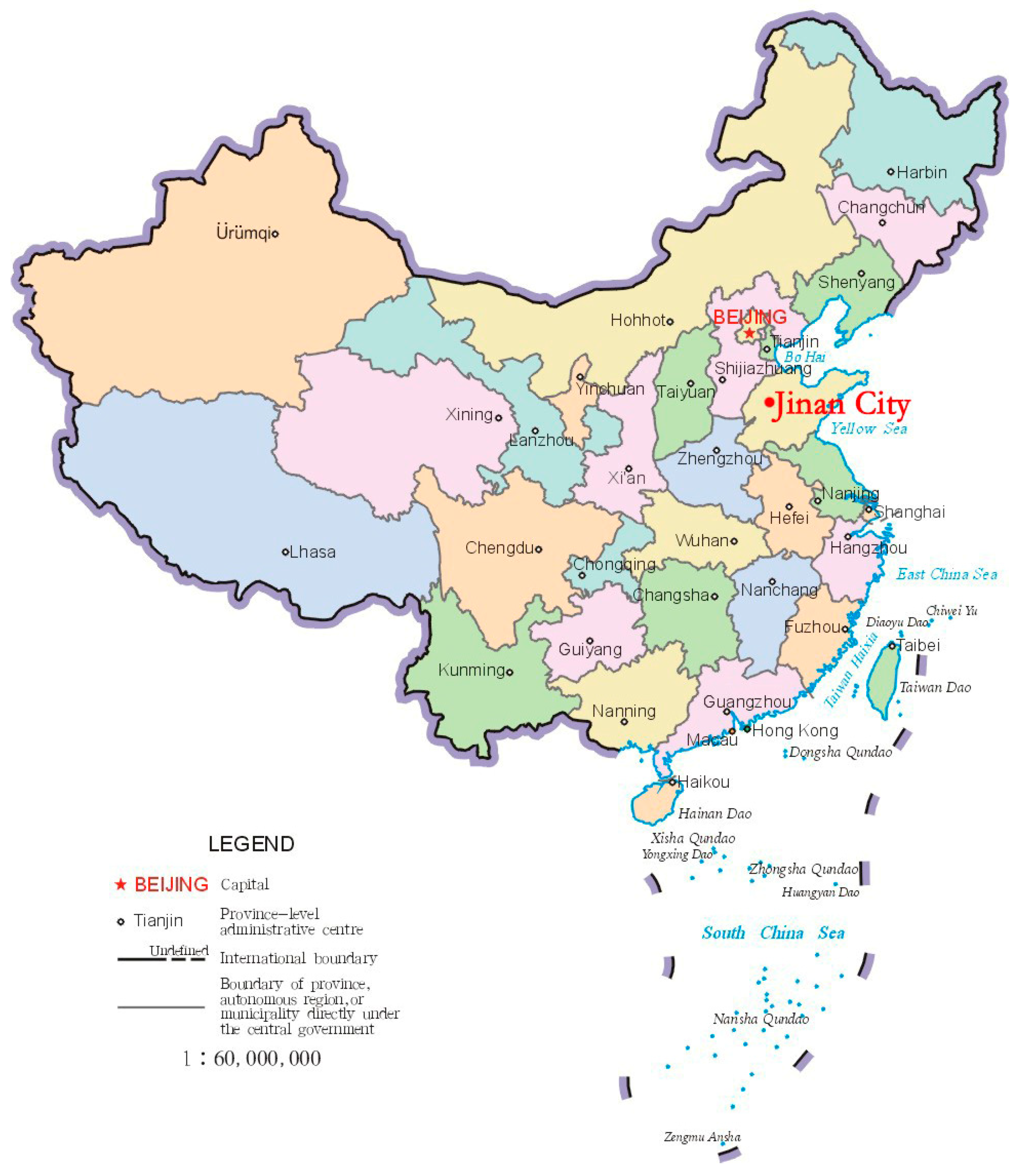

Investigating the Usage Patterns of Park Visitors and Their Driving Factors to Improve Urban Community Parks in China: Taking Jinan City as an Example

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Site

2.3. Sample Selection and Design

2.4. Survey Instruments and Procedures

2.5. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Who Uses Community Parks in Jinan City?

