Factors Associated with Discrepancy of Child-Adolescent/Parent Reported Quality of Life in the Era of COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- Examine child-parent discrepancies in reporting HRQoL in a sample of French school-aged children from 8 to 18 years.

- (b)

- Investigate the potential factors associated with such discrepancies in the KIDSCREEN-27 scores.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Judgment Criterion

2.4.2. Descriptive and Comparative Analyses

2.4.3. Main Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Children/Teenager’s Sample

3.2. Characteristics of the Households and Parents’ Scores on the Various Questionnaires

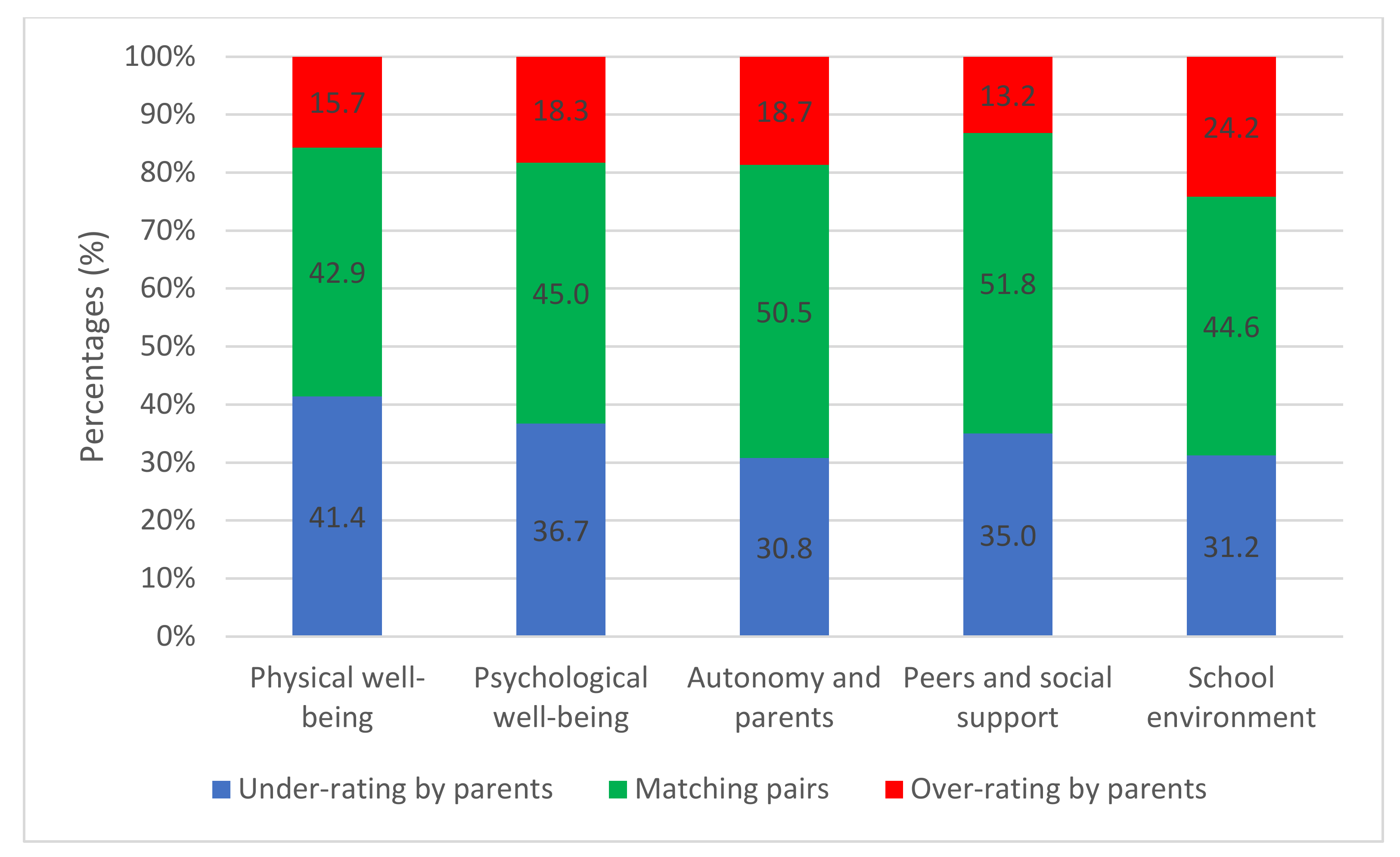

3.3. Child and Parents’ Reports of HRQoL and Child–Parent Discrepancy

3.4. Factors Associated with Child–Parent Discrepancies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| COR | Crude Odds Ratio |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale 7 |

| HRQoL | Health-related Quality of Life |

| KIDSCREEN-27 | Screening and Promotion for HRQoL in children and adolescents–a European Public Health Perspective |

| MCID | Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| MSPSS | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

| OE | Overevaluation |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PSS10 | Perceived Stress Scale |

| QoL | Quality Of Life |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis System |

