Determinants of Food Waste from Household Food Consumption: A Case Study from Field Survey in Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives, Definitions, and Methodology

2.1. Objectives for Reducing FLW

- (1)

- Food security is the main objective for many societies. According to the United Nations’ Committee on World Food Security, food security defines a situation in which all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life. FLW reduction or prevention can potentially help to move up food security, in particular in developing countries where food security is often crucial. Nonetheless, donations to food banks can also contribute to the reduction of FLW and improve the food security of endangered groups.

- (2)

- (3)

- Environmental protection or economic sustainability is another important objective. Economic sustainability refers to practices for long-term economic growth without having negative impacts on social, environmental, or cultural levels. FLW often has negative effects on the environment, e.g., through landfills. The economic costs of landfills are mostly not incorporated in the cost of production or waste.

- (4)

- For many people, FLW also has a moral dimension. FLW is considered to be unethical. A lack of appreciation of discarded food is contemplated to be morally unacceptable by many people. For instance, wasted meat is disrespectful of the animal lives taken. Many cultures honour respectful and FLW-minimising handling of foods [1,19].

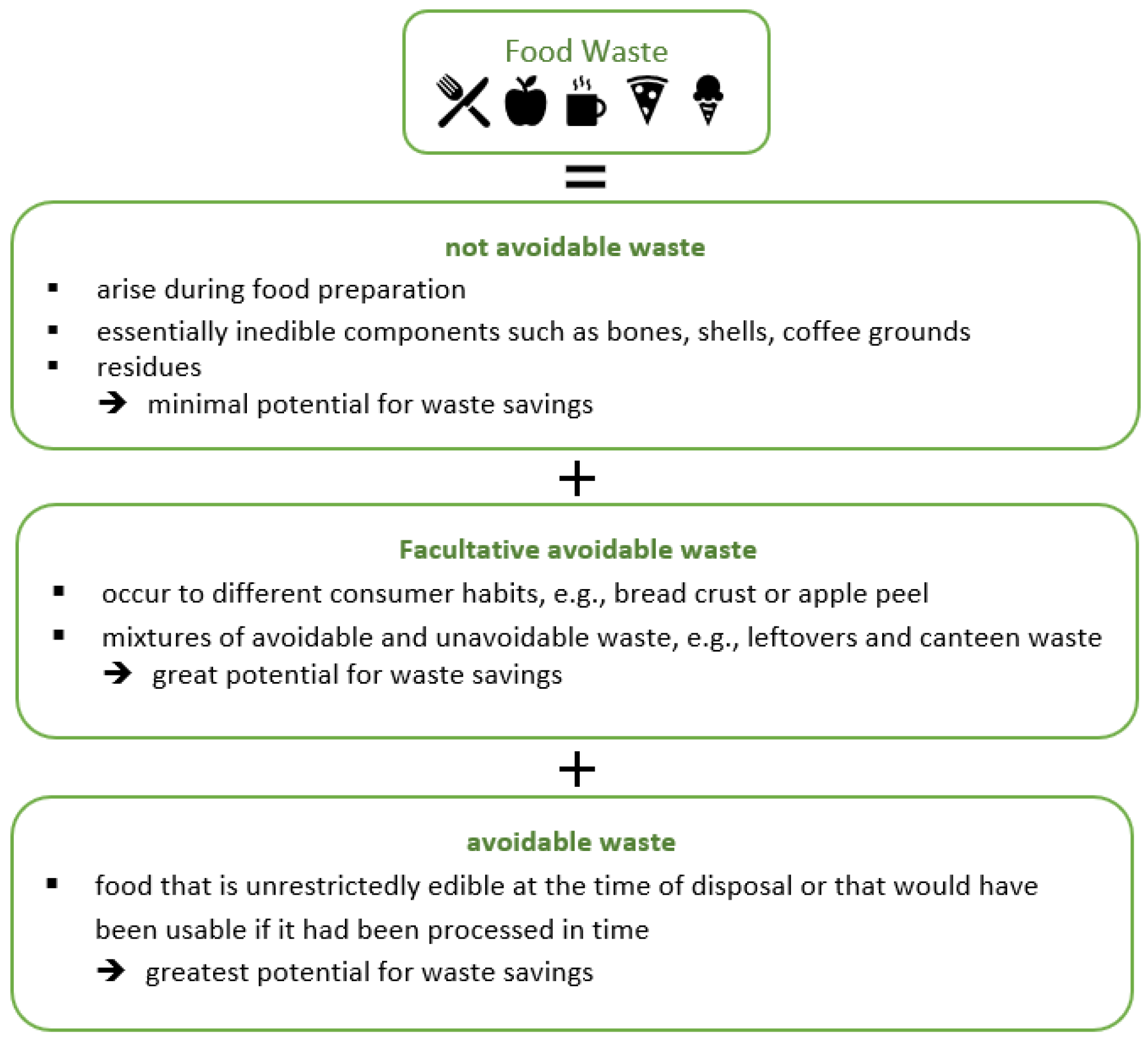

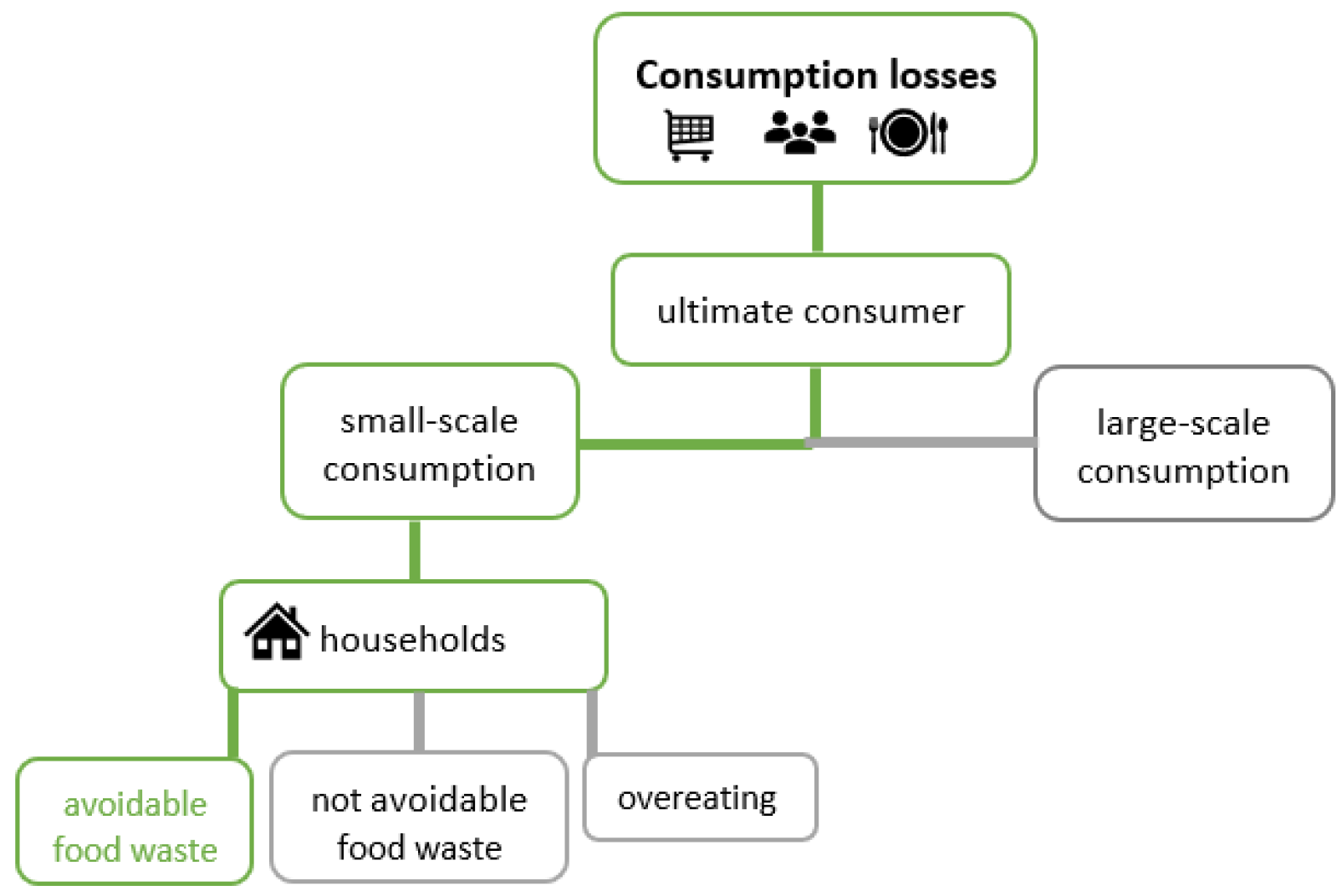

2.2. Definition of FLW

2.3. Measuring and Aggregating FLW

2.4. Approaches to Estimate FLW

- (1)

- (2)

- Waste composition analyses (WCA) focus on a sorting system for household waste. WCA are complex and expensive. Only FW disposed of via the municipal waste system is documented. The WCA have limits in identifying foods and their kinds [27]. The awareness of being part of an FW study may lead to behavioural changes (“Hawthorne effect”) [2,12].

- (3)

- In food waste diaries household members document the amount of FW during a certain period. FW diaries require the time and effort of participants. Results, however, may be comparatively more accurate than surveys. Households may still adjust their behaviour [30,31,32]. In contrast to WCA, FW diaries allow to analyse the waste composition and its determinants. Food fed to animals, disposed in the sewer, or composted is documented. Some household FW may even not be noted, e.g., food is taken to and wasted at the office or school [12]. Though often overrated, the share of unavoidable waste is estimated [13,33].

- (4)

- Meta-analyses are based on the results of other primary surveys or extrapolations. The main strength of this method is the access to large amounts of data, which could facilitate comparability.

