Bridging the Knowledge Gap for Pressure Injury Management in Nursing Homes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Phase 1: Framework Composition to Enhance the Performance of Caring for Pressure Injuries in Nursing Homes

2.2.1. Problem Identification

2.2.2. Adapting Knowledge to the Local Context

2.2.3. Assessing Barriers to Knowledge Use

2.3. Phase 2: Development of Educational Program Based on the Configured Framework and Verification of Effectiveness

2.3.1. Selection, Tailoring, and Implementation of Interventions

2.3.2. Monitoring Knowledge Use, Evaluating Outcomes, and Sustaining Knowledge Use

- (1)

- Participants

- (2)

- Procedure

- (3)

- Outcome measures

- (4)

- Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Composition of the Framework to Enhance the Performance of Pressure Injury Management in Nursing Homes

3.1.1. Unexpected Wound Healing Process: Integrated Thinking

“I tried the products I received as a sample from the training before, but they did not work. Thus, when I asked, they said that it was difficult to see good effects on residents who are in poor condition.”

“Despite knowing that prevention is paramount for pressure injuries, there are too many other major problems for older people. Pressure injuries are often not even listed among the priorities because the elderly have many life-threatening problems, such as when a resident has a breathing problem and has to remain in a position that causes pressure injuries, knowing that it would cause pressure injuries.”

“There are times when things go wrong, particularly when I am obsessed with a product that was recommended for use by the hospital, thinking that it is the only answer. However, if something does not feel right, it is better to reassess from the beginning to make a judgment or ask for help. I think it is important to re-think the whole thing according to that specific pressure injury and the resident’s condition on that day.”

3.1.2. Restrictive Situation: Understanding in an Environmental Context

“I believe most of the nurses in the facility have some knowledge. However, unusual cases also do occur. Occasionally, unusual cases occur depending on the resident’s degree of contraction and mobility.”

“I received education on pressure injury management, but not all the products I learned about at that time are available at the facility.”

“Not only do residents have diverse economic conditions but if the resident’s condition, for example, is near the end of the life cycle, there are cases in which a low-cost product is preferred over a high-priced product. In that case, you need to know about the various items that can be used as an alternative.”

“Residents who have dementia may have problem behaviors, and the medications they take may cause them to spend more time in bed. In that’s the case, although they are not in the high-risk group for pressure injuries, pressure injuries may develop.”

3.1.3. Confusion in the Access System: Interpersonal Relationships for Efficient Decision-Making

“Even if we explain the resident’s pressure injuries well to the caregiver, there are cases where continuous care cannot be provided when a different caregiver comes later. If communication with the caregiver is not effective, pressure injuries cannot be treated properly.”

“I asked for pressure to not be applied on pressure injuries while the resident is in physical therapy, but this was not well communicated, and there were times when pressure was applied.”

“Sometimes residents need to go to the hospital for pressure injury treatment. In these cases, written information is received, but the caregiver is responsible for relaying the information from the hospital accurately; treatment is difficult when this is not done.”

“Nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and nutritionists all get together and have a meeting about pressure injuries once a week. Based on the results, if each of us put in the effort, such as performing physical therapy while avoiding the area with pressure injuries as much as possible, or preparing nutritious food for healing, good results were obtained.”

3.1.4. Unstable Support System: Meeting any Challenges to Professional Development

“Each nurse at our facility has a highly varying degree of competence. However, even the assessment of pressure injuries can sometimes be incorrect when assessing the same pressure injury, and it is challenging for us to perform interventions accordingly.”

“As we do not have a doctor specializing in wound healing, nurses often have to make decisions themselves, leaving us feeling anxious.”

“As there are a variety of professions working together at the facility, it is necessary to consider pressure injury management as something important and have the ability to motivate everyone involved. Not only knowledge but responsibility, attitude, and attention are the keys to success.”

“I met with a wound specialist at a nearby teaching hospital and kept in contact with them and asked for advice. Nonetheless, because the environment is different, we cannot apply it as-is. Still, we are working hard to establish a connection by applying the best possible method in our facility and sending residents to a hospital for treatment if necessary.”

