The Construction of Image Reference Points and Text Appeals Information Tailoring in Promoting Diners’ Public Environment Maintenance Behavior Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Feasibility and Desirability Appeals in Information Tailoring

2.2. Reference Points in Information Tailoring

2.3. Construction of Feasibility, Desirability and Reference Points in Information Tailoring

2.4. The Mediating Role of Perceived Environmental Responsibility in Pro-Environmental Behavior Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Participants

3.2. Stimulus Material Design

3.3. Experimental Measures

3.4. Experimental Procedures

4. Result

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

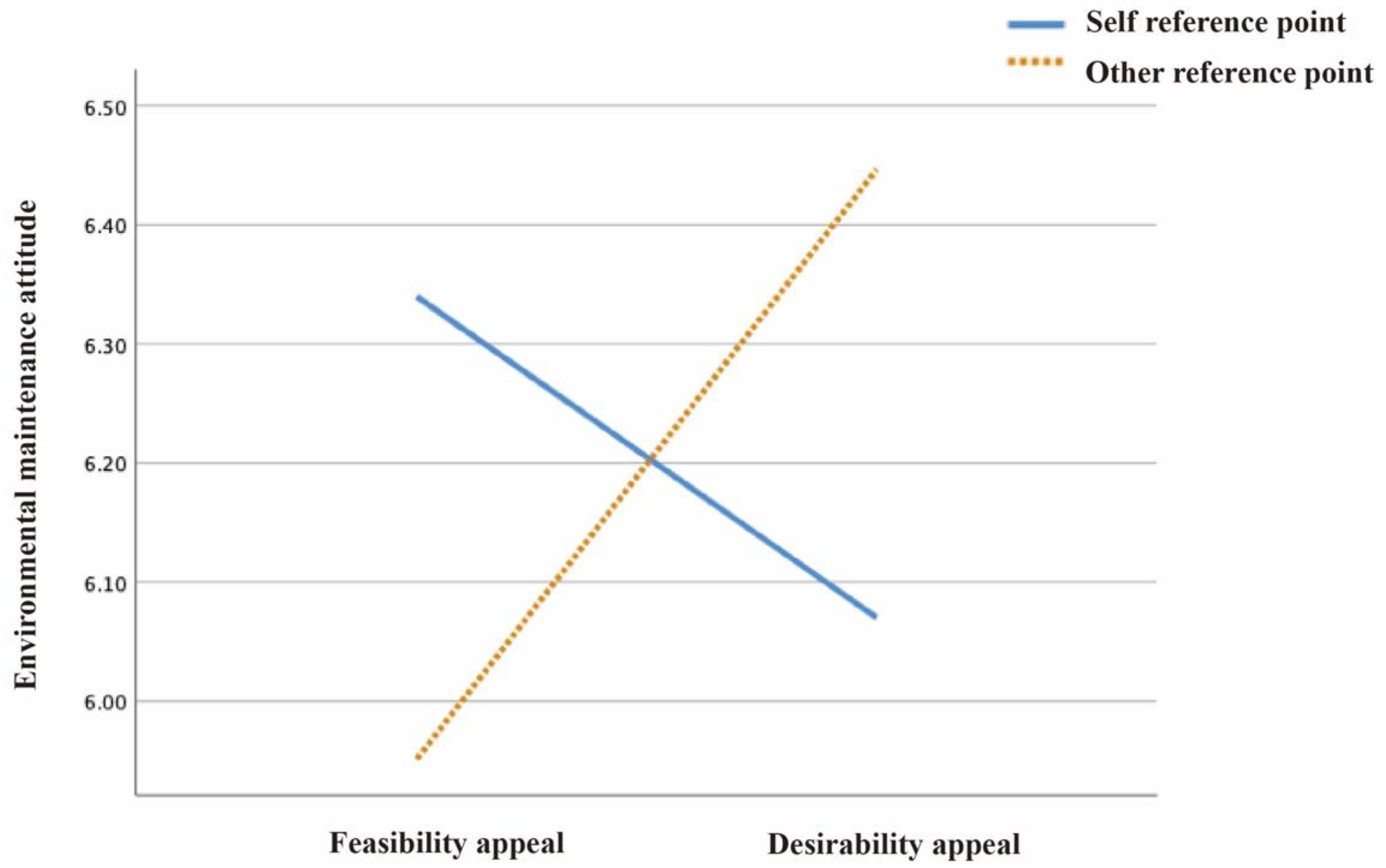

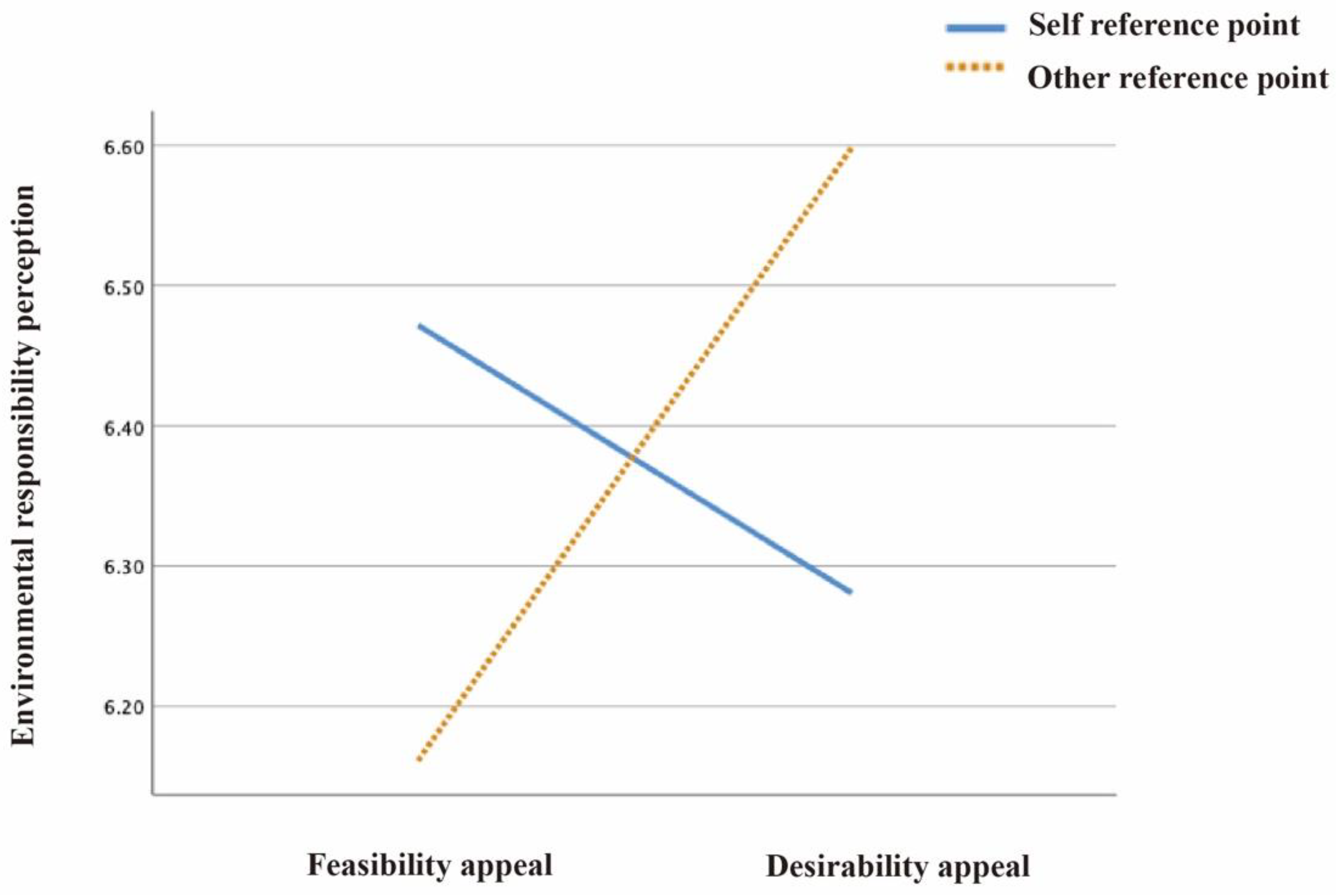

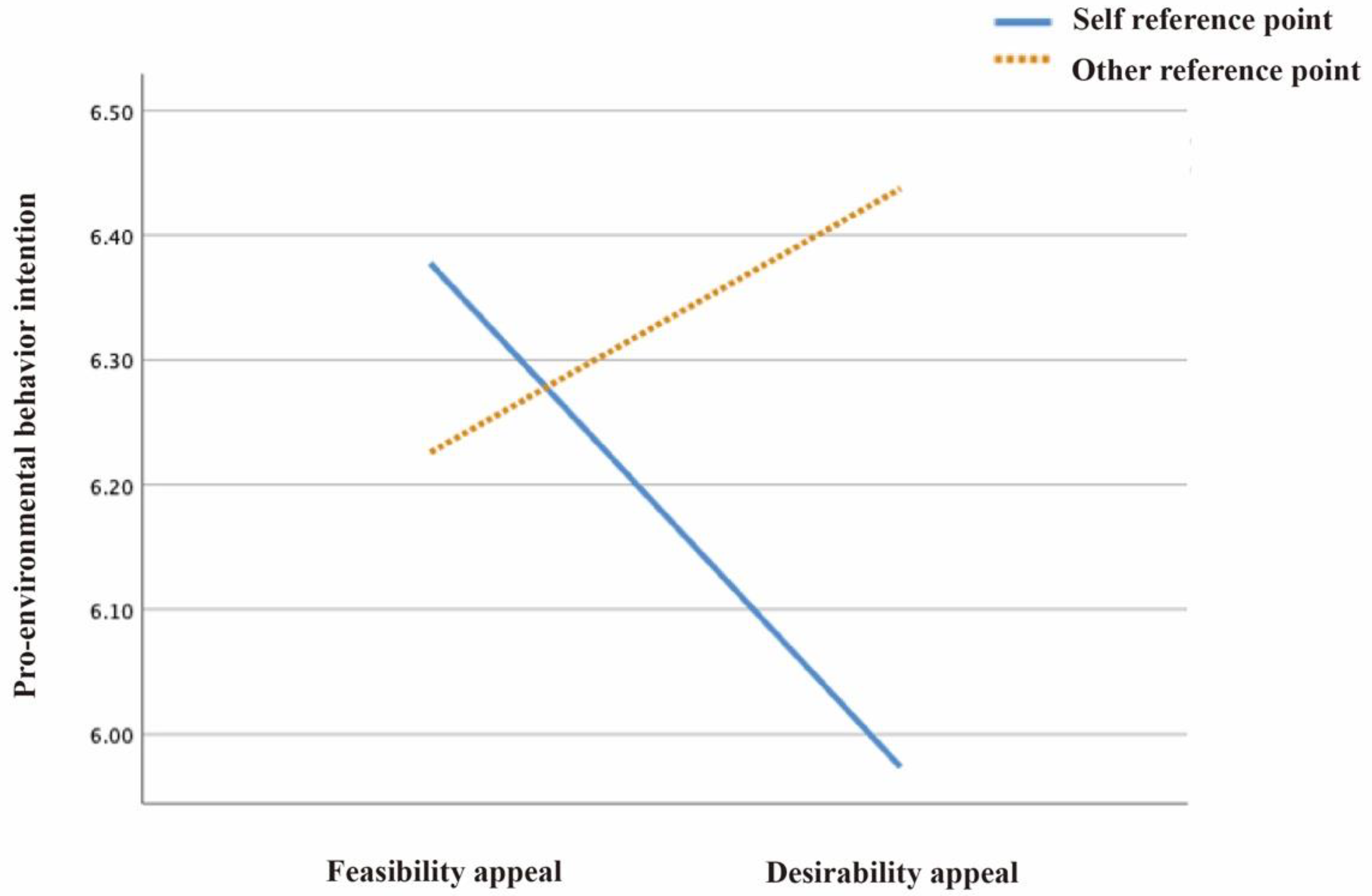

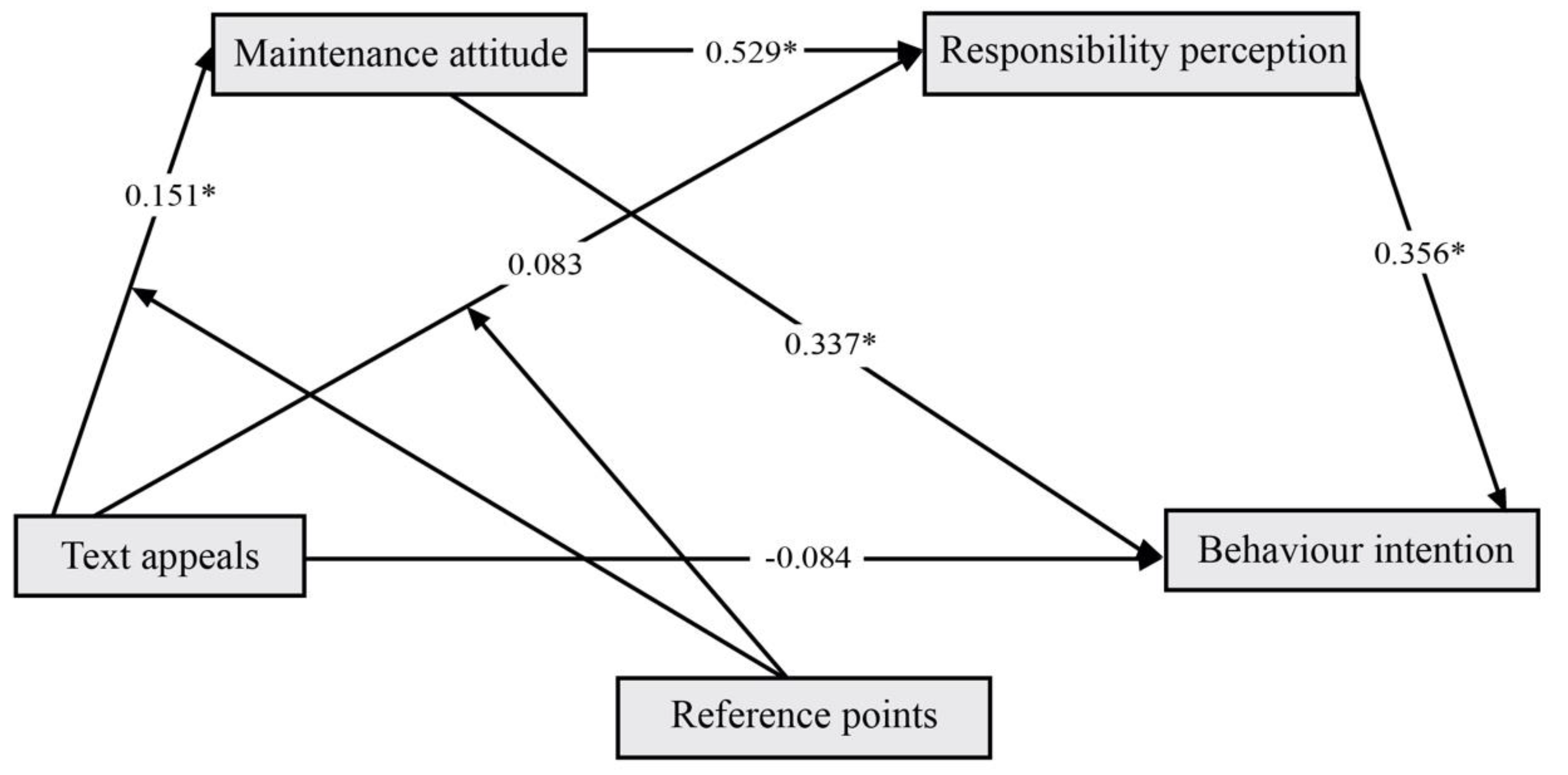

4.3. Conditional Process Analysis

- (a)

- For environmental maintenance attitudes, image reference points and text appeals had an interactive effect on attitudes, and image reference points moderated text appeals (β = 0.151, BootLLCI = 0.023 to BootULCI = 0.278);

- (b)

- For environmental responsibility perception, environmental maintenance attitude had a mediating effect (β = 0.529, BootLLCI = 0.325 to BootULCI = 0.755);