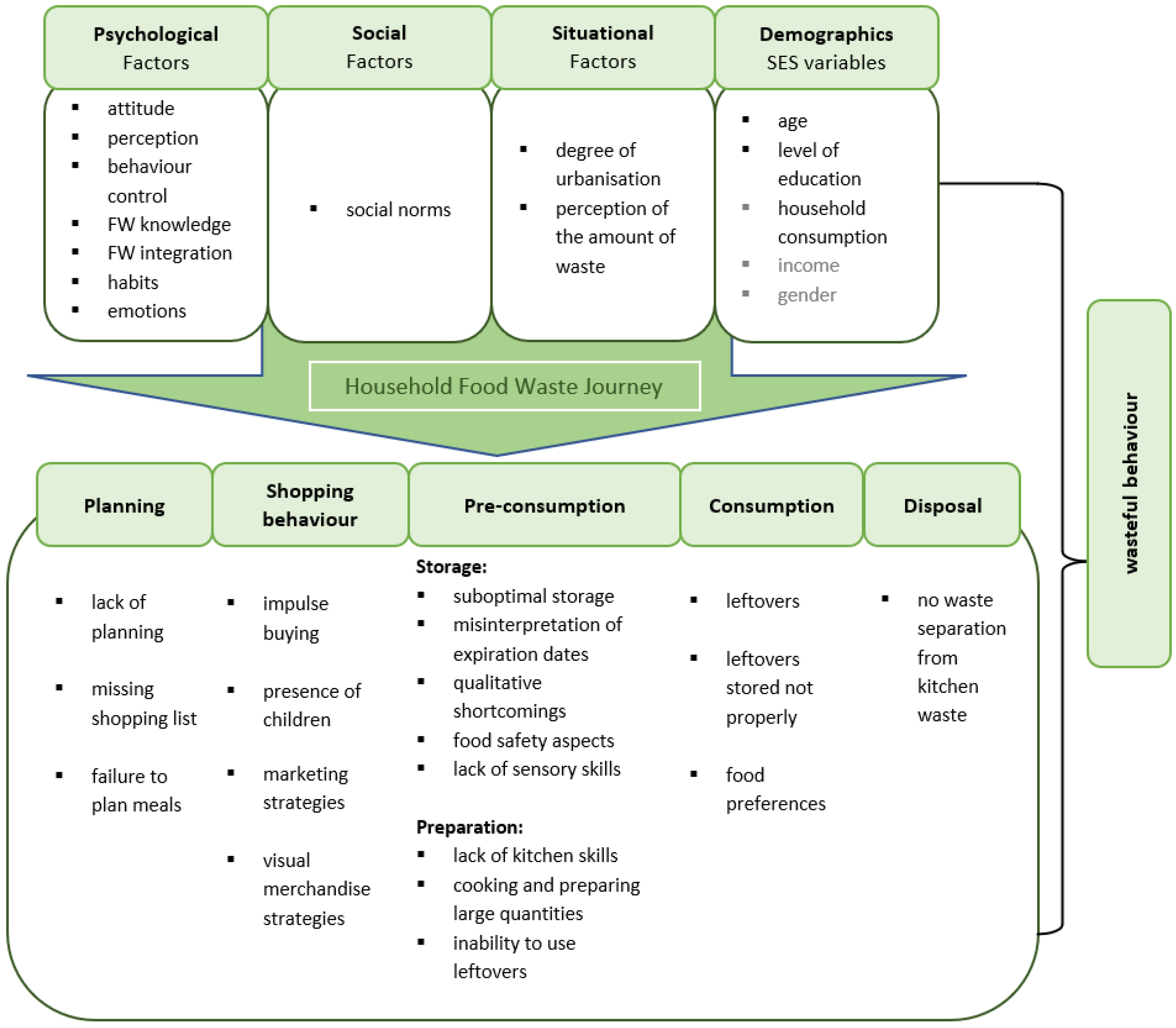

2.5. Causes of Consumer FW

2.6. A Benchmark Model of Household FW

3. Literature Review

| Country | Study | Method1 | Total FW /Capita and Year [kg] | Avoidable FW /Capita and Year [kg] | % | Avoidable FW/Capita and Year [€] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Environment Agency Austria, 2017 [42] | WCA | 39 | 19 | 12 | n.a. |

| Belgium | Flemish Food Supply Chain Platform for Food Loss, 2017 [43] | WCA | 72.3 | 32.7 | 45 | n.a. |

| Canada | Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019 [54] | WCA | 79 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Denmark | Danish Environmental Protection Agency, 2018 [44] | WCA | 80.7 | 44 | 24.8 | n.a. |

| Edjabou et al., 2016 [45] | WCA | 85 | 48 | 56.4 | n.a. | |

| Tonini, D., Brogaard, L.K.-S., & Astrup, T.F., 2017 [58] | WCA | n.a. | 46 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Estonia | Moora, Evelin et al., 2015 [47] | D + Q | 54 | 17 | 36 | 17.12 |

| Europe | Caldeira et al., 2019 [50] | M + S | 21–139 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Monier et al. (2010) [48] | M + S | 7–133 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Stenmarck et al., 2016 [49] | M + S | 91 | 71 | 60 | n.a. | |

| Finland | Silvennoinen et al., 2014 [59] | D | n.a. | 23 | n.a. | 70 |

| Katajajuuri et al., 2014 [39] | D + Q | 67 | 23 | 35.4 | 70 | |

| France | ADEME, 2016 [60] | S | 85 | 24 | 28 | n.a. |

| Germany | Cofresco, 2011 [61] | D + Q | 80 | 47.2 | 59 | 182.9 |

| Jörissen et al., 2015 [27] | Q | n.a. | 7.2 g | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Hafner et al., 2012 [5] | S | 81.6 | 38.4 | 47 | 94–122.2 | |

| Noleppa und Cartsburg, 2015 [19] | S | 63 | 32.94 | 54 | n.a. | |

| Schmidt et al., 2019 [12] | D + Q | 54.5 | 27.0 | 44 | 75 | |

| Greece | Abeliotis et al., 2015 [62] | D | 98.9 | 29.8 | 30,1 | n.a. |

| Hungary | Kasza et al., 2020 [63] | D + Q | 65.49 | 31.97 | 48.8 | n.a. |

| Italy | Giordano et al., 2019 [33] | D + Q | 67 | 27.6 | 41.2 | n.a. |

| Jörissen et al., 2015 [27] | Q | n.a. | 6.6 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Latvia | Tokareva, T., 2017 [64] | S | 55 | n.a. | 22.7 | 237.78 |

| Luxemburg | Luxembourg Environment Ministry, 2020 [46] | WCA | 88.5 | 23.5 | 40.5 | 75.5 |

| Netherlands | The Netherlands Nutrition Centre Foundation, 2019 [51] | WCA + Q | 50 | 34.3 | 68.6 | 120 |

| Van Dooren, C., 2019 [65] | WCA + S + M | 61.8 | 41.2 | 66.7 | n.a. | |

| Norway | Hanssen et al., 2016 [36] | WCA + Q | 79 | 46.3 | 58.6 | n.a. |

| Williams et al., 2012 [38] | D + Q | n.a. | 44.2 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Poland | Steinhoff-Wrześniewska, 2015 [53] | WCA | 50 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Portugal | Baptista, P., Campos, I., Pires, I., & Vaz, S., 2012 [28] | Q | 31 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Romania | Dumitru et al., 2020 [29] | Q | n.a. | 11.8 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Slovenia | Vidic, T., & Žitnik, M., 2017 [52] | Q + S | 73 | 27 | 36 | n.a. |

| Spain | Ministerio de Agricultura, 2018 [66] | D + S | 38.22 | 27 | 70 | n.a. |

| Sweden | Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 2014 [67] | WCA | 81 | 28 | 35 | n.a. |

| Switzerland | Beretta & Hellweg, 2019 [56] | WCA + S | n.a. | 91.8 | 45 | n.a. |

| United Kingdom | WRAP, 2020 [57] | WCA | 100 | 68.5 | 68.5 | 244.58 |

| USA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2020a [65] | M | 59 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

