Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nurses Working in Long-Term Care Facilities

Abstract

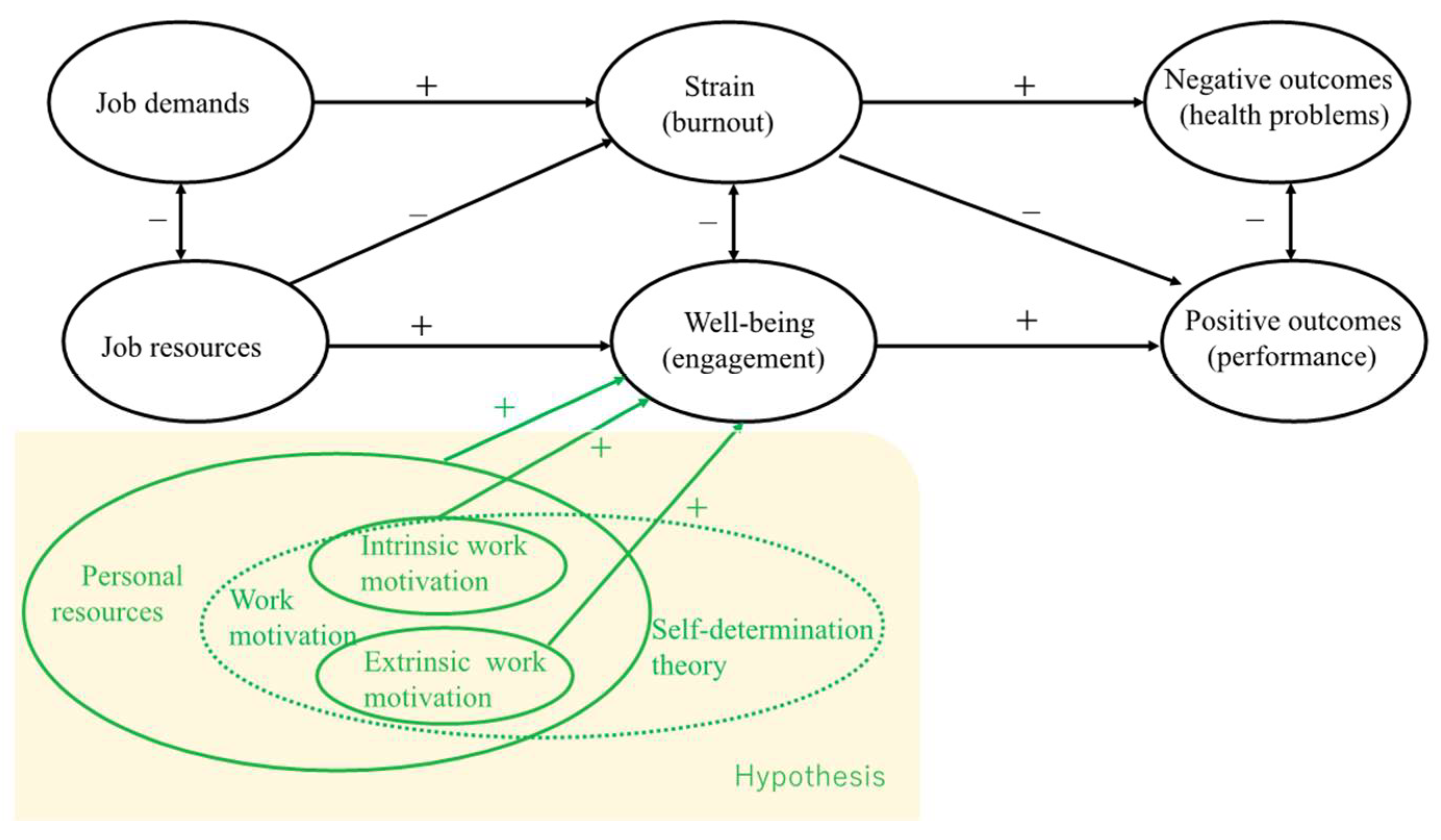

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Variables

2.2.2. Work Engagement

2.2.3. Job Satisfaction

2.2.4. Work Motivation for Employment in LTC Facilities

2.3. Data Analyses

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Work Motivation

3.2. Reliability

3.3. Work Engagement

3.4. Impact of Work Motivation on Work Engagement

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Work Motivation on Work Engagement

4.2. Contributions to Nursing Practice and the JD–R Model Theory

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living Arrangements of Older Persons (ST/ESA/SER.A/451). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd-2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- IAA News Release: IAA Releases Paper on Long Term Care-An Actuarial Perspective on Societal and Personal Challenges. Available online: https://www.actuaries.org/LIBRARY/News_Release/2017/NR_Apr10_EN.html (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Wilkinson, A.; Haroun, V.; Wong, T.; Cooper, N.; Chignell, M. Overall Quality Performance of Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario. Healthc. Q. 2019, 22, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White Paper on Ageing Society. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2021/zenbun/pdf/1s1s_01.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Long-Term Care Insurance Business Status Report Monthly Report. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/0103/tp0329-1.html (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese)

- Tsutsui, T. Implementation Process and Challenges for the Community-Based Integrated Care System in Japan. Int. J. Integr. Care 2014, 14, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arai, H.; Ouchi, Y.; Toba, K.; Endo, T.; Shimokado, K.; Tsubota, K.; Matsuo, S.; Mori, H.; Yumura, W.; Yokode, M.; et al. Japan as the Front-Runner of Super-Aged Societies: Perspectives from Medicine and Medical Care in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Community-Based Integrated Care System. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/kaigo_koureisha/chiiki-houkatsu/ (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Health Administration Report, 2018. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/eisei/18/dl/kekka1.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese)

- Japanese Nursing Association. Nursing Staff Fact-Finding Report at Long-Term Care Health Facilities and Long-Term Care Welfare Facilities: Turnover Rate for Nursing Staff and Care Staff. Available online: https://www.nurse.or.jp/home/publication/pdf/report/2016/kaigojittai.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Japanese Nursing Association. ‘Hospital Nursing Survey’ Results Report. Available online: https://www.nurse.or.jp/up_pdf/20180502103904_f.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Current Status of Securing Nursing Staff in Long-Term Care Facilities. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10801000/000483133.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese)

