1. Loneliness in Intimate Relationships Scale (LIRS): Development and Validation

Establishing and maintaining close intimate relationships with a significant other has been recognized as a fundamental human motivation [

1,

2]. Similarly, marriage is perceived as the most intimate officially sanctioned adult bonding, serving as a primary source of affection, love, support [

3,

4] and physical and emotional well-being [

5].

In the US, approximately sixty percent of adults (60% of males and 57% of females) aged 18 and over are married, while overall, 72% have experienced marriage and may thus be married, divorced, or widowed. Marriage, or a long-term intimate commitment, is central in Western culture, and although they presently have smaller chances of succeeding, they are still, by and large, the preferred lifestyles adult [

4]. Strong [

4] suggested that intimate relationships buffer against loneliness, positively affect our self-esteem, and are shown to be related to happiness, contentment, and a sense of well-being [

6]. In close relationships, intimacy has been rated as more important for relationship satisfaction than autonomy, individuality, freedom, agreement, or sexual satisfaction [

7].

This, however, does not prevent the married from experiencing loneliness. For example, Tornstam [

8] found that 40% of married people in Sweden experienced more loneliness than unmarried people. It may intuitively seem paradoxical that a person can be both married and lonely. However, when marriages lose their vitality, spouses become prone to loneliness [

9]. There is a tendency to believe that marriage and intimate relations tend to fend off loneliness because a companion is always around. However, Barbour [

10] found that 20% of wives and 24% of husbands are significantly lonely, and as loneliness increases in the marriage or intimate relationship, so does depression.

Loneliness in marriage may be especially distressing because it is inconsistent with expectations about marriage and may have a significant effect on one’s physical, emotional and spiritual well-being [

11,

12]. As indicated by Fincham and Rogge [

13], there are two approaches that examine the construct of relationship quality. One focuses on the relationship, or the interpersonal exchange between the couple, namely their interaction, the manner in which they resolve conflicts, and their communication patterns. The other, the intrapersonal approach, which the present study took, focuses on subjective judgments of each partner and her or his evaluation of the marriage or intimate relationship.

Helping couples deal with conflicts, problematic issues, or dissatisfaction is what marital and couple therapists commonly do. However, in order to be effective, therapy needs to be clear as to what to focus on and address the specific aspects of the relationship that need the therapist’s help and attention. There are a variety of assessment tools geared to examine couple relationships and problematic issues, including the Locke–Wallace Marital Adjustment Scale [

14] the Quality of Relationship Inventory [

15], the Brief Romantic Relationship Interaction Coding Scheme [

16], the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale [

17], and the Retired Spousal Intrusion Scale [

18]. However, although important, valid and reliable instruments have been developed for assessing different aspects of relationships, none address the issue of loneliness, which can be highly disruptive and damaging to an intimate relation.

We, therefore, developed a new scale, the Loneliness in Intimate Relationships Scale [LIRS], which aims to fulfill this need. It is expected that there may be a moderate association between the present general loneliness scales and the one described herein since the one that we developed addresses relational issues that were not addressed in the existing loneliness questionnaires. The present manuscript does not check this assumption, and that will be addressed by our planned future research project. The present paper describes research aimed at developing a new scale for assessing loneliness in relationships for adults and testing its basic psychometric properties regarding reliability and validity. The development of the Loneliness in Intimate Relationships Scale followed the standard principles of a non-reactive methodology for questionnaire construction described in the

Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (APA, 2014). Such methodology ensures that the scale covers all aspects of the construct and meets the highest validity and reliability criteria.

Table 1 presents the stages in the development of the Loneliness in Intimate Relationships Scale.

6. Conclusions

Various pitfalls, stumbling blocks, and hazards, such as hurt feelings, ostracism, jealousy, lying, and betrayal, may harm emotional relations and feelings of love [

39]. We want and need to be loved by our intimate partners and hope that our relational value—the degree to which our partner considers our intimate relationship valuable, important, and close—is as high as we perceive it to be. It is painful to discover that our partner may perceive it as lower than we would like it to be perceived. A dissonance is thus created between what we envision it to be and what our partner apparently sees in it. Should relational devaluation occur, and we are no longer thought of as positively as before, we experience pain, anger, hurt, and loneliness [

40,

41] described ideal romantic love as a situation where the one I love loves me back since “Out of all the people she could love, she chooses to love me. That suggests that the reason why she loves me should be to do with the things that set me apart from others” (p. 163). When those feelings seem to change, when one stops feeling so valued and special to their partner, it may lead to their feeling neglected, unappreciated, and thus lonely. When one is not as important to one’s lover as one knows one was in the past, it ushers in loneliness, sadness, and longing to recreate what was, what made one feel so good and special in the first place.