Demographic Data

3.2. How Are the Community Parks Used?

3.2.1. Visitor Usage Patterns

“My grandson went to primary school last year, and now I don’t have to look after him all day. So, I go to Shunyu Park, which is close to home and convenient every day, play chess, Tai Chi, and chat with my friends to enjoy time.”

“My husband usually drives the family to the zoo or botanical garden outside the city on weekends, but during the week I simply walk with my son to Lingxiu Park for him to socialize and experience nature. This is really convenient.”

“I prefer to lie down and play the mobile phone or computer games with my friends during my rest time. But since I was diagnosed with moderate fatty liver disease in my physical examination last week, I have decided to run in Tangye Park for an hour after work from now on.”

“I prefer to pass through Luneng No. 7 Park on the way home from the bus station. Compared with the street sidewalk, the park road is quieter and safer during rush hours, without noise and cars.”

“I go to Huangtai Park with five or six neighbors every night to dance regularly. The park is near my home, convenient, safe and enjoyable. Now our dancing team has grown to about 20 people, the dynamic music attracting many youthful people to join us in square dancing.”

3.2.2. Motives for Visiting

“I used to play in the mall with friends, but now we also choose to go to a nearby community park to enjoy nature and take a fresh breath, which makes us cheerful; after all, we always stay inside day and night.”

3.3. What Are the Visitors’ Desired Improvements to the Community Parks in Jinan?

Desired Improvements

“Community parks are usually crowded with elderly people and children, who are more likely to have accidents, thus, the friendliness of the park is very important. It would be better if emergency equipment were installed in the park’s activity areas.”

