Research Priorities of Applying Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensors in Southeast Asian Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Publications on Source Evaluation in SEA Using LCPMS

3.1.1. Biomass and Agriculture Burning

3.1.2. Transportation

3.1.3. Asian-Style Cooking and Street Cooking

3.1.4. Incense Burning

3.1.5. Open Waste Burning

3.1.6. Fuel Combustion for Brick Manufacturing

3.2. Publications on Ambient Monitoring and Transport in SEA Using LCPMS

3.2.1. Ambient PM2.5 Levels in the Eight Countries Using LCPMS

3.2.2. LCPMS Networks in SEA

3.3. Publications on Exposure Assessment in SEA Using LCPMS

3.3.1. The 24-h Personal PM2.5 Exposure

3.3.2. Activities Associated with Peak PM2.5 Exposures

3.4. Publications on Exposure–Health Evaluations in SEA Using LCPMS

3.4.1. Exposure–Health Evaluation for the General Public

3.4.2. Exposure–Health Evaluation of High-Exposure or Susceptible Subpopulations

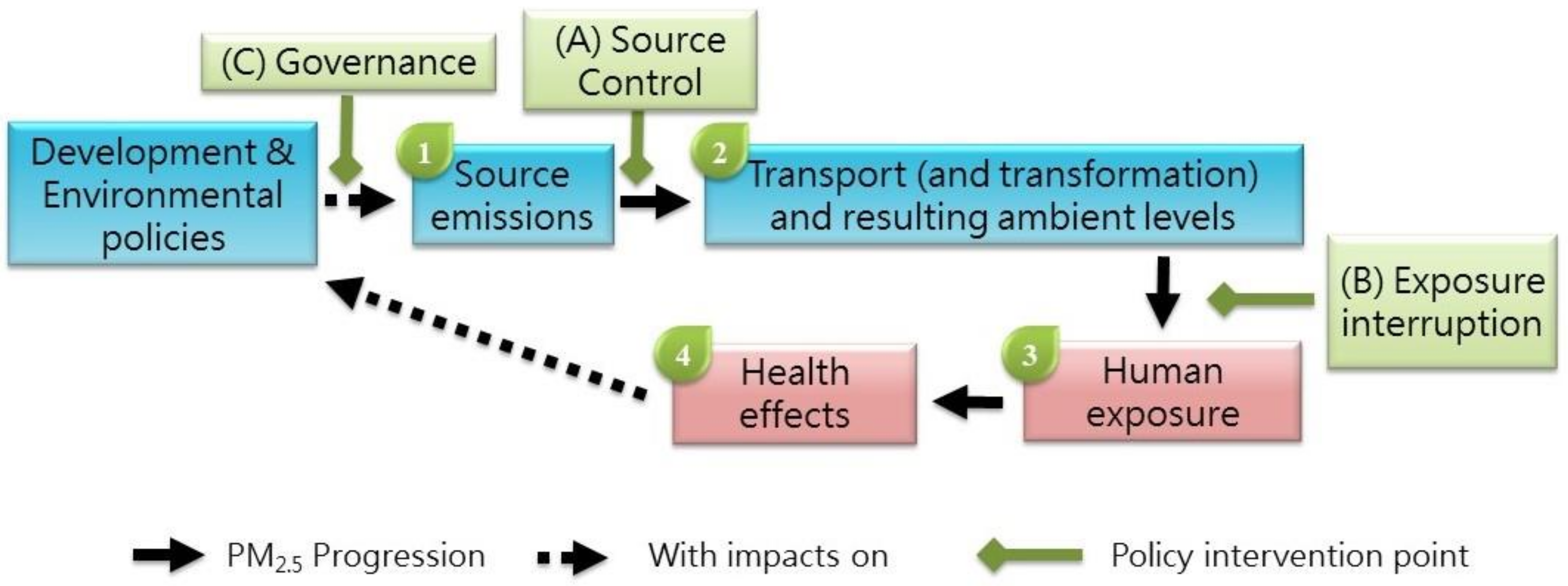

3.5. Research Gaps That Can Be Filled in SEA with LCPMS Applications

- What are the source characteristics of the distinctive Asian sources that have been understudied? What are the key factors associated with the sources’ strength?

