Proactive Criminal Thinking and Restrictive Deterrence: A Pathway to Future Offending and Sanction Avoidance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

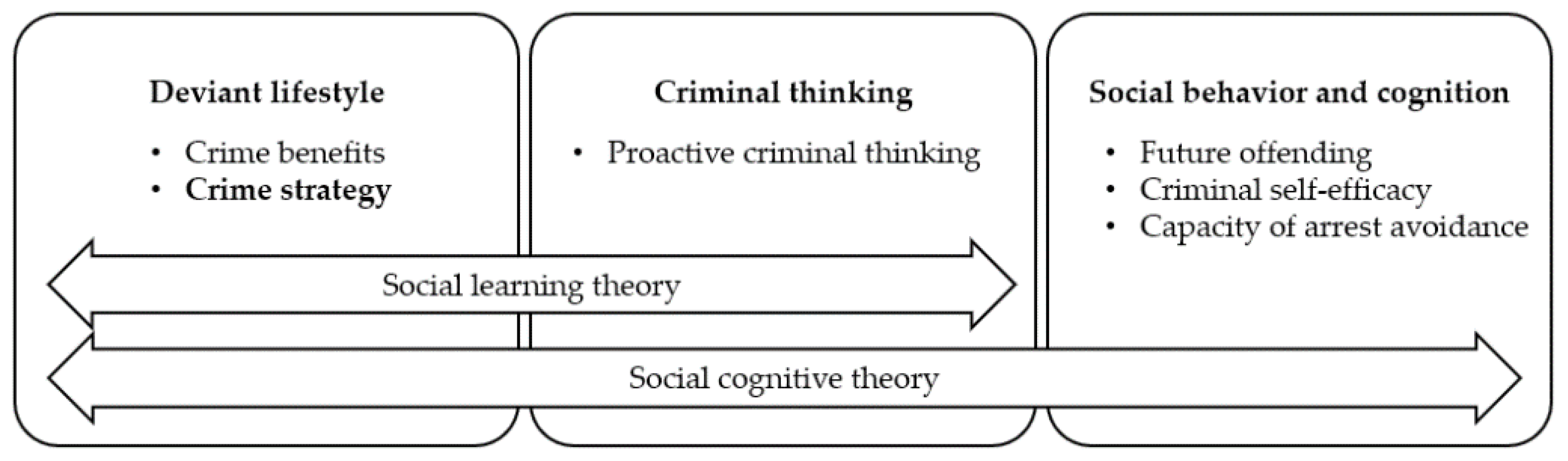

1.1. Criminal Thinking and Future Offending

1.2. Restrictive Deterrence and Future Offending

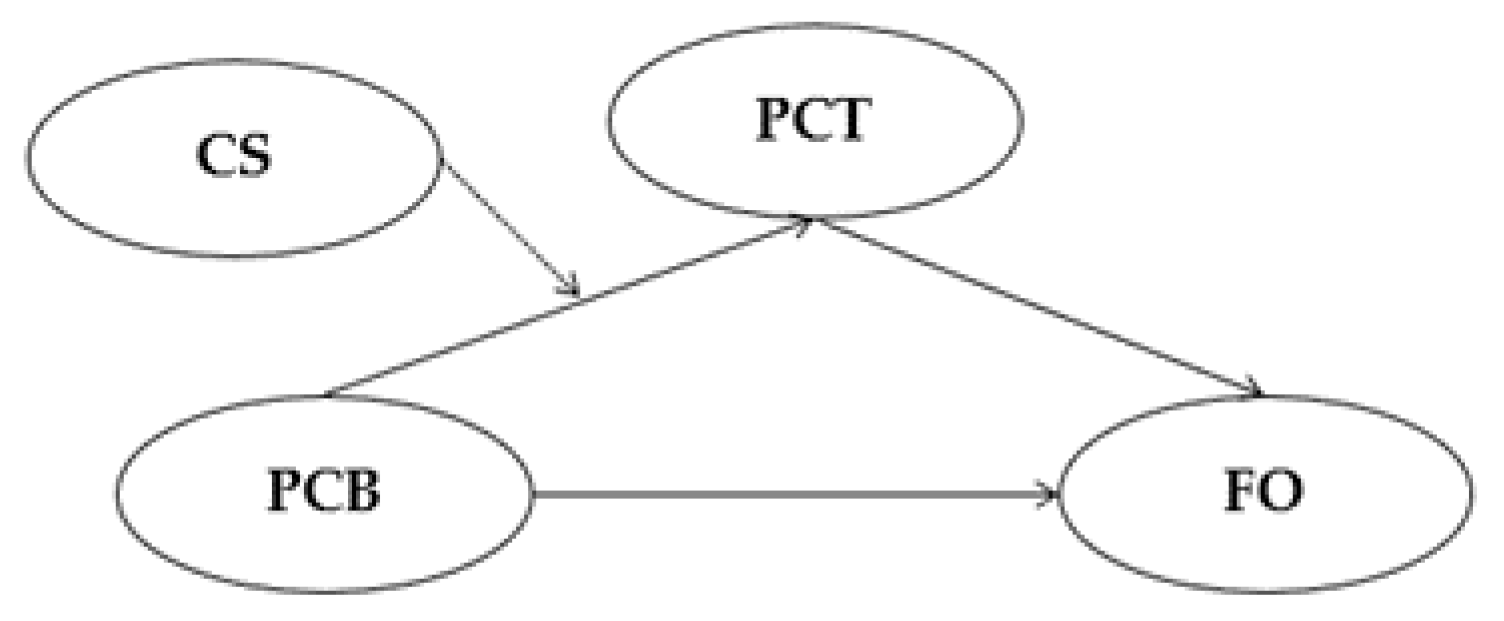

1.3. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Independent Variable

2.2.2. Mediator Variable

2.2.3. Dependent Variable

2.2.4. Moderator Variable

2.2.5. Control Variable

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Analysis

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.3. Mediation and Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacobs, B.A. Deterrence and deterrability. Criminology 2010, 48, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Psychological inertia revisited: Replicating and extending the differential effect of proactive and reactive criminal thinking on crime continuity. Deviant Behav. 2019, 40, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Proactive and reactive criminal thinking, psychological inertia, and the crime continuity conundrum. J. Crim. Justice 2016, 46, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, D.B.; Clarke, R.V.G. Chapter 1 Introduction. In The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending; Cornish, D.B., Clarke, R.V.G., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development; Kurtines, W.M., Gewirtz, J.L., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 45–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, G.M.; Matza, D. Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, G.D. Crime and social cognition: A meta-analytic review of the developmental roots of adult criminal thinking. J. Exp. Criminol. 2020, 18, 183–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Crime in a Psychological Context: From Career Criminals to Criminal Careers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlyn, B.; Maxwell, C.; Hales, J.; Tait, C. Crime and justice survey (England and Wales) technical report. Lond. Home Off. Natcen BMRB 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, D.; Jakob-Chien, C. Contemporaneous co-occurrence of serious and violent juvenile offending and other problem behaviors. In Serious & Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions; Loeber, R., Farrington, D.P., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, G.D.; Yurvati, E. Testing the construct validity of the PICTS proactive and reactive scores against six putative measures of proactive and reactive criminal thinking. Psychol. Crime Law 2017, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Changes in criminal thinking and identity in novice and experienced inmates: Prisonization revisited. Crim. Justice Behav. 2003, 30, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Crime continuity and psychological inertia: Testing the cognitive mediation and additive postulates with male adjudicated delinquents. J. Quant. Criminol. 2016, 32, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Proactive criminal thinking and deviant identity as mediators of the peer influence effect. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2017, 15, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.C.O.; Lo, T.W.; Zhong, L.Y.; Chui, W.H. Criminal recidivism of incarcerated male nonviolent offenders in Hong Kong. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2015, 59, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.C.O.; Lo, T.W.; Zhong, L.Y. Identifying the self-anticipated reoffending risk factors of incarcerated male repeat offenders in Hong Kong. Prison J. 2016, 96, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.W. Triadization of youth gangs in Hong Kong. Br. J. Criminol. 