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Revision of World Urbanization Prospects 2018. Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Imam, A.U.K.; Banerjee, U.K. Urbanisation and greening of Indian cities: Problems, practices, and policies. Ambio 2016, 45, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Quaas, M.F.; Smulders, S. Brown growth, green growth, and the efficiency of urbanization. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 71, 529–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.; Song, K.; Kim, G.; Chon, J. Flood-adaptive green infrastructure planning for urban resilience. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 17, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olic, P.; Stober, D. Urban green infrastructure for shrinking city: Case study—City of Osijek. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Multidisciplinary Civil Engineering, Architecture, Urban Planning Symposium (WMCAUS), Prague, Czech Republic, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D.; Zuñiga, M.E. Put a park on it: How freeway caps are reconnecting and greening divided cities. Cities 2019, 85, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myungshik, C.; Kim, H.W. Identifying priority management area for unexecuted urban parks in long-term by considering the pattern of green infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 243–265. [Google Scholar]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Evidence for designing health promoting pocket parks. Int. J. Archit. Res. Archnet-Ijar 2014, 8, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Standard for Classification of Urban Green Space, Industry Standard–Urban Construction. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Carlson, S.A.; Brooks, J.D.; Brown, D.R.; Buchner, D.M. Racial/ethnic differences in perceived access, environmental barriers to use, and use of community parks. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A49. [Google Scholar]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basu, S.; Nagendra, H. Perceptions of park visitors on access to urban parks and benefits of green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, F.; Nygaard, A.; Stone, W.M.; Levin, I. Green gentrification or gentrified greening: Metropolitan Melbourne. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Wang, X.J. Progress and gaps in research on urban green space morphology: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmayr, D.; Friedman, H.S. Cultivating healthy trajectories: An experimental study of community gardening and health. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.A. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 001–018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zube, H.E.; Moore, G.T. (Eds.) Advances in Environment, Behavior, Design Volume 1; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; He, P. MSPA-based urban green infrastructure planning and management approach for urban sustainability: Case study of Longgang in China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, A5014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.B.; Haberman, C.P.; Groff, E.R. Urban park crime: Neighborhood context and park features. J. Crim. Justice 2019, 64, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Denniss, E.; Ball, K.; Koorts, H.; Deforche, B.; Timperio, A. Increasing translation of research evidence for optimal park design: A qualitative study with stakeholders. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duan, Y.P.; Wagner, P.; Zhang, R.; Wulff, H.; Brehm, W. Physical activity areas in urban parks and their use by the elderly from two cities in China and Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Miller, P.A. The impact of green infrastructure on human health and well-being: The example of the huckleberry Trail and the Heritage Community Park and Natural Area in Blacksburg, Virginia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Fan, S.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Xie, Y.; Dong, L. Large urban parks summertime cool and wet island intensity and its influencing factors in Beijing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.W.; Chao, J.C. Study on the value model of urban green infrastructure development—A case study of the central district of Taichung city. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Almanza, E.; Jerrett, M.; Wolch, J.; Pentz, M.A. Neighborhood park use by children: Use of accelerometry and global positioning systems. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anguluri, R.N.; Narayanan, P. Role of green space in urban planning: Outlook towards smart cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuvonen, M.; Sievänen, T.; Tönnes, S.; Koskela, T. Access to green areas and the frequency of visits—A case study in Helsinki. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T.; Butt, I.; Peh, K.S.H. The importance of green spaces to public health: A multi-continental analysis. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choumert, J. An empirical investigation of public choices for green spaces. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, R.; Meadows, M.E.; Sen Gupta, D.; Xu, D. Changing urban green spaces in Shanghai: Trends, drivers and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.X.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. The relationships between urban parks, residents’ physical activity, and mental health benefits: A case study from Beijing, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 190, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, D.S.; Rigolon, A.; Schmalz, D.L.; Brown, B.B. Policy and environmental predictors of park visits during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Getting out while staying in. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.C.; Innes, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on urban park visitation: A global analysis. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.C.L. Park user preferences for establishing a sustainable forest park in Taipei, Taiwan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.S.; Lin, C.T. Preliminary study of the influence of the spatial arrangement of urban parks on local temperature reduction. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Kang, N.; Yang, X.; Xia, Y. Impact of perception of green space for health promotion on willingness to use parks and actual use among young urban residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Li, Q.; Chand, S. Factors influencing residents’ access to and use of country parks in Shanghai, China. Cities 2020, 97, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinew, K.J.; Stodolska, M.; Floyd, M.; Hibbler, D.; Allison, M.; Johnson, C.; Santos, C. Race and ethnicity in leisure behavior: Where have we been and where do we need to go? Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Ostby, K. Pocket parks for people—A study of park design and use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balai Kerishnan, P.B.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Maulan, S. Investigating the usability pattern and constraints of pocket parks in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 50, 126647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, P.K.; Smith, W.R.; Moore, R.C.; Floyd, M.F.; Bocarro, J.N.; Cosco, N.G.; Danninger, T.M. Park Use among Youth and Adults: Examination of Individual, Social, and Urban Form Factors. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 768–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J. Research on the relationship between green growth and urbanization efficiency. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2021, 30, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Nordh, H.; Hartig, T.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Fry, G.L. Components of small urban parks that predict the possibility for restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Marsh, T.; Williamson, S.; Han, B.; Derose, K.P.; Golinelli, D.; McKenzie, T.L. The Potential for Pocket Parks to Increase Physical Activity. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Schipperjin, J.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Use of small public urban green spaces (SPUGS). Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.P.; Zhang, C.Z. Why public-private cooperation is not prevalent in national parks within centralised countries. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1109–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.J.; Xie, J.; Jennings, G. Health, identification and pleasure: An ethnographic study on the self-management and construction of Taijiquan Park culture space. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgüner, H. Cultural differences in attitudes towards urban parks and green spaces. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.; Baur, J.W.R.; Hill, E.; Georgiev, S. Urban parks and psychological sense of community. J. Leis. Res. 2015, 47, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Rhodes, J.; Dade, M. An evaluation of participatory mapping methods to assess urban park benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Department of Statistics Jinan City Demographic Statistics: Jinan Seventh National Population Census Bulletin. Available online: http://jntj.jinan.gov.cn (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Jasmani, Z.; Ravn, H.P.; van den Bosch, C.C.K. The influence of small urban parks characteristics on bird diversity: A case study of Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strum, R.; Cohen, D. Proximity to urban parks and mental health. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2014, 17, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Menec, V.H.; Brown, C.L.; Newall, N.E.; Nowicki, S. How important is having amenities within walking distance to middle-aged and older adults, and does the perceived importance relate to walking? J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 546–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Christian, H.; Carver, A.; Salmon, J. Physical activity benefits from taking your dog to the park. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 185, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.C.; Li, D.Y. Metric or topological proximity? The associations among proximity to parks, the frequency of residents’ visits to parks, and perceived stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.Y.; Huang, G.; Wu, J.; Guo, X. How do travel distance and park size influence urban park visits? Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 52, 126689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A. Parks and young people: An environmental justice study of park proximity, acreage, and quality in Denver, Colorado. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Vu, H.Q.; Li, G.; Law, R. Topic modelling for theme park online reviews: Analysis of Disneyland. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Pearce, J.; Mitchell, R.; Day, P.; Kingham, S. The association between green space and cause-specific mortality in urban New Zealand: An ecological analysis of green space utility. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madureira, H.; Nunes, F.; Oliveira, J.V.; Cormier, L.; Madureira, T. Urban residents’ beliefs concerning green space benefits in four cities in France and Portugal. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Brand behavioral intentions of a theme park in China: An application of brand experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanas, E. Experiencing designs and designing experiences: Emotions and theme parks from a symbolic interactionist perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, S. Mechanisms underlying the effects of landscape features of urban community parks on health-related feelings of users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.; Ahmad, A.; Paul, A.; Rho, S. Urban planning and building smart cities based on the Internet of Things using Big Data analytics. Comput. Netw. 2016, 101, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Veitch, J.; Rodwell, L.; Abbott, G.; Carver, A.; Flowers, E.; Crawford, D. Are park availability and satisfaction with neighbourhood parks associated with physical activity and time spent outdoors? BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B.E.; Buijs, A. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cengiz, C.; Cengiz, B.; Bekci, B. Environmental quality analysis for sustainable urban public green spaces management in Bartm, Turkey. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 10, 938–946. [Google Scholar]