| SF12 | Item-12 Short Form Survey |

| SF36 | Item-36 Short Form Survey |

| UE | Under Evaluation |

References

- Wallander, J.L.; Koot, H.M. Quality of life in children: A critical examination of concepts, approaches, issues, and future directions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Measuring Healthy Days n.d.:44. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/pdfs/mhd.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Masini, A.; Gori, D.; Marini, S.; Lanari, M.; Scrimaglia, S.; Esposito, F.; Campa, F.; Grigoletto, A.; Ceciliani, A.; Toselli, S.; et al. The Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life in a Sample of Primary School Children: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solans, M.; Pane, S.; Estrada, M.-D.; Serra-Sutton, V.; Berra, S.; Herdman, M.; Alonso, J.; Rajmil, L. Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: A systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2008, 11, 742–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raat, H.; Botterweck, A.M.; Landgraf, J.M.; Hoogeveen, W.C.; Essink-Bot, M.-L. Reliability and validity of the short form of the child health questionnaire for parents (CHQ-PF28) in large random school based and general population samples. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The child health and illness profile-adolescent edition: Assessing Well-Being in Group Homes or Institutions. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12092670 (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: Development, current application, and future advances. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2014, 23, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Rode, C.A. The PedsQL: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med. Care 1999, 37, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.C.; Huebner, C.E.; Connell, F.A.; Patrick, D.L. Adolescent quality of life, Part I: Conceptual and measurement model. J. Adolesc. 2002, 25, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierau, J.O.; Kann-Weedage, D.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Spiegelaar, L.; Jansen, D.E.M.C.; Vermeulen, K.M.; Reijneveld, S.; Hoofdakker, B.J.V.D.; Buskens, E.; Marle, M.E.V.D.A.-V.; et al. Assessing quality of life in psychosocial and mental health disorders in children: A comprehensive overview and appraisal of generic health related quality of life measures. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, C.; Varni, J.W. Health-related quality of life and symptom reporting: Similarities and differences between children and their parents. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmil, L.; López, A.R.; López-Aguilà, S.; Alonso, J. Parent-child agreement on health-related quality of life (HRQOL): A longitudinal study. Health Qual. Life. Outcomes 2013, 11, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothwal, V.K.; Bharani, S.; Mandal, A.K. Parent-Child Agreement on Health-Related Quality of Life in Congenital Glaucoma. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, A.S.; Knight, S.J. Proxy evaluation of health-related quality of life: A conceptual framework for understanding multiple proxy perspectives. Med. Care 2005, 43, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Nicolas, C.; Waters, E.; Cook, K.; Gibbs, L.; Gosch, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Parent-proxy and child self-reported health-related quality of life: Using qualitative methods to explain the discordance. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblin, E.; Audhuy, F.; Boillot, O.; Rivet, C.; Lachaux, A. Qualité de vie à long terme après transplantation hépatique chez l’enfant. Arch. Pédiatrie 2012, 19, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Mazur, J.; Tountas, Y.; Bruil, J.; Erhart, M.; Gosch, A.; Czimbalmos, A.; Czemy, L.; Power, M.; Auquier, P.; et al. The KIDSCREEN-52 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2008, 11, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jervaeus, A.; Kottorp, A.; Wettergren, L. Psychometric properties of KIDSCREEN-27 among childhood cancer survivors and age matched peers: A Rasch analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.A.; Otto, C.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Measuring health-related quality of life in young children with physical illness: Psychometric properties of the parent-reported KIDSCREEN-27. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2021, 31, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, A.; Burgers, Y.; de Veye, H.S.; Stegeman, I.; Breugem, C. Hearing-related quality of life, developmental outcomes and performance in children and young adults with unilateral conductive hearing loss due to aural atresia. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 142, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, H.T.; Haraldstad, K.; Helseth, S.; Skarstein, S.; Småstuen, M.C.; Rohde, G. Health-related quality of life is strongly associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem, loneliness, and stress in 14–15-year-old adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Plagg, B.; Mahlknecht, A.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents after the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Population-Based Survey in South Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, C.; Morse, R. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2001, 10, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan-Carlier, A.; Facione, J.; Speyer, E.; Rumilly, E.; Paysant, J. Quality of life and satisfaction after multilevel surgery in cerebral palsy: Confronting the experience of children and their parents. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 57, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, E.; Auto- et Hétéroévaluation de la Qualité de Vie des Enfants Implantés Cochléaires. EM-Consulte n.d. Available online: https://www.em-consulte.com/article/1033382/auto-et-heteroevaluation-de-la-qualite-de-vie-des- (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Qadeer, R.A.; Ferro, M.A. Child–parent agreement on health-related quality of life in children with newly diagnosed chronic health conditions: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2018, 23, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentenac, M.; Rapp, M.; Ehlinger, V.; Colver, A.; Thyen, U.; Arnaud, C. Disparity of child/parent-reported quality of life in cerebral palsy persists into adolescence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quitmann, J.; Rohenkohl, A.; Sommer, R.; Bullinger, M.; Silva, N. Explaining Parent-Child (Dis)Agreement in Generic and Short Stature-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life Reports: Do Family and Social Relationships Matter? Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsman, E.B.; Koel, M.L.; van Nispen, R.M.; van Rens, G.H. Interrater Reliability and Agreement between Children with Visual Impairment and Their Parents on Participation and Quality of Life. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattoe, J.N.T.; van Staa, A.; Moll, H.A. On Your Own Feet Research Group The Proxy Problem Anatomized: Child-Parent Disagreement in Health Related Quality of Life Reports of Chronically Ill Adolescents. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.H.; Liu, B.; Ullman, S.; Jadbäck, I.; Engström, K. Children’s Quality of Life Based on the KIDSCREEN-27: Child Self-Report, Parent Ratings and Child-Parent Agreement in a Swedish Random Population Sample. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitail, S.; Siméoni, M.-C.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Bruil, J.; Auquier, P. KIDSCREEN Group. Children proxies’ quality-of-life agreement depended on the country using the European KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobari, H.; Fashi, M.; Eskandari, A.; Villafaina, S.; Murillo-Garcia, Á.; Pérez-Gómez, J. Effect of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents and Children: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res, Public Health 2021, 18, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.-J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandek, B.; Ware, J.E.; Aaronson, N.K.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S.; Leplege, A.; Prieto, L.; et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Echelle de stress perçu INRS 2021. Available online: https://www.inrs.fr/media.html?refINRS=FRPS%204 (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Lesage, F.-X.; Berjot, S.; Deschamps, F. Psychometric properties of the French versions of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2012, 25, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Lagarde, S.; Barkate, G.; Dufournet, B.; Besancon, C.; Fonseca, A.T.-D.; Gavaret, M.; Bartolomei, F.; Bonini, F.; McGonigal, A. Rapid detection of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in epilepsy: Validation of the GAD-7 as a complementary tool to the NDDI-E in a French sample. Epilepsy Behav. EB 2016, 57, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, A.; Callahan, S.; Bouvard, M. Evaluation of the French version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support during the postpartum period. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Robitail, S.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Simeoni, M.-C.; Rajmil, L.; Bruil, J.; Power, M.; Duer, W.; Cloetta, B.; Csémy, L.; Mazur, J.; et al. Testing the structural and cross-cultural validity of the KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life questionnaire. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2007, 16, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Auquier, P.; Erhart, M.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Bruil, J.; Power, M.; Duer, W.; Cloetta, B.; Csémy, L.; et al. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life. Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2007, 16, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.R.; Sloan, J.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care 2003, 41, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger People Are More Vulnerable to Stress, Anxiety and Depression during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, B.J.; Lai, L.; Goldfield, G.; Sananes, R.; Longmuir, P.E. Psychosocial health and quality of life among children with cardiac diagnoses: Agreement and discrepancies between parent and child reports. Cardiol. Young 2017, 27, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, P.; Lawford, J.; Eiser, C. Parent-child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: A review of the literature. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2008, 17, 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Children N = 471 N (%)/Average (SD) | Parents N = 341 N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 219 (46.5) | 51 (15.0) |