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement: An Emerging Concept in Occupational Health Psychology. BioSci. Trends 2008, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Arnold, B.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-Unit-Level Relationship Between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Bal, M.P. Weekly Work Engagement and Performance: A Study Among Starting Teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Wheeler, A.R. The Relative Roles of Engagement and Embeddedness in Predicting Job Performance and Intention to Leave. Work Stress. 2008, 22, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement and Financial Returns: A Diary Study on the Role of Job and Personal Resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, F.G., Hämming, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. An Evidence-Based Model of Work Engagement. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. A Cross-National Study of Work Engagement as a Mediator Between Job Resources and Proactive Behaviour. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vink, J.; Ouweneel, E.; Le Blanc, P. Psychologische Energiebronnen voor Bevlogen Werknemers: Psychologisch Kapitaal in Het Job Demands-Resources Model [Psychological resources for engaged employees: Psychological capital in the Job Demands-Resources Model]. Gedrag Organ. 2011, 24, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Smulders, P.; De Witte, H. Does an Intrinsic Work Value Orientation Strengthen the Impact of Job Resources? A Perspective from the Job Demands–Resources Model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simbula, S.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. A Three-Wave Study of Job Resources, Self-Efficacy, and Work Engagement Among Italian Schoolteachers. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Role of Personal Resources in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E.; Locke, E.A. Personality and Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Job Characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallonardo, L.M.; Wong, C.A.; Iwasiw, C.L. Authentic Leadership of Preceptors: Predictor of New Graduate Nurses’ Work Engagement and Job Satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatzky, J.A.; Enns, C.L. Exploring the Key Predictors of Retention in Emergency Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S. Job and Career Satisfaction and Turnover Intentions of Newly Graduated Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-L. Perceptions of Work Engagement of Nurses in Taiwan; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, C.M.; Roche, M.A.; Homer, C.; Buchan, J.; Dimitrelis, S. A Comparative Review of Nurse Turnover Rates and Costs Across Countries. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2703–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargagliotti, L.A. Work Engagement in Nursing: A Concept Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1414–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyko, K.; Cummings, G.G.; Yonge, O.; Wong, C.A. Work Engagement in Professional Nursing Practice: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 61, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources Model: A Three-Year Cross-Lagged Study of Burnout, Depression, Commitment, and Work Engagement. Work Stress. 2008, 22, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.R. Predictors of Work Engagement Among Medical-Surgical Registered Nurses. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 31, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. High-Performance Work Practices and Hotel Employee Performance: The Mediation of Work Engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.; Perryman, S.; Hayday, S. The Drivers of Employee Engagement Report 408; Institute for Employment Studies: Brighton, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, E.D.; Cho, S.; Liu, J. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement in the Hospitality Industry: Test of Motivation Crowding Theory. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.D.; Stimpfel, A.W. Nurse Reported Quality of Care: A Measure of Hospital Quality. Res. Nurs. Health 2012, 35, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Wouters, K.; Willems, R.; Mondelaers, M.; Clarke, S. Work Engagement Supports Nurse Workforce Stability and Quality of Care: Nursing Team-Level Analysis in Psychiatric Hospitals. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, Z.Y.; Rayton, B.A.; Rapti, A. Facets of Job Satisfaction and Work Engagement. Evid.-Based HRM 2017, 5, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, U.; Rajput, B. Work Engagement and Demographic Factors: A Study among University Teachers. J. Commer Acc. Res. 2021, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, S.; Roberts, R. Employee Age and The Impact on Work Engagement. Strat. HR Rev. 2020, 19, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Goel, A.; Sengupta, S. How Does Work Engagement Vary with Employee Demography?—Revelations from The Indian IT Industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 122, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Imai, H. Job Role Quality and Intention to Leave Current Facility and to Leave Profession of Direct Care Workers in Japanese Residential Facilities for Elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 54, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kosugi, S.; Suzuki, A.; Nashiwa, H.; Kato, A.; Sakamoto, M.; Irimajiri, H.; Amano, S.; Hirohata, K.; et al. Work Engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, A.A. Work Stress; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, K.; Maurits, E.E.M.; Francke, A.L. Attractiveness of Working in Home Care: An Online Focus Group Study Among Nurses. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2018, 26, e94–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C. On the Assessment of Situational Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion. Motiv. Emot. 2000, 24, 175–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurits, E.E.M.; de Veer, A.J.E.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Francke, A.L. Attractiveness of People-Centred and Integrated Dutch Home Care: A Nationwide Survey Among Nurses. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2018, 26, e523–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlson, E.; Rämgård, M.; Bolmsjö, I.; Bengtsson, M. Registered Nurses’ Perceptions of Their Professional Work in Nursing Homes and Home-Based Care: A Focus Group Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toode, K.; Routasalo, P.; Suominen, T. Work Motivation of Nurses: A Literature Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Watanabe, I.; Asakura, K. Occupational Commitment and Job Satisfaction Mediate Effort–Reward Imbalance and the Intention to Continue Nursing. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 14, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, K.; Kawakami, N.; Inoue, A.; Shimazu, A.; Tsutsumi, A.; Takahashi, M.; Totsuzaki, T. Work Engagement as a Predictor of Onset of Major Depressive Episode (MDE) Among Workers, Independent of Psychological Distress: A 3-Year Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.G.; Cabrera, E.M.S.; Gazetta, C.E.; Sodré, P.C.; Castro, J.R.; Cordioli Junior, J.R.; Cordioli, D.F.C.; Lourenção, L.G. Engagement in Primary Health Care Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Brazilian City. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Gancedo, J.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Rodríguez-Borrego, M.A. Relationships Among General Health, Job Satisfaction, Work Engagement and Job Features in Nurses Working in a Public Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.; Uwes, B.A. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale [Manual]. Preliminar (Versión 1.1). Utrecht University: Utrecht Países Bajos (2004). Available online: https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/Test%20Manuals/Test_manual_UWES_Espanol.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Navarro-Abal, Y. Relationship between Work Engagement, Psychosocial Risks, and Mental Health among Spanish Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 627472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wonder, A.C. Factors That Facilitate and Inhibit Engagement of Registered Nurses: An Analysis and Evaluation of Mag-Net Versus Non-Magnet Designated Hospitals. Ph.D. Thesis, The School of Nursing, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aboshaiqah, A.E.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Salem, O.A.; Zakari, N.M.A. The Work Engagement of Nurses in Multiple Hospital Sectors in Saudi Arabia: A Comparative Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, R.R.; Fitzpatrick, J.J.; Boyle, S.M. Closing the RN Engagement Gap: Which Drivers of Engagement Matter? J. Nurs. Admin. 2011, 41, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japanese Nursing Association. Survey Report on the Fact-Finding Survey of Nursing Workers Working in Elderly Care Facilities 2016. Measures to Strengthen Home-Visit Nursing to Support Long-Term Care Consumers [Online]. Available online: https://www.nurse.or.jp/home/publication/pdf/report/2016/kaigojittai.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022). (In Japanese).