- (c)

- For pro-environmental behavior intentions, both environmental maintenance attitudes and environmental responsibility perceptions had a mediating effect (β = 0.337, BootLLCI = 0.179 to BootULCI = 0.548), (β = 0.356, BootLLCI = 0.179 to BootULCI = 0.523). The data analysis results showed that H2, H3 are correct. There are two paths for the realization of pro-environmental behavior intentions. In the first pathway, mediated by environmental maintenance attitudes alone, image reference points moderated the effects of text appeals on environmental maintenance attitudes (β = 0.051, BootLLCI = 0.152 to BootULCI = 0.214), and then influenced pro-environmental behavioral intentions. The second pathway was mediated by environmental maintenance attitudes and environmental responsibility perceptions. Here, image reference points moderated text appeals of environmental maintenance attitudes (β = 0.028, BootLLCI = 0.007 to BootULCI = 0.131), which affected environmental responsibility and perceived pro-environmental behavior intentions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vardoulakis, S.; Salmond, J.; Krafft, T.; Morawska, L. Urban Environmental Health Interventions towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenhaute, H.; Gellynck, X.; De Steur, H. COVID-19 Safety Measures in the Food Service Sector: Consumers’ Attitudes and Transparency Perceptions at Three Different Stages of the Pandemic. Foods 2022, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollust, S.E.; Fowler, E.F.; Niederdeppe, J. Television News Coverage of Public Health Issues and Implications for Public Health Policy and Practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Trafiałek, J.; Wiatrowski, M.; Głuchowski, A. An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of European Street Food Vendors and a Preliminary Estimation of Food Safety for Consumers, Conducted in Paris. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirawati, L.; Kriswibowo, A.; Nurani, F.P. Indonesia canteen sanitation policy implementation in College campus as a step to optimizing the public health sector. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2019, 90, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, E.; Seo, S.; Choi, J.; Pool, V.; Ilic, S. Assessment of Food Safety at University Food Courts Using Surveys, Observations, and Microbial Testing. Food Control 2019, 103, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, A.B.; Lavik, R. Eating out: A multifaceted activity in contemporary Norway. Food Cult. Soc. 2010, 13, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, E.; Kaskela, J.; Keto-Timonen, R.; Lundén, J. Results of Routine Inspections in Restaurants and Institutional Catering Establishments Associated with Foodborne Outbreaks in Finland. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satow, Y.E.; Inciardi, J.F.; Wallace, S.P. Factors Used by Restaurant Customers to Predict Sanitation Levels. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2009, 12, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Bachman, J.R. Examining Customer Perceptions of Restaurant Restroom Cleanliness and Their Impact on Satisfaction and Intent to Return. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview of Public Health and Social Measures in the Context of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/overview-of-public-health-and-social-measures-in-the-context-of-covid-19 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Barber, N.; Scarcelli, J.M. Enhancing the Assessment of Tangible Service Quality through the Creation of a Cleanliness Measurement Scale. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2010, 20, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Cleanliness Satisfaction Survey 2021. Available online: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/3342/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Morandi, E. The “Dining Table Revolution” in China: The Question Read through the Lens of Newspapers. In Studi e Saggi; Castorina, M., Cucinelli, D., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2021; Volume 233, pp. 161–176. ISBN 978-88-551-8505-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, R.F.; Gough, A.; O’Kane, N.; McKeown, G.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Walker, T.; McKinley, M.; Lee, M.; Kee, F. Ethical Issues in Social Media Research for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiesen, S.L.; Aadal, L.; Uldbæk, M.L.; Astrup, P.; Byrne, D.V.; Wang, Q.J. Music Is Served: How Acoustic Interventions in Hospital Dining Environments Can Improve Patient Mealtime Wellbeing. Foods 2021, 10, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indig, D.; Lee, K.; Grunseit, A.; Milat, A.; Bauman, A. Pathways for Scaling up Public Health Interventions. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungku Fatimah, U.Z.A.; Boo, H.C.; Sambasivan, M.; Salleh, R. Foodservice Hygiene Factors—The Consumer Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhasawade, V.; Elghafari, A.; Duncan, D.T.; Chunara, R. Role of the Built and Online Social Environments on Expression of Dining on Instagram. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Lifestyle Receptivity Survey 2021 Run in 12 Countries; Follow-Up to 2010 Poll. Available online: https://www.group.dentsu.com/en/news/release/000564.html (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Temporal Construal. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Wakslak, C. Construal Levels and Psychological Distance: Effects on Representation, Prediction, Evaluation, and Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houwelinggen, G.; Stam, D.; Giessner, S. So close and yet so far away: A psychological distance account of the effectiveness of leader appeals. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, R.W.; Trudel, R.; White, K. Focusing on the Forest or the Trees: How Abstract versus Concrete Construal Level Predicts Responses to Eco-Friendly Products. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 57, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.R.; Baek, T.H.; Yoon, S.; Kim, Y. Is That Coffee Mug Smiling at Me? How Anthropomorphism Impacts the Effectiveness of Desirability vs. Feasibility Appeals in Sustainability Advertising. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevincer, A.T.; Oettingen, G. Alcohol Intake Leads People to Focus on Desirability Rather than Feasibility. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, D.; Chen, X.; Chu, X.-Y. “I Want It! Can I Get It?” How Product-Model Spatial Distance and Ad Appeal Affect Product Evaluations. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhong, J.; Guo, G.; Chen, F. The Impact of Reduced Visibility Caused by Air Pollution on Construal Level. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Bang, H.; Choi, D.; Kim, K. Slow versus Fast: How Speed-Induced Construal Affects Perceptions of Advertising Messages. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Sung, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, D.; Sung, Y. Are You on Timeline or News Feed? The Roles of Facebook Pages and Construal Level in Increasing Ad Effectiveness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugrul, T.O.; Lee, E.-M. Promoting Charitable Donation Campaigns on Social Media. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, S.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L.; Labyt, C. The Impact of Media Multitasking on the Cognitive and Attitudinal Responses to Television Commercials: The Moderating Role of Type of Advertising Appeal. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tang, B.; Nawijn, J. How Tourism Activity Shapes Travel Experience Sharing: Tourist Well-Being and Social Context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, E.; Wakslak, C.J.; Trope, Y.; Novemsky, N. Why Feasibility Matters More to Gift Receivers than to Givers: A Construal-Level Approach to Gift Giving. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.M.; Wang, Y.; Ge, L.; Shi, G.; Yao, S. Asymmetric Effects of Regulatory Focus on Expected Desirability and Feasibility of Embracing Self-Service Technologies. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ghosh, T. How Does a Brand’s Psychological Distance in an Advergame Influence Brand Memory of the Consumers? J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1449–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jeong, E.; Olson, E.D.; Evans, G. Investigating the Effect of Message Framing on Event Attendees’ Engagement with Advertisement Promoting Food Waste Reduction Practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, S.; Fernandes, J.; Wang, W. The Effects of Gain Versus Loss Message Framing and Point of Reference on Consumer Responses to Green Advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2015, 36, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; DeSalvo, D. The Effect of Message Framing and Focus on Reducing Food Waste. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 650–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xue, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Niu, J.; Lai, Y.; Hou, C. Interplay of Message Frame and Reference Point on Recycled Water Acceptance in Green Community: Evidence from an Eye-Tracking Experiment. Buildings 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Siemer, W.F.; Baumer, M.S.; Decker, D.J. Exploring the Role of Gain versus Loss Framing and Point of Reference in Messages to Reduce Human–Bear Conflicts. Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 55, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nab, M.; Jansma, S.; Gosselt, J. Tell Me What Is on the Line and Make It Personal: Energizing Dutch Homeowners through Message Framing. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loroz, P.S. The Interaction of Message Frames and Reference Points in Prosocial Persuasive Appeals. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Cao, E. Can Reference Points Explain Vaccine Hesitancy? A New Perspective on Their Formation and Updating. Omega 2021, 99, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karle, H.; Schumacher, H. Advertising and Attachment: Exploiting Loss Aversion through Prepurchase Information. RAND J. Econ. 2017, 48, 927–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Adamowicz, W.L.; Veeman, M.M. Labeling Context and Reference Point Effects in Models of Food Attribute Demand. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 88, 1034–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, J.A.; York, A. Framing Information to Enhance Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, E.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. Politeness and Psychological Distance: A Construal Level Perspective. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.E.; Bargh, J.A. Keeping One’s Distance: The Influence of Spatial Distance Cues on Affect and Evaluation. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroditsky, L. Comparison and the Development of Knowledge. Cognition 2007, 102, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Anan, Y.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; Algom, D. Automatic Processing of Psychological Distance: Evidence from a Stroop Task. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2007, 136, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; McCrea, S.M.; Sherman, S.J. The Effect of Level of Construal on the Temporal Distance of Activity Enactment. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Anan, Y.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The Association between Psychological Distance and Construal Level: Evidence from an Implicit Association Test. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2006, 135, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Xie, X.; Xu, J. Desirability or Feasibility: Self–Other Decision-Making Differences. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M.; Yalch, R.F. How a Maximizing Orientation Affects Trade-offs between Desirability and Feasibility: The Role of Outcome- versus Process-focused Decision Making. J. Behav. Dec. Mak. 2020, 33, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Yoon, S.; Chun, S.; Park, C.; Kim, K. How Liberals and Conservatives Respond to Feasibility and Desirability Appeals in Anti-Tobacco Campaigns. Asian J. Commun. 2019, 29, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Gao, J. Effect of Green Consumption Value on Consumption Intention in a Pro-Environmental Setting: The Mediating Role of Approach and Avoidance Motivation. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402090207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. The Influence Mechanism of Environmental Anxiety on Pro-environmental Behaviour: The Role of Self-discrepancy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Jeong, D.; Chon, J. The Impact of the Risk Perception of Ocean Microplastics on Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavior Intention. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 144782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E.; Macias-Zambrano, L.; Guzman, I.; Carpio, A.J.; Tabernero, C. The Role of Implicit Theories about Climate Change Malleability in the Prediction of Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-C.; Wu, C.-C. The Effect of Message Framing on Pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions: An Information Processing View. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, N.; Nisar, T.; Knox, D.; Prabhakar, G. The Influences of Cleanliness and Employee Attributes on Perceived Service Quality in Restaurants in a Developing Country. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Garg, P.; Singh, S. Pro-Environmental Purchase Intention towards Eco-Friendly Apparel: Augmenting the Theory of Planned Behavior with Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Environmental Concern. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R. The Moderating Influence of Environmental Consciousness and Recycling Intentions on Green Purchase Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X. Landscape and Unique Fascination: A Dual-Case Study on the Antecedents of Tourist Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions. Land 2022, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetti, M.; Melotti, G.; Vespa, M.; Cappabianca, F.; Troilo, F.; Placentino, M.P. Predicting Recycling in Southern Italy: An Exploratory Study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-T.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; Kim, P.B. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents of pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention of Tourists and Hospitality Consumers. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Steinke, A.; Dewitte, S. The Pro-Environmental Behavior Task: A Laboratory Measure of Actual pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 56, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W.; Lenhausen, M.R.; Hopwood, C.J. Proenvironmental Attitudes Predict Proenvironmental Consumer Behaviors over Time. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham, J.R.; Minihan, S.; Winch, C.J. Imagining as an Observer: Manipulating Visual Perspective in Obsessional Imagery. Cogn. Res. 2019, 43, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, S.; Lim, H.; Lyu, J. “I” or “She/He”? The Effects of Visual Perspective on Consumers’ Evaluation of Brands’ Social Media Marketing: From Imagery Fluency Perspective. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, M.; Erdogan, B.Z. Effects of Congruence between Individuals’ and Hotel Commercials’ Construal Levels on Purchase Intentions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Gillis, A.J. Perception of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Gender Differences in Hong Kong Adolescent Consumers’ Green Purchasing Behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazzini, L.; Rodrigo, P.; Aiello, G.; Viglia, G. Loss or gain? The role of message framing in hotel guests’ recycling behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1944–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, E.; Kreiner, H.; McElroy, T. The effect of construal level on unethical behavior. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 157, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lermer, E.; Streicher, B.; Sachs, R.; Raue, M.; Frey, D. The effect of construal level on risk-taking. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 45, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Youn, S. Consumers as time travellers: The moderating effects of risk perception and construal level on consumers’ responses to temporal framing. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 1070–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, L.J.; Harris, P.R.; Webb, T.L. Visualizing Actions from a Third-Person Perspective: Effects on Health Behavior and the Moderating Role of Behavior Difficulty: Visualization and Perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellhas, L.; Ostafin, B.D.; Palfai, T.P.; de Jong, P.J. How to Think about Your Drink: Action-Identification and the Relation between Mindfulness and Dyscontrolled Drinking. Addict. Behav. 2016, 56, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niese, Z.A.; Eibach, R.P.; Libby, L.K. Picturing Yourself: A Social-Cognitive Process Model to Integrate Third-Person Imagery Effects. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2022, 34, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Boman, C.D.; Warner, B.R. Waiting for a Match: Mitigating Reactance in Prosocial Health Behavior Using Psychological Distance. Health Commun. 2021, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Henderson, M.D.; Eng, J.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Spatial distance and mental construal of social events. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 4, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussinson, R.; Elias, Y.; Yosef-Nitzan, E.; Mentser, S.; Zadka, M.; Weinstein, Z.; Liberman, N. Vertical Position is Associated with Construal Level and Psychological Distance. Soc. Cogn. 2021, 5, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallacher, R.R.; Wegner, D.M. What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.B.; Paulson, R.M.; Lord, C.G.; Lepper, M.R. Effects of Attitude Action Identification on Congruence between Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions toward Social Groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, J.; Mateus, R.; Silvestre, J.D.; Roders, A.P.; Bragança, L. Attitudes Matter: Measuring the Intention-Behaviour Gap in Built Heritage Conservation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.C.; Tanusia, A. Energy Conservation Behavioural Intention: Attitudes, Subjective Norm and Self-Efficacy. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 40, 012087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.R.; Zaval, L.; Weber, E.U.; Markowitz, E.M. The Influence of Anticipated Pride and Guilt on Pro-Environmental Decision Making. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Yeh, W.-J. How Does Health-Related Advertising with a Regulatory Focus and Goal Framing Affect Attitudes toward Ads and Healthy Behavior Intentions? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.J.; He, X.Y. Environmental Aesthetic Value Influences the Intention for Moral Behavior: Changes in Behavioral Moral Judgment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtveld, M.Y.; Covert, H.H.; Sherman, M.; Shankar, A.; Wickliffe, J.K.; Alcala, C.S. Advancing Environmental Health Literacy: Validated Scales of General Environmental Health and Environmental Media-Specific Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristl, A.; Kilian, S.; Mann, A. When Does a Social Norm Catch the Worm? Disentangling Social Normative Influences on Sustainable Consumption Behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Schultz, P.W. Culture and the Natural Environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sources of Variation | Maintenance Attitude | Responsibility Perception | Behavior Intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | ||

| Image reference points | (1224) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 1.207 | 0.005 |

| Text appeals | (1224) | 0.454 | 0.002 | 0.940 | 0.004 | 0.456 | 0.002 |

| Image reference points × Text appeals | (1224) | 5.216 * | 0.023 | 6.125 * | 0.021 | 4.686 * | 0.020 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, X.; Guo, Q.; Chen, M.; Lin, Y. The Construction of Image Reference Points and Text Appeals Information Tailoring in Promoting Diners’ Public Environment Maintenance Behavior Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114477

Zhu Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Du X, Guo Q, Chen M, Lin Y. The Construction of Image Reference Points and Text Appeals Information Tailoring in Promoting Diners’ Public Environment Maintenance Behavior Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114477

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yanfei, Yuli Wang, Ying Li, Xiaoxi Du, Qi Guo, Mo Chen, and Yun Lin. 2022. "The Construction of Image Reference Points and Text Appeals Information Tailoring in Promoting Diners’ Public Environment Maintenance Behavior Intention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114477

APA StyleZhu, Y., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Du, X., Guo, Q., Chen, M., & Lin, Y. (2022). The Construction of Image Reference Points and Text Appeals Information Tailoring in Promoting Diners’ Public Environment Maintenance Behavior Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114477