3.2. Phase 2: Development of the Educational Program Based on the Configured Frame and Verification of Effectiveness

3.2.1. Prior Homogeneity Verification of Subjects’ General Characteristics and Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Verification of the Effectiveness of the Education Program

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Heo, S.; Hong, S.W.; Shim, J.; Lee, J.A. Correlates of advance directive treatment preferences among community-dwelling older people with chronic diseases. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Jin, X.; Liu, C.; Jin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, S.; Tang, H.; Yan, J. Investigating the prevalence of dementia and its associated risk factors in a Chinese nursing home. J. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 13, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailie, R.; Matthews, V.; Larkins, S.; Thompson, S.; Burgess, P.; Weeramanthri, T.; Bailie, J.; Cunningham, F.; Kwedza, R.; Clark, L. Impact of policy support on uptake of evidence-based continuous quality improvement activities and the quality of care for Indigenous Australians: A comparative case study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.T. Quality long-term care for older people: A commentary. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 618–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranley, L.A.; Hoben, M.; Yeung, J.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Norton, P.G.; Wagg, A. SCOPEOUT: Sustainability and spread of quality improvement activities in long-term care-a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuwahara, M.; Tada, H.; Mashiba, K.; Yurugi, S.; Iioka, H.; Niitsuma, K.; Yasuda, Y. Mortality and recurrence rate after pressure ulcer operation for elderly long-term bedridden patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2005, 54, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, E.W.Y.; Pang, S.M.C.; Aboo, G.H.; Law, S.S.M. Pressure ulcer development in older residents in nursing homes: Influencing factors. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 2608–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellefield, M.E. Prevalence rate of pressure ulcers in California nursing homes: Using the OSCAR database to develop a risk-adjustment model. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2004, 30, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, D.; Rubenstein, L.V.; Simon, B.; Hickey, E.; Ferrell, B.; Czarnowski, E.; Berlowitz, D. Adherence to pressure ulcer prevention guidelines: Implications for nursing home quality. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, W.L.; Pimentel, C.B.; Snow, A.L.; Allen, R.S.; Wewiorski, N.J.; Palmer, J.A.; Clark, V.; Roland, T.M.; McDannold, S.E.; Hartmann, C.W. Nursing home staff perceptions of barriers and facilitators to implementing a quality improvement intervention. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, R.R.; Gifford, D.R.; Lyder, C.H.; Schall, M.W.; Funston-Dillon, D.L.; Lewis, J.M.; Ordin, D.L. Quality improvement for pressure ulcer care in the nursing home setting: The Northeast Pressure Ulcer Project. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2003, 4, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.E.; White, J.; Fairchild, T.J. Ineffective staff, ineffective supervision, or ineffective administration? Why some nursing homes fail to provide adequate care. Gerontologist 1992, 32, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavallée, J.F.; Gray, T.A.; Dumville, J.; Cullum, N. Barriers and facilitators to preventing pressure ulcers in nursing home residents: A qualitative analysis informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, A.; Yu, H.; Grabowski, D.C. High Nursing Staff Turnover in Nursing Homes Offers Important Quality Information: Study examines high turnover of nursing staff at US nursing homes. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wipke-Tevis, D.D.; Williams, D.A.; Rantz, M.J.; Popejoy, L.L.; Madsen, R.W.; Petroski, G.F.; Vogelsmeier, A.A. Nursing home quality and pressure ulcer prevention and management practices. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herck, P.; Sermeus, W.; Jylha, V.; Michiels, D.; Van Den Heede, K. Using hospital administrative data to evaluate the knowledge-to-action gap in pressure ulcer preventive care. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2009, 15, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnyu, K.J.; McCleary, N.; Presseau, J.; Ivers, N.M.; Grimshaw, J.M. Behavior change techniques in continuing professional development. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2020, 40, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, I.D.; Logan, J.; Harrison, M.B.; Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Caswell, W.; Robinson, N. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2006, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, I.D.; Tetroe, J.M. The knowledge to action framework. In Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: Linking Evidence to Action; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Stemler, S. An overview of content analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2000, 7, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett, T. Consensus-Oriented Decision-Making: The CODM Model for Facilitating Groups to Widespread Agreement; New Society Publishers: British Columbia, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analyzing Qualitative Data; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002; pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, O.K. Effectiveness of Case-Centered Education Program based on Nursing Protocol for Pressure Injury Stages. Ph.D. Thesis, Korea University, Seoul, Korea, 2018. in press.

- Pieper, B.; Zulkowski, K. The Pieper-Zulkowski pressure ulcer knowledge test. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2014, 27, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeckman, D.; Vanderwee, K.; Demarré, L.; Paquay, L.; Van Hecke, A.; Defloor, T. Pressure ulcer prevention: Development and psychometric validation of a knowledge assessment instrument. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J. The development and effectiveness of blended-learning program of pressure ulcer management. Ph.D. Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, 2014. in press.

