Former Incarceration, Time Served, and Perceived Oral Health among African American Women and Men

Abstract

:1. Background and Theory

1.1. Mass Incarceration and Health Disparities

1.2. Incarcerated Populations and Oral Health

1.3. Predictors of Post-Release Oral Health

2. Summary and Hypotheses

2.1. Data and Methods

2.1.1. Data

2.1.2. Dependent Variable

2.1.3. Independent Variables

2.1.4. Covariates

2.1.5. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

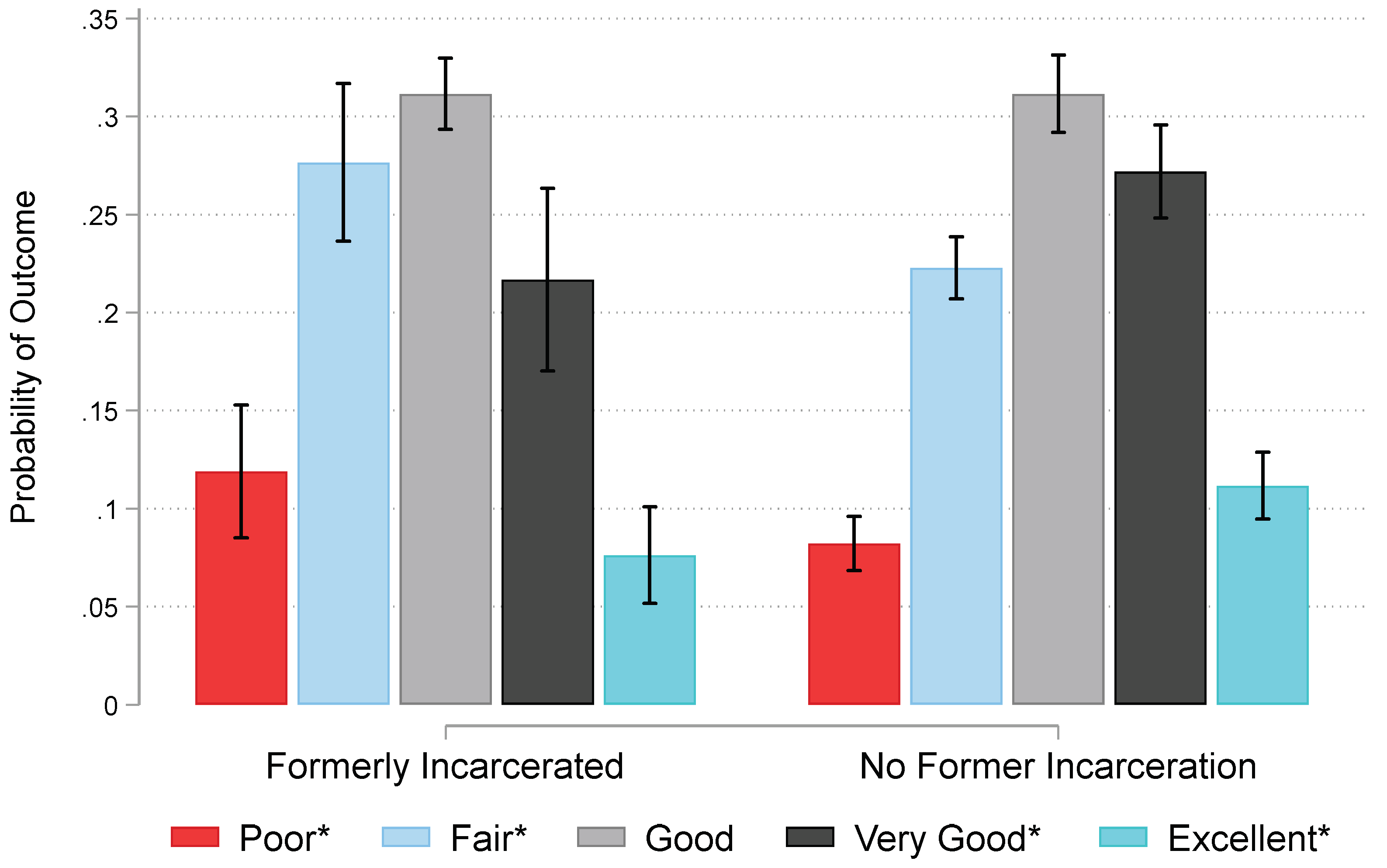

3.2. Incarceration, Duration, and Dental Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carson, E.A. Prisoners in 2020—Statistical Tables; NCJ 302776; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–50.

