Digital Forms of Commensality in the 21st Century: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Scoping Review Approach

2.2. Study Identification and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

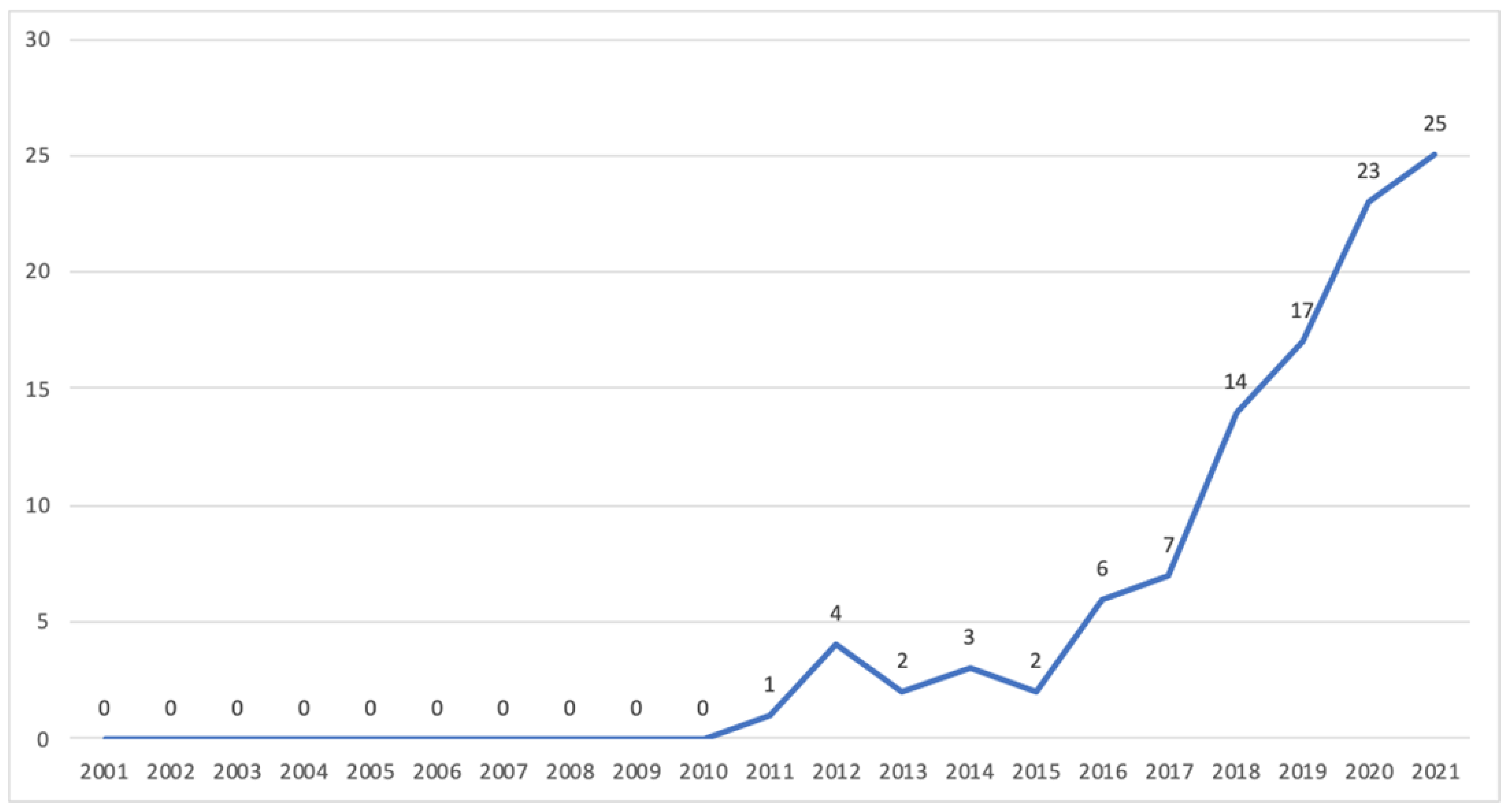

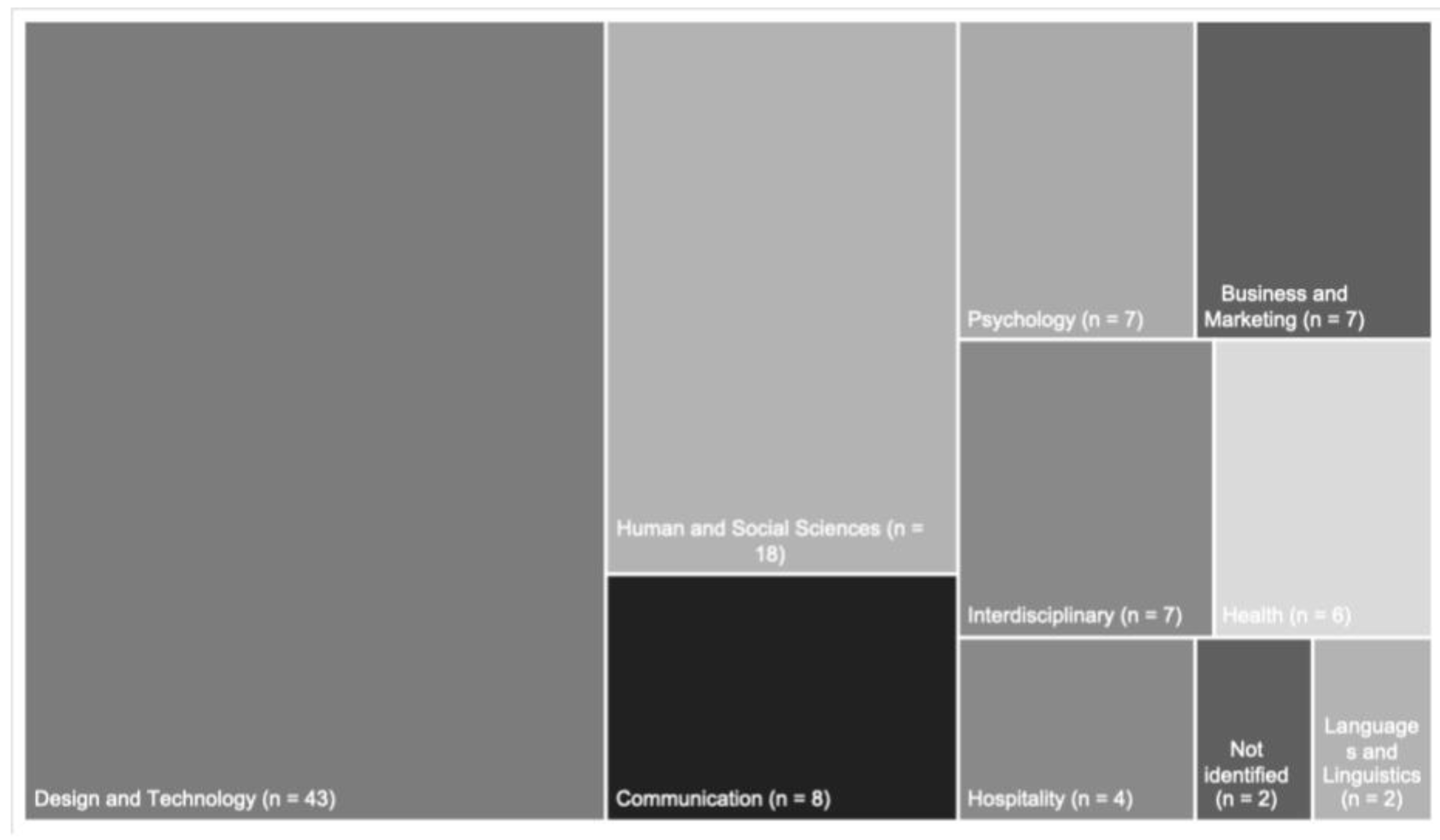

3.1. Search Results and Study Characteristics

3.2. Understanding Commensality

3.3. The Technological Landscape of Commensality

3.4. Commensality and Health

3.5. Representations of Eating Together

3.5.1. Eating Together Remotely and Solo-Eating with Technology

3.5.2. Family Meals with Children Using an Electronic Device at the Table

3.5.3. Virtual Communities about Food

3.5.4. Sharing and Gaming

3.5.5. Commercial Relationships in Digital Forms of Commensality

3.5.6. Eating Together in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Discussion

4.1. About the Main Study Characteristics

4.2. Technology as Emerging Scholar Field for Contemporary Commensalities Studies

4.3. A Social Phenomenon with a Conceptual and Symbolic Heterogeneity

4.4. About Health Topics Identified

4.5. Eating Together in a Digital World

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreira, S.A. Alimentação e comensalidade: Aspectos históricos e antropológicos [Food and Commensality: Historical and Anthropological Aspects]. Cienc. Cult. 2010, 62, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. Simmel on Culture: Selected Writings; Part III; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1997; pp. 130–136. ISBN 0803986521. [Google Scholar]