2012, 52, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Gang influence: Mediating the gang–delinquency relationship with proactive criminal thinking. Crim. Justice Behav. 2019, 46, 1044–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Criminal thinking and gang affiliation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Criminol. Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 7, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Friends, cognition, and delinquency: Proactive and reactive criminal thinking as mediators of the peer influence and peer selection effects among male delinquents. Justice Q. 2016, 33, 1055–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. The sibling effect for delinquency: Mediation by proactive criminal thinking and moderation by age. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2020, 64, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Self-report measures of psychopathy, antisocial personality, and criminal lifestyle: Testing and validating a two-dimensional model. Crim. Justice Behav. 2008, 35, 1459–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Measuring proactive and reactive criminal thinking with the PICTS. J. Interpers. Violence 2007, 22, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Short-term goals and physically hedonistic values as mediators of the past-crime—Future-crime relationship. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2015, 20, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D. Applying CBT to the Criminal Thought Process. In Forensic CBT: A Handbook for Clinical Practice; Tafrate, R.C., Mitchell, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.P. Crime, Punishment, and Deterrence; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, B.A. Crack dealers’ apprehension avoidance techniques: A case of restrictive deterrence. Justice Q. 1996, 13, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T.; Hough, M. Illegal dealings: The impact of low-level police enforcement on drug markets. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2001, 9, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, D.; Strang, J.; Beswick, T.; Gossop, M. Assessment of a concentrated, high-profile police operation. No discernible impact on drug availability, price or purity. Br. J. Criminol. 2001, 41, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.E.; Moxham-Hall, V.; Ritter, A.; Weatherburn, D.; MacCoun, R. The deterrent effects of Australian street-level drug law enforcement on illicit drug offending at outdoor music festivals. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 41, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Lo, T.W. Restrictive deterrence in drug offenses: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of mixed studies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.A.; Miller, J. Crack dealing, gender, and arrest avoidance. Soc. Probl. 1998, 45, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbonneau, M.; Copes, H. Drive it like you stole it: Auto theft and the illusion of normalcy. Br. J. Criminol. 