- Fair, H.; Walmsley, R. World Prison Population List; Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Wildeman, C. Assessing Mass Incarceration’s Effects on Families. Science 2021, 374, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, D. (Ed.) Mass Imprisonment: Social Causes and Consequences; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman, C.; Lee, H. Women’s Health in the Era of Mass Incarceration. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeman, C.; Wang, E.A. Mass Incarceration, Public Health, and Widening Inequality in the USA. Lancet 2017, 389, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoglia, M. Incarceration as Exposure: The Prison, Infectious Disease, and Other Stress-Related Illnesses. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2008, 49, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, L.B.; Wang, E.A. Health Care for People Who Are Incarcerated. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, J.; Talbert, R.D.; Woods, B.; Langford, A.; Cole, H.; Barcelona, V.; Crusto, C.; Taylor, J.Y. Police Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms in African American Women: The Intergenerational Impact of Genetic and Psychological Factors on Blood Pressure Study. Health Equity 2022, 6, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbert, R.D. Lethal Police Encounters and Cardiovascular Health among Black Americans. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie-Mizell, C.A.; Talbert, R.D.; Frazier, C.G.; Rainock, M.R.; Jurinsky, J. Race-Gender Variation in the Relationship between Arrest History and Poor Health from Adolescence to Adulthood. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2022, 114, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.J. Incarcerating Death: Mortality in U.S. State Correctional Facilities, 1985–1998. Demography 2010, 47, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camplain, R.; Lininger, M.R.; Baldwin, J.A.; Trotter, R.T. Cardiovascular Risk Factors among Individuals Incarcerated in an Arizona County Jail. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (IOM). Advancing Oral Health in America; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberger, J.A.; Strickhouser, S.M. Missing Teeth: Reviewing the Sociology of Oral Health and Healthcare. Sociol. Compass 2014, 8, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Disparities in Oral Health; Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- US 97; Estelle v. Gamble. Supreme Court of the United States: Washington, DC, USA, 1976; Volume 429, p. 103.