| Female | 252 (53.5) | 290 (85.0) |

| Age | ||

| 8–11 | 188 (39.9) | |

| 12–14 | 121 (25.7) | |

| 15–18 | 162 (34.4) | |

| <30 | 2 (0.6) | |

| 30–39 | 85 (25.0) | |

| 40–49 | 217(63.6) | |

| >50 | 37 (10.8) | |

| Socio-professional category | ||

| Farmers-operators | 1 (0.3) | |

| Artisans, shopkeepers and company managers | 8 (2.3) | |

| Managers and higher intellectual professions | 84 (24.6) | |

| Intermediate professions | 52 (15.2) | |

| Employees | 142 (41.6) | |

| Workers | 10 (2.9) | |

| Retired | 4 (1.2) | |

| Other persons not working | 40 (11.7) | |

| Highest diploma | ||

| No diploma/primary school certificate/secondary school certificate, CAP, BEP or equivalent | 56 (16.4) | |

| Baccalaureate, vocational certificate or equivalent | 65 (19.1) | |

| Higher education diploma (minimum 2 years of higher education) | 220 (64.5) | |

| Professional activity | ||

| Full-time | 214 (63.6) | |

| Half-time/part-time | 80 (23.7) | |

| Job search/studies | 29 (8.6) | |

| Disability/retirement | 15 (4.5) |

| Full Sample N = 471 N (%)/Average (SD) | Primary School Students N = 187 N (%)/Average (SD) | Middle School Students N = 171 N (%)/Average (SD) | High School Students N = 113 N (%)/Average (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Male Female Age | 219 (46.5) 252 (53.5) 12.9 (2.9) | 92 (49.2) 95 (50.8) 9.9 (0.8) | 94 (55.0) 77 (45.0) 13.5 (1.24) | 33 (29.2) 80 (70.8) 17.0 (0.87) | <0.0001 |

| Focus at home for homework Not at all difficult A little difficult Difficult Very difficult | 143 (30.5) 159 (33.9) 94 (20.1) 73 (15.6) | 53 (28.3) 51 (27.3) 44 (23.5) 39 (20.9) | 55 (32.4) 64 (37.6) 28 (16.5) 23 (13.5) | 35 (31.3) 44 (39.3) 22 (19.6) 11 (9.8) | 0.0431 |

| Homework time +4h/day every day Between 2h and 4h/day every day -2h/day every day -1h/day every day | 137 (29.4) 209 (44.8)97 (20.8) 23 (4.9) | 39 (21.0) 98 (52.7) 42 (22.6) 7 (3.8) | 57 (33.7) 64 (37.9) 39 (23.1) 9 (5.3) | 41 (36.9) 47 (42.3) 16 (14.4) 7 (6.3) | 0.0131 |