- Bratt, C.; Gautun, H. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Nurses’ Wishes to Leave Nursing Homes and Home Nursing. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pélissier, C.; Charbotel, B.; Fassier, J.B.; Fort, E.; Fontana, L. Nurses’ Occupational and Medical Risks Factors of Leaving the Profession in Nursing Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hara, Y.; Asakura, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Takada, N.; Ito, Y.; Nihei, Y. Nurses Working in Nursing Homes: A Mediation Model for Work Engagement Based on Job Demands-Resources Theory. Healthcare 2021, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, E.; Wilson, T.D.; Brewer, M.B. Experimentation in Social Psychology. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 99–142. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common Method Variance in IS Research: A Comparison of Alternative Approaches and a Reanalysis of Past Research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 2, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variables | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD+) in years | 48.8 (±9.7) | |

| Mean years working at the current facility (SD+) in years | 7.7 (±6.3) | |

| Sex | Female | 516 (92) |

| Male | 45 (8) | |

| Marital status | Single | 100 (17.8) |

| Married | 422 (75.2) | |

| Divorced or widowed | 39 (7) | |

| Number of children | 0 | 108 (19.3) |

| 1+ | 453 (80.7) | |

| Types of long-term care facilities a | Long-term care welfare facilities | 252 (44.9) |

| Long-term care health facilities | 306 (54.5) | |

| Educational background a | Vocational school or junior college for registered nurses | 538 (95.9) |

| Baccalaureate program (four-year program in nursing) or masters’ program in nursing | 21 (3.7) |

| Items | No. a (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic work motivation | 1. Community medicine | 56 (10.0) |

| 2. The practice of basic nursing | 73 (13.0) | |

| 3. Gerontological nursing | 230 (41.0) | |

| 4. Careful nursing care | 113 (20.1) | |

| Extrinsic work motivation | 5. Be transferred by the corporation | 74 (13.2) |

| 6. Recommended by acquaintances | 115 (20.5) | |

| 7. Attracted by the convenient location and transportation | 215 (38.3) | |

| 8. Attracted by the working conditions | 155 (27.6) | |

| Total Number of Items Selected | No. (%) (Intrinsic Work Motivation) | No. (%) (Extrinsic Work Motivation) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 250 (44.6) | 136 (24.2) |

| 1 | 188 (33.5) | 294 (52.4) |

| 2 | 89 (15.9) | 129 (23) |

| 3 | 30 (5.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| 4 | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) |

| Total | 561 (100) | 561 (100) |

| N | Min | Max | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work engagement | 561 | 0 | 6 | 2.98 | 0.98 |

| Individual Attributes | β | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.104 | * | 1.17 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.001 | 0.969 | 1.049 |

| Educational background | 0.062 | 0.111 | 1.031 |

| Marital status (Married) | −0.040 | 0.368 | 1.346 |

| Number of children (1+) | 0.095 | * | 1.400 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.375 | ** | 1.055 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 0.164 | ** | 1.129 |

| Extrinsic motivation | −0.02 | 0.617 | 1.077 |

| Years working at the current facility | 0.001 | 0.972 | 1.108 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, D.; Takada, N.; Hara, Y.; Sugiyama, S.; Ito, Y.; Nihei, Y.; Asakura, K. Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nurses Working in Long-Term Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031284

Zeng D, Takada N, Hara Y, Sugiyama S, Ito Y, Nihei Y, Asakura K. Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nurses Working in Long-Term Care Facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031284

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Derong, Nozomu Takada, Yukari Hara, Shoko Sugiyama, Yoshimi Ito, Yoko Nihei, and Kyoko Asakura. 2022. "Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nurses Working in Long-Term Care Facilities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031284