Health Education about Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors in Gynecological and Obstetric Care: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Providers’ Views in Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

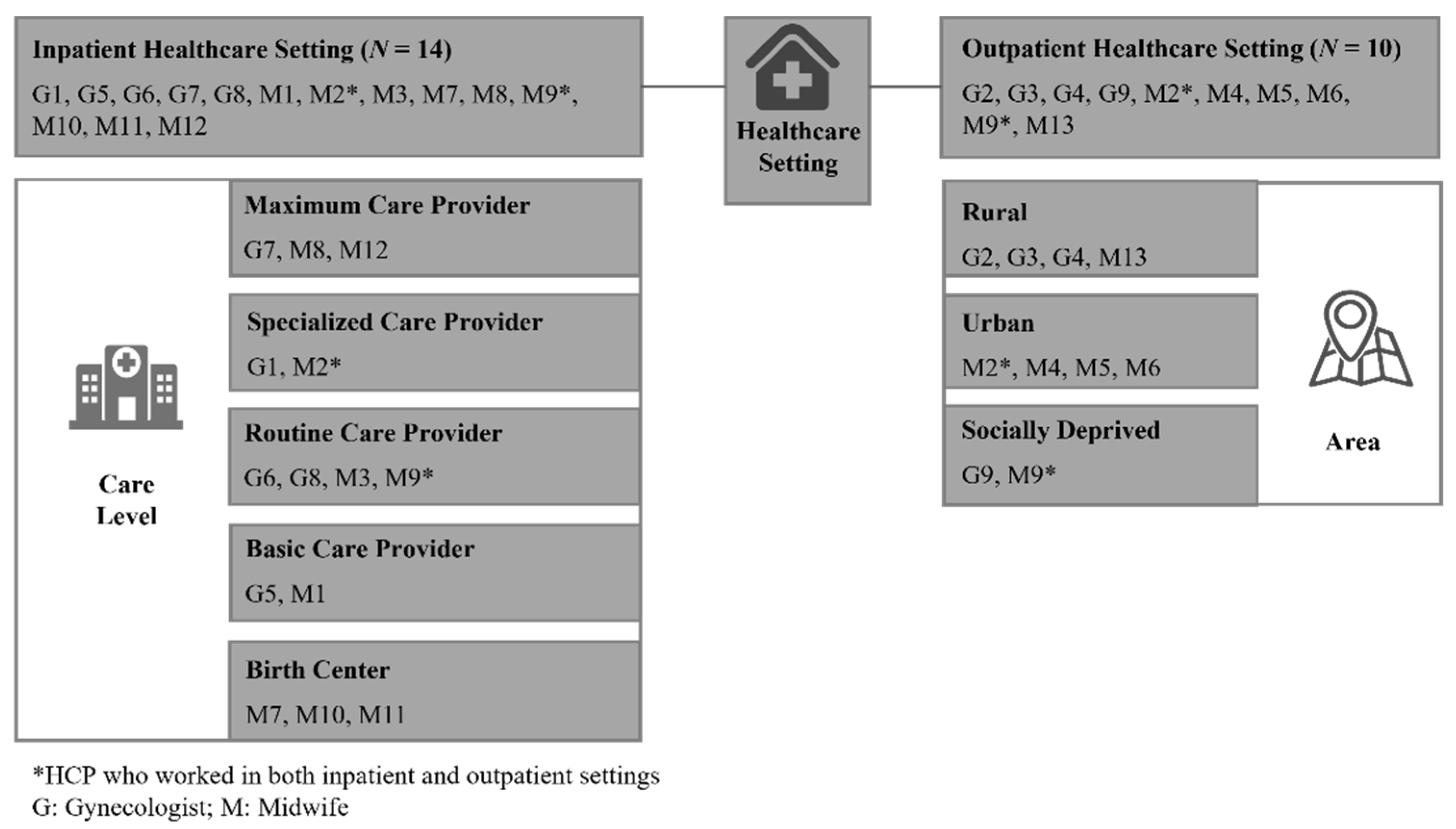

2.2. Study Population, Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Key Findings

Health Education during Pregnancy and Lactation on LRRFs in Gynecological and Obstetric Care