- Zuin, P.; Zuin, L. Tradição e Alimentação [Tradition and Food]; Ideias e Letras: Aparecida, SP, Brazil, 2009; ISBN 978-8576980384. [Google Scholar]

- Flandrin, J.L.; Montanari, M. História da Alimentação [History of Diet]; Estação Liberdade: São Paulo, Brazil, 1998; pp. 667–688. ISBN1 8574480029. ISBN2 9788574480022. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, J. Sociologias da Alimentação [Sociologies of Food]; UFSC: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2004; ISBN 978-85-328-0654-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, C. Commensality, society and culture. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2011, 50, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Neto, J.; Farias, R. Alimentação, comida e cultura: O exercício da comensalidade [Diet, food and culture: The commensality excersice]. DEMETRA Aliment. Nutr. Saúde 2015, 10, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scagliusi, F.; Pereira, P.R.; Unsain, R.; Sato, P.M. Eating at the table, on the couch and in bed: An exploration of different locus of commensality in the discourses of Brazilian working mothers. Appetite 2016, 103, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy, P. O Que é o Virtual? [What is the Virtual], 2nd ed.; Editora 34: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011; ISBN 978-8573260366. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenes-Minasse, M.H.; Drudi, P.H.; Faltin, A.O.; Lopes, M.S. Comensalidade.com—Uma reflexão introdutória sobre as novas tecnologias e as práticas do comer junto [Commensality.com—An introductory reflection on new technologies and practices of eating together]. Rev. Hosp. 2018, 15, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Juárez, L.M.; Medina, X. Comida y Mundo Virtual [Food and Virtual World]; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-8491167259. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C.; Mancini, M.; Huisman, G. Digital Commensality: Eating and Drinking in the Company of Technology. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tooming, U. Aesthetics of food porn. Crit. Rev. Hispanoam. De Filos. 2021, 53, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Welcome to Cyberia: Notes on the Anthropology of Cyberculture [and Comments and Reply]. Curr. Anthropol. 1994, 35, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, S. Cook it, eat it, Skype it: Mobile media use in re-staging intimate culinary practices among transnational families. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2019, 22, 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevet, C.; Tang, A.; Mynatt, E. Eating Alone, Together: New Forms of Commensality. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, 27–31 October 2012; pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koponen, S.; Mustonen, P. Eating alone, or commensality redefined? Solo dining and the aestheticization of eating (out). J. Consum. Cult. 2020, 22, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G. Eating (alone) with Facebook: Digital natives’ transition to college. First Monday Peer-Rev. J. Internet 2018, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. The use of ICT devices as part of the solo eating experience. Appetite 2021, 165, 1–905297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircaburun, K.; Harris, A.; Calado, F.; Griffiths, M.D. The Psychology of Mukbang Watching: A Scoping Review of the Academic and Non-academic Literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 19, 1190–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jönsson, H.; Michaud, M.; Neuman, N. What is commensality? A critical discussion of an expanding research field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015 Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medina, J.A.V.; Bayre, F. Comida y Mundo Virtual: Internet, Redes Sociales y Representaciones Visuales; Editorial UOC: Catalunya, Spain, 2018; Chapter IV; pp. 87–103. ISBN 978-8491167259. [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomski, R.; Ceccaldi, E.; Huisman, G.; Volpe, G.; Mancini, M. Computational Commensality: From Theories to Computational Models for Social Food Preparation and Consumption in HCI. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, D.; Bjøner, T.; Bruun-Pedersen, J.R.; Sørensen, P.K. Older adults eating together in a virtual living room: Opportunities and limitations of eating in augmented virtuality. In Proceedings of the 31st European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics, Belfast, UK, 10–13 September 2019; pp. 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W. Food media: Food and technology as a medium for social communication. Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Panicker, A.; Basu, K.; Chung, C.F. Changing Roles and Contexts: Symbolic Interactionism in the Sharing of Food and Eating Practices between Remote, Intergenerational Family Members. Proc. ACM Hum. -Comput. Interact. 2020, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.J. Pass the iPad: Assessing the Relationship between Tech Use during Family Meals and Parental Reports of Closeness to Their Children. Sociol. Q. 2019, 60, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Ferdous, H.S. Vetere, F “Table manners”: Children’s use of mobile technologies in family-friendly restaurants. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertran, F.; Pometko, A.; Gupta, M.; Wilcox, L.; Banerjee, R.; Isbister, K. The Playful Potential of Shared Mealtime: A Speculative Catalog of Playful Technologies for Day-to-day Social Eating Experiences. Proc. ACM Hum. -Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y. Designing Playful Technology for Young Children’s Mealtime. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, H.; Ploderer, B.; Davis, H.; Vetere, F.; Farr-Wharton, G.; Comber, R. TableTalk: Integrating Personal Devices and Content for Commensal Experiences at the Family Dinner Table. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Heidelberg, Germany, 12–16 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, H.S.; Ploderer, B.; Davis, H.; Vetere, F.; O’Hara, K. Commensality and the social use of technology during family mealtime. ACM Trans. Comput. -Hum. Interact. 2016, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferdous, H.S.; Vetere, F.; Davis, H.; Ploderer, B.; O’Hara, K.; Comber, R.; Farr-Wharton, G. Celebratory technology to orchestrate the sharing of devices and stories during family mealtimes. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 6960–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lavis, A. Food porn, pro-anorexia and the viscerality of virtual affect: Exploring eating in cyberspace. Geoforum 2017, 84, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendini, M.; Pizzetti, M.; Peter, P.C. Social food pleasure: When sharing offline, online and for society promotes pleasurable and healthy food experiences and well-being. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2019, 22, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.; Engelbutzeder, P.; Ludwig, T. “Always on the Table”: Revealing Smartphone Usages in everyday Eating Out Situations. In Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, Tallinn, Estonia, 25–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.M.; McCarthy, M.B. Fast food and fast games: An ethnographic exploration of food consumption complexity among the videogames subculture. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 720–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P.; Khot, R.A.; Mueller, F. “You better eat to survive”: Exploring cooperative eating in virtual reality games. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Stockholm, Sweden, 28–21 March 2018; pp. 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashihara, A.; Yamaguchi, T. A development of color lighting device to indicate subjective palatability. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–15 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavioli, M.; Bastos, S. La hospitalidad en la escena gastronómica: Sitios de internet de comida compartida [Hospitality in the gastronomic scene: Shared Food Websites]. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2020, 29, 958–974. [Google Scholar]