4. Data

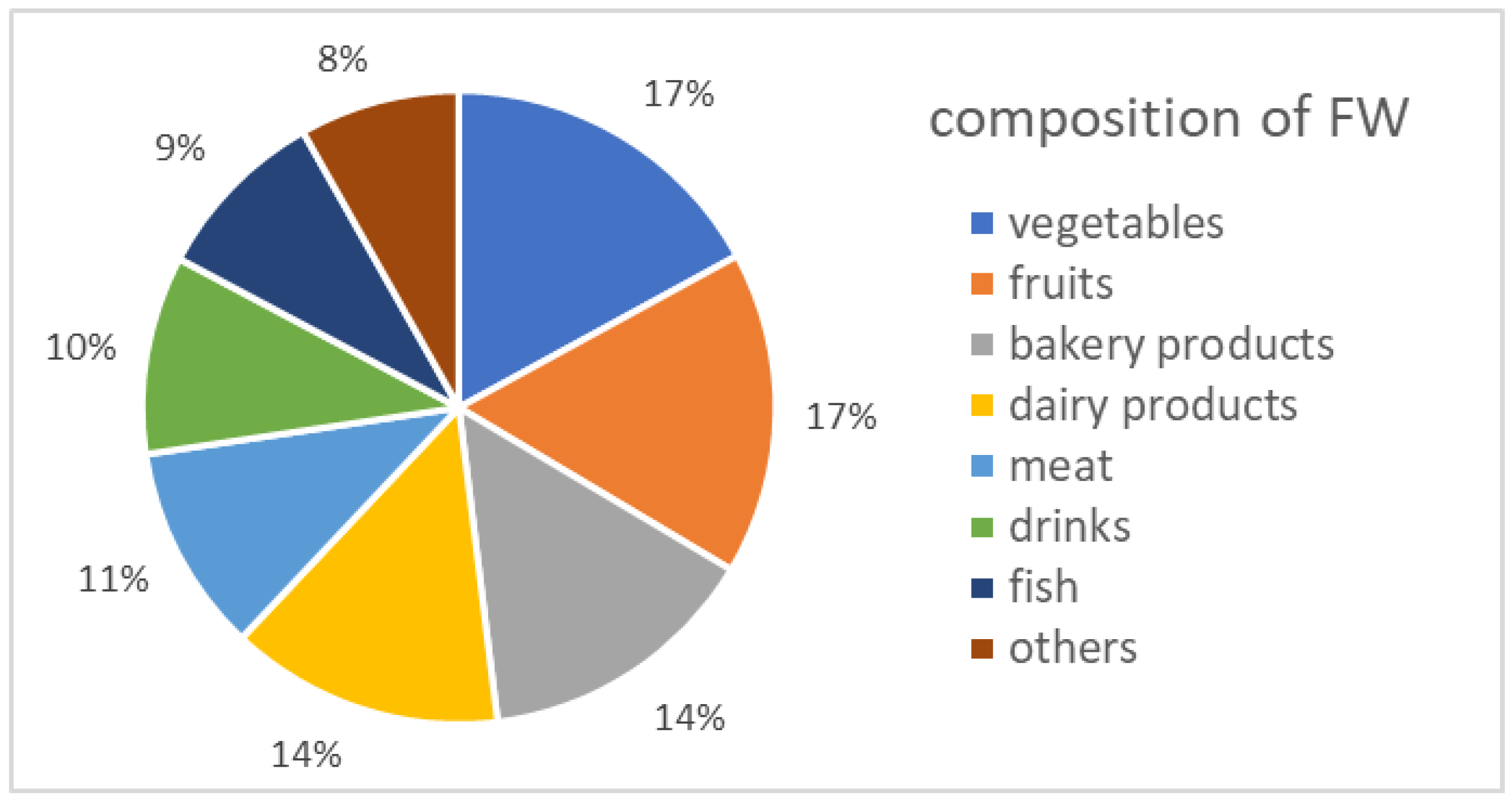

5. Results

6. Conclusions

7. Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Information-based measures include government-sponsored public information campaigns aimed to raise public awareness of FW and promote sustainable consumption. This includes labels, certifications, and guidelines to educate consumers about the consequences of FW. This should enable sovereign and conscious consumer decisions and influence consumer preferences toward resource-efficient food consumption [3,5,77]. Changing consumer behaviour through direct communication about the need to reduce FW is crucial [6,78]. Usually, consumers do not react to appeals but are rather guided by incentives [26]. Personal benefits of reducing the waste rate, such as financial savings or “doing what is morally right”, should therefore be communicated. If consumers understand that wasting food is wasting money, FW may be reduced. Nonetheless, the costs of reducing FW should be considered as well. Furthermore, the health risks of consuming food after the best-before date or any bad food need to be taken into consideration. People need to be better prepared for such decisions. In the long term, school courses on the issue should be installed. In addition to such instruments, there are so-called “nudging” instruments. These try to indirectly influence and steer the consumer [79]. An example is a government-funded cooking class to improve housekeeping skills [23,80]. The conscious handling of food and food management is critical to reducing waste [6,38]. In this regard, the government should start some initiatives using social networks.

- (2)