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Korean Association of Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses. Effects of pressure ulcer classification system education programme on knowledge and visual differential diagnostic ability of pressure ulcer classification and incontinence-associated dermatitis for clinical nurses in Korea. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lasater, K. Clinical judgment development: Using simulation to create an assessment rubric. J. Nurs. Educ. 2007, 46, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gunningberg, L. Pressure ulcer prevention: Evaluation of an education programme for Swedish nurses. J. Wound Care 2004, 13, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Armstrong, A.P.; Moore, Z.E.; Bradbury, I.; McDonough, S. Education of healthcare professionals for preventing pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.K.; Karadag, A. Assessment of nurses’ knowledge and practice in prevention and management of deep tissue injury and stage I pressure ulcer. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2010, 37, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Roche, S.; Van Wynen, E. The effects of various instructional methods on retention of knowledge about pressure ulcers among critical care and medical-surgical nurses. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2011, 42, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.J. A study on the nursing knowledge, attitude, and performance towards pressure ulcer prevention among nurses in Korea long-term care facilities. Int. Wound J. 2019, 16, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, T.-C.; Luk, J.K.-H.; Chu, L.-W.; Chan, F.H.-W. Low education level of nursing home staff in Chinese nursing homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 849–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-C.; Kao, H.-F.S.; Liu, H.-C.; Liang, H.-F.; Chu, T.-P.; Lee, B.-O. Effects of simulation-based learning on nursing students’ perceived competence, self-efficacy, and learning satisfaction: A repeat measurement method. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 97, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components of KTA Model | Methods Used to Address Component in This Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Study Method | Objective | |

| A total of 10 nurses at a nursing home | In-depth interview | Identification of composition and problems of pressure injury management knowledge at nursing homes |

| Six current working nurses at a nursing home | CODM | To design a practical education framework suitable for pressure injury management in nursing homes, we agreed on a strategy and education composition for pressure injury management in nursing homes. |

| Five current workers at a nursing home and five wound nurses | Content Validity Index (CVI) | Barriers and facilitating factors were identified through content validity verification. |

| Two researchers and one computer program developer | Program development | We developed a web-based pressure injury management educational program for nurses in nursing homes. |

| A total of 35 nurses at nursing homes (17 nurses in the experimental group, 18 nurses in the control group) | Study design with randomizedexperimental and control group | Tests were conducted for nurses in nursing homes on their knowledge, attitude, pressure injury stage identification ability, and the ability for clinical judgment on pressure injury management. |

| After 4 weeks of intervention, the same test was conducted to confirm continuity. | ||

| Problems Identified | Adapting Knowledge to the Local Context/ Assessing Barriers to Knowledge Use | Implementation in an Education Program | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpredictable wound healing process | Limitations of generic pressure injury education based on the normal healing process | Integrated thinking | Integrated approach of evidence-based knowledge and experience | Enhance educational content based on the guidelines |

| Problems of diseases with higher priorities than pressure injuries | Re-think and revise by comparing expected effects with the outcome | |||

| Restrictive situations | Characteristics of residents vulnerable to pressure injuries | Understanding in environmental contexts | Understanding the characteristics of residents | Case-based education |

| Limited resources at nursing homes | Understanding the available resources | |||

