COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among U.S. Veterans Experiencing Homelessness in Transitional Housing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment & Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. GPD Sites

3. Results

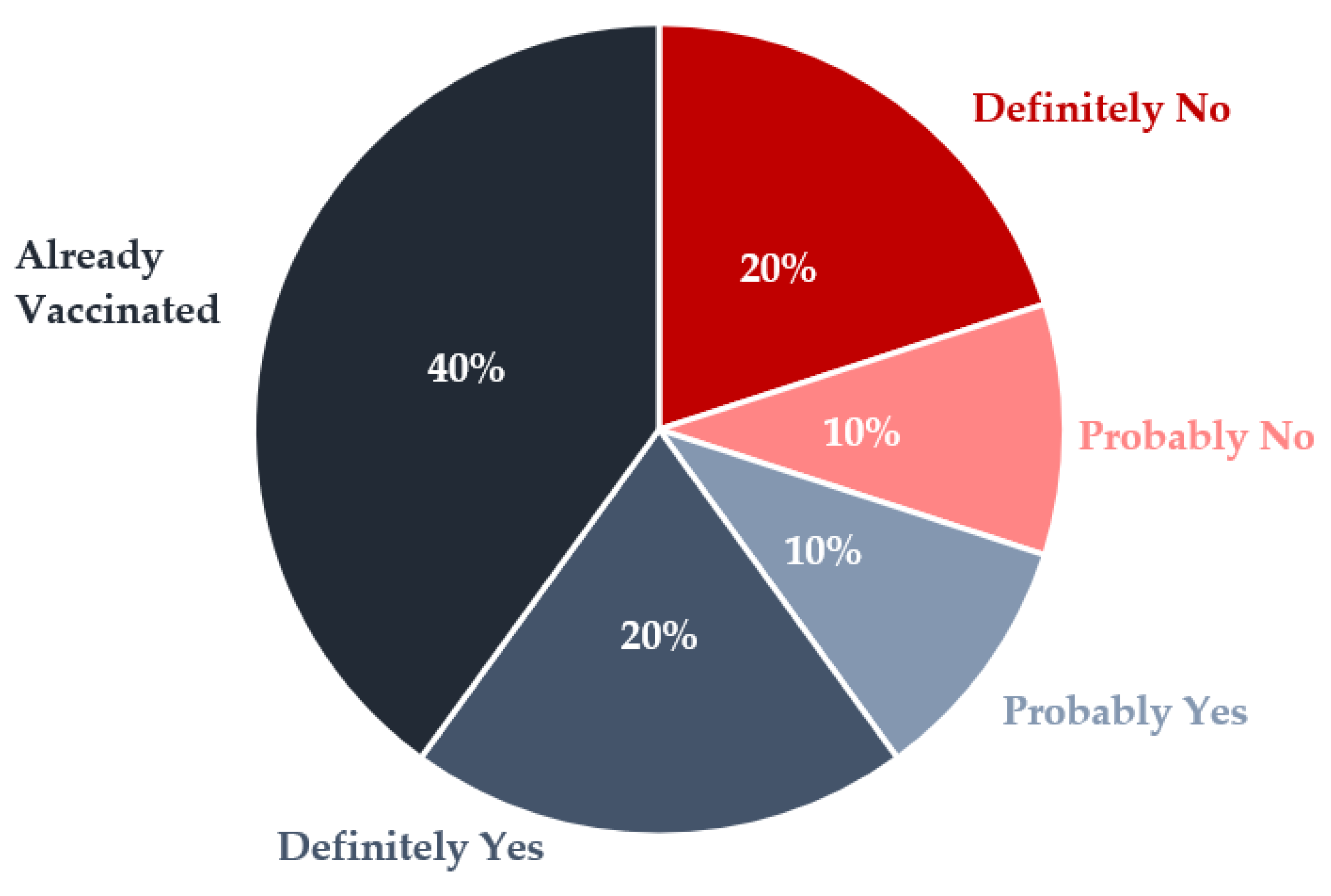

3.1. COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake Attitudes, Behaviors, Barriers, and Facilitators

“My first wife died from [COVID-19] and thousands of Americans are dying from it. I got the shot, I got PTSD, and it gave me some nightmares… I had flashbacks of being in the jungle again… I’m still going to get the second shot though, because… through time, I’ll be pretty much protected from it.”(Iowa2)

“They rushed this in like seven, eight months, so they can’t tell you what it’s going to be like in two years, five years. You know, back when the smallpox [vaccine] first came out, they said—‘Oh, that was fine.’ Then they started having birth defects and you know, like different problems with that, you know what I mean?… You can’t tell me what it’s going to be like five years down the road, just to be safe today. I don’t want to get cancer five years down the road, so I didn’t get COVID today.”(Florida2)