- Paay, J.; Kjeldskov, J.; Skov, M.B.; O’Hara, K. Cooking together. In Proceedings of the CHI ‘12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, Texas, USA, 5–10 May 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paay, J.; Kjeldskov, J.; Skov, M.; O’hara, K. F-Formations in Cooking Together: A Digital Ethnography Using YouTube. In Proceedings of the 14th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 2–6 September 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemsi-Paillissé, A.; Acosta Meneses, Y.; Martinez, M.; Calvo Gutiérrez, E. Application of the critique of dispositives to the performative dinner “El Somni” by El Celler de Can Roca and Fran Aleu. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1267–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, N.; Hakaraia, D. The use of Maori and Pasifika knowledge within the everyday practice of commensality to enrich the learning experience. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. South 2018, 2, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Li, Z.; Rosner, D.; Hiniker, A. Understanding Parents’ Perspectives on Mealtime Technology. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2019, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M. Cοntributiοns des Médias Sοciaux aux Représentatiοns et aux Pratiques d’une Alimentatiοn Saine chez les Jeunes [Social Media Contributiοns to Representatiοns and Healthy Eating Practices in Young People]. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Le Havre Normandie, La Havre, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Donnar, G. ‘Food porn’ or intimate sociality: Committed celebrity and cultural performances of overeating in meokbang. Celebr. Stud. 2017, 8, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Z.; Goodman, M. Digital food culture, power and everyday life. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2021, 24, 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, H.S. Technology at mealtime: Beyond the “ordinary”. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, H.S.; Ploderer, B.; Davis, H.; Vetere, F.; O’Hara, K. Pairing technology and meals: A contextual enquiry in the family household. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest Group for Computer Human Interaction, Parkville, VIC, Australia, 7–10 December 2015; pp. 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, H. Technology at Family Mealtimes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khot, R.A.; Kurra, H.; Arza, E.S.; Wang, Y. FObo: Towards designing a robotic companion for solo dining. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, H.; Şimşek Kandemir, A.; Uçkun, S.; Karaman, E.; Yüksel, A.; Onay, Ö.A. The Presence of Smartphones at Dinnertime: A Parental Perspective. Fam. J. 2020, 28, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Y.D.; Khot, R.A.; Patibanda, R.; Mueller, F.F. “Arm-a-dine”: Towards understanding the design of playful embodied eating experiences. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K.; Helmes, J.; Sellen, A.; Harper, R. Food for talk: Phototalk in the context of sharing a meal. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2012, 27, 124–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, M.; Castro, L.; Favela, J. Understanding changes in behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: Opportunities to design around new eating experiences. Av. Interacción Hum. Comput. 2021, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, A. Technologies are Coming over for Dinner: Do Ritual Participation and Meaning Mediate Effects on Family Life? Master’ Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugual, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rimoldi, L. Eating Online Discourses: Rhetorics on Food Consumption in Contemporary Bicocca (Milan, Italy). J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2014, 4, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haque, J.K. Synchronized Dining Tangible Mediated Communication for Remote Commensality. Master’s Thesis, Malmo University, Malmo, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, G. Exploring Possibilities to Improve Distant Dining Experience for Young Expats with their Loved Ones over Time and Space Gap Issues. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Peng, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wan, X. Cloud-Based Commensality: Enjoy the Company of Co-diners without Social Facilitation of Eating. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, S. Digital food and foodways: How online food practices and narratives shape the Italian diaspora in London. J. Mater. Cult. 2017, 23, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, S.; Wittkop, T. Virtual wine tastings—How to ‘zoom up’ the stage of communal experience. J. Wine Res. 2021, 32, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourat, E.; Fournier, T.; Lepiller, O. Reflection: Snatched Commensality: To eat or not to eat together in times of COVID-19 in France. Food Foodways 2021, 29, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaldi, E.; Huisman, G.; Volpe, G.; Mancini, M. Guess who’s coming to dinner? Surveying digital commensality during COVID-19 outbreak. In Proceedings of the ICMI ‘20 Companion: Companion Publication of the 2020 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Virtual Event, Netherlands, 25–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra, G.A. Quarantined sobremesa. Creat. Food Cycles 2020, 1, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Kubota, S.; Zhanghe, J.; Inoue, T. Effects of Dietary Similarity on Conversational and Eating Behaviors in Online Commensality. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference, CollabTech 2021, Virtual Event, 31 August–3 September 2021; pp. 