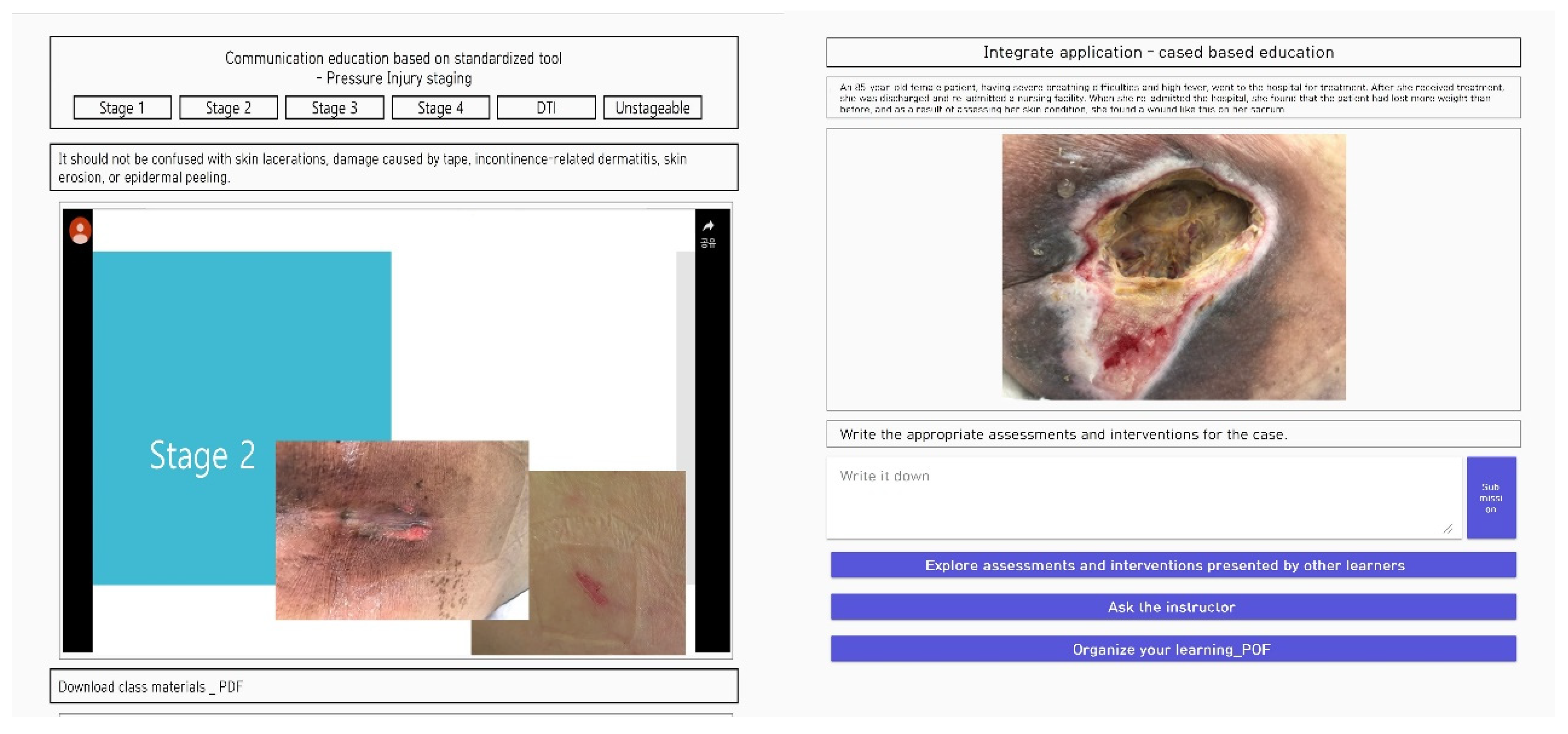

| Confusion in the access system | Variability in the person deciding for the resident | Interpersonal relationships for efficient decision making | Build a multidisciplinary collaboration system | Communication education based on standardized tools |

| Lack of organized system | Effective communication with residents and caregivers | |||

| Unstable support system | Limited personnel and frequent turnover | Meeting any challenges to professional development | Exploring individual competency in pressure injury management | Introduction accessible network |

| Lack of personnel to provide professional knowledge | Willingness to improve systemic pressure injury management | |||

| Variables | Time | Exp. | Cont | Source | F (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD ± SD | MD ± SD | ||||

| Pressure injury nursing knowledge | Pre-test | 26.12 ± 3.35 | 25.72 ± 5.00 | Group | 4.43 (0.04) |

| Post-test | 29.76 ± 4.58 | 26.50 ± 4.59 | Time | 15.89 (<0.001) | |

| Follow up | 31.41 ± 3.79 | 27.89 ± 2.45 | GxT | 3.40 (0.04) | |

| Pressure injury Nursing attitude | Pre-test | 35.00 ± 4.85 | 35.72 ± 2.54 | Group | 0.85 (0.36) |

| Post-test | 36.39 ± 5.63 | 36.06 ± 4.12 | Time | 10.19 (<0.001) | |

| Follow up | 40.47 ± 2.94 | 36.94 ± 4.29 | GxT | 4.15 (0.02) | |

| Ability to identify pressure injury stages | Pre-test | 9.94 ± 3.94 | 10.17 ± 4.12 | Group | 4.43 (0.04) |

| Post-test | 13.76 ± 2.99 | 10.83 ± 3.09 | Time | 30.65 (<0.001) | |

| Follow up | 15.47 ± 2.81 | 11.83 ± 2.98 | GxT | 9.81 (<0.001) | |

| Clinical judgment on pressure injury management | Pre-test | 23.82 ± 2.70 | 24.00 ± 3.12 | Group | 7.30 (0.01) |

| Post-test | 27.18 ± 2.30 | 25.56 ± 2.59 | Time | 32.20 (<0.001) | |

| Follow up | 30.65 ± 3.00 | 25.94 ± 3.62 | GxT | 10.15 (<0.001) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.-N.; Kwon, D.-Y.; Chang, S.-O. Bridging the Knowledge Gap for Pressure Injury Management in Nursing Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031400

Lee Y-N, Kwon D-Y, Chang S-O. Bridging the Knowledge Gap for Pressure Injury Management in Nursing Homes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031400

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ye-Na, Dai-Young Kwon, and Sung-Ok Chang. 2022. "Bridging the Knowledge Gap for Pressure Injury Management in Nursing Homes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031400

APA StyleLee, Y.-N., Kwon, D.-Y., & Chang, S.-O. (2022). Bridging the Knowledge Gap for Pressure Injury Management in Nursing Homes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031400