- Market-based and regulatory measures include subsidies and taxes on specific foods or food components [80]. General sustainability goals in the food sector such as reducing land use and limiting greenhouse gas emissions must be clearly defined for regulatory measures [77]. A higher tax on meat, a food that takes a lot of resources to produce, would be an example. Furthermore, rewards may be paid to consumers reducing their waste by reducing their garbage pick-up fees. Product labels could also inform about the resource use in production and handling to make consumer more aware of the consequences of not using or wasting the product.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention. In Proceedings of the Study Conducted for the International Congress Save Food, at Interpack 2011, Düsseldorf, Germany, 16–17 May 2011; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. ISBN 978-92-5-107205-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.; Schneider, F.; Leverenz, D.; Hafner, G. Food Waste in Germany—Baseline—2015; Thünen Institute: Braunschweig, Germany, 2015; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Koester, U.; Loy, J.-P.; Ren, Y. Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste—Reconsidered; Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies: Halle (Saale), Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C.; Denniss, R.; Baker, D. Wasteful Consumption in Australia; The Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2005; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, G.; Barabosz, J.; Schneider, F.; Lebersorger, S.; Scherhaufer, S.; Schuller, H.; Leverenz, D.; Kranert, M. Ermittlung der Weggeworfenen Lebensmittelmengen und Vorschläge zur Verminderung der Wegwerfrate bei Lebensmitteln in Deutschland; Institut für Siedlungswasserbau, Wassergüte- und Abfallwirtschaft: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE; Pinstrup-Andersen, P.; Rahmanian, M.; Allahoury, A.; Hendriks, S.; Hewitt, J.; Guillou, M.; Iwanaga, M.; Kalafatic, C.; Kliksberg, B. Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems; HLPE-FSN: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Çakir, M.; Peterson, H.H.; Novak, L.; Rudi, J. On the Measurement of Food Waste. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021. Available online: http://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- United Nations. Transformation Unserer Welt: Die Agenda 2030 Für Nachhaltige Entwicklung; 2015; Vol. A/RES/70/1*. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Delgado, L.; Schuster, M.; Torero, M. Reality of Food Losses: A New Measurement Methodology; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thünen Institute. Lebensmittelverschwendung Stärker ins Bewusstsein Rücken Internationaler Tag gegen Lebensmittelverschwendung am 29 September 2020; Thünen Institute: Braunschweig, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.G.; Schneider, F.; Leverenz, D. Lebensmittelabfälle in Deutschland—Baseline 2015; Thünen-Institut: Braunschweig, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thünen-Institut. Lebensmittelverschwendung Befeuert Klimawandel Neue Studie Bilanziert Treibhausgasemissionen der in Deutschland Konsumierten Lebensmittel und Zeigt Wege Auf, Lebensmittelabfälle zu Reduzieren; Thünen Institute: Braunschweig, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft. Klöckner: Reduzierung der Lebensmittelverschwendung ist ökonomische Herausforderung, Ökologische und Ethische Verpflichtung; Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food Waste within Food Supply Chains: Quantification and Potential for Change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Liu, G.; Parfitt, J.; Liu, X.; Herpen, E.V.; O’Connor, C.; Östergren, K.; Cheng, S. Missing Food, Missing Data? A Critical Review of Global Food Losses and Food Waste Data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6618–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Östergren, K.; Gustavsson, J.; Bos-Brouwers, H.; Timmermans, T.; Hansen, O.-J.; Møller, H.; Anderson, G.; O’Connor, C.; Soethoudt, H.; Quested, T.; et al. FUSIONS. Definitional Framework for Food Waste; FUSIONS: Göteborg, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koester, U. Food Loss and Waste as an Economic and Policy Problem. Front. Econ. Glob. 2017, 17, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noleppa, S.; Cartsburg, M. Nahrungsmittelverbrauch und Fußabdrücke des Konsums in Deutschland—Eine Neubewertung unserer Ressourcennutzung; WWF: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EG. Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Verordnung (EG) Nr. 178/2002 Des Euopäischen Parlaments und des Rates. 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32002R0178 (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Rural Poverty in Developing Countries and Means of Poverty Alleviation; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Grethe, H.; Dembélé, A.; Duman, N. How to Feed the World’s Growing Billions: Understanding FAO World Projections and Their Implications; Heinrich Böll Stift: Berlin, Germany; WWF: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Principato, L. Food Waste at Consumer Level; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-78886-9. [Google Scholar]

- ISuN—Institut für Nachhaltige Ernährung und Ernährungswirtschaft. Verringerung von Lebensmittelabfällen—Identifikation von Ursachen und Handlungsoptionen in Nordrhein- Westfalen; Münster University of Applied Sciences: Münster, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BCFN—Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition Food Waste. Causes, Impacts and Proposals; Barilla Center: Parma, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koester, U. Food Loss and Waste as an Economic and Policy Problem. Intereconomics 2014, 49, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörissen, J.; Priefer, C.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food Waste Generation at Household Level: Results of a Survey among Employees of two European Research Centers in Italy and Germany. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2695–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, P.; Campos, I.; Pires, I.; Vaz, S. Do Campo Ao Garfo, Desperdício Alimentar Em Portugal; CESTRAS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012; ISBN 978-989-20-3438-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitru, O.M.; Iorga, S.C.; Sanmartin, Á.M. Food Waste Impact on Romanian Households. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 26, 2207–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted Food: U.S. Consumers’ Reported Awareness, Attitudes, and Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, E. WRAP’s Vision is a World without Waste, Where Resources Are Used Sustainably; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Rickard, B.J.; Saputo, R.; Ho, S.-T. Food Waste: The Role of Date Labels, Package Size, and Product Category. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 55, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Alboni, F.; Falasconi, L. Quantities, Determinants, and Awareness of Households’ Food Waste in Italy: A Comparison between Diary and Questionnaires Quantities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Roe, B.E. Household Food Waste: Multivariate Regression and Principal Components Analyses of Awareness and Attitudes among U.S. Consumers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeutigam, K.-R.; Jörissen, J.; Priefer, C. The Extent of Food Waste Generation across EU-27: Different Calculation Methods and the Reliability of Their Results. Waste Manag. Res. J. Int. Solid Wastes Public Clean. Assoc. ISWA 2014, 32, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, O.J.; Syversen, F.; Stø, E. Edible Food Waste from Norwegian Households—Detailed Food Waste Composition Analysis among Households in Two Different Regions in Norway. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying Motivations and Barriers to Minimising Household Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for Household Food Waste with Special Attention to Packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Silvennoinen, K.; Hartikainen, H.; Heikkilä, L.; Reinikainen, A. Food Waste in the Finnish Food Chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B. Knowledge and Perception of Food Waste among German Consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, U.; Loy, J.; Ren, Y. Food Loss and Waste: Some Guidance. EuroChoices 2020, 19, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Agency. Austria Food Waste Statistics Austria Food Waste Legislation and Action in Austria; Zero Waste Austria: Wien, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Flemish Food Supply Chain Platform for Food Loss Food Waste and Food Losses. In Prevention and Valorisation; Flanders State of the Art: Brussel, Belgium, 2017.