| Have to be home-schooled Not at all difficult A little difficult Difficult Very difficult | 197 (42.2) 140 (30.0) 75 (16.0) 55 (11.8) | 77 (41.6) 48 (25.9) 35 (18.9) 25 (13.5) | 79 (46.5) 51 (30.0) 17 (10.0) 23 (13.5) | 41 (36.6) 41 (36.6) 23 (20.5) 7 (6.3) | 0.0267 |

| Fear of going out and having the COVID-19 Not at all A little A lot Enormously | 210 (44.9) 165 (35.2) 55 (11.7) 38 (8.1) | 79 (42.2) 48 (25.7) 34 (18.2) 26 (13.9) | 82 (48.5) 67 (39.6) 14 (8.3) 6 (3.6) | 49 (43.8) 50 (44.6) 7 (6.3) 6 (5.4) | <0.0001 |

| Exit outside the dwelling Several times a day, almost every day Once a day, almost every day Several times a week but not every day Approximately once a week Less than once a week Never | 51 (10.9) 91 (19.4) 77 (16.4) 59 (12.6) 87 (18.6) 104 (22.2) | 24 (12.8) 34 (18.2) 32 (17.1) 24 (12.8) 30 (16.0) 43 (23.0) | 21 (12.3) 36 (21.1) 27 (15.8) 19 (11.1) 31 (18.1) 37 (21.6) | 6 (5.4) 21 (18.9) 18 (16.2) 16 (14.4) 26 (23.4) 24 (21.6) | 0.6982 |

| Noises outside the residence Yes No | 54 (11.5) 417 (88.5) | 24 (12.8) 163 (87.2) | 16 (9.4) 155 (90.6) | 14 (12.4) 99 (87.6) | 0.5518 |

| Noises inside the residence Yes No | 43 (9.1) 428 (90.9) | 17 (9.1) 170 (90.9) | 16 (9.4) 155 (90.6) | 10 (8.8) 103 (91.2) | 0.9892 |

| Tensions or conflicts with neighbors Yes No | 11 (2.3) 460 (97.7) | 4 (2.1) 183 (97.9) | 4 (2.3) 167 (97.7) | 3 (2.7) 110 (97.3) | 0.9597 |

| Tensions and conflicts at home Yes No | 137 (29.1) 334 (70.9) | 47 (25.1) 140 (74.9) | 55 (32.2) 116 (67.8) | 35 (31.0) 78 (69.0) | 0.3017 |

| Difficulty isolating at home Yes No | 62 (13.2) 409 (86.8) | 20 (10.7) 167 (89.3) | 25 (14.6) 146 (85.4) | 17 (15.0) 96 (85.0) | 0.4532 |