2006, 46, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, E.; Bouchard, M. Cleaning up your act: Forensic awareness as a detection avoidance strategy. J. Crim. Justice 2010, 38, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallupe, O.; Bouchard, M.; Caulkins, J.P. No change is a good change? Restrictive deterrence in illegal drug markets. J. Crim. Justice 2011, 39, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.A.; Cherbonneau, M. Auto theft and restrictive deterrence. Justice Q. 2014, 31, 344–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimon, D.; Alper, M.; Sobesto, B.; Cukier, M. Restrictive deterrent effects of a warning banner in an attacked computer system. Criminology 2014, 52, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.; Maimon, D.; Sobesto, B.; Cukier, M. The effect of a surveillance banner in an attacked computer system: Additional evidence for the relevance of restrictive deterrence in cyberspace. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2015, 52, 829–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, K.; Copes, H.; Hochstetler, A. Advancing restrictive deterrence: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Crim. Justice 2016, 46, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. J. Polit. Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, S.; Allen, A. Bentham’s sanction typology and restrictive deterrence: A study of young, suburban, middle-class drug dealers. J. Drug Issues 2014, 44, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.C.; Warr, M. A reconceptualization of general and specific deterrence. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1993, 30, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternoster, R. Absolute and restrictive deterrence in a panel of youth: Explaining the onset, persistence/desistance, and frequency of delinquent offending. Soc. Probl. 1989, 36, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejong, C. Survival analysis and specific deterrence: Integrating theoretical and empirical models of recidivism. Criminology 1997, 35, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shover, N. Age, differential expectations, and crime desistance. Criminology 1992, 30, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Malm, A.; Bouchard, M. Production, perceptions, and punishment: Restrictive deterrence in the context of cannabis cultivation. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, B.A.; Cherbonneau, M. Perceived sanction threats and projective risk sensitivity: Auto theft, carjacking, and the channeling effect. Justice Q. 2018, 35, 191–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitaille, C. À qui profite le crime? Les facteurs individuels de la réussite criminelle. Criminologie 2005, 37, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, L.; Le Blanc, M. Differential cost avoidance and successful criminal careers: Random or rational? Crime Delinq. 2007, 53, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, B.; Fischer, M. Naming oneself criminal: Gender difference in offenders’ identity negotiation. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2005, 49, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezina, T.; Topalli, V. Criminal self-efficacy: Exploring the correlates and consequences of a “successful criminal” identity. Crim. Justice Behav. 2012, 39, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nee, C.; Ward, T. Review of expertise and its general implications for correctional psychology and criminology. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalli, V. Criminal expertise and offender decision-making: An experimental analysis of how offenders and non-offenders differentially perceive social stimuli. Br. J. Criminol. 2004, 45, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, K.L.; Bargh, J.A.; Garcia, M.; Chaiken, S. The automatic evaluation of novel stimuli. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T. Seeing the past in the present: The effect of associations to familiar events on judgments and decisions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Loughran, T.A. Testing a Bayesian learning theory of deterrence among serious juvenile offenders. Criminology 2011, 49, 667–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, B.; Englefield, A.; Denleyy, J. I heard it through the grapevine: A randomized controlled trial on the direct and vicarious effects of preventative specific deterrence initiatives in criminal networks. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 2019, 109, 819–868. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, A.A.; Apel, R.; Welsh, B.C. The spillover effects of focused deterrence on gang violence. Eval. Rev. 2013, 37, 314–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand Corporation. Survey of Jail and Prison Inmates, 1978: California, Michigan, Texas; Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crank, B.R.; Brezina, T. “Prison will either make ya or break ya”: Punishment, deterrence, and the criminal lifestyle. Deviant Behav. 2013, 34, 782–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumstein, A.; Cohen, J.; Piquero, A.R.; Visher, C.A. Linking the crime and arrest processes to measure variations in individual arrest risk per crime (Q). J. Quant. Criminol. 2010, 26, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, R.R.; Cohen, I.M.; Glackman, W.; Odgers, C. Serious and violent young offenders’ decisions to recidivate: An assessment of five sentencing models. Crime Delinq. 2003, 49, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumminello, M.; Edling, C.; Liljeros, F.; Mantegna, R.N.; Sarnecki, J. The phenomenology of specialization of criminal suspects. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S. Offending: Drug-related expertise and decision making. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 20, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, T.; Small, W.; Johnston, C.; Li, K.; Montaner, J.S.G.; Wood, E. Characteristics of injection drug users who participate in drug dealing: Implications for drug policy. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2008, 40, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.G.; Latkin, C.A. Drug users’ involvement in the drug economy: Implications for harm reduction and hiv prevention programs. J. Urban Health 2002, 79, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, K.; Broc, G. Structural Equation Modeling with Lavaan; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: London, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T.D.; Bovaird, J.A.; Widaman, K.F. On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2006, 13, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternoster, R.; Pogarsky, G. Rational choice, agency and thoughtfully reflective decision making: The short and long-term consequences of making good choices. J. Quant. Criminol. 2009, 25, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D.; DeLisi, M. Antisocial cognition and crime continuity: Cognitive mediation of the past crime-future crime relationship. J. Crim. Justice 2013, 41, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Judd, C.M. Power anomalies in testing mediation. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Quitters never win: The (adverse) incentive effects of competing with superstars. J. Polit. Econ. 2011, 119, 982–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, K.; Prakash, N. Cycling to school: Increasing secondary school enrollment for girls in India. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2017, 9, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Zingales, L. Financial dependence and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 559–586. [Google Scholar]

