.; Strandberg Timo, E. Definitions of successful ageing: A brief review of a multidimensional concept. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, H.Y.; Lin, L.J. Quality of life in older adults: Benefits from the productive engagement in physical activity. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2018, 16, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergland, A.; Fougner, M.; Lund, A.; Debesay, J. Ageing and exercise: Building body capital in old age. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2022, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanning, M.; Schlicht, W. A bio-psycho-social model of successful aging as shown through the variable “physical activity”. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.D. Research on creativity and aging: The positive impact of the arts on health and illness. Generations 2006, 30, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, K.D.; O’Rourke, H.M.; Wiens, H.; Lai, J.; Howell, C.; Brett-MacLean, P. A scoping review of research on the arts, aging, and quality of life. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, B.; de Kock, L.; Liu, Y.; Dedding, C.; Schrijver, J.; Teunissen, T.; van Hartingsveldt, M.; Menderink, J.; Lengams, Y.; Lindenberg, J.; et al. The Value of Active Arts Engagement on Health and Well-Being of Older Adults: A Nation-Wide Participatory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Endowment for the Arts. The Arts and Human Development: Framing a National Research Agenda for the Arts, Lifelong Learning, and Individual Well-Being; National Endowment for the Arts: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bagan, B. Aging: What’s Art Got to Do with It? 2022. Available online: https://www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/news/ex_082809_03.shtml (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Shusterman, R. Somaesthetics. 2022. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/somaesthetics (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Wei, S.X. Body Turning and the Transformation of Aesthetics-Shusterman’s Body Aesthetics Outline; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, R.Y.; Chen, H.C. Exploring deconstruction and its implications for aesthetic education. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2016, 61, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C. Shusterman’s ‘embodied’ turn and aesthetic transformation. Chin. Lang. Lit. Study 2015, 2, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Fiala, J. Somaesthetics and embodied dance appreciation: A multisensory approach. Diálogos Arte 2019, 9, 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.R. Preface. In Shusterman’s New Pragmatic Aesthetics Research; Liu, D.L., Ed.; Jinan University Press: Jinan, China, 2012; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.P. Body aesthetic in Lucian Freuds work and Its implications for life education. Contemp. Educ. Res. Q. 2013, 21, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusterman, R. Surface & Depth: Dialectics of Criticism and Culture; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, H.; Claire, D.; O’Neill, D. Hospitalization and aesthetic health in older adults. Comp. Study 2016, 16, 173.E11–173.E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.B. Interpretation of body aesthetics. Body Cult. J. 2008, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, P. Health and Wellbeing in Late Life: Perspectives and Narratives from India; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anton, S.A.; Woods, A.J.; Ashizawa, T.; Barb, D.; Buford, T.W.; Carter, C.S.; Clark, D.J.; Cohen, R.A.; Corbett, D.B.; Cruz-Almeida, Y.; et al. Successful aging: Advancing the science of physical independence in older adults. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 24, 304–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hathorn, K. The Role of Visual Art in Improving Quality of Life Related Outcomes for Older Adults. 2022. Available online: https://www.chinatimes.com/realtimenews/20210425003168-260405?chdtv (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Hwang, P.W.; Braun, K.L. The effectiveness of dance interventions to improve older adults’ health: A systematic literature review. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2015, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Douka, S.; Zilidou, V.I.; Lilou, O.; Manou, V. Traditional dance improves the physical fitness and well-being of the elderly. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Tur, L. Fostering well-being in the elderly: Translating theories on positive aging to practical approaches. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 517226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Zhao, G.T. Body consciousness, physical training and self care: Based on Shusterman’s somaesthetics. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2016, 38, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Talia Welsh Philosophy as self-transformation: Shusterman’s somaesthetics and dependent bodies. J. Specul. Philos. 2014, 28, 489–504. [CrossRef]

- Formosa, M. Educational Gerontology. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Gu, D., Dupre, M.E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, J.; Elizabeth, A.R. Everyday learning in later life through engagement in physical activity. Educ. Gerontol. 2021, 47, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteet, J.R.; Zaben, F.A.; Koenig, H.G. Integrate spirituality into the care of older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, D.R.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Wolosin, R.J. Addressing spiritual needs and overall satisfaction with service provision among older hospitalized inpatients. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 374–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Janssen, K.; DeCelle, S. Alexander technique and Feldenkrais method: A critical overview. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 15, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, A.-K.; Schmidt-Hertha, B. Intergenerational relationships and lifelong learning. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2017, 15, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narushima, M.; Liu, J.; Diestelkamp, N. Lifelong learning in active ageing discourse: Its conserving effect on wellbeing, health and vulnerability. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 651–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- De Guzman, A.B.; Laguilles-Villafuertes, S. Understanding getting and growing older from songs of yesteryears: A latent content analysis. Educ. Gerontol. 2021, 47, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shih, Y.-H. Methods for Successful Aging: An Aesthetics-Oriented Perspective Derived from Richard Shusterman’s Somaesthetics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811404

Shih Y-H. Methods for Successful Aging: An Aesthetics-Oriented Perspective Derived from Richard Shusterman’s Somaesthetics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811404

Chicago/Turabian StyleShih, Yi-Huang. 2022. "Methods for Successful Aging: An Aesthetics-Oriented Perspective Derived from Richard Shusterman’s Somaesthetics" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811404

APA StyleShih, Y.-H. (2022). Methods for Successful Aging: An Aesthetics-Oriented Perspective Derived from Richard Shusterman’s Somaesthetics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811404