- Sanesi, G.; Chiarello, F. Residents and urban green spaces: The case of Bari. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Urban form and context: Cultural differentiation in the uses of urban parks. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1995, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.; Harrison, C.M.; Limb, M. People, parks and the urban green: A study of popular meanings and values for open spaces in the city. Urban Stud. 1988, 25, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; Hartig, T. Alone or with a friend: A social context for psychological restoration and environmental preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Naghten, P.; Urry, J. Bodies in the woods. Body Soc. 2000, 6, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreetheran, M.; van den Bosch, C.C.K. A socio-ecological exploration of fear of crime in urban green spaces—A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F. Greener urbanization? Changing accessibility to parks in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumoto, S.; Jones, A.; Shimizu, C. Longitudinal trends in equity of park accessibility in Yokohama, Japan: An investigation into the role of causal mechanisms. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2014, 46, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonti, N.F.; Campbell, L.K.; Svendsen, E.S.; Johnson, M.L.; Novem Auyeung, D.S. Fear and fascination: Use and perceptions of New York City’s forests, wetlands, and landscaped park areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qi, X. Protest response and contingent valuation of an urban forest park in Fuzhou city, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Public Security Urban People’s Police Patrol Regulations. Available online: https://app.mps.gov.cn (accessed on 24 February 1994).

- Van Hecke, L.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Clarys, P.; Van Dyck, D.; Veitch, J.; Deforche, B. Active Use of Parks in Flanders (Belgium): An Exploratory Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, H.; Pain, R. Revisiting fear and place: Women’s fear of attack and the built environment. Geoforum 2000, 31, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruize, H.; van der Vliet, N.; Staatsen, B.; Bell, R.; Chiabai, A.; Muiños, G.; Higgins, S.; Quiroga, S.; Martinez-Juarez, P.; Aberg Yngwe, M.; et al. Urban Green Space: Creating a Triple Win for Environmental Sustainability, Health, and Health Equity through Behavior Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward-Thompson, C.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, W.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Tao, J.; Wu, L.; Xu, S.; Kang, Y.; Zeng, Q. The effect of green space behaviour and per capita area in small urban green spaces on psychophysiological responses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 192, 103637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, L.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Orsega-Smith, E. An Examination of park preferences and behaviors among urban residents: The role of residential location, race, and age. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, F.W.; Petersen, A.H.; Strange, N.; Lund, M.P.; Rahbek, C.A. Quantitative analysis of biodiversity and the recreational value of potential national parks in Denmark. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawan, M.; Lowe, C.; Sundjaya; Hutabarat, C.; Black, A. Co-management and the creation of national parks in Indonesia: Positive lessons learned from the Togean Islands National Park. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 1183–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, T.; Banpot, S.; Padungpong, C.; Bidayabha, T. Records of Spotted Linsang Prionodon pardicolor from Thap Lan and Pang Sida National Parks, Thailand. Small Carniv. Conserv. 2011, 44, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vierikko, K.; Gonçalves, P.; Haase, D.; Elands, B.; Ioja, C.; Jaatsi, M.; Pieniniemi, M.; Lindgren, J.; Grilo, F.; Santos-Reis, M.; et al. Biocultural diversity (BCD) in European cities—Interactions between motivations, experiences and environment in public parks. Urban For. Urban Green 2020, 48, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Vogelsong, H.; Green, G.; Cordell, K. Outdoor Recreation Participation of People with Mobility Disabilities: Selected Results of the National Survey of Recreation and the Environment. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2004, 22, 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, P.; Weijs-Perrée, M.; Dane, G.; van Vliet, E.; Liu, H.; Sun, S.; Borgers, A. A Comparative Study of Urban Park Preferences in China and The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, K.T.; Sharma, T.; Steinberg, A.; Hodges-Copple, S.; Jacobson, E.; Matveeva, L. More inclusive parks planning: Park quality and preferences for park access and amenities. Environ. Justice 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, P.; Arlinghaus, R. Benefits and constraints of outdoor recreation for people with physical disabilities: Inferences from recreational fishing. Leis. Sci. 2009, 32, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Community Park Real Photos | Community Park Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Name: Kuangshan park Size: 6.9 hm2 District: Huaiyin district Street name: Jiqing Street GPS location: E 116.954878° N 36.691597° |