- So, C.K. The Social Capital of Young Drug User-Dealers amid the Changing Drug Market in Hong Kong. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grundetjern, H.; Sandberg, S. Dealing with a gendered economy: Female drug dealers and street capital. Eur. J. Criminol. 2012, 9, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L.; Kavanaugh, P.R. Women’s evolving roles in drug trafficking in the United States: New conceptualizations needed for 21st-century markets. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2017, 44, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. Marijuana Use Hits Record High in New Gallup Poll. Available online: https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/3618903-marijuana-use-hits-record-high-in-new-gallup-poll/ (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N. Valid | %/ Mean (Std. Dev, Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 832 | 25.448 (6.64, 14–60) |

| Race | 829 | |

| Asian | 4 | 0.50% |

| Black | 310 | 37.40% |

| Chicano/Latino | 95 | 11.50% |

| Indian/Native American | 9 | 1.10% |

| White | 395 | 47.60% |

| Other | 16 | 1.90% |

| Education | 834 | |

| No schooling | 3 | 0.40% |

| 6th grade or less | 22 | 2.60% |

| 7th–9th grade | 121 | 14.50% |

| 10th–11th grade | 298 | 35.70% |

| High school grade | 165 | 19.80% |

| Some college | 206 | 24.70% |

| College graduate | 15 | 1.80% |

| Post-graduate study | 4 | 0.50% |

| Marriage | 826 | |

| Married | 147 | 17.80% |

| Widowed | 12 | 1.50% |

| Divorced | 116 | 14% |

| Separated | 60 | 7.30% |

| Never married | 491 | 59.40% |

| Experience in drug dealing * | 850 | |

| Committed drug dealing in WP3 only | 266 | 31.30% |

| Committed drug dealing in WP3 and WP2 or WP1 | 219 | 25.80% |

| Committed drug dealing in WP3, WP2, and WP1 | 365 | 42.90% |

| Frequency of drug dealing | 850 | 2.326 (1.76, 0–4) |

| Self-identity as a drug dealer | 831 | |

| No | 432 | 52% |

| Yes | 399 | 48% |

| Current incarceration for drug dealing | 820 | |

| No | 705 | 86% |

| Yes | 115 | 14% |

| No. of arrests for drug dealing | 800 | 0.489 (1, 0–8) |

| No. of crime types | 850 | 2.951 (2.24, 0–9) |

| No. of property crimes | 850 | 2.392 (1.85, 0–7) |

| No. of violent crimes | 850 | 0.559 (0.68, 0–2) |

| Length of WP3 (months) | 841 | 14.432 (5.57, 1–25) |

| Model Fit Indices | Covariance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA model | Chi-square | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | PCB | CS | FO | CSE | AA |

| Structure model | 617.352 | 360 | 0.948 | 0.941 | 0.034 | 0.04 | |||||

| PPCT | 42.177 | 24 | 0.965 | 0.947 | 0.034 | 0.04 | 0.389 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.549 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.307 *** |

| PCB | 52.478 | 12 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.046 | 0.258 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.358 *** | 0.268 *** | |

| CS | 133.974 | 35 | 0.955 | 0.942 | 0.078 | 0.039 | 0.193 *** | 0.265 *** | 0.301 *** | ||

| FO | 0.194 *** | 0.336 *** | |||||||||

| CSE | 0.367 *** | ||||||||||

| Pathways | BCBCI | Type of Mediation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Lower | Upper | ||

