Acquired and Transmitted Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis among the Incarcerated Population and Its Determinants in the State of Paraná—Brazil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Location

2.2. Reference Population

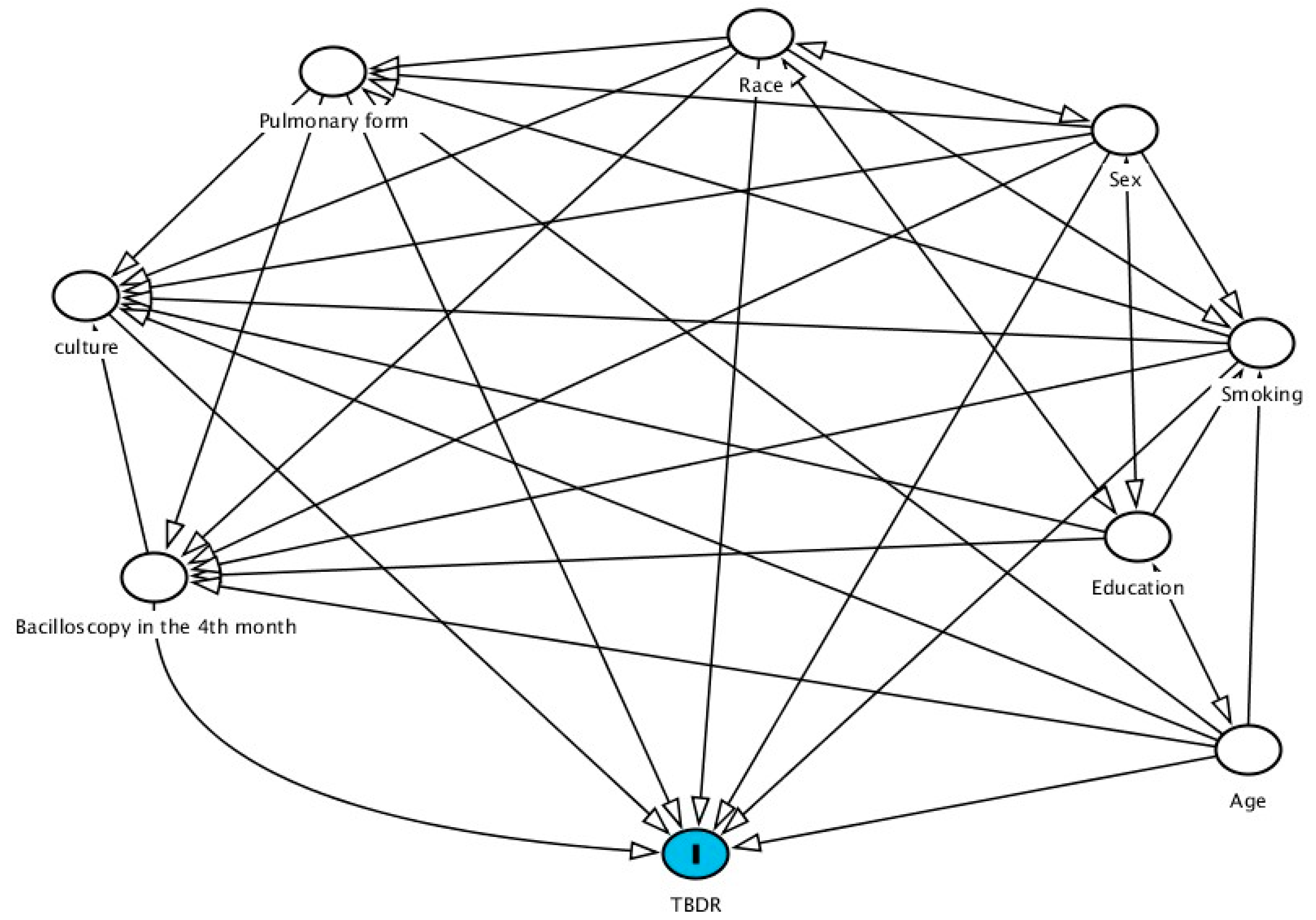

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2021 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Brazil. Health Surveillance Secretariat. Epidemiological Bulletin 2021, 22v, 52, Jun. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/boletins-epidemiologicos/2021/boletim_epidemiologico_svs_22-2.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Brazil; Health Surveillance Department; Communicable Disease Surveillance Department. Recommendations Manual for Tuberculosis Control in Brazil. 2019. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1q7t2VKo8bYFOghKQYyKMSdjcuV_CUXUz/view (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Droznin, M.; Johnson, A.; Johnson, A.M. Multidrug resistant tuberculosis in prisons located in former Soviet countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brazil; Ministry of Health; Health Surveillance Secretariat. Special Epidemiological Bulletin. v. 1, March 2020. Available online: https://antigo.saude.gov.br/boletins-epidemiologicos (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Bartholomay, P.; Pinheiro, R.S.; Johansen, F.D.C.; Oliveira, S.B.D.; Rocha, M.S.; Pelissari, D.M.; Araújo, W.N.D. Gaps in drug-resistant tuberculosis surveillance: Relating information systems in Brazil. Public Health Noteb. 2020, 36, e00082219. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.V.; Machado, M.T.C.; Dutra de Oliveira, L.G. Adherence to treatment for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (TBMDR): Case study in a reference clinic, Niterói (RJ), Brazil. Collect. Health Noteb. 2019, 27, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Savioli, M.T.G.; Morrone, N.; Santoro, I. Primary bacillary resistance in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and predictive factors associated with cure, in a reference center in the city of São Paulo. Braz. J. Pulmonol. 2019, 45, e20180075. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020: Executive Summary. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Biadglegne, F.; Rodloff, A.C.; Sack, U. Review of the prevalence and drug resistance of tuberculosis in prisons: A hidden epidemic. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 87–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, K.; Greenland, S.; Lash, T. Epidemiologia Moderna, 3rd ed.; Artmed Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Demographics of Companies 2008; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2010. Available online: http://www.ipea.gov.br/redeipea/images/pdfs/base_de_informacoess_por_setor_censitario_universo_censo_2010.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Ipardes; Paraná Institute for Economic and Social Development. Social Indicators. 2010. Available online: http://www.ipardes.gov.br/index.php?pg_conteudo=1&sistemas=1&cod_sistema=5&grupo_indic=2/ (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Dependent Penitentiary Department; Justice Ministry. Inmates in Prisons in Brazil. 2019. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZWI2MmJmMzYtODA2MC00YmZiLWI4M2ItNDU2ZmIyZjFjZGQ0IiwidCI6ImViMDkwNDIwLTQ0NGMtNDNmNy05MWYyLTRiOGRhNmJmZThlMSJ9 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Brazil. Information System for Notification of Injuries. 2021. Available online: http://portalsinan.saude.gov.br/tuberculose (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.M.; Elphick, C.S. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, Y.S.; Kamalja, K.K. Zero-inflated models and estimation in zero-inflated Poisson distribution. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. Taylor Fr. 2018, 47, 2248–2265. [Google Scholar]

- Šimundić, A.M. Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy: Vasic Definitions. EJIFCC 2009, 19, 203–211. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975285/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Di Gennaro, F.; Pizzol, D.; Onion, B.; Stubbs, B.; Monno, L.; Saracino, A.; Luchini, C.; Solmi, M.; Segafredo, G.; Putoto, G.; et al. Social determinants of therapy failure and multi drug resistance among people with tuberculosis: A review. Tuberculosis 2017, 103, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, P.V.S.; Redner, P.; Ramos, J.P. Factors associated with loss to follow-up and death in cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) treated at a reference center in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad. Public Health 2018, 34, e00048217. [Google Scholar]