- Danish Environmental Protection Agency. Kortlægning Af Sammenstaetningen Af Dagrenovation Og Kildesorteret Oranisk Affald Fra Husholdninger; Danish Environmental Protection Agency: Odense, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edjabou, M.E.; Petersen, C.; Scheutz, C.; Astrup, T.F. Food Waste from Danish Households: Generation and Composition. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxembourg Environment Ministry. 2020 Zusammenfassung der Studie. In Aufkommen, Behandlung und Vermeidung von Lebensmittelabfällen Im Großherzogtum Luxemburg 2018/2019; Eco-Conseil: Schengen, Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moora, H.; Urbel-Piirsalu, E.; Õunapuu, K. Toidujäätmete Ja Toidukao Teke Eesti Kodumajapidamistes Ja Toitlustusasutustes; Stockholm Environmental Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate General for the Environment. Preparatory Study on Food Waste across EU 27: Final Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G.; Buksti, M.; Cseh, B.; Juul, S.; Parry, A.; Politano, A.; Redlingshofer, B. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; FUSIONS: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; ISBN 978-91-88319-01-2. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, C.; Cobalea, H.B.; Serenella, S.; de Laurentiis, V.; European Commission, Joint Research Centre. Review of Studies on Food Waste Accounting at Member State Level; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; ISBN 978-92-76-09512-5. [Google Scholar]

- The Netherlands Nutrition Centre Foundation. Synthesis Report on Food Waste in Dutch Households in 2019; The Netherlands Nutrition Centre Foundation: The Hauge, The Netherland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Žitnik, M.; Vidic, T. Food among Waste; Republic of Slovenia Statistical Office: Ljubijana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff-Wrześniewska, A. The Pilot Study of Characteristics of Household Waste Generated in Suburban Parts of Rural Areas. J. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 16, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada National Waste Characterization Report. In The Composition of Canadian Residual Municipal Solid Waste; Environment and Climate Change Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canda, 2019.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2018 Wasted Food Report; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Beretta, C.; Hellweg, S. Lebensmittelverluste in der Schweiz: Umweltbelastung und Vermeidungspotential; Institut für Umweltingenieurwissenschaften: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, A.; Harris, B.; Fisher, K.; Forbes, H. UK Progress against Courtauld 2025 Targets and UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.3; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tonini, D.; Brogaard, L.K.-S.; Astrup, T.F. Food Waste Prevention in Denmark Identification of Hotspots and Potentials with Life Cycle Assessment; Danish Environmental Protection Agency: Odense, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Hartikainen, H.; Heikkilä, L.; Reinikainen, A. Food Waste Volume and Composition in Finnish Households. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADEME. Pertes et Gaspillages Alimentaires. l’état des Lieux et Leur Gestion par étapes de la Chaîne Alimentaire. 2016, 165. Available online: https://multimedia.ademe.fr/dossier-presse-etude-masses-pertes-gaspillages/index.html (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Cofresco Frischhalteprodukte Europa (Hg.). Save Food- Eine Initiative von Toppits. Das Wegwerfen von Lebensmitteln- Einstellungen und Verhaltensmuster. Quantitative Studie in deutschen Privathaushalten. Ergebnisse Deutschland. Cofresco Frischhalteprodukte Europa. Minden. 2011. Available online: https://www.toppits.de/portal/pics/Aktionen/Kampagne/Nachhaltig-Grillen-2020/Save-Food-Studie-Ergebnisse.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Costarelli, V.; Chroni, C. The Implications of Food Waste Generation on Climate Change: The Case of Greece. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasza, G.; Dorkó, A.; Kunszabó, A.; Szakos, D. Quantification of Household Food Waste in Hungary: A Replication Study Using the FUSIONS Methodology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokareva, T. Latvian Households’ Food Wasting in the Context of Eating Habits. Ph.D. Thesis, Latvia University of Agriculture, Jelgava, Latvia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van Dooren, C.; Janmaat, O.; Snoek, J.; Schrijnen, M. Measuring Food Waste in Dutch Households: A Synthesis of Three Studies. Waste Manag. 2019, 94, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca. Desperdicio de Alimentos de Los Hogares En España; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- Merritt, A. Naturvårdsverket Food Waste Volumes in Sweden; Swedish EPA: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; ISBN 978-91-620-8695-4. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Durchschnittliche Anzahl der Haushaltsmitglieder nach Bundesländern 2020 | Statista. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/200374/umfrage/anzahl-der-haushalte-in-deutschland-im-jahr-2010-nach-bundeslaendern/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Neumeier, S. Modellierung der Erreichbarkeit von Supermärkten und Discountern—Untersuchung zum Regionalen Versorgungsgrad mit Dienstleistungen der Grundversorgung; Thünen Institute: Braunschweig, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft. BMEL-Statistik: Lebensmitteleinzelhandel; Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft: Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti Soup: The Complex World of Food Waste Behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L.; Principato, L.; Laureti, T. Household Food Waste Behaviour in EU-27 Countries: A Multilevel Analysis. Food Policy 2015, 56, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out Food Waste Behaviour: A Survey on the Motivators and Barriers of Self-Reported Amounts of Food Waste in Households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Pratesi, C.A. Reducing Food Waste: An Investigation on the Behaviour of Italian Youths. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, W.K.; Turn, S.Q.; Flachsbart, P.G. Characterization of Food Waste Generators: A Hawaii Case Study. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, L.; Lorek, S. Enabling Sustainable Production-Consumption Systems. ERPN Public Policies Soc. Sub. Top. 2008, 33, 241–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, T.; Maeder, C. Organizational Ethnography. 2011. Available online: http://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/Publikationen/71206 (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft. Nationale Strategie zur Reduzierung der Lebensmittelverschwendung; Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft: Bonn/Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable Food Consumption: An Overview of Contemporary Issues and Policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Court of Auditors. European Report of the Court of Auditors for 2016; European Court of Auditors: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, R.; Marinova, N.; Lowe, J.; Brown, S.; Vellinga, P.; Gusmão, D.; Hinkel, J.; Tol, R. Sea-Level Rise and Its Possible Impacts given a “beyond 4 Degrees C World” in the Twenty-First Century. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft. Zu gut für die Tonne. Available online: https://www.zugutfuerdietonne.de/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- WWF. Deutschland Halbierung von Lebensmittelverlusten und -verschwendung in der EU bis 2030. In Die wichtigsten Massnahmen für schnelleren Fortschritt; WWF: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Food Item | Mass [kg] | Value [€] | Calorie [kcal] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potato | 100 | 0.20 | 77 |

| Bread | 100 | 1.00 | 240 |

| Butter | 100 | 0.50 | 717 |

| Disposal Of Food At Consumer Level |

|---|

Reasons for disposal

|

Causes

|

Driving forces of disposal—how does spoilage occur?