| FO (outcome measure) | Full mediation | |||

| PCB → FO (Direct effect) | −0.108 | −0.339 | 0.555 | |

| PCB → PCT → FO (Indirect effect) | 0.583 | 0.252 | 0.914 | |

| CSE (outcome measure) | Partial mediation | |||

| PCB → CSE (Direct effect) | 0.242 | 0.109 | 0.375 | |

| PCB → PCT → CSE (Indirect effect) | 0.108 | 0.024 | 0.193 | |

| AA (outcome measure) | Partial mediation | |||

| PCB → AA (Direct effect) | 0.116 | 0.05 | 0.182 | |

| PCB → PCT → CSE → AA (Indirect effect) | 0.044 | 0.013 | 0.075 | |

| Pathways | Drug Dealer (n = 850) | Less-Experienced Group (n = 485) | Experienced Group (n = 365) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCBCI | BCBCI | BCBCI | |||||||

| β | Lower | Upper | β | Lower | Upper | β | Lower | Upper | |

| PCT (outcome measure) | |||||||||

| PCB (predictor) | 0.161 | 0.076 | 0.246 | 0.1 | 0.009 | 0.192 | 0.24 | 0.096 | 0.385 |

| CS (moderator) | 0.061 | 0.026 | 0.097 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.087 | 0.073 | 0.015 | 0.132 |

| PCB_CS (interactor) * | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.008 | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.031 | 0.005 | 0.056 |

| PCB → PCT → FO | |||||||||

| mean(CS) − 1SD | 0.754 | 0.335 | 1.173 | 0.460 | 0.088 | 0.833 | 1.246 | 0.185 | 2.307 |

| mean(CS) | 0.814 | 0.380 | 1.248 | 0.486 | 0.104 | 0.868 | 1.368 | 0.251 | 2.486 |

| mean(CS) + 1SD | 0.874 | 0.420 | 1.328 | 0.512 | 0.115 | 0.909 | 1.490 | 0.309 | 2.671 |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.079 | 0.012 | 0.147 | 0.036 | −0.029 | 0.101 | 0.157 | 0.021 | 0.292 |

| PCB → PCT → CSE | |||||||||

| mean(CS) − 1SD | 0.023 | 0.084 | 0.363 | 0.213 | 0.013 | 0.413 | 0.251 | 0.024 | 0.477 |

| mean(CS) | 0.246 | 0.099 | 0.392 | 0.229 | 0.023 | 0.435 | 0.283 | 0.037 | 0.529 |

| mean(CS) + 1SD | 0.268 | 0.113 | 0.423 | 0.224 | 0.031 | 0.458 | 0.315 | 0.048 | 0.582 |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.03 | 0.007 | 0.052 | 0.022 | −0.001 | 0.054 | 0.041 | 0.005 | 0.077 |

| PCB → PCT → CSE → AA | |||||||||

| mean(CS) − 1SD | 0.118 | 0.058 | 0.177 | 0.106 | 0.028 | 0.185 | 0.161 | 0.049 | 0.272 |

| mean(CS) | 0.129 | 0.067 | 0..191 | 0.113 | 0.033 | 0.192 | 0.182 | 0.063 | 0.302 |

| mean(CS) + 1SD | 0.140 | 0.075 | 0.205 | 0.119 | 0.037 | 0.2 | 0.204 | 0.075 | 0.333 |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.025 | 0.009 | −0.005 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.045 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, X.; Lo, T.W. Proactive Criminal Thinking and Restrictive Deterrence: A Pathway to Future Offending and Sanction Avoidance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811636

Guan X, Lo TW. Proactive Criminal Thinking and Restrictive Deterrence: A Pathway to Future Offending and Sanction Avoidance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811636

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Xin, and T. Wing Lo. 2022. "Proactive Criminal Thinking and Restrictive Deterrence: A Pathway to Future Offending and Sanction Avoidance" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811636

APA StyleGuan, X., & Lo, T. W. (2022). Proactive Criminal Thinking and Restrictive Deterrence: A Pathway to Future Offending and Sanction Avoidance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811636