- National Penitentiary Department, Brazil; Justice Ministry. National Prison Information Survey—INFOPEN—December 2017. Available online: http://antigo.depen.gov.br/DEPEN/depen/sisdepen/infopen/relatorios-sinteticos/infopen-jun-2017-rev-12072019-0721.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Valença, M.S.; Possuelo, L.G.; Cezar-Vaz, M.R.; Silva, H.D.P.E. Tuberculosis in Brazilian prisons: An integrative literature review. Sci. Public Health 2016, 21, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D.R.; Muñoz-Torrico, M.; Duarte, R.; Galvão, T.; Bonini, E.H.; Arbex, F.F.; Arbex, M.A.; Augusto, V.M.; Rabahi, M.F.; Mello, F.C.D.Q. Risk factors for tuberculosis: Diabetes, smoking, alcohol and use of other drugs. Braz. J. Pulmonol. 2018, 44, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alvarez-Corrales, N.M.; Pineda-García, L.; Carrasco Cáceres, J.A.; Aguilar Molina, P.Y. Evaluation of spoligotyping from bacilloscopies as an alternative and culture-independent methodology for the genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chil. J. Infectology 2021, 38, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostirolla, A.; Dick, C.S.; Moro, C.N.; Kipper, F.R.; Pereira, J.H.G. The failure of the prison system and human rights. Ibero-Am. J. Humanit. Sci. Educ. 2021, 1, 05–28. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, B.C.A.; Grazinoli Garrido, R. Tuberculosis in prison: A portrait of the adversities of the Brazilian prison system. Forensic Med. Costa Rica 2017, 34, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zeifert, A.P.B.; Cenci, D.R.; Manchini, A. Social justice and the 2030 agenda: Development policies for building fair and inclusive societies. Soc. Rights Public Policy Mag. 2020, 8, 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Allgayer, M.F.; Ely, K.Z.; Freitas, G.H.D.; Valim, A.R.D.M.; Gonzales, R.I.C.; Krug, S.B.F.; Possuelo, L.G. Tuberculosis: Surveillance and health care in prisons. Braz. J. Nurs. 2019, 72, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, K.M.J.D.; Villa, T.C.S.; Assolini, F.E.P.; Beraldo, A.A.; France, U.D.M.; Protti, S.T.; Palha, P.F. Delay in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in the prison system: The experience of the incarcerated patient. Text Context-Nurs. 2012, 21, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mora, F.; Sánchez-Piña, S. Nursing knowledge, practices and attitudes for the care of people with tuberculosis. Univ. Nurs. 2020, 17, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

| TBDR (n = 98) | TB- SENSITIVE (n = 555) | TOTAL (n = 653) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Age (Years old) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 64 | 65.31 | 329 | 59.28 | 393 | 60.18 |

| 30–59 | 33 | 33.67 | 220 | 39.64 | 253 | 38.74 |

| 60 or more | 1 | 1.02 | 6 | 1.08 | 7 | 1.07 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Masculine | 97 | 98.98 | 542 | 97.66 | 639 | 97.86 |

| Feminine | 1 | 1.02 | 13 | 2.34 | 14 | 2.14 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 58 | 59.18 | 380 | 68.47 | 438 | 67.08 |

| Black | 14 | 14.29 | 39 | 7.03 | 53 | 8.12 |

| Yellow | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.54 | 3 | 0.46 |

| Brown | 25 | 25.51 | 130 | 23.42 | 155 | 23.74 |

| Indigenous | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Ignored | 1 | 1.02 | 2 | 0.36 | 3 | 0.46 |

| Education | ||||||

| No education | 1 | 1.02 | 9 | 1.62 | 10 | 1.53 |

| 1st to 4th grade incomplete | 9 | 9.18 | 48 | 8.65 | 57 | 8.73 |

| 4th grade complete | 7 | 7.14 | 53 | 9.55 | 60 | 9.19 |

| 5th to 8th grade incomplete | 37 | 37.76 | 219 | 39.46 | 256 | 39.20 |

| Complete primary education | 11 | 11.22 | 64 | 11.53 | 75 | 11.49 |

| Incomplete high school | 6 | 6.12 | 51 | 9.19 | 57 | 8.73 |

| Complete high school | 4 | 4.08 | 33 | 5.95 | 37 | 5.67 |

| Incomplete higher education | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.36 | 2 | 0.31 |

| Complete higher education | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Ignored | 23 | 23.47 | 75 | 13.51 | 98 | 15.01 |