3.2. Causal Conditions

3.2.1. Medical History and Specific Needs

“If I have a woman in treatment and I ask during anamnesis for her experience with alcohol, drugs, and smoking and she denies everything and I have the impression that she is telling me the truth, then I don’t start to educate her that smoking is bad.”(M5)

“So, we offer a consultation for at-risk patients who come specifically with a question or a pre-history. Therefore, we are very oriented to the specific problem at hand.”(G7)

“So, I always offer an additional appointment to a woman so that if she has any complaints she can come back and we can work on the issue then.”(M13)

“If a pregnant woman has no problems, is content and happy, then I do not need to educate her much.”(G9)

3.2.2. Socioeconomic Status

“There is the teacher who smoked occasionally and stops as soon as she is pregnant [whereas] the less-educated patients always come up with a standard argument, such as that the child might go into withdrawal.”(G3)

“What I notice quite clearly, again and again, is: the more intelligent, the richer, the more distinguished the people, the more the alcohol is concealed. So, this very simple-minded woman tells me much sooner that she has eaten half a box of Mon Chéri [liquor-filled confectionery] than the well-off factory owner’s wife who likes to drink her glass of wine in the evening.”(M7)

3.2.3. Migration Background

“So, culturally, it depends very much on where the women come from, also in terms of smoking. African women smoke very little, maybe they smoke pot, but they don’t smoke cigarettes, but they drink more alcohol. […] if I have a Russian family for example, it’s completely normal that vodka is already poured out in the morning. It depends a bit on where the women come from, whether they drink or not, but during pregnancy they usually don’t, unless they have an addiction problem.”(M7)

3.3. Context

“We don’t do that. So, we don’t do any education there.”(G7)

“I then hold information evenings and 100 people come. So usually, the women come with their husbands. And the danger of alcohol consumption during pregnancy takes up a large part. When they go home, they all understand that. I then also say that everything else is to be reiterated.”(G1)

“Well, I do relatively little [laughs] education in pregnancy. I work in the delivery room, where women usually give birth.”(M8)

3.3.1. Date of Initial Consultation

3.3.2. Time taken

“I always take time for the pregnant women [...] sometimes it’s longer, sometimes it’s a little less time.”(G2)

“So, I can’t do much on the subject myself, sometimes because of my own time pressure.”(M2)

3.4. Intervening Conditions

3.4.1. Lack of Standardized Guidelines

“I actually have to pass. […] I don’t know if there are really any guidelines.”(M12)

“The doctor and midwife have to educate […], but to the questions of “How to do this?”, “How to address it?”, and “How to get information?” […] there are no in-depth instructions.”(M11)

3.4.2. Unfavorable Regulations

“Actually, you wouldn’t have any time for it during the puerperium. Because the puerperium is very strictly regulated in terms of payment, technically covering only 20–30 min […] what is more, I don’t get paid; that’s my personal service.”(M9)

3.4.3. Unclear Assignment of Responsibility

“There is a specialist […], another counseling center […]. Because that would go beyond my scope.”(M4)

“Basically, this is one of the important topics that should take place in the gynecological practice as well as in midwifery care, … but unfortunately I don’t know if it is included in every gynecological practice.”(M12)

3.5. Action Strategies

3.5.1. Demand-Driven Healthcare Approach

“I’d rather give her advice on how to reduce smoking so that she doesn’t have a guilty conscience, because this will bother her even more.”(M10)

“When we see someone in preterm labor, this is also explicitly addressed with the request either that we take this stress factor out of the equation by admitting the women as inpatients, or I sometimes tell the women to take it down a notch.”(G8)