|

| Questionnaire N = 668 | Diary N = 59 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 43.1 (19.8) | 40.3 (17.4) |

| Gender | male | 36% | 21% |

| female | 64% | 79% | |

| Household manager | yes | 81% | 94% |

| no | 19% | 6% | |

| Household size | M | 2.4 persons | 2.3 persons |

| 1 PHH | 23% | 21% | |

| 2 PHH | 44% | 46% | |

| 3 PHH | 15% | 21% | |

| 4 PHH | 12% | 8% | |

| more than 5 PHH | 6% | 4% | |

| children > 14 years | 15% | 20% | |

| persons < 65 years | 20% | 14% | |

| Level of education | secondary modern school (school year 5 to 9 in Germany) | 6% | 4% |

| secondary school (school year 5 to 10 in Germany) | 12% | 2% | |

| final secondary-school examinations (qualifying for university) | 24% | 21% | |

| qualification/formation | 22% | 19% | |

| specialist | 5% | 0% | |

| bachelor | 9% | 25% | |

| master/state examination | 21% | 29% | |

| Net household income | <500 € | 9% | 8% |

| 500–1000 € | 21% | 29% | |

| 1000–2000 € | 23% | 16% | |

| 2000–3000 € | 19% | 20% | |

| 3000–4000 € | 14% | 10% | |

| >4000 € | 13% | 18% | |

| Food spending | <100 € | 3% | 4% |

| 100–300 € | 38% | 37% | |

| 300–500 € | 41% | 40% | |

| 500–1000 € | 17% | 17% | |

| >1000 € | 1% | 2% | |

| Diet | not vegetarian (meat-eating) | 80% | 67% |

| pescetarian (no meat, but fish-eating) | 4% | 13% | |

| vegetarian | 9% | 12% | |

| vegan | 2% | 4% | |

| others | 6% | 4% |

| Variables | Definition | Mean | S.D. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | |||||

| FWQ | Food Waste per week/person (kg) | 1.163578 | 0.8149499 | 0.05 | 5 |

| AFW | Avoidable Food Waste per week/person (kg) | 0.5983165 | 0.5825177 | 0.004 | 3.6 |

| Shopping Behaviour | |||||

| Frequency | Shopping frequency per week: 1 = less than 1×, 2 = 1–2×, 3 = 3–5×, 4 = daily | 2.466877 | 0.6904956 | 1 | 4 |

| Shoppinglist | Use of a shopping list: 1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = usually, 5 = always | 2.452681 | 1.134745 | 1 | 5 |

| Distance | Distance (km) to the nearest grocery shop. | 1.188368 | 1.855701 | 0.002 | 15 |

| Time | I try to spend as little time as possible shopping: 1 (not agree at all)–7 (totally agree about) | 3.933227 | 1.871337 | 1 | 7 |

| Quality | For high quality food, I am willing to pay a higher price: 1 (not agree at all)–7 (totally agree about) | 5.709524 | 1.564634 | 1 | 7 |

| Payment | I take special care to pay little for groceries: 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.347619 | 0.4765927 | 0 | 1 |

| Eating Habits | |||||

| Cooking | Cooking in household every week: 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.8280757 | 0.3776125 | 0 | 1 |

| Readytoeat | Consuming of ready-to-eat meals at home per week: 1 = 0×, 2 = 1–2×, 3 = 3–5×, 4 = daily | 1.583596 | 0.6483292 | 1 | 4 |

| Gorestaurant | Going to restaurant per week: 1 = 0×, 2 = 1–2×, 3 = 3–5×, 4 = daily | 1.768139 | 0.7317192 | 1 | 4 |

| Spoilage | |||||

| UseMHD | After the best-before date has expired, I will no longer consume the food: 1 (not agree at all)–7 (totally agree about) | 2.789889 | 1.896472 | 1 | 7 |

| Visual | Orientation on the appearance of the food: 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.7661927 | 0.4235857 | 0 | 1 |

| Smell | Orientation on the smell of the food: 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.8120063 | 0.3910161 | 0 | 1 |

| Taste | Orientation on the taste of the food: 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.6840442 | 0.465263 | 0 | 1 |

| Storage | I consciously buy less food in stock so that I have to throw away less: 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.6571429 | 0.4750414 | 0 | 1 |

| Involvement | |||||

| Interest | I am interested in the topic of food waste. 1 (not agree at all)–7 (totally agree about) | 4.310726 | 0.7217968 | 1 | 5 |

| Moral | It’s morally reprehensible to dispose of food. 1 (not agree at all)–7 (totally agree about) | 5.749206 | 1.522682 | 1 | 7 |

| Poison | I already had severe food poisoning. 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.2333333 | 0.4232887 | 0 | 1 |

| Grocery retail | |||||

| Discount | I would prefer if stores reduce individual products prices instead of offering volume discounts. 1 (not agree at all)–7 (totally agree about) | 4.283677 | 0.8225221 | 1 | 5 |

| Specialoffer | I take advantage of special offers thus I buy more than I consume. 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.1822504 | 0.3769448 | 0 | 1 |

| Singlebuy | I prefer to buy fruit, vegetables, and meat individually thus I can determine the amount by myself. 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.8288431 | 0.3769448 | 0 | 1 |

| Portionable | If I cannot buy fruit, vegetables, or meat individually, I often buy more than necessary. 0 = rejection, 1 = approval | 0.3708399 | 0.4834129 | 0 | 1 |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Age | Age of propositus (years) | 43.3 | 19.74585 | 11 | 87 |

| Female | 1 if propositus is female, 0 otherwise | 0.6396825 | 0.480474 | 0 | 1 |

| Hhhead | 1 if propositus is household manager, 0 otherwise | 0.8079365 | 0.3942357 | 0 | 1 |

| Diet | Nutrition 1 if Omnivore, 0 otherwise | 0.7968254 | 0.4026811 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | propositus level of education 1–7 the higher, the higher the level of education | 4.205742 | 1.86461 | 1 | 7 |

| Householdsize | Household size, persons per Household | 2.401587 | 1.335226 | 1 | 13 |

| Income | Total net income of the household 1 = >500 €, 2 = 500–1000 €, 3 = 1000–2000 €, 4 = 2000–3000 €, 5 = 3000–4000 €, 6 = <4000 € | 3.485 | 1.530909 | 1 | 6 |