| Input Type | ||||||

| New case | 80 | 81.63 | 483 | 87.03 | 563 | 86.22 |

| Relapse | 10 | 10.20 | 41 | 7.39 | 51 | 7.81 |

| Re-entry after abandonment | 7 | 7.14 | 28 | 5.05 | 35 | 5.36 |

| Do not know | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.18 | 2 | 0.31 |

| Post-death | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.36 | 2 | 0.31 |

| Clinical Form | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 97 | 98.98 | 514 | 92.61 | 611 | 93.57 |

| Extrapulmonary | 0 | 0.00 | 24 | 4.32 | 24 | 3.68 |

| Pulmonary + Extrapulmonary | 1 | 1.02 | 17 | 3.06 | 18 | 2.76 |

| TBDR (n = 98) | TB- SENSITIVE (n = 555) | N TOTAL (n = 653) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| AIDS | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 3.06 | 32 | 5.77 | 35 | 5.36 |

| No | 86 | 87.76 | 499 | 89.91 | 585 | 89.59 |

| Ignored | 9 | 9.18 | 24 | 4.32 | 33 | 5.05 |

| Alcoholism | ||||||

| Yes | 14 | 14.29 | 71 | 12.79 | 85 | 13.02 |

| No | 74 | 75.51 | 457 | 82.34 | 531 | 81.32 |

| Ignored | 10 | 10.20 | 27 | 4.86 | 37 | 5.67 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1.02 | 9 | 1.62 | 10 | 1.53 |

| No | 88 | 89.80 | 518 | 93.33 | 606 | 92.80 |

| Ignored | 9 | 9.18 | 28 | 5.05 | 37 | 5.67 |

| Mental disease | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1.02 | 5 | 0.90 | 6 | 0.92 |

| No | 88 | 89.80 | 524 | 94.41 | 612 | 93.72 |

| Ignored | 9 | 9.18 | 26 | 4.68 | 35 | 5.36 |

| Illicit drugs | ||||||

| Yes | 40 | 40.82 | 279 | 50.27 | 319 | 48.85 |

| No | 38 | 38.78 | 266 | 47.93 | 304 | 46.55 |

| Ignored | 20 | 20.41 | 10 | 1.80 | 30 | 4.59 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 43 | 43.88 | 285 | 51.35 | 328 | 50.23 |

| No | 37 | 37.76 | 263 | 47.39 | 300 | 45.94 |

| Ignored | 18 | 18.37 | 7 | 1.26 | 25 | 3.83 |

| X-ray | ||||||

| Suspect | 70 | 71.43 | 434 | 78.20 | 504 | 77.18 |

| Normal | 3 | 3.06 | 11 | 1.98 | 14 | 2.15 |

| Unrealized | 25 | 25.51 | 109 | 19.64 | 134 | 20.52 |

| Ignored | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Sputum Culture | ||||||

| Positive | 84 | 85.71 | 372 | 67.03 | 456 | 69.83 |

| Negative | 5 | 5.10 | 85 | 15.31 | 90 | 13.78 |

| In progress | 3 | 3.06 | 12 | 2.16 | 15 | 2.30 |

| Not performed | 6 | 6.11 | 86 | 15.50 | 92 | 14.09 |

| HIV | ||||||

| Positive | 3 | 3.06 | 32 | 5.77 | 35 | 5.36 |

| Negative | 93 | 94.90 | 485 | 87.38 | 578 | 88.52 |

| In progress | 1 | 1.02 | 3 | 0.54 | 4 | 0.61 |

| Not performed | 1 | 1.02 | 35 | 6.30 | 36 | 5.52 |

| Histopathology | ||||||

| Alcohol-Acid Resistant Bacilli Positive | 3 | 3.06 | 23 | 4.14 | 26 | 3.98 |

| Suggestive of TB | 2 | 2.04 | 14 | 2.52 | 16 | 2.45 |

| Not suggestive of TB | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.15 |

| In progress | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.72 | 4 | 0.61 |

| Unrealized | 89 | 90.82 | 505 | 90.99 | 594 | 90.96 |

| Ignored | 4 | 4.08 | 8 | 1.44 | 12 | 1.84 |

| Immigrant | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.54 | 3 | 0.46 |