- Zaitzow, B.H.; Willis, A.K. Behind the Wall of Indifference: Prisoner Voices about the Realities of Prison Health Care. Laws 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isailă, O.-M.; Hostiuc, S. Malpractice Claims and Ethical Issues in Prison Health Care Related to Consent and Confidentiality. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, V.; Brondani, M.; von Bergmann, H.; Grossman, S.; Donnelly, L. Dental Service and Resource Needs during COVID-19 among Underserved Populations. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2022, 7, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosendiak, A.; Stanikowski, P.; Domagała, D.; Gustaw, W.; Bronkowska, M. Dietary Habits, Diet Quality, Nutrition Knowledge, and Associations with Physical Activity in Polish Prisoners: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northridge, M.E.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, R. Disparities in Access to Oral Health Care. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pękala-Wojciechowska, A.; Kacprzak, A.; Pękala, K.; Chomczyńska, M.; Chomczyński, P.; Marczak, M.; Kozłowski, R.; Timler, D.; Lipert, A.; Ogonowska, A.; et al. Mental and Physical Health Problems as Conditions of Ex-Prisoner Re-Entry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, K.; Stockard, J.; Ramberg, Z. The Impact of Socioeconomic Status and Race-Ethnicity on Dental Health. Sociol. Perspect. 2007, 50, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patterson, E.J.; Wildeman, C. Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course Revisited: Cumulative Years Spent Imprisoned and Marked for Working-Age Black and White Men. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 53, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, E.; Cook, D. The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 2021, 4, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittker, J.; John, A. Enduring Stigma: The Long-Term Effects of Incarceration on Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, E.J.; Talbert, R.D.; Brown, T.N. Familial Incarceration, Social Role Combinations, and Mental Health among African American Women. J. Marriage Fam. 2021, 83, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.N.; Bell, M.L.; Patterson, E.J. Imprisoned by Empathy: Familial Incarceration and Psychological Distress among African American Men in the National Survey of American Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2016, 57, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotter, R.T.; Lininger, M.R.; Camplain, R.; Fofanov, V.Y.; Camplain, C.; Baldwin, J.A. A Survey of Health Disparities, Social Determinants of Health, and Converging Morbidities in a County Jail: A Cultural-Ecological Assessment of Health Conditions in Jail Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Testa, A.; Fahmy, C. Oral Health Status and Oral Health Care Use among Formerly Incarcerated People. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R.; Richards, D. Factors Associated with Accessing Prison Dental Services in Scotland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogalska, A.; Barański, K.; Rachwaniec-Szczecińska, Ż.; Holecki, T.; Bąk-Sosnowska, M. Assessment of Satisfaction with Health Services among Prisoners—Descriptive Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douds, A.S.; Ahlin, E.M.; Kavanaugh, P.R.; Olaghere, A. Decayed Prospects: A Qualitative Study of Prison Dental Care and Its Impact on Former Prisoners. Crim. Justice Rev. 2016, 41, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter II, R.T.; Camplain, R.; Eaves, E.R.; Fofanov, V.Y.; Dmitrieva, N.O.; Hepp, C.M.; Warren, M.; Barrios, B.A.; Pagel, N.; Mayer, A.; et al. Health Disparities and Converging Epidemics in Jail Populations: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolcato, M.; Fiore, V.; Casella, F.; Babudieri, S.; Lucania, L.; Di Mizio, G. Health in Prison: Does Penitentiary Medicine in Italy Still Exist? Healthcare 2021, 9, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan, M.; Gonzalez, G.; Strong, J.D.; Augustine, D.; Chesnut, K.; Reiter, K.; Pifer, N.A. Triaged Out of Care: How Carceral Logics Complicate a ‘Course of Care’ in Solitary Confinement. Healthcare 2022, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayakar, M.M.; Shivprasad, D.; Pai, P.G. Assessment of Periodontal Health Status among Prison Inmates: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A.L.; Rodrigues, I.S.A.; De Melo Silveira, I.T.; De Oliveira, T.B.S.; De Almeida Pinto, M.S.; Xavier, A.F.C.; De Castro, R.D.; Padilha, W.W.N. Dental Caries Experience and Use of Dental Services among Brazilian Prisoners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moraes, L.R.; Duarte de Aquino, L.C.; Cruz, D.T.D.; Leite, I.C.G. Self-Perceived Impact of Oral Health on the Quality of Life of Women Deprived of Their Liberty. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, e5520652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mixson, J.M.; Eplee, H.C.; Fell, P.H.; Jones, J.J.; Rico, M. Oral Health Status of a Federal Prison Population. J. Public Health Dent. 1990, 50, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, D.S. Women’s Perceptions of Health Care in Prison. Health Care Women Int. 2000, 21, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, W.K.; Allison, M.K.; Fradley, M.F.; Zielinski, M.J. ‘You’Re Setting a Lot of People up for Failure’: What Formerly Incarcerated Women Would Tell Healthcare Decision Makers. Health Justice 2022, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, D.L.; Reisine, S. Barriers to Dental Care for Older Minority Adults: Barriers to Dental Care. Spec. Care Dentist. 2015, 35, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujicic, M.; Buchmueller, T.; Klein, R. Dental Care Presents The Highest Level Of Financial Barriers, Compared To Other Types Of Health Care Services. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 2176–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davenport, C.; Elley, K.; Salas, C.; Taylor-Weetman, C.L.; Fry-Smith, A.; Bryan, S.; Taylor, R. The Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Routine Dental Checks: A Systematic Review and Economic Evaluation. Health Technol. Assess 2003, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treadwell, H.M.; Formicola, A.J. Improving the Oral Health of Prisoners to Improve Overall Health and Well-Being. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98 (Suppl. 1), S171–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J.W.; Wang, E.A.; Nunez-Smith, M.; Lee, H.; Comfort, M. Discrimination Based on Criminal Record and Healthcare Utilization among Men Recently Released from Prison: A Descriptive Study. Health Justice 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heeringa, S.G.; Wagner, J.; Torres, M.; Duan, N.; Adams, T.; Berglund, P. Sample Designs and Sampling Methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 13, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.S.; Torres, M.; Caldwell, C.H.; Neighbors, H.W.; Nesse, R.M.; Taylor, R.J.; Trierweiler, S.J.; Williams, D.R. The National Survey of American Life: A Study of Racial, Ethnic and Cultural Influences on Mental Disorders and Mental Health. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 13, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muruthi, J.R.; Muruthi, B.A.; Thompson Cañas, R.E.; Romero, L.; Taiwo, A.; Ehlinger, P.P. Daily Discrimination, Church Support, Personal Mastery, and Psychological Distress in Black People in the United States. Ethn. Health 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, A.L. Ethnicity, Nativity, and the Effects of Stereotypes on Cardiovascular Health among People of African Ancestry in the United States: Internal versus External Sources of Racism. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 1010–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.C.; Nicholson, H.L. Perceived Discrimination and Mental Health among African American and Caribbean Black Adolescents: Ethnic Differences in Processes and Effects. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irby-Shasanmi, A.; Erving, C.L. Do Discrimination and Negative Interactions with Family Explain the Relationship between Interracial Relationship Status and Mental Disorder? Socius 2022, 8, 23780231221124852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulos, G.S.; Cisneros, A.; Sanchez, M.; Lunos, S.; Wolff, L.F. Validity of Self-Reported Periodontal Measures, Demographic Characteristics, and Systemic Medical Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozier, Y.C.; Heaton, B.; Bethea, T.N.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Garcia, R.I.; Rosenberg, L. Predictors of Self-Reported Oral Health in the Black Women’s Health Study. J. Public Health Dent. 2020, 80, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Mejia, G.C.; Broadbent, J.M.; Poulton, R. Construct Validity of Locker’s Global Oral Health Item. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaton, B.; Gordon, N.B.; Garcia, R.I.; Rosenberg, L.; Rich, S.; Fox, M.P.; Cozier, Y.C. A Clinical Validation of Self-Reported Periodontitis Among Participants in the Black Women’s Health Study. J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshipura, K.J.; Pitiphat, W.; Douglass, C.W. Validation of Self-Reported Periodontal Measures Among Health Professionals. J. Public Health Dent. 2002, 62, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitiphat, W.; Garcia, R.I.; Douglass, C.W.; Joshipura, K.J. Validation of Self-Reported Oral Health Measures. J. Public Health Dent. 2002, 62, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldossri, M.; Saarela, O.; Rosella, L.; Quiñonez, C. Suboptimal Oral Health and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the Presence of Competing Death: A Data Linkage Analysis. Can. J. Public Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Socioeconomic Status and Self-Rated Oral Health; Diminished Return among Hispanic Whites. Dent. J. 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, M.T.; Taylor, R.J.; George, J.R.; Schlaudt, V.A.; Ifatunji, M.A.; Chatters, L.M. Correlates of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms among Black Caribbean Americans. Int. J. Ment. Health 2021, 50, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.T.; Taylor, R.J.; Himle, J.A.; Chatters, L.M. Demographic and Health-Related Correlates of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms among African Americans. J. Obs. -Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2017, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.D.; Fang, X.; Luo, F. The Impact of Parental Incarceration on the Physical and Mental Health of Young Adults. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1188–e1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wildeman, C.; Schnittker, J.; Turney, K. Despair by Association? The Mental Health of Mothers with Children by Recently Incarcerated Fathers. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 216–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Using the Margins Command to Estimate and Interpret Adjusted Predictions and Marginal Effects. Stata J. 2012, 12, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rantanen, T.; Järveläinen, E.; Leppälahti, T. Prisoners as Users of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services: A Finnish Attitude Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| African American Women | African American Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean/% | SD | Mean/% | SD |