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barden, P.; Comber, R.; Green, D.; Jackson, D.; Ladha, C.; Bartindale, T.; Bryan-Kinns, N.; Stockman, T.; Olivier, P. Telematic dinner party: Designing for togetherness through play and performance. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, DIS’12, Newcastle, UK, 11–15 June 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenni, I.; Vásquez, C. Reflection: Airbnb’s food-related “online experiences”: A recipe for connection and escape. Food Foodways 2020, 29, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisker, L. Eating and togetherness in “long-distance families” Eating Means We Love You. Master’s Thesis, Malmo University, Malmo, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, C.P.; Niewiadomski, R.; Bruijnes, M.; Huisman, G.; Mancini, M. Eating with an artificial commensal companion. In Proceedings of the ICMI 2020 Companion-Companion Publication of the 2020 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Virtual Event Netherlands, 25–29 October 2020; pp. 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, R.A.; Aggarwal, D. Guardian of the Snacks: Toward designing a companion for mindful snacking. Multimodality Soc. 2021, 1, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitakunye, P.; Takhar, A. Consuming family quality time: The role of technological devices at mealtimes. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1162–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.; Krings, K.; Nießner, J.; Brodesser, S.; Ludwig, T. FoodChattAR: Exploring the Design Space of Edible Virtual Agents for Human-Food Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference: Nowhere and Everywhere, Virtual, USA, 28 June 2021–2 July 2021; pp. 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barre, L.K.; Coupal, S.; Young, T. Videodining in older adults aging in place: A feasibility and acceptability study. Innov. Aging 2020, 3, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, N.; Guo, Z.; Nakata, R. Watching a remote-video confederate eating facilitates perceived taste and consumption of food. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 238, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Niewiadomski, R.; Huisman, G.; Bruijnes, M.; Gallagher, C.P. Room for one more? Introducing artificial commensal companions. In Proceedings of the CHI EA ‘20: Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, E.; Bubendorff, S.; Fraïssé, C. Toward new forms of meal sharing? Collective habits and personal diets. Appetite 2018, 123, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kera, D.; Sulaiman, N.L. FridgeMatch: Design probe into the future of urban food commensality. Futures 2014, 62, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urie, G.J. Pop-ups, Meetups and Supper Clubs: An exploration into Online Mediated Commensality and its role and significance within contemporary hospitality provision. Ph.D. Thesis, Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, Scotland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, R.; Haapio-Kirk, L.; Kimura, Y. Sharing Virtual Meals Among the Elderly: An ethnographic and quantitative study of the role of smartphones in distanced social eating in rural Japan. Jpn. Rev. Cult. Anthropol. 2020, 21, 7–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, N.; Guo, Z.; Nakata, R. A human voice, but not human visual image makes people perceive food to taste better and to eat more: “Social” facilitation of eating in a digital media. Appetite 2021, 167, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenes-Minasse, M.H. Novas configurações do comer junto—Reflexões sobre a comensalidade contemporânea na cidade de São Paulo (Brasil) [New configurations of eating together—Reflections on contemporary commensality in the city of São Paulo (Brazil)]. Rev. Hosp. 2017, 25, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pennell, M. (Dis)comfort food—Connecting food, social media, and first-year college undergraduates. Food Cult. Soc. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2018, 21, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varella, H.; Machado, M. Digital Ethnography of Living Food: A Methodological Approach to Online and Offline Fieldwork. Athenea Digit. 2021, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Guo, Z.; Liang, R.-H. Asynchronous Co-Dining: Enhancing the Intimacy in Remote Co-Dining Experience Through Audio Recordings. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Salzburg, Austria, 14–17 February 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjani, L.; Mok, T.; Tang, A.; Oehlberg, L.; Goh, W.B. Why do people watch others eat food? An Empirical Study on the Motivations and Practices of Mukbang Viewers. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, J. Virtual Commensality—Mukbang and Food Television. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canadá, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, H. Eating together multimodally: Collaborative eating in mukbang, a Korean livestream of eating. Lang. Soc. 2019, 48, 171–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strand, M.; Gustafsson, S.A. Mukbang and Disordered Eating: A Netnographic Analysis of Online Eating Broadcasts. Cult. Med. Psychiatrym 2020, 44, 586–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, M.; Babenkaite, G. Mukbang Influencers—Online eating becomes a new marketing strategy. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, L. “The Toad Wants to Eat the Swan?” A Study of Rural Female Chibo through Short Video Format on E-commerce Platforms in China. Media J. 2020, 18, 1–6. Available online: https://www.globalmediajournal.com/open-access/the-toad-wants-to-eat-the-swan-a-study-of-rural-female-chibo-through-short-video-format-on-ecommerce-platforms-in-china.php?aid=88327 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Gillespie, S.; Hanchey, J.N.; Advisor, T. Watching Women Eat: A Critique of Magical Eating and Mukbang Videos. Mater’s Thesis, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, E.K.