“If someone wants to give it to me, I would absolutely, 100% take it. No issues, whatsoever. But… it’s such a low priority, I’m not generally going to seek it out.”(Iowa1)

3.2. Military Experience

“They said you can get a vaccine today, and I said okay… When somebody offers me a vaccine, I’m like all right I’ll get it. I’m prepared… I’m used to being a guinea pig… I was in the Army active for three and a half years, and then I did nine and a half years total, the reserve and active. So, you know people sticking needles in me, telling me, ‘all right you need to take this’, and I’m like ‘okay’.”(Massachusetts4)

“Going into the military, I had tons of vaccines, and putting one more in my body is something I try not to do if I don’t have to.”(California2)

3.3. Influenza Vaccine Uptake

3.4. Sources of Information

“The most reliable source of information about COVID is direct word of mouth from someone who has had it.”(Kentucky2)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, R.; Li, G.M. Hesitancy in the time of coronavirus: Temporal, spatial, and sociodemographic variations in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollalo, A.; Tatar, M. Spatial Modeling of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talafha, Q.M.; Al-Haidose, A.; AlSamman, A.Y.; Abdallah, S.A.; Istaiteyeh, R.; Ibrahim, W.N.; Hatmal, M.M.; Abdallah, A.M. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Vulnerable Groups: Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.S.; Ho, M.M.; Kiss, A.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Hwang, S.W. Homelessness and the Response to Emerging Infectious Disease Outbreaks: Lessons from SARS. J. Hered. 2008, 85, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Wilson, M. COVID-19: A potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e186–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoella, C.; Ralli, M.; Maggiolini, A.; Arcangeli, A.; Ercoli, L. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among persons experiencing homelessness in the City of Rome, Italy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 3132–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Longchamps, C.; Ducarroz, S.; Crouzet, L.; Vignier, N.; Pourtau, L.; Allaire, C.; Colleville, A.; El Aarbaoui, T.; Melchior, M.; ECHO Study Group. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among persons living in homeless shelters in France. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3315–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidance for Health Departments: COVID-19 Vaccination Implemen-tation for People Experiencing Homelessness. 30 April 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-shelters/vaccination-guidance.html (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Pham, O.; Rudowitz, R.; Tolbert, J. Risks and Vaccine Access for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness: Key Issues to Con-Sider. 24 March 2021. Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/covid-19-risks-vaccine-access-individuals-experiencing-homelessness-key-issues/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Van Ness, L. States Fail to Prioritize Homeless People for Vaccines. Stateline. 1 March 2021. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/03/01/states-fail-to-prioritize-homeless-people-for-vaccines (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Hamel, L.; Lopes, L.; Kirzinger, A.; Sparks, G.; Stokes, M.; Brodle, M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Media and Misinfor-Mation; Kaiser Family Foundation. 8 November 2021. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-media-and-misinformation/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Knight, K.R.; Duke, M.R.; Carey, C.A.; Pruss, G.; Garcia, C.M.; Lightfoot, M.; Imbert, E.; Kushel, M. COVID-19 Testing and Vaccine Acceptability Among Homeless-Experienced Adults: Qualitative Data from Two Samples. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 37, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Liu, M.; Jenkinson, J.I.R.; Nisenbaum, R.; Brown, M.; Pedersen, C.; Hwang, S.W. COVID-19 Vaccine Coverage and Sociodemographic, Behavioural and Housing Factors Associated with Vaccination among People Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto, Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balut, M.D.; Chu, K.; Gin, J.L.; Dobalian, A.; Der-Martirosian, C. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccination among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, A.A.; Yeh, M.; Gardner, A.; DeFoe, T.L.; Garcia, A.; Kelen, P.V.; Montgomery, M.P.; Tippins, A.E.; Carmichael, A.E.; Gibbs, C.R.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptability Among Clients and Staff of Homeless Shelters in Detroit, Michigan, February 2021. Health Promot. Pr. 2021, 23, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.P.; Meehan, A.A.; Cooper, A.; Toews, K.-A.; Ghinai, I.; Schroeter, M.K.; Gibbs, R.; Rehman, N.; Stylianou, K.S.; Yeh, D.; et al. Notes from the Field: COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness—Six U.S. Jurisdictions, December 2020–August 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1676–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.H.; Cox, S.N.; Hughes, J.P.; Link, A.C.; Chow, E.J.; Fosse, I.; Lukoff, M.; Shim, M.M.; Uyeki, T.M.; Ogokeh, C.; et al. Trends in COVID-19 vaccination intent and factors associated with deliberation and reluctance among adult homeless shelter residents and staff, 1 November 2020 to 28 February 2021—King County, Washington. Vaccine 2021, 40, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, S.Z.; Richard, L.; Hwang, S.W.; Kwong, J.C.; Forchuk, C.; Dosani, N.; Booth, R. COVID-19 vaccine coverage and factors associated with vaccine uptake among 23 247 adults with a recent history of homelessness in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e366–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Romero, R.; Guha, P.; Sixx, G.; Rosen, A.D.; Frederes, A.; Beltran, J.; Alvarado, J.; Robie, B.; Richard, L.; et al. Community Health Worker Perspectives on Engaging Unhoused Peer Ambassadors for COVID-19 Vaccine Outreach in Homeless Encampments and Shelters. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 2026–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, J.S.; D’Amico, E.J.; Pedersen, E.R.; Garvey, R.; Rodriguez, A.; Klein, D.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Rates and Attitudes Among Young Adults With Recent Experiences of Homelessness. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 70, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, L.; Filter, M.; McFarland, M. Increasing influenza vaccination acceptance in the homeless: A quality improvement project. Nurse Pr. 2019, 44, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechler, C.R.; Ukani, A.; Elsharawi, R.; Gable, J.; Petersen, A.; Franklin, M.; Chung, R.; Bell, J.; Manly, A.; Hefzi, N.; et al. Barriers, beliefs, and practices regarding hygiene and vaccination among the homeless during a hepatitis A outbreak in Detroit, MI. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, K.L.; Chu, S.; Giles, M. Factors influencing the uptake of influenza vaccine vary among different groups in the hard-to-reach population. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker, J. More Than 95% of Active Duty Have Received COVID-19 Vaccine. Military Health System. 15 October 2021. Available online: https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2021/10/15/More-Than-95-Percent-of-Active-Duty-Have-Received-COVID-19-Vaccine?type=Photos (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Stewart, P.; Ali, I. As Delta Surges, U.S. Military Braces for Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccines. Reuters. 3 August 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/delta-surges-us-military-braces-mandatory-covid-19-vaccines-2021-08-03/ (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Liebermann, O.; Kaufman, E. US Military Says a Third of Troops Opt Out of Being Vaccinated, But the Numbers Suggest It’s More. CNN. 19 March 2021. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/19/politics/us-military-vaccinations (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Gin, J.L.; Balut, M.D.; Dobalian, A. Vaccines, Military Culture, and Cynicism: Exploring COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes among Veterans in Homeless Transitional Housing. Mil. Behav. Health 2022, 10, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanshani, S.; Wittenberg, S.; Bryce, R. Attitudes and Barriers toward COVID-19 Vaccination among People Experiencing Homelessness in Detroit, MI; Medical Student Research Symposium; Wayne State University: Detroit, MI, USA, 2022; Available online: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/som_srs/176 (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Gin, J.; Kranke, D.; Weiss, E.; Dobalian, A. Military Culture and Cultural Competence in Public Health: U.S. Veterans and SARS CoV-2 Vaccine Uptake. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2022; forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, L. Veterans and Homelessness. Congressional Research Service. 6 November 2015. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL34024.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Tsai, J.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Szymkowiak, D. The Problem of Veteran Homelessness: An Update for the New Decade. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, J.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Kasprow, W.J. Patient and Program Predictors of 12-Month Outcomes for Homeless Veterans Following Discharge from Time-Limited Residential Treatment. Adm. Ment. Health 2010, 38, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.; Kasprow, W.J.; Rosenheck, R.A. Latent homeless risk profiles of a national sample of homeless veterans and their relation to program referral and admission patterns. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, S239–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Grant and Per Diem Program-Homeless Veterans. 19 July 2018. Available online: www.va.gov/homeless/gpd.asp (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Balut, M.D.; Gin, J.L.; Alenkin, N.R.; Dobalian, A. Vaccinating Veterans Experiencing Homelessness for COVID-19: Healthcare and Housing Service Providers’ Perspectives. J. Community Health 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gin, J.L.; Balut, M.D.; Alenkin, N.R.; Dobalian, A. Responding to COVID-19 While Serving Veterans Experiencing Homelessness: The Pandemic Experiences of Healthcare and Housing Providers. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Schulz, W.S.; Chaudhuri, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dubé, E.; Schuster, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Wilson, R.; The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, R.; Wu, J.; Erhardt, T. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Henshall, C.; Kenyon, S.; Litchfield, I.; Greenfield, S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded Theory Research—Procedures, Canons and Evaluative Criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel, P.; Ward, J.K.; Schulz, W.S.; Verger, P.; Larson, H.J. Vaccine Hesitancy: Clarifying a Theoretical Framework for an Ambiguous Notion. PLoS Curr. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, S.; Jamison, A.; Musa, D.; Hilyard, K.; Freimuth, V. Exploring the Continuum of Vaccine Hesitancy between African American and White Adults: Results of a Qualitative Study. PLoS Curr. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chor, J.S.; Pada, S.K.; Stephenson, I.; Goggins, W.B.; Tambyah, P.A.; Clarke, T.W.; Medina, M.; Lee, N.; Leung, T.F.; Ngai, K.L.; et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination predicts pandemic H1N1 vaccination uptake among healthcare workers in three countries. Vaccine 2011, 29, 7364–7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frew, P.M.; Painter, J.E.; Hixson, B.; Kulb, C.; Moore, K.; del Rio, C.; Esteves-Jaramillo, A.; Omer, S.B. Factors mediating seasonal and influenza A (H1N1) vaccine acceptance among ethnically diverse populations in the urban south. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4200–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCosker, L.K.; El-Heneidy, A.; Seale, H.; Ware, R.S.; Downes, M.J. Strategies to improve vaccination rates in people who are homeless: A systematic review. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3109–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwy, A.R.; Clayman, M.L.; LoBrutto, L.; Miano, D.; Petrakis, B.A.; Javier, S.; Erhardt, T.; Midboe, A.M.; Carbonaro, R.; Jasuja, G.K.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy as an opportunity for engagement: A rapid qualitative study of patients and employees in the U.S. Veterans Affairs healthcare system. Vaccine X 2021, 9, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, V.; Racine, M.; Hwang, S.W. COVID-19 vaccination amongst persons experiencing homelessness: Practices and learnings from UK, Canada and the US. Public Health 2021, 199, e2–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, A.; Holder, J. They Haven’t Gotten a Covid Vaccine Yet. But They Aren’t ‘Hesitant’ Either. The New York Times. 12 May 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/12/us/covid-vaccines-vulnerable.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Kuhn, R.; Henwood, B.; Lawton, A.; Kleva, M.; Murali, K.; King, C.; Gelberg, L. COVID-19 vaccine access and attitudes among people experiencing homelessness from pilot mobile phone survey in Los Angeles, CA. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.-T.; Petering, R.; Onasch-Vera, L. Implications of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among young adults experiencing homelessness: A brief report. J. Soc. Distress Homelessness 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasuja, G.K.; Meterko, M.; Bradshaw, L.D.; Carbonaro, R.; Clayman, M.L.; LoBrutto, L.; Miano, D.; Maguire, E.M.; Midboe, A.M.; Asch, S.M.; et al. Attitudes and Intentions of US Veterans Regarding COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2132548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.; Zerger, S.; Wolfe, P.B. Health Care for the Homeless: What We Have Learned in the Past 30 Years and What’s Next. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, S199–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settembrino, M.R. ‘Sometimes You Can’t Even Sleep at Night’: Social Vulnerability to Disasters among Men Experiencing Homelessness in Central Florida. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 2017, 35, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Edgington, S. Disaster Planning for People Experiencing Homelessness; National Health Care for the Homeless Council: Nashville, TN, USA, 2009; pp. 1–51. Available online: https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Disaster-Planning-for-People-Experiencing-Homelessness.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Care for Homeless People. Homelessness, Health, and Human Needs; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1988. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218235/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Oreskes, B. Vaccinating the Homeless Population for COVID Adds a Whole New Layer of Difficulty. Los Angeles Times. 15 February 2021. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2021-02-15/la-homeless-covid-vaccine-distribution-extra-difficult?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Albrecht, D. Vaccination, politics and COVID-19 impacts. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Grant and Per Diem: COVID-19 FAQs; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Homeless Programs Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Garg, S.; Kim, L.; Whitaker, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Cummings, C.; Holstein, R.; Prill, M.; Chai, S.J.; Kirley, P.D.; Alden, N.B.; et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, 1–30 March 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentsch, C.T.; Kidwai-Khan, F.; Tate, J.P.; Park, L.S.; King, J.T., Jr.; Skanderson, M.; Hauser, R.G.; Schultze, A.; Jarvis, C.I.; Holodniy, M.; et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gin, J.L.; Balut, M.D.; Dobalian, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among U.S. Veterans Experiencing Homelessness in Transitional Housing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315863

Gin JL, Balut MD, Dobalian A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among U.S. Veterans Experiencing Homelessness in Transitional Housing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315863

Chicago/Turabian StyleGin, June L., Michelle D. Balut, and Aram Dobalian. 2022. "COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among U.S. Veterans Experiencing Homelessness in Transitional Housing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315863

APA StyleGin, J. L., Balut, M. D., & Dobalian, A. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among U.S. Veterans Experiencing Homelessness in Transitional Housing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315863