| Parents | ||

|---|---|---|

| N = 341 | ||

| N | %/Average (SD) | |

| Parents’ scores | ||

| MSPSS total score | 341 | 5.5 (1.2) |

| MSPSS subscales | ||

| Family | 341 | 5.5 (1.3) |

| Friends | 341 | 5.3 (1.4) |

| Significant other | 341 | 5.7 (1.2) |

| GAD-7 total score | 341 | 5.2 (4.7) |

| Normal anxiety (0–4) | 170 | 49.9 |

| Average anxiety (5–9) | 108 | 31.7 |

| Moderate anxiety (10–14) | 47 | 13.8 |

| High anxiety (15–21) | 16 | 4.7 |

| PSS-10 total score | 341 | 14.0 (7.8) |

| Low stress (0–13) | 171 | 50.1 |

| Moderate stress (14–26) | 151 | 44.3 |

| Severe stress (27–40) | 19 | 5.6 |

| BRS total score | 341 | 3.6 (0.8) |

| <3 | 65 | 19.1 |

| ≥3 | 276 | 80.9 |

| SF12 mental health score | 341 | 56.6 (16.5) |

| SF12 physical health score | 341 | 70.3 (12.7) |

| Households | ||

| Type of accommodation | 340 | |

| Apartment/mobile home | 68 | 20 |

| House | 272 | 80 |

| Access to a private outside space | 341 | |

| Private balcony, courtyard or terrace | 38 | 11.1 |

| Private domestic garden | 270 | 79.2 |

| Courtyard or garden for collective use | 11 | 3.2 |

| No access | 22 | 6.5 |

| Someone at home had COVID-19 | 341 | |

| Confirmed and hospitalized cases | 3 | 0.9 |

| Confirmed and non-hospitalized cases | 7 | 2.1 |

| Suspected cases | 32 | 9.4 |

| No | 299 | 87.7 |

| Home location | 339 | |

| Urban area | 131 | 38.6 |

| Rural area | 208 | 61.4 |

| Family structure | 339 | |

| Single parent | 62 | 18.3 |

| Original couple | 230 | 67.8 |

| Parent + partner | 47 | 13.9 |

| Full Sample N = 471 Average (SD) | Primary School Students N = 187 Average (SD) | Middle School Students N = 171 Average (SD) | High School Students N = 113 Average (SD) | Parents N = 471 Average (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: Physical well-being | 45.9 (10.3) | 49.4 (9.6) | 44.9 (10.5) | 41.8 (9.4) | 42.9 (9.4) | <0.0001 |

| Dimension 2: Psychological well-being | 48.8 (10.0) | 51.2 (9.2) | 48.2 (10.3) | 45.7 (9.8) | 46.9 (11.3) | 0.0054 |

| Dimension 3: Autonomy and parents | 47.7 (11.3) | 46.3 (9.6) | 47.8 (11.8) | 49.7 (12.7) | 46.2 (12.2) | 0.0610 |

| Dimension 4: Peers and social support | 36.4 (14.7) | 31.5 (15.8) | 37.8 (12.6) | 42.4 (13.3) | 32.9 (14.9) | 0.0003 |

| Dimension 5: School environment | 48.2 (10.2) | 50.0 (9.8) | 47.0 (10.1) | 46.9 (10.4) | 47.2 (10.5) | 0.1275 |

| Bivariable Multinomial Logistic Regression | Multivariable Multinomial Logistic Regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Dimension 1: Physical well-being | R2 = 0.08, H&L = 0.41 | |||||

| Children: Tensions and conflicts with neighbors (Yes vs. No) Parents: SF12 Mental health score (Ref: > Median score) Home location (Rural area vs. Urban area) Someone at home had COVID-19 (Ref: No) Suspected cases | UE: 1.04 OE: 4.81 UE: 1.58 OE: 1.14 UE: 1.68 OE: 1.35 UE: 2.53 OE: 1.11 | 0.21–5.20 1.12–20.65 1.06–2.34 0.67–1.95 1.11–2.53 0.78–2.35 1.27–5.03 0.38–3.24 | 0.9652 0.0347 0.0244 0.6320 0.0134 0.2810 0.0081 0.8461 | 0.95 5.04 1.71 0.99 1.76 1.41 2.69 0.93 | 0.18–4.91 1.14–22.27 1.13–2.58 0.56–1.75 1.15–2.69 0.80–2.50 1.32–5.47 0.29–2.99 | 0.9515 0.0329 0.0110 0.9722 0.0088 0.2364 0.0063 0.9050 |

| Dimension 2: Psychological well-being | R2 = 0.1, H&L = 0.71 | |||||

| Children: Gender (Male vs. Female) Parents: Professional activity (Ref: Job search /studies /disability /retirement) Full time Half-time/part-time MSPSS significant others score (Ref: ≤ Median score) | UE: 1.91 OE: 1.13 UE: 0.93 OE: 3.75 UE: 1.48 OE: 7.01 UE: 0.92 OE: 2.20 | 1.27–2.86 0.68–1.87 0.51–1.71 1.10–12.84 0.74–2.96 1.95–25.24 0.60–1.41 1.32–3.66 | 0.0019 0.6413 0.8254 0.0349 0.2648 0.0029 0.7040 0.0024 | 2.00 1.07 0.81 6.28 1.32 11.61 0.95 2.38 | 1.32–3.04 0.63–1.82 0.44–1.51 1.43–27.53 0.65–2.68 2.52–53.63 0.61–1.47 1.40–4.04 | 0.0011 0.7984 0.5163 0.0148 0.4441 0.0017 0.8049 0.0014 |