3.5.2. Differentiation between Health Education during Pregnancy and Lactation

“I would say they are similar in terms of addiction and such stuff.”(M3)

“So, I tell them that they should rather smoke and breastfeed because breastfeeding is very important.”(G8)

3.6. Consequences of Current Practice

3.6.1. Pre-Conception Education of Women on LRRFs

3.6.2. Support from Further Health Organizations

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Discussion of the Key Findings

4.3. Potential Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ulrich, F.; Petermann, F. Consequences and Possible Predictors of Health-damaging Behaviors and Mental Health Problems in Pregnancy—A Review. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2016, 76, 1136–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, J.; Berg, M.; Dencker, A.; Olander, E.K.; Begley, C. Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy, for the mother and baby: A systematic review of reviews. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, T.; Chen, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, T.; Chen, L.; Ye, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Qin, J. Parental alcohol consumption and the risk of congenital heart diseases in offspring: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundermann, A.C.; Zhao, S.; Young, C.L.; Lam, L.; Jones, S.H.; Velez Edwards, D.R.; Hartmann, K.E. Alcohol Use in Pregnancy and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 1606–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Schulte, E.; Kurlemann, G.; Harder, A. Tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs during pregnancy and risk of neuroblastoma: Systematic review. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018, 103, F467–F473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marufu, T.C.; Ahankari, A.; Coleman, T.; Lewis, S. Maternal smoking and the risk of still birth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Pereira, P.P.S.; Da Mata, F.A.F.; Figueiredo, A.C.G.; Andrade, K.R.C.d.; Pereira, M.G. Maternal Active Smoking During Pregnancy and Low Birth Weight in the Americas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayfield, S.; Plugge, E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between maternal smoking in pregnancy and childhood overweight and obesity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzi, C.; Saunders, D.H.; Linton, K.; Norman, J.E.; Reynolds, R.M. Sedentary behaviours during pregnancy: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.-M.; Poitras, V.J.; Jaramillo Garcia, A.; Gray, C.E.; Barrowman, N.; Skow, R.J.; Meah, V.L.; Riske, L.; Sobierajski, F.; et al. Prenatal exercise for the prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, L.M.; Nobles, C.; Ertel, K.A.; Chasan-Taber, L.; Whitcomb, B.W. Physical activity interventions in pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresham, E.; Bisquera, A.; Byles, J.E.; Hure, A.J. Effects of dietary interventions on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Song, J.-M.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.-L.; Xin, C.-M. A meta-analysis of risk of pregnancy loss and caffeine and coffee consumption during pregnancy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2015, 130, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-W.; Wu, Y.; Neelakantan, N.; Chong, M.F.-F.; Pan, a.; van Dam, R.M. Maternal caffeine intake during pregnancy is associated with risk of low birth weight: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teshome, A.; Yitayeh, A. Relationship between periodontal disease and preterm low birth weight: Systematic review. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 24, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, K.F.; Sanghani, R.S.; Avorn, J.; Urato, A.C. Preterm birth and antidepressant medication use during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.E.; Grigoriadis, S.; Mamisashvili, L.; Vonderporten, E.H.; Roerecke, M.; Rehm, J.; Dennis, C.-L.; Koren, G.; Steiner, M.; Mousmanis, P.; et al. Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Dakkak, H.; Seabrook, J.A. Is breast best? Examining the effects of alcohol and cannabis use during lactation. J. Neonatal-Perinat. Med. 2018, 11, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.A.; Hasken, J.M.; Blankenship, J.; Marais, A.-S.; Joubert, B.; Cloete, M.; Vries, M.M.d.; Barnard, R.; Botha, I.; Roux, S.; et al. Breastfeeding and maternal alcohol use: Prevalence and effects on child outcomes and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Reprod. Toxicol. 