- What are the temporospatial variations of ambient PM2.5 levels in densely populated areas without monitoring stations? What are the peak PM2.5 levels in hot spots within communities that may result in the high exposure of residents?

- What are the peak PM2.5 exposure levels and patterns of the SEA population, especially in high-exposure or susceptible subpopulations? What are the sources, activities, and associated controllable factors causing peak PM2.5 exposures?

- What are the damage coefficients of the exposure–health relationship for respiratory and cardiovascular health outcomes due to peak PM2.5 exposures? Are the damage coefficients for the same health outcome different at different PM2.5 concentration ranges?

- Should there be a ceiling value or short-term standard for PM2.5 (e.g., 8 h or hourly)? What other considerations need to be included to promote the establishment of such a standard?

4. Discussion

4.1. Unique Angles and Contribution to the International Research Community

- There are distinctive PM2.5 sources in SEA, such as outdated practices (e.g., open waste burning, fuel combustion for brick manufacturing), different locally made vehicles (motorcycles, jeepney, tuk-tuks, or others), different types of open biomass burning (forest, peat, rice straw, sugar cane, etc.), different cooking practices (stir-frying, deep-frying, etc.) using a range of solid fuels, and different culture-related activities (incense burning with incense made from different materials) that may cause high PM2.5 concentrations in the ambient air and high PM2.5 exposures to residents or workers. An international comparison of source characteristics and exposure patterns related to those sources with LCPMS presents a more comprehensive overview of the PM2.5 emission features of those sources. These findings can improve emissions inventories and facilitate the improvement of PM2.5 modeling and assist in prioritizing the control strategies of the authorities. The improvement of regional emissions inventories will also be beneficial to regional and global aerosol modeling as well as climate modeling, since aerosols have direct and indirect impacts on climate change [131].

- Episodes due to the regional transport of large-scale open biomass burning impact the source and downwind countries, making this an important international issue in SEA. LCPMS installed in different countries with spatial coverage wider than the standard EPA stations provide more details showing the actual affected levels, areas, and populations. LCPMS networks can provide PM2.5 at ground level, where people live, which is superior to remote-sensing images showing aerosol loadings for the whole vertical column. After all, those transported aerosols in altitudes higher than 1000 m may affect visibility but not affect the PM2.5 exposure and health of local residents. Thus, from a public health point of view, setting LCPMS networks in SEA is the best way of providing scientific evidence for international negotiations dealing with regional biomass burning. Moreover, early warning systems based on LCPMS networks could be a powerful policy tool, enabling authorities to have quick responsive actions and enhance the self-protection of the general public. This can further serve as an example for African countries to warn about dust storms.

- Using newly developed LCPMS and bio-sensors with coherence methodology, PM2.5 damage coefficients can be obtained for different subpopulations in different SEA countries. Comparing PM2.5 health damage coefficients of the same health outcome across different countries with different PM2.5 exposure levels can provide insightful knowledge on PM2.5 health impacts; this is a fascinating and challenging question and cannot be answered in Western countries with low PM2.5. A meta-analysis of the studies conducted in different countries can also support more effective science–policy communication in this region as a whole. The synthesis of these findings can provide policy-relevant recommendations for SEA countries and beyond to reduce PM2.5 exposure and health risks wherever needed.

- Weather patterns in SEA are controlled by the Asian monsoon, which results in significantly different PM2.5 levels within a country, i.e., lower PM2.5 in rainy seasons and higher PM2.5 in dry seasons. On the other hand, under climate change, SEA countries have also experienced more frequent heat waves with extreme temperatures. Both temperature and relative humidity affect human heat stress, which leads to cardiovascular impacts [132]; these weather parameters are confounders of PM2.5 health impacts. Currently, certain LCPMS devices, such as AS-LUNG, are equipped with low-cost temperature and humidity sensors to collect PM2.5, temperature, and relative humidity simultaneously with a resolution of 15 s, 1 min, or 5 min to evaluate health impacts of PM2.5 and weather parameters altogether. Thus, conducting panel epidemiological studies in SEA with LCPMS provides a unique opportunity to assess the synergistic effects of PM2.5 (varied in different countries) and heat stress under humid versus dry conditions on cardiovascular functions. Understanding this synergistic effect provides insights into the physiological reactions of human bodies responding to environmental changes. The research findings are particularly valuable under the trend of climate change, since other countries may soon experience heat stress and PM2.5 altogether.