| No | 81 | 82.65 | 550 | 99.10 | 631 | 96.63 |

| Ignored | 17 | 17.35 | 2 | 0.36 | 19 | 2.91 |

| Receive government benefit | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1.02 | 10 | 1.80 | 11 | 1.68 |

| No | 75 | 76.53 | 525 | 94.59 | 598 | 91.58 |

| Ignored | 22 | 22.45 | 20 | 3.60 | 44 | 6.74 |

| Rapid molecular test | ||||||

| Sensitive to Rifampicin | 43 | 43.88 | 428 | 77.12 | 471 | 72.13 |

| Resistant to Rifampicin | 18 | 18.37 | 6 | 1.08 | 24 | 3.68 |

| Undetectable | 1 | 1.02 | 47 | 8.47 | 48 | 7.35 |

| Ignored | 22 | 20.41 | 20 | 3.60 | 44 | 6.74 |

| Unrealized | 16 | 16.33 | 1 | 0.18 | 17 | 2.60 |

| Sensitivity test | ||||||

| Resistant to Isoniazid only | 53 | 54.08 | 32 | 5.77 | 85 | 13.02 |

| Resistant only to Rifampicin | 3 | 3.06 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.46 |

| Resistant to Isoniazid and Rifampicin | 4 | 4.08 | 1 | 0.18 | 5 | 0.77 |

| Resistant to other first-line drugs | 5 | 5.10 | 2 | 0.36 | 7 | 1.07 |

| Sensitive | 8 | 8.16 | 304 | 54.77 | 312 | 47.78 |

| In progress | 0 | 0.00 | 10 | 1.80 | 10 | 1.53 |

| Unrealized | 5 | 5.10 | 55 | 9.91 | 60 | 9.19 |

| Ignored | 20 | 20.41 | 151 | 27.21 | 171 | 26.19 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | ||||||

| Positive | 1 | 1.02 | 28 | 5.05 | 29 | 4.44 |

| Negative | 93 | 94.90 | 493 | 88.83 | 586 | 89.74 |

| Ignored | 4 | 4.08 | 34 | 6.13 | 38 | 5.82 |

| Transfer | ||||||

| Different state | 2 | 2.04 | 10 | 1.80 | 12 | 1.84 |

| Coefficient | Pr (>|z|) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education: 8 to 11 years of study | −0.87 | 0.04 | 0.41 (0.16–0.93) |

| Clinical form: Pulmonary | 2.28 | 0.05 | 9.87 (1.55–23.81) |

| Not use of tobacco | −3.84 | <0.01 | 0.02 (0.01–0.06) |

| Negative sputum culture | −1.20 | 0.01 | 0.29 (0.09–0.74) |

| Positive bacilloscopy in the 4th month of treatment | 1.86 | 0.05 | 6.45 (1.04–53.79) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, M.S.d.; Pieri, F.M.; Berra, T.Z.; Scholze, A.R.; Ramos, A.C.V.; de Almeida Crispim, J.; Giacomet, C.L.; Alves, Y.M.; da Costa, F.B.P.; Moura, H.S.D.; et al. Acquired and Transmitted Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis among the Incarcerated Population and Its Determinants in the State of Paraná—Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214895

Santos MSd, Pieri FM, Berra TZ, Scholze AR, Ramos ACV, de Almeida Crispim J, Giacomet CL, Alves YM, da Costa FBP, Moura HSD, et al. Acquired and Transmitted Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis among the Incarcerated Population and Its Determinants in the State of Paraná—Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214895

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Márcio Souza dos, Flávia Meneguetti Pieri, Thaís Zamboni Berra, Alessandro Rolim Scholze, Antônio Carlos Vieira Ramos, Juliane de Almeida Crispim, Clóvis Luciano Giacomet, Yan Mathias Alves, Fernanda Bruzadelli Paulino da Costa, Heriederson Sávio Dias Moura, and et al. 2022. "Acquired and Transmitted Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis among the Incarcerated Population and Its Determinants in the State of Paraná—Brazil" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214895