| 2 |  | Name: Huapu park Size: 5.8 hm2 District: Huaiyin district Street name: Jingshi Street GPS location: E 116.949529° N 36.659509° |

| 3 |  | Name: Huangtai park Size: 4.7 hm2 District: Tianqiao district Street name: Hangyun Street GPS location: E 117.055937° N 36.711579° |

| 4 |  | Name: Yingxiong park Size: 7.2 hm2 District: Shizhong district Street name: Yingxiongshan Street GPS location: E 117.010969° N 36.645278° |

| 5 |  | Name: Zhongshan park Size: 6.3 hm2 District: Shizhong district Street name: Jingsan street GPS location: E 116.995771° N 36.667601° |

| 6 |  | Name: Shunyun park Size: 4.5 hm2 District: Shizhong district Street name: Shunyu Street GPS location: E 117.022598° N 36.633229° |

| 7 |  | Name: Lingxiu park Size: 4.1 hm2 District: Shizhong district Street name: Jianxiu Street GPS location: E 117.009673° N 36.597034° |

| 8 |  | Name: Yanzishan park Size: 4.2 hm2 District:Lixia district Street name: Peace Street GPS location: E 117.06713° N 36.663794° |

| 9 |  | Name: Quancheng park Size: 7.1 hm2 District: Lixia district Street name: Jingshi Street GPS location: E 117.026361° N 36.651235° |

| 10 |  | Name: Huancheng park Size: 6.4 hm2 District: Lixia district Street name: Jiefang Street GPS location: E 117.038033° N 36.668754° |

| 11 |  | Name: Baihua park Size: 6.9 hm2 District: Licheng district Street name: Minziqian stret GPS location: E 117.07713° N 36.681782° |

| 12 |  | Name: Huanxiang park Size:4.5 hm2 District: Licheng district Street name: Huanxiangdian Street GPS location: E 117.083152° N 36.719796° |

| 13 |  | Name: Luneng park Size: 5.3 hm2 District: Licheng district Street name: Shiji Street GPS location: E 117.21927° N 36.698993° |

| 14 |  | Name: Tangye park Size: 6.5 hm2 District: Licheng district Street name: Tangye East street GPS location: E 117.235363° N 36.686717° |

| Respondent Information | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Sex? | ||

| Male | 264 | 48.7 |

| Female | 278 | 51.3 |

| Race? | ||

| Han nationality | 510 | 94.1 |

| Hui nationality | 32 | 5.9 |

| Age group? | ||

| Under 10 years | 128 | 23.6 |

| 10–20 years | 68 | 12.5 |

| 20–40 years | 56 | 10.3 |

| 40–55 years | 102 | 18.8 |

| Over 55 years | 188 | 34.7 |

| Occupation? | ||

| Children (≤6 years) | 101 | 18.6 |

| Student | 66 | 12.2 |

| Public sector | 64 | 11.8 |

| Private sector employees | 44 | 8.1 |

| Self-employed | 29 | 5.4 |

| Pensioner | 212 | 39.1 |

| Unemployed | 26 | 4.8 |

| The Usage Pattern of Visitor | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Would you like to visit this community park alone or in a group? | ||