4.2. Challenges in LCPMS Application

4.3. Transdisciplinary Perspectives and Stakeholder Engagement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Research Region | Participant | Affiliation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Australia | Fabienne REISEN | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) Oceans and Atmosphere/Climate Science Centre |

| 2 | Bangladesh | Mahbuba YESMIN | Internal Medicine Department, Apollo Hospital, Dhaka |

| 3 | Bangladesh | Abdus SALAM | Department of Chemistry, University of Dhaka |

| 4 | India | Swastik BHARDWAJ | All India Institute of Medical Sciences Bhopal |

| 5 | India | Harshita PAWAR | Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Mohali |

| 6 | Indonesia | Ir. Puji LESTARI | Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Institute of Technology Bandung |

| 7 | Indonesia | Dwi AGUSTIAN | Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Dept. of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran |

| 8 | Japan | Giles Bruno SIOEN | Future Earth Global Hub—Japan |

| 9 | Japan | Hein MALLEE | Regional Centre for Future Earth in Asia; Research Institute for Humanity and Nature |

| 10 | Japan | Hiroshi TANIMOTO | International Global Atmospheric Chemistry (IGAC); National Institute for Environmental Studies |

| 11 | Japan | Tatsuya NAGASHIMA | Regional Atmospheric Modeling Section, Center for Regional Environment Research, National Institute for Environmental Studies |

| 12 | Japan | Lina MADANIYAZI | Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Nagasaki University |

| 13 | Korea | Kiyoung LEE | Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University |

| 14 | Korea | Sooyoung GUAK | Environmental Health, School of Public Health, Seoul National University |

| 15 | Malaysia | Mohd Talib LATIF | School of Environmental and Natural Resource Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

| 16 | Malaysia | Mazrura SAHANI | Center for Health and Applied Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

| 17 | Malaysia | Mohd Nordin HASAN | Regional Centre for Future Earth in Asia |

| 18 | Myanmar | Ohnmar May Tin HLAING | Environmental Health Consultant Environmental Quality Management Co., Ltd. |

| 19 | Nepal | Yadav Prasad JOSHI | Environmental Health and Occupational Health, Manmohan Memorial Institute of Health Sciences |

| 20 | Pakistan | Muhammad Fahim KHOKHAR (On-Line) | Institute of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, National University of Sciences and Technology |

| 21 | Pakistan | Ejaz Ahmad KHAN (On-Line) | Health Services Academy |

| 22 | Philippines | Maria Obiminda L. CAMBALIZA | Department of Physics, Ateneo de Manila University/Air Quality Dynamics Laboratory, Manila Observatory |

| 23 | Philippines | John Q. WONG | Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health, Ateneo de Manila University |

| 24 | Taiwan | Wen-Cheng WANG | Research Center for Environmental Change, Academia Sinica |

| 25 | Taiwan | Shih-Chun Candice LUNG | Research Center for Environmental Changes, Academia Sinica |

| 26 | Thailand | Nguyen Thi Kim OANH | Environmental Engineering and Management, Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) |

| 27 | Thailand | Kraichat TANTRAKARNAPA | Department of Social and Environmental Medicine, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University |

| 28 | Vietnam | To THI HIEN | University of Science, Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City |