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.H.; Yun, Y.H. The popularity of eating broadcast: Content analysis of “mukbang” YouTube videos, media coverage, and the health impact of “mukbang” on public. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Yun, S.; Lee, H. Dietary life and mukbang- and cookbang-watching status of university students majoring in food and nutrition before and after COVID-19 outbreak. J. Nutr. Health 2021, 54, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; An, S. Binge drinking and obesity-related eating: The moderating roles of the eating broadcast viewing experience among Korean adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Eating as a transgression: Multisensorial performativity in the carnal videos of mukbang (eating shows). International J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 24, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Stavropoulos, V.; Harris, A.; Calado, F.; Emirtekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Development and Validation of the Mukbang Addiction Scale. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 19, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kircaburun, K.; Yurdagül, C.; Kuss, D.; Emirtekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Problematic Mukbang Watching and Its Relationship to Disordered Eating and Internet Addiction: A Pilot Study Among Emerging Adult Mukbang Watchers. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 19, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Balta, S.; Emirtekin, E.; Tosuntas, S.B.; Demetrovics, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. Compensatory Usage of the Internet—The Case of Mukbang Watching on YouTube. Korean Neuropsychiatric Association. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Sung, B.; Lee, S. I like watching other people eat: A cross-cultural analysis of the antecedents of attitudes towards Mukbang. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L. Waste on the Tip of the Tongue: Social Eating Livestreams (Chibo) in the Age of Chinese Affluence. Asiascape Digit. Asia 2021, 8, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwegler-Castañer, A. At the intersection of thinness and overconsumption: The ambivalence of munching, crunching, and slurping on camera. Fem. Media Stud. 2018, 18, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. A study on potential health issues behind the popularity of “mukbang” in China. Master’s Thesis, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J.; Yeo, J. Investigating meal-concurrent media use: Social and dispositional predictors, intercultural differences, and the novel media phenomenon of “mukbang” eating broadcasts. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Does watching mukbangs help you diet? The effect of the mukbang on the desire to eat. Master’s Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.; Kang, H.; Lee, H. Mukbang-and cookbang-watching status and dietary life of university students who are not food and nutrition majors. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2020, 14, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastasin, G. Social Eating: Una Ricerca Qualitativa su Motivazioni, Esperienze e Valutazioni Degli Utenti della Piattaforma VizEat.com [Social Eating: A Qualitative Research on the Motivations, Experiences and Ratings of Users of the VizEat.com platform]. Master’s Thesis, Universitá di Pisa, Pisa, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Macia, C.F.; Mairano, M.V. El comer en el siglo XXI: Una aproximación a las sensibilidades en torno a la comida en Instagram [Eating in the 21st century: An approach to the sensitivities around food on Instagram]. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 90, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pimiento, O. Peligro en el plato: Rumores y leyendas urbanas del tema alimentario en internet [Danger on the plate: Rumors and urban legends of food on the internet]. Rev. Colomb. De Sociol. 2018, 41, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stano, S. Mauvais à regarder, bon à penser: Il food porn tra gusti e disgusti [Bad to look at, good to think about: Il food porn tra gusti e disgusti]. E|C Online 2018, 23, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar, B. Share my meal: A Social Catalyst for Interactions Around Food. Master’s Thesis, School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, F.F.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Kari, T.; Arnold, P.; Mehta, Y.D.; Marquez, J.; Khot, R.A. Towards experiencing eating as play. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–12 February 2020; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moser, C.; Schoenebeck, S.Y.; Reinecke, K. Technology at the table: Attitudes about mobile phone use at mealtimes. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, A.C.A.G. TableTalk: Staging Intimacy Across Distance Through Shared Meals. J. Theatre Perform. Arts 2018, 12, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Giard, A. Comer com um robô para recuperar a confiança. Refeições, role-playing e comunicação no Japão [Eating with a robot to regain confidence. Dining, role-playing and communication in Japan]. Hermès La Rev. 2021, 88, 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko, L.; Meshcheryakova, N.; Zotov, V. Digitalization of Global Society: From the Emerging Social Reality to its Sociological Conceptualisation. Wisdom 2022, 21, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, M. Understanding Media; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0262631594. [Google Scholar]

- Scander, H.; Yngve, A.; Wiklund, M.L. Assessing commensality in research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K. Diet and Health Benefits Associated with In-Home Eating and Sharing Meals at Home: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusienė, R. Screen Use During Meals Among Young Children: Exploration of Associated Variables. Medicina 2019, 55, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira [Food Guide for the Brazilian Population]; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014.

- Government of Canada. Canada’s Food Guide; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020.

- Granheim, S.I. The digital food environment. UNSCN Nutr. 2019, 44, 115–121. Available online: https://www.unscn.org/uploads/web/news/UNSCN-Nutrition44-WEB-21aug.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Debord, G. Society of the Spectacle; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0942299809. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, J. 24/7 Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep; Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1781683101. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. No Enxame: Perspectivas do Digital [In the Swarm: Perspectives of the Digital]; Editora Vozes Limitada: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2018; ISBN 978-8532658517. [Google Scholar]

| Concepts | Description | Terms Used In The Sample Publications | Corresponding References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commensality | In this case, the commensality addressed in the selected studies, despite being mediated by technology, is not used with a specific term that differentiates it from traditional commensality. | Commensality Cooperative eating Dinnertime ritual Eating experience Eating together Family mealtimes Food sharing Shared meals Sharing food experience Social eating Social eating experience | [10,17,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] |

| Remote Commensality | The practice of eating together is remote, that is, each diner is located in a different physical environment and, therefore, they meet virtually to share a meal through videoconferencing. | Cloud-based commensality Digital commensality Distant Dining Food rituals in the new media space Online Commensality/Remote co-eating Remote commensality Remote dinner or commensality across distance or long-distance commensality Virtual commensality | [49,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75] |

| Computational Commensality | Commensality is achieved through technological artifacts used by diners or even through interaction with interactive robots. | Artificial commensality Computational commensality Digital and computational forms of commensality Digital commensality Eating together multimodally Long distance commensality Multitasking at mealtime Remote commensality | [18,29,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] |

| Digital commensality | Commensality occurs asynchronously, mediated by text, image, or video posts and instant messages | Commensality through smartphones Contemporary commensality Digital commensality (also food porn) Computational commensality Digital food sharing Mediated commensality and online mealtime socialization New forms of commensality Online mediated commensality Remote co-dining experience Virtual commensality | [16,19,28,68,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

| Commensality mediated by live broadcasts | Commensality occurs through a person having a meal (or cooking) alone and broadcasting that act to others through video platforms | Cookbang and mukbang Digital commensality Eating broadcast viewing experience Eating together multimodally Mukbang and Chibo (online meal broadcasts) Online eating Virtual commensality | [12,20,54,67,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113] |

| Type of Technology Cited in the Publication (n) | Corresponding References |

|---|---|

| Social networks, applications, blogs, and websites (n = 32) | [10,13,17,20,32,28,36,39,40,41,46,52,54,58,62,70,84,86,87,89,90,91,92,103,104,108,114,115,116,117,118] |

| Video and live streaming platforms (n = 23) | [12,47,48,53,54,55,56,82,93,94,95,96,97,100,102,105,106,107,109,110,111,112,113] |

| Tabletop use prototypes (Ex: Augmented Reality) (n = 19) | [12,16,29,30,31,35,36,43,44,45,49,51,52,61,65,77,80,88,119] |

| Mobile devices (n = 17) | [33,34,35,38,42,56,57,59,63,73,76,73,76,79,81,99,120] |

| Videoconferencing tools (n = 14) | [15,18,24,27,50,62,65,67,68,69,81,89,101,121] |

| Television sets (n = 6) | [19,33,38,79,102,108] |

| Robots (n = 6) | [58,60,77,78,83,122] |

| Commercial platforms (n = 5) | [64,75,85,89,98] |

| Computers (n = 3) | [19,38,99] |

| Categories (n) | Corresponding References |

|---|---|

| Impact on eating habits (n = 20) | [12,19,36,41,42,44,51,66,73,74,78,80,82,87,101,102,104,110,112,113] |

| Impact on mental health (n = 6) | [41,77,82,88,106,122] |

| Family and community engagement (n = 5) | [15,19,32,89,91] |

| Appreciation of local food culture (n = 3) | [64,68,116] |

| Formulation of public health policies (n = 2) | [72,115] |

| Culinary skill development (n = 1) | [48] |

| (Un)sustainability practices (n = 1) | [108] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira-Castro, M.R.; Pinto, A.G.; Caixeta, T.R.; Monteiro, R.A.; Bermúdez, X.P.D.; Mendonça, A.V.M. Digital Forms of Commensality in the 21st Century: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416734

Pereira-Castro MR, Pinto AG, Caixeta TR, Monteiro RA, Bermúdez XPD, Mendonça AVM. Digital Forms of Commensality in the 21st Century: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416734

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira-Castro, Maína Ribeiro, Adriano Gomes Pinto, Tamila Raposo Caixeta, Renata Alves Monteiro, Ximena Pamela Díaz Bermúdez, and Ana Valéria Machado Mendonça. 2022. "Digital Forms of Commensality in the 21st Century: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416734