| Children | Number of children; age ≤ 14 | 0.2587302 | 0.668181 | 0 | 4 |

| Elderly | Number of seniors; age ≥ 65 | 0.2936508 | 0.6363082 | 0 | 3 |

| Expenditure | Total grocery spending’s of the household: 1 = >100 €, 2 = 100–300 €, 3 = 300–500 €, 4 = 500–1000 €, 5 = <1000 € | 2.745192 | 0.8156629 | 1 | 5 |

| Statement | Mean | SD | I Do Not Agree (%) | I Neither Agree or Disagree (%) | I Agree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After the best-before date has expired, I do not consume food. | 2.8 | 1.9 | 69 | 11 | 21 |

| I decide to waste food based on its appearance. | 5.51 | 1.7 | 13 | 10 | 77 |

| I decide to waste food based on its smell. | 5.7 | 1.67 | 11 | 7 | 81 |

| I decide to waste food based on its taste. | 5.15 | 1.84 | 18 | 13 | 69 |

| For me, enjoyment comes first, so I dispose unsightly food. | 3.15 | 1.95 | 60 | 14 | 27 |

| If I have the slightest doubt about the quality and safety of food, I dispose it immediately. | 4.37 | 2.18 | 38 | 12 | 50 |

| I am often not sure whether the food is still safe to consume. | 3.08 | 1.79 | 62 | 15 | 23 |

| Statement | % |

|---|---|

| • I do not have time to process food. | 38% |

| • I cook too much; the leftovers are disposed. | 36% |

| • The package sizes are too big, so I buy more than I need. | 33% |

| • I go grocery shopping (for a week) and then my plans change. | 32% |

| • I am often uncertain if food is still ok for consumption. | 26% |

| • The groceries bought are already spoiled. | 13% |

| • I do not like the taste of the food. | 11% |

| • I buy too much because of special offers. | 11% |

| • I do not check my groceries before I go shopping. | 8% |

| • I shop groceries once a week and buy more than I actually need. | 6% |

| • I buy discounted items which best-before date is almost up. | 3% |

| Amount of FW per Person | Survey Study [kg] All Participants | Survey Study [kg] Diary Participants | Diary Study [kg] | Diary Study [€] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW per year | 59.6 kg | 62.1 | - | - |

| Unavoidable FW per year | 30.3 kg (51%) | 40.3 (65%) | - | - |

| Avoidable FW per year | 29.2 kg (49%) | 21.8 (35%) | 28.64 kg | 151.0 € |

| AFW | FWQ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | p > |t| | Coef. | Std. Err. | p > |t| | ||

| Shopping Behaviour | Frequency | 0.0567435 | 0.0442351 | 0.200 | 0.1101797 ** | 0.0502352 | 0.029 |

| Shopping list | −0.0437219 | 0.0324863 | 0.179 | −0.0959333 ** | 0.0352713 | 0.007 | |

| Distance | 0.0348813 ** | 0.0146014 | 0.017 | 0.0536469 ** | 0.0193817 | 0.006 | |

| Time | −0.0153615 | 0.01539 | 0.319 | −0.0063845 | 0.0183956 | 0.729 | |

| Quality | 0.0215182 | 0.016665 | 0.197 | −0.0015171 | 0.0207716 | 0.942 | |

| Payment | −0.1137951 ** | 0.0569415 | 0.046 | −0.0663974 | 0.0681687 | 0.330 | |

| R2 | 0.0701 | 0.1193 | |||||

| Eating Habits | Cooking | 0.1295911 * | 0.0662317 | 0.051 | 0.01574 | 0.1050921 | 0.881 |

| Ready to eat | 0.0410228 | 0.0425748 | 0.336 | 0.215158 ** | 0.0543633 | 0.000 | |

| Go restaurant | 0.0108869 | 0.0414721 | 0.793 | 0.0164217 | 0.0535087 | 0.759 | |

| R2 | 0.0500 | 0.1055 | |||||

| Spoilage | UseMHD | 0.0110118 | 0.0152312 | 0.470 | 0.0352006 ** | 0.0179512 | 0.050 |

| Visual | 0.1667701 ** | 0.0620412 | 0.007 | 0.054637 | 0.0971448 | 0.574 | |

| Smell | −0.0112435 | 0.0821608 | 0.891 | −0.0053929 | 0.1191314 | 0.964 | |

| Taste | 0.0796165 | 0.0596496 | 0.182 | 0.0664339 | 0.0756688 | 0.380 | |

| Storage | −0.1477875 * | 0.0770927 | 0.056 | −0.1915847 ** | 0.0723721 | 0.008 | |

| R2 | 0.0671 | 0.0981 | |||||

| Involvement | Interest | 0.0063523 | 0.0334971 | 0.850 | −0.0480371 | 0.0477593 | 0.315 |

| Moral | −0.013789 | 0.0183408 | 0.452 | −0.0214964 | 0.0242163 | 0.375 | |

| Poison | −0.0154726 | 0.0135059 | 0.252 | 0.0082132 | 0.0202242 | 0.685 | |

| R2 | 0.0472 | 0.0832 | |||||

| Grocery Retail | Discount | −0.0642994 ** | 0.0313529 | 0.041 | −0.0989234 ** | 0.0394768 | 0.012 |

| Special offer | 0.0033995 | 0.070435 | 0.962 | 0.1675357 * | 0.0919937 | 0.069 | |

| Single buy | −0.0644083 | 0.1149349 | 0.575 | 0.140901 | 0.0870997 | 0.106 | |

| Portionable | −0.0106574 | 0.0579162 | 0.854 | 0.1229374 * | 0.0685739 | 0.074 | |

| R2 | 0.0529 | 0.1004 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hermanussen, H.; Loy, J.-P.; Egamberdiev, B. Determinants of Food Waste from Household Food Consumption: A Case Study from Field Survey in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114253

Hermanussen H, Loy J-P, Egamberdiev B. Determinants of Food Waste from Household Food Consumption: A Case Study from Field Survey in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114253

Chicago/Turabian StyleHermanussen, Henrike, Jens-Peter Loy, and Bekhzod Egamberdiev. 2022. "Determinants of Food Waste from Household Food Consumption: A Case Study from Field Survey in Germany" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114253

APA StyleHermanussen, H., Loy, J.-P., & Egamberdiev, B. (2022). Determinants of Food Waste from Household Food Consumption: A Case Study from Field Survey in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114253