The newly created scale is expected to be valuable, not only for researchers in the areas of loneliness and marital relationships but for clinicians as well, who would be able to identify specific shortcomings in the relationships which contribute to loneliness and thus be able to more specifically address them.

7. Limitations

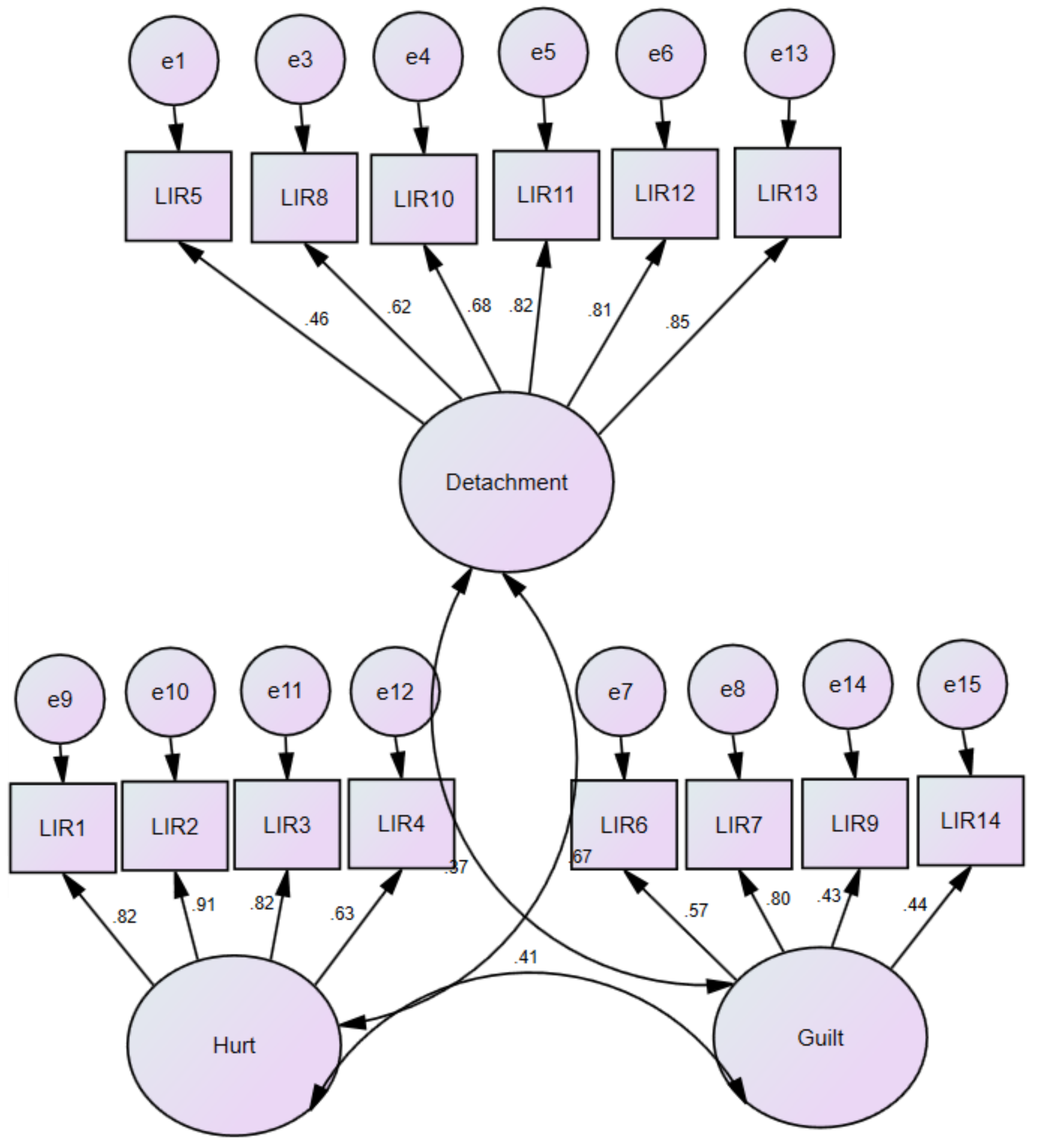

There are several scales in use for assessing relationships, couple’s satisfaction, and loneliness. However, none addresses the specific issue of loneliness that may exist in intimate relations, which needs to be identified and measured. The present study was designed to integrate theoretical frameworks of loneliness in intimate relationships with empirical data, resulting in the development of a new scale, the Loneliness in Intimate Relationships Scale (LIRS). The preliminary versions of the LIRS were based on semi-structured questionnaires administered to a large heterogenic Israeli sample and on analyses of existing relevant scales. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses resulted in a well-structured 14-item scale depicting emotional, behavioral, and cognitive reactions and coping with loneliness in intimate relationships. The analyses revealed that the experience of loneliness in intimate relationships encompasses three main aspects: detachment, hurt, and guilt. Rokach and Brock [

12] developed a scale to explore the qualitative aspects of loneliness in general. Their five-dimensional model included those very same factors: the hurt, which is a salient ingredient of loneliness, the hurt that follows feeling alone and unwanted, and the detachment that some people resort to in order to prevent further rejections, hurt, and pain. The LIRS evidenced excellent reliability levels with internal consistency estimates in the 90s. Furthermore, construct validity tests showed that, as expected, the LIRS subscales are positively related to higher levels of reported general and social loneliness and greater interpersonal needs and depression and are more prevalent among individuals who experienced loneliness in a relationship on a continuous, not state-related, basis.

Being connected is one of the most important human needs. It is so important that it affects not only emotional and physical well-being but is directly related to mortality rates. Studies have demonstrated a steep rise in mortality rates among socially isolated individuals [

42]. However, being lonely does not necessarily reflect being unconnected with other human beings. The empirical and clinical literature conceptualizes loneliness as a two-dimensional construct, discriminating between objective loneliness, which reflects the quantity of one’s social interactions, and subjective loneliness, which concerns the quality of those interactions and reflects dissatisfaction with one’s social relationships, or as described by Weiss [

43], as a “gnawing, chronic disease without redeeming features” (in [

44], p. 446). Nevertheless, these two aspects of loneliness are not necessarily associated. According to Gottman’s [

44,

45] Distance and Isolation Cascade model, deterioration of marital distress can eventually result in disengagement, isolation, and loneliness. Gottman depicts the process leading from emotional flooding within a relationship to the feeling that any attempt to discuss problems will be pointless and futile—an approach that will eventually lead to emotionally parallel lives. When a couple reaches this advanced stage of relational deterioration, there is a complete absence of expressions of love and affection, and the partners experience emotional isolation, disengagement, and loneliness. Partners then find themselves emotionally uninvolved with and unavailable to each other. This “empty shell” marriage, which is characterized by partners’ disengagement and indifference, is a common antecedent of loneliness [

46].

Marriage, similarly to any long-term intimate relationship, is an appropriate state for analyzing emotional loneliness separately from objective social isolation. The fact that loneliness in intimate relationships revealed itself not as a unitary concept but as being comprised of three stable and valid facets, namely, detachment, hurt, and guilt, may have important clinical implications, especially given the lack of couple-based therapy techniques designed specifically for the treatment of loneliness in close relationships [

47]. As our studies revealed, detachment is a major factor of romantic loneliness, and it is thus reasonable to suggest that therapeutic interventions aimed at the improvement of attachment bonding and intimacy may potentially alleviate loneliness. More specifically, interventions that strengthen intimacy, emotional security, and mutual support are likely to encourage couples in therapy to reengage emotionally, thus reducing loneliness. Additionally, focusing on strengthening attachment bonding in romantic relationships is a preventive measure against relational loneliness. By employing preventive measures, educators and practitioners can utilize ways to help couples protect themselves from emotional detachment as a protective shield from romantic loneliness.

The authors note several limitations of these studies. First, the LIRS was not validated against behavioral measures. It is unclear how self-ratings on the LIRS manifest themselves behaviorally, thus limiting the scale’s ecological validity as a predictive tool for change. Future research should test the clinical utility of the LIRS to assess the level and type of relationship loneliness. Secondly, the LIRS was not examined in comparison to existing, general loneliness scales. While it is expected that the correlation would possibly be a moderate one, future research could examine it more closely. Thirdly, the interrelations between the three main subscales of the LIRS were not thoroughly examined. Different patterns of loneliness resulting from different combinations of levels of detachment, hurt, and guilt may manifest themselves in similar or different patterns of reactions to the stressful situation, thus calling for different types of psychological interventions. Finally, the LIRS was developed and validated with Israeli participants. This may, at present, limit the generalization of the application of this scale to other cultures. Future studies are needed in order to test the generalizability of the measurement model by testing it with other native English-speaking populations.