| Dimension 3: Autonomy and parents | R2 = 0.08, H&L = 0.96 | |||||

Children: Noises inside the residence (Yes vs. No) Parents: Highest degree (Ref: No diploma/primary school certificate/secondary school diploma, CAP, BEP or equivalent) Baccalaureate, vocational certificate or equivalent Family structure (Ref: Parent + partner) Single parent Original couple | UE: 2.41 OE: 2.05 UE: 2.15 OE: 2.61 UE: 3.88 OE: 1.18 UE: 2.48 OE: 0.86 | 1.17–4.98 0.88–4.81 1.08–4.31 1.07–6.37 1.67–9.01 0.51–2.70 1.19–5.17 0.45–1.65 | 0.0171 0.0978 0.0303 0.0346 0.0016 0.7012 0.0157 0.6487 | 2.45 2.16 2.05 3.26 4.00 1.00 2.50 0.82 | 1.17–5.12 0.92–5.10 1.00–4.25 1.26–8.41 1.70–9.40 0.42–2.41 1.19–5.27 0.42–1.60 | 0.0172 0.0784 0.0496 0.0147 0.0015 0.9903 0.0160 0.5686 |

| Dimension 4: Peers and social support | R2 = 0.06, H&L = 0.93 | |||||

Children: Education level (Ref: Primary school) Middle school High school Parents: Home location (Urban area vs. Rural area) | UE: 1.59 OE: 3.72 UE: 1.69 OE: 3.87 UE: 1.50 OE: 2.16 | 1.01–2.51 1.79–7.70 1.01–2.83 1.76–8.51 1.00–2.26 1.22–3.82 | 0.0471 0.0004 0.0453 0.0008 0.0521 0.0081 | 1.60 3.85 1.55 3.24 1.45 2.08 | 1.01–2.53 1.85–8.03 0.92–2.62 1.45–7.26 0.95–2.21 1.15–3.75 | 0.0466 0.0003 0.1001 0.0042 0.0834 0.0153 |

| Dimension 5: School environment | R2 = 0.07, H&L = 0.71 | |||||

| Parents: SF12 Physical health score (Ref: > Median score) Access to a private outside space (Ref: Private domestic garden Courtyard or garden for collective use No access | UE: 1.77 OE: 0.99 UE:<0.001 OE: 5.80 UE: 2.65 OE: 1.69 | 1.15–2.71 0.63–1.57 <0.001–>999.99 1.53–21.96 1.08–6.53 0.59–4.81 | 0.0087 0.9862 0.9812 0.0096 0.0334 0.3240 | 1.77 1.11 <0.001 5.89 3.09 1.90 | 1.14–2.75 0.69–1.79 <0.001–>999.99 1.54–22.45 1.20–7.95 0.65–5.60 | 0.0108 0.6517 0.9811 0.0095 0.0192 0.2414 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeanbert, E.; Baumann, C.; Todorović, A.; Tarquinio, C.; Rousseau, H.; Bourion-Bédès, S. Factors Associated with Discrepancy of Child-Adolescent/Parent Reported Quality of Life in the Era of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114359

Jeanbert E, Baumann C, Todorović A, Tarquinio C, Rousseau H, Bourion-Bédès S. Factors Associated with Discrepancy of Child-Adolescent/Parent Reported Quality of Life in the Era of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114359

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeanbert, Elodie, Cédric Baumann, Anja Todorović, Cyril Tarquinio, Hélène Rousseau, and Stéphanie Bourion-Bédès. 2022. "Factors Associated with Discrepancy of Child-Adolescent/Parent Reported Quality of Life in the Era of COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114359

APA StyleJeanbert, E., Baumann, C., Todorović, A., Tarquinio, C., Rousseau, H., & Bourion-Bédès, S. (2022). Factors Associated with Discrepancy of Child-Adolescent/Parent Reported Quality of Life in the Era of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114359