| Oral Health Status | ||||

| Self-rated oral health * (range 1–5, 5 = excellent) | 3.08 | (1.21) | 3.18 | (0.98) |

| Incarceration Experience | ||||

| Formerly incarcerated * | 6.33% | — | 21.05% | — |

| Years spent incarcerated * a (range 0–30.34) | 1.81 | (3.50) | 2.35 | (4.11) |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age (in years; range 18–93) | 42.64 | (17.52) | 41.58 | (14.12) |

| Education (in years; range 4–17) | 12.48 | (2.59) | 12.50 | (2.21) |

| Employed (yes = 1) * | 63.68% | — | 72.67% | — |

| No insurance (yes = 1) | 20.02% | — | 23.01% | — |

| Federal program insurance * (yes = 1) | 26.20% | — | 15.18% | — |

| Employee sponsored insurance * (yes = 1) | 52.78% | — | 61.81% | — |

| Married/cohabiting (yes = 1) * | 35.88% | — | 50.30% | — |

| Formerly married * (yes = 1) | 32.25 % | — | 19.14% | — |

| Never married (yes = 1) | 31.86% | — | 30.56% | — |

| Sample size | 2144 | 1166 | ||

| Self-Rated Oral Health (Range 1–5, 5 = Excellent) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American Women | African American Men | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| Variables | OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE |

| Incarceration Experience | ||||||||

| Formerly incarcerated (yes = 1) | 0.65 ** | (0.10) | — | — | 0.74 * | (0.09) | — | — |

| Years spent Incarcerated | — | — | 0.93 | (0.09) | — | — | 1.16 ** | (0.06) |

| Years spent Incarcerated | — | — | 1.00 | (0.00) | — | — | 0.99 * | (0.00) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age (in years) | 0.98 *** | (0.01) | 0.94 * | (0.02) | 0.98 *** | (0.01) | 0.98 | (0.01) |

| Education (in years) | 1.09 *** | (0.02) | 1.12 * | (0.02) | 1.09 ** | (0.04) | 1.21 * | (0.10) |

| Employed (yes = 1) | 1.01 | (0.14) | 0.93 | (0.57) | 1.53 * | (0.25) | 2.28 * | (0.85) |

| Federal program Insurance (ref = no insurance) | 0.79 | (0.10) | 0.83 | (0.51) | 0.97 | (0.18) | 1.22 | (0.45) |

| Employee sponsored insurance (ref = no insurance) | 1.32 * | (0.14) | 1.43 | (0.74) | 1.05 | (0.17) | 1.28 | (0.44) |

| Formerly married (ref = married/cohabiting) | 0.81 * | (0.08) | 1.13 | (0.52) | 0.78 | (0.12) | 0.52 * | (0.17) |

| Never married (ref = married/cohabiting) | 1.13 | (0.12) | 1.59 | (0.57) | 1.13 | (0.16) | 1.46 | (0.42) |

| Sample size | 2144 | 127 | 1166 | 252 | ||||

| BIC | 4396.310 | 318.592 | 3333.870 | 773.058 | ||||

| McFadden Pseudo R2 | 0.031 | 0.080 | 0.031 | 0.060 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Talbert, R.D.; Macy, E.D. Former Incarceration, Time Served, and Perceived Oral Health among African American Women and Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12906. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912906

Talbert RD, Macy ED. Former Incarceration, Time Served, and Perceived Oral Health among African American Women and Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12906. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912906

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalbert, Ryan D., and Emma D. Macy. 2022. "Former Incarceration, Time Served, and Perceived Oral Health among African American Women and Men" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12906. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912906

APA StyleTalbert, R. D., & Macy, E. D. (2022). Former Incarceration, Time Served, and Perceived Oral Health among African American Women and Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12906. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912906