2016, 63, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglia, R.; Binns, C. Alcohol and lactation: A systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2006, 63, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenmyer, J.R.; Popova, S.; Klug, M.G.; Burd, L. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the cost of and savings from prevention in the United States and Canada. Addiction 2020, 115, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, R.M.; Shetiya, S.H.; Agarwal, D.R.; Mitra, P.; Bomble, N.A.; Narayana, D.S. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Pregnant Women regarding Oral Health Status and Treatment Needs following Oral Health Education in Pune District of Maharashtra: A Longitudinal Hospital-based Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahri, N.; Iliati, H.R.; Sajjadi, M.; Boloochi, T.; Bahri, N. Effects of Oral and Dental Health Education Program on Knowledge, Attitude and Short-Time Practice of Pregnant Women (Mashhad-Iran). J. Mashhad Dent. Sch. 2012, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisinger, M.L.; Geurs, N.C.; Bain, J.L.; Kaur, M.; Vassilopoulos, P.J.; Cliver, S.P.; Hauth, J.C.; Reddy, M.S. Oral health education and therapy reduces gingivitis during pregnancy. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windsor, R.A.; Lowe, J.B.; Perkins, L.L.; Smith-Yoder, D.; Artz, L.; Crawford, M.; Amburgy, K.; Boyd, N.R., Jr. Health education for pregnant smokers: Its behavioral impact and cost benefit. Am. J. Public Health 1993, 83, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabro, K.; Taylor, W.C.; Kapadia, A. Pregnancy, alcohol use and the effectiveness of written health education materials. Patient Educ. Couns. 1996, 29, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford-Williams, F.; Mikocka-Walnus, A.; Esterman, A.; Steen, M. A public health intervention to change knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding alcohol consumption in pregnancy. Evid. Based Midwifery 2016, 14, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mahnaz, S.; Ashraf, K. A randomized trial to promote physical activity during pregnancy based on health belief model. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani, L.; Alipoor, M.; Amoee, S.; Keshavarzi, S. Health Promoting Behaviors and Self-efficacy of Physical Activity During Pregnancy: An Interventional Study. Int. J. Women’s Health Reprod. Sci. 2017, 5, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizán, J.M.; Barros, F.; Langer, A.; Farnot, U.; Victora, C.; Villar, J. Impact of health education during pregnancy on behavior and utilization of health resources. Latin American Network for Perinatal and Reproductive Research. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 1995, 173, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Heesterbeek, Q.; Manniën, J.; Hutton, E.K.; Brug, J.; Westerman, M.J. Exploring health education with midwives, as perceived by pregnant women in primary care: A qualitative study in the Netherlands. Midwifery 2017, 46, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeckenjan, M.; Brückner, A.; Vetter, K. Schwangerenvorsorge. Gynäkologe 2021, 54, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattern, E.; Lohmann, S.; Ayerle, G.M. Experiences and wishes of women regarding systemic aspects of midwifery care in Germany: A qualitative study with focus groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastring, D.; Mayfield-Johnson, S.; Madison, J. Evaluation of a Health Education Intervention to Improve Knowledge, Skills, Behavioral Intentions and Resources Associated with Preventable Determinants of Infant Mortality. Divers Equal Health Care 2017, 14, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Patel, S. The Effectiveness of Lactation Consultants and Lactation Counselors on Breastfeeding Outcomes. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliadou, M.; Lykeridou, K.; Prezerakos, P.; Swift, E.M.; Tziaferi, S.G. Measuring the Effectiveness of a Midwife-led Education Programme in Terms of Breastfeeding Knowledge and Self-efficacy, Attitudes Towards Breastfeeding, and Perceived Barriers of Breastfeeding Among Pregnant Women. Mater. Socio-Med. 2018, 30, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechsle, A.; Wensing, M.; Ullrich, C.; Bombana, M. Health Knowledge of Lifestyle-Related Risks during Pregnancy: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pregnant Women in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Grounded Theory: Grundlagen Qualitativer Sozial-Forschung; Beltz, Psychologie-Verlag-Union: Weinheim, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Researc; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mutterschafts-Richtlinien-Richtlinien über die ärztliche Betreuung während der Schwangerschaft und nach der Entbindung. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/62-492-1829/Mu-RL_2019-03-22_iK_2019-05-28.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Chuang, C.H.; Hwang, S.W.; McCall-Hosenfeld, J.S.; Rosenwasser, L.; Hillemeier, M.M.; Weisman, C.S. Primary care physicians′ perceptions of barriers to preventive reproductive health care in rural communities. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2012, 44, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarnall, K.S.H.; Pollak, K.I.; Østbye, T.; Krause, K.M.; Michener, J.L. Primary care: Is there enough time for prevention? Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, E.P.; Orleans, C.T.; Pender, N.; Allan, J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: An evidence-based approach. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luquis, R.R.; Paz, H.L. Attitudes about and practices of health promotion and prevention among primary care providers. Health Promot. Pract. 2015, 16, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badertscher, N.; Rossi, P.O.; Rieder, A.; Herter-Clavel, C.; Rosemann, T.; Zoller, M. Attitudes, barriers and facilitators for health promotion in the elderly in primary care. A qualitative focus group study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 142, w13606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lawrence, R.A.; McLoone, J.K.; Wakefield, C.E.; Cohn, R.J. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunath, J.; Günther, J.; Rauh, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Stecher, L.; Rosenfeld, E.; Kick, L.; Ulm, K.; Hauner, H. Effects of a lifestyle intervention during pregnancy to prevent excessive gestational weight gain in routine care-the cluster-randomised GeliS trial. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, J.; Hoffmann, J.; Kunath, J.; Spies, M.; Meyer, D.; Stecher, L.; Rosenfeld, E.; Kick, L.; Rauh, K.; Hauner, H. Effects of a Lifestyle Intervention in Routine Care on Prenatal Dietary Behavior-Findings from the Cluster-Randomized GeliS Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, J.; Hoffmann, J.; Spies, M.; Meyer, D.; Kunath, J.; Stecher, L.; Rosenfeld, E.; Kick, L.; Rauh, K.; Hauner, H. Associations between the Prenatal Diet and Neonatal Outcomes-A Secondary Analysis of the Cluster-Randomised GeliS Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. In WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koletzko, B.; Bauer, C.-P.; Cierpka, M.; Cremer, M.; Flothkötter, M.; Graf, C.; Heindl, I.; Hellmers, C.; Kersting, M.; Krawinkel, M.; et al. Ernährung und Bewegung von Säuglingen und stillenden Frauen. Mon. Kinderheilkd. 2016, 164, 771–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koletzko, B.; Cremer, M.; Flothkötter, M.; Graf, C.; Hauner, H.; Hellmers, C.; Kersting, M.; Krawinkel, M.; Przyrembel, H.; Röbl-Mathieu, M.; et al. Diet and Lifestyle Before and During Pregnancy-Practical Recommendations of the Germany-wide Healthy Start-Young Family Network. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018, 78, 1262–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Dakn, M.; Alexy, U.; Beyer, K.; Cremer, M.; Ensenauer, R.; Flothkötter, M.; Geene, R.; Hellmers, C.; Joisten, C.; Koletzko, B.; et al. Ernährung und Bewegung im Kleinkindalter. Mon. Kinderheilkd. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filby, A.; McConville, F.; Portela, A. What prevents quality midwifery care? A systematic mapping of barriers in low and middle income countries from the provider perspective. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Halcomb, E.; Desborough, J.; McInnes, S. Lifestyle risk communication by general practice nurses: An integrative literature review. Collegian 2019, 26, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramluggun, P.; Anjoyeb, M.; D′Cruz, G. Mental health nursing students′ views on their readiness to address the physical health needs of service users on registration. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 26, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, D.; Snelgrove-Clarke, E.; Campbell-Yeo, M.; Aston, M.; Helwig, M.; Baker, K.A. The experiences of midwives and nurses collaborating to provide birthing care: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2015, 13, 74–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfinder, M.; Kunst, A.E.; Feldmann, R.; van Eijsden, M.; Vrijkotte, T.G.M. Preterm birth and small for gestational age in relation to alcohol consumption during pregnancy: Stronger associations among vulnerable women? Results from two large Western-European studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Silva, M.I.; Azcorra, H.; Dickinson, F.; Bogin, B.; Frisancho, A.R. Influence of maternal stature, pregnancy age, and infant birth weight on growth during childhood in Yucatan, Mexico: A test of the intergenerational effects hypothesis. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2009, 21, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donahue, S.M.A.; Zimmerman, F.J.; Starr, J.R.; Holt, V.L. Correlates of pre-pregnancy physical inactivity: Results from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Matern. Child Health J. 2010, 14, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfinder, M.; Feldmann, R.; Liebig, S. Alcohol during pregnancy from 1985 to 2005: Prevalence and high risk profile. Sucht 2013, 59, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfinder, M.; Kunst, A.E.; Feldmann, R.; van Eijsden, M.; Vrijkotte, T.G.M. Educational differences in continuing or restarting drinking in early and late pregnancy: Role of psychological and physical problems. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2014, 75, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, C.; Hutchinson, D.; Burns, L.; Wilson, J.; Elliott, E.; Allsop, S.; Najman, J.; Jacobs, S.; Rossen, L.; Olsson, C.; et al. Prenatal alcohol consumption between conception and recognition of pregnancy. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmulewitz, D.; Hasin, D.S. Risk factors for alcohol use among pregnant women, ages 15-44, in the United States, 2002 to 2017. Prev. Med. 2019, 124, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braspenningx, S.; Haagdorens, M.; Blaumeiser, B.; Jacquemyn, Y.; Mortier, G. Preconceptional care: A systematic review of the current situation and recommendations for the future. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2013, 5, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chronopoulou, E.; Seifalian, A.; Stephenson, J.; Serhal, P.; Saab, W.; Seshadri, S. Preconceptual care for couples seeking fertility treatment, an evidence-based approach. FS Rev. 2021, 2, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.; Kai, J.; Qureshi, N. The effects of preconception interventions on improving reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes in primary care: A systematic review. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 22, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawe, J.; Delbaere, I.; Ekstrand, M.; Hegaard, H.K.; Larsson, M.; Mastroiacovo, P.; Stern, J.; Steegers, E.; Stephenson, J.; Tydén, T. Preconception care policy, guidelines, recommendations and services across six European countries: Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2015, 20, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goossens, J.; Beeckman, D.; van Hecke, A.; Delbaere, I.; Verhaeghe, S. Preconception lifestyle changes in women with planned pregnancies. Midwifery 2018, 56, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Jain, K.; Behera, J.; Mishra, S.K.; Mehra, S. Community based reproductive health interventions for young married couples in resource-constrained settings: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, E.; Haber, J.; Krainovich-Miller, B.; Bella, A.; Vasilyeva, A.; Lange Kessler, J. Oral health in pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamos, C.A.; Thompson, E.L.; Avendano, M.; Daley, E.M.; Quinonez, R.B.; Boggess, K. Oral health promotion interventions during pregnancy: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2015, 43, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bombana, M.; Wensing, M.; Wittenborn, L.; Ullrich, C. Health Education about Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors in Gynecological and Obstetric Care: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Providers’ Views in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811674

Bombana M, Wensing M, Wittenborn L, Ullrich C. Health Education about Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors in Gynecological and Obstetric Care: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Providers’ Views in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811674

Chicago/Turabian StyleBombana, Manuela, Michel Wensing, Lisa Wittenborn, and Charlotte Ullrich. 2022. "Health Education about Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors in Gynecological and Obstetric Care: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Providers’ Views in Germany" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811674