| Alone | 198 | 36.5 |

| In a group | 344 | 63.5 |

| If in a group, with whom? | ||

| Friends | 358 | 66.1 |

| Family members | 176 | 32.5 |

| Others | 8 | 1.4 |

| How often do you visit this community park? | ||

| ≥1 a day | 192 | 35.4 |

| 3–4 times a week | 128 | 23.6 |

| 1–2 times a week | 92 | 17.0 |

| 1–2 times a month | 66 | 12.2 |

| 1–2 times a year | 64 | 11.8 |

| How did you get to the park? | ||

| Walk | 283 | 52.2 |

| Bicycle/E-bike | 168 | 31.0 |

| Public transport (bus, subway) | 76 | 14.0 |

| Car | 12 | 2.2 |

| Taxi | 3 | 0.6 |

| How long is the road travel time? | ||

| ≤5 min | 48 | 8.9 |

| 5–10 min | 180 | 33.2 |

| 10–20 min | 242 | 44.6 |

| 20–30 min | 56 | 10.3 |

| ≥30 min | 16 | 3.0 |

| When would you like to come to this community park? | ||

| Weekdays | 273 | 50.4 |

| Weekends | 169 | 31.2 |

| Public holiday | 74 | 13.7 |

| Special event | 26 | 4.7 |

| What time would you like to visit this community park? | ||

| 6:00–9:00 am | 89 | 16.4 |

| 9:00–12:00 am | 125 | 23.1 |

| 2:00–6:00 pm | 223 | 41.1 |

| 7:00–9:00 pm | 105 | 19.4 |

| How long do you normally stay at the park? | ||

| ≤30 min | 51 | 9.4 |

| 30 min–1 h | 217 | 40.0 |

| 1–2 h | 254 | 46.9 |

| ≥2 h | 20 | 3.7 |

| Park Desired Improvements | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Are you satisfied with the community park? | ||

| Very satisfied | 45 | 8.3 |

| Satisfactory, fewer improvements are needed | 356 | 65.7 |

| Unsatisfactory, more improvements are needed | 129 | 23.8 |

| Very unsatisfactory | 12 | 2.2 |

| What is the main desired improvement of you to the community park? | ||

| No changes | 32 | 5.9 |

| Landscape viewpoints | 18 | 3.3 |

| Art sculptures | 21 | 3.9 |

| Vegetation | 45 | 8.3 |

| Unfavorable visitor behaviors | 13 | 2.4 |

| Park cleanliness | 24 | 4.4 |

| Add recycling bins | 8 | 1.5 |

| Add bathroom | 23 | 4.2 |

| Add concession stands | 15 | 2.8 |

| Lighting | 35 | 6.5 |

| Emergency buttons | 41 | 7.6 |

| Information/interpretive signs | 17 | 3.1 |

| Level off the road | 13 | 2.4 |

| Wheelchair accessibility | 27 | 5.0 |

| Add rest seats | 34 | 6.3 |

| Add activity area | 41 | 7.6 |

| Add activity facilities for children | 37 | 6.8 |

| Add physical training facilities | 72 | 13.3 |

| Add dog/pet activity area | 26 | 4.8 |

| Would you like to use community parks more often if changes were implemented? | ||

| Yes | 433 | 79.9 |

| Maybe | 64 | 11.8 |

| No | 23 | 4.2 |

| No response | 22 | 4.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, D.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Fei, X. Investigating the Usage Patterns of Park Visitors and Their Driving Factors to Improve Urban Community Parks in China: Taking Jinan City as an Example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315504

Kong D, Chen Z, Li C, Fei X. Investigating the Usage Patterns of Park Visitors and Their Driving Factors to Improve Urban Community Parks in China: Taking Jinan City as an Example. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315504

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Deyi, Zujian Chen, Cheng Li, and Xinhui Fei. 2022. "Investigating the Usage Patterns of Park Visitors and Their Driving Factors to Improve Urban Community Parks in China: Taking Jinan City as an Example" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315504

APA StyleKong, D., Chen, Z., Li, C., & Fei, X. (2022). Investigating the Usage Patterns of Park Visitors and Their Driving Factors to Improve Urban Community Parks in China: Taking Jinan City as an Example. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315504