| 29 | Vietnam | Tran Ngoc DANG | Environmental Health Department, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh City |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Who Global Air Quality Guidelines. Particulate Matter (Pm2.5 and Pm10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. WHO. 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345329 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). One Third of Global Air Pollution Deaths in Asia Pacific. WHO. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/news/detail/02-05-2018-one-third-of-global-air-pollution-deaths-in-asia-pacific (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Alfano, B.; Barretta, L.; del Giudice, A.; de Vito, S.; di Francia, G.; Esposito, E.; Formisano, F.; Massera, E.; Miglietta, M.L.; Polichetti, T. A Review of Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors from the Depvelopers’ Perspectives. Sensors 2020, 20, 6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovašević-Stojanović, M.; Bartonova, A.; Topalović, D.; Lazović, I.; Pokrić, B.; Ristovski, Z. On the use of small and cheaper sensors and devices for indicative citizen-based monitoring of respirable particulate matter. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 206, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, J.; Dutta, M.; Marques, G. Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Systems Based on Internet of Things: A systematic review. Int J Public Health 2020, 17, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L. Calibrating low-cost sensors for ambient air monitoring: Techniques, trends, and challenges. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lung, S.C.C.; Tsou, M.C.M.; Hu, S.C.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Wang, W.C.V.; Shui, C.K.; Tan, C.H. Concurrent assessment of personal, indoor, and outdoor PM2.5 and PM1 levels and source contributions using novel low-cost sensing devices. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akther, T.; Ahmed, M.; Shohel, M.; Ferdousi, F.K.; Salam, A. Particulate matters and gaseous pollutants in indoor environment and Association of ultra-fine particulate matters (PM1) with lung function. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 5475–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, S.C.C.; Wang, W.C.V.; Wen, T.Y.J.; Liu, C.H.; Hu, S.C. A versatile low-cost sensing device for assessing PM2.5 spatiotemporal variation and quantifying source contribution. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 137145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IQAir Group. World Air Quality Report 2020, Region & City PM2.5 Ranking. Available online: https://www.iqair.com/world-most-polluted-cities/world-air-quality-report-2020-en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Ebi, K.L.; Harris, F.; Sioen, G.B.; Wannous, C.; Anyamba, A.; Bi, P.; Boeckmann, M.; Bowen, K.; Cissé, G.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Transdisciplinary research priorities for human and planetary health in the context of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 17, 8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, D.; Setyawati, W.; Cheng, F.Y.; Lung, S.C.C. Investigation on daily exposure to PM2.5 in Bandung City, Indonesia using low-cost sensor. J Expo. Sci Environ. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, S.C.C.; Chen, N.; Hwang, J.S.; Hu, S.C.; Wang, W.C.V.; Wen, T.Y.J.; Liu, C.H. Panel study using novel sensing devices to assess associations of PM2.5 with heart rate variability and exposure sources. J. Expo. Sci Environ. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, M.C.M.; Lung, S.C.C.; Shen, Y.S.; Liu, C.H.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Chen, N.; Hwang, J.S. A community-based study on associations between PM2.5 and PM1 exposure and heart rate variability using wearable low-cost sensing devices. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, United Nations. Total Population—Both Sexes. 2019. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/population (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- United Nations. United Nations Statistic Division. 2007. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/environment/totalarea.htm (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- The World Bank. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Per Capita in Current USD, World Bank. 2021. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- International Labour Organization. Employment in Agriculture, Industry, Services and Unemployment: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Republic of China, National Statistics. Available online: https://statdb.dgbas.gov.tw/pxweb/Dialog/statfile9L.asp (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Republic of China, National Statistics, Employment of Taiwan. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=44241&ctNode=543 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- IQAir Group. World Air Quality Report 2019. Available online: https://www.iqair.com/world-most-polluted-cities/world-air-quality-report-2019-en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- World City Populations 2021. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- BPS-Statistical center of DKI Jakarta Province. DKI Jakarta Province in Figures. 2020. Available online: https://jakarta.bps.go.id/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal (DOSM). 2020. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/ (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Highlights of the National Capital Region (NCR) Population 2020 Census of Population and Housing, (CPH). 2021. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-national-capital-region-ncr-population-2020-census-population-and-housing-2020 (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Dept. of Household Registration, Ministry of the Interior. Republic of China (Taiwan). Available online: https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bangkok Data Source. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/22617/bangkok/population (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- The General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam 2019; Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2019; p. 97.

- Wang, W.C.V.; Lung, S.C.C.; Liu, C.H.; Shui, C.K. Laboratory evaluations of correction equations with multiple choices for seed low-cost particle sensing devices in sensor networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.T.; Othman, M.; Idris, N.; Juneng, L.; Abdullah, A.M.; Hamzah, W.P.; Khan, M.F.; Nik Sulaiman, N.M.; Jewaratnam, J.; Aghamohammadi, N.; et al. Impact of regional haze towards air quality in Malaysia: A review. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 177, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Oanh, N.T.; Permadi, D.A.; Hopke, P.K.; Smith, K.R.; Dong, N.P.; Dang, A.N. Annual emissions of air toxics emitted from crop residue open burning in Southeast Asia over the period of 2010–2015. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 187, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, B.T.; Matsumi, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kajii, Y.; Nghiem, T.D. Characterizing PM2.5 in hanoi with new high temporal resolution sensor. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 2487–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, B.-T.; Matsumi, Y.; Vu, T.V.; Sekiguchi, K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, C.T.; Nghiem, T.D.; Ngo, I.-H.; Kurotsuchi, Y.; Nguyen, T.-H.; et al. The effects of meteorological conditions and long-range transport on PM2.5 levels in Hanoi revealed from multi-site measurement using compact sensors and machine learning approach. J. Aerosol Sci. 2021, 152, 105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanabkaew, T.; Mekbungwan, P.; Raksakietisak, S.; Kanchanasut, K. Detection of PM2.5 plume movement from IoT ground level monitoring data. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Choudhary, S.; Raliya, R.; Chadha, T.S.; Fang, J.; George, M.P.; Biswas, P. Deployment of networked low-cost sensors and comparison to real-time stationary monitors in New Delhi. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulong, N.A.; Latif, M.T.; Khan, M.F.; Amil, N.; Ashfold, M.J.; Wahab, M.I.A.; Chan, K.M.; Sahani, M. Source apportionment and health risk assessment among specific age groups during haze and non-haze episodes in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601–602, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtar, A.A.A.; Latif, M.T.; Baharudin, N.H.; Ahamad, F.; Chung, J.X.; Othman, M.; Juneng, L. Variation of major air pollutants in different seasonal conditions in an urban environment in Malaysia. Geosci. Lett. 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamkaew, C.; Chantara, S.; Janta, R.; Pani, S.K.; Prapamontol, T.; Kawichai, S.; Wiriya, W.; Lin, N.H. Investigation of biomass burning chemical components over Northern Southeast Asia during 7-SEAS/BASELInE 2014 Campaign. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, J.; Ohara, T. Long-term historical trends in air pollutant emissions in Asia: Regional emission inventory in ASia (REAS) version 3. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 12761–12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, N.A.H.; Hoek, G.; Simic-Lawson, M.; Fischer, P.; van Bree, L.; ten Brink, H.; Keuken, M.; Atkinson, R.W.; Anderson, H.R.; Brunekreef, B.; et al. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lestari, P.; Damayanti, S.; Arrohman, M.K. Emission inventory of pollutants (CO, SO2, PM2.5, and NOx) in Jakarta, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 489, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha Chi, N.N.; Kim Oanh, N.T. Photochemical smog modeling of PM2.5 for assessment of associated health impacts in crowded urban area of Southeast Asia. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources Environmental Management Bureau (DENR—EMB, Philippines). National Air Quality Status Report 2008–2015. 2015. Available online: https://emb.gov.ph/national-air-quality-status-report/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Madueño, L.; Kecorius, S.; Birmili, W.; Müller, T.; Simpas, J.; Vallar, E.; Galvez, M.C.; Cayetano, M.; Wiedensohler, A. Aerosol particle and black carbon emission factors of vehicular fleet in Manila, Philippines. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jinsart, W.; Kaewmanee, C.; Inoue, M.; Hara, K.; Hasegawa, S.; Karita, K.; Tamura, K.; Yano, E. Driver exposure to particulate matter in Bangkok. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2012, 62, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snyder, E.G.; Watkins, T.H.; Solomon, P.A.; Thoma, E.D.; Williams, R.W.; Hagler, G.S.W.; Shelow, D.; Hindin, D.A.; Kilaru, V.J.; Preuss, P.W. The Changing Paradigm of Air Pollution Monitoring. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11369–11377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.V.; Lin, T.H.; Liu, C.H.; Su, C.W.; Lung, S.C.C. Fusion of environmental sensing on PM2.5 and deep learning on vehicle detecting for acquiring roadside PM2.5 concentration increments. Sensors 2020, 20, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva Nagendra, S.M.; Yasa, P.R.; Narayana, M.V.; Khadirnaikar, S.; Rani, P. Mobile monitoring of air pollution using low cost sensors to visualize spatio-temporal variation of pollutants at urban hotspots. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 44, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.S.; Vanajakshi, L.D. Analysis of the Near-road Fine Particulate Exposure to Pedestrians at Varying Heights. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 210104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Chang, C.T.; Ma, C.M. Simulation and measurement of air quality in the traffic congestion area. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2021, 31, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Household Air Pollution and Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- McCarron, A.; Uny, I.; Caes, L.; Lucas, S.E.; Semple, S.; Ardrey, J.; Price, H. Solid fuel users’ perceptions of household solid fuel use in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huy, L.N.; Winijkul, E.; Kim Oanh, N.T. Assessment of emissions from residential combustion in Southeast Asia and implications for climate forcing potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Park, H.; Seo, Y.; Yun, J.; Kwon, J.; Park, K.W.; Han, S.-B.; Oh, K.C.; Jeon, J.M.; Cho, K.S. Emission characteristics of particulate matter, odors, and volatile organic compounds from the grilling of pork. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.C.; Su, H.J. Chemical and stable isotopic characteristics of PM2.5 emitted from Chinese cooking. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, B.A. Risk factors in street food practices in developing countries: A review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2016, 5, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.W.; Vo, T.T.T.; Wee, Y.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Chi, M.C.; Chen, M.L.; Hsu, L.F.; Fang, M.L.; Lee, K.H.; Guo, S.-E.; et al. The Adverse impact of incense smoke on human health: From mechanisms to implications. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 5451–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mattewal, S.K.; Patel, S.; Biswas, P. Evaluation of nine low-cost-sensor-based particulate matter monitors. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, L.K.; Morawska, L.; Quang, T.N.; Jayaratne, R.E.; Hue, N.T.; Dat, M.V.; Phi, T.H.; Thai, P.K. The impact of incense burning on indoor PM2.5 concentrations in residential houses in Hanoi, Vietnam. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Waste Not: The Heavy Toll of Our Trash. Story Chemicals & Pollution Action, 7 September 2020. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/waste-not-heavy-toll-our-trash (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- The World Bank Group. What A Waste 2.0. A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. 2018. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Pansuk, J.; Junpen, A.; Garivait, S. Assessment of Air Pollution from Household Solid Waste Open Burning in Thailand. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim Oanh, N.T.; Monitoring and Inventory of Hazardous Pollutants Emissions from Solid Waste Open Burning. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2017, Abstract #A43A-2418. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017AGUFM.A43A2418K/abstract (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Huy, L.N.; Winijkul, E.; Oanh, N.T.K. Emission inventory of air toxic pollutants from household solid waste open burning in Vietnam. In Proceedings of the 19th GEIA Conference, Santiago, Chile, 6–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmar, M.T.H. Strengthening Evidence for Action: Impacts of Open Waste Burning in Mandalay, Asia Pacific Clean Air Partnership (UN Environment), Newsletter Issue 9. 2020. Available online: https://cleanairsolutions.asia/wp-content/uploads/APCAP-Newsletter-Issue-9-November-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Yi, E.E.P.; Nway, N.C.; Aung, W.Y.; Thant, Z.; Wai, T.H.; Hlaing, K.K.; Maung, C.; Yagishita, M.; Ishigaki, Y.; Win-Shwe, T.T.; et al. Preliminary monitoring of concentration of particulate matter (PM2.5) in seven townships of Yangon City, Myanmar. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2018, 23, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, B.A.; Biswas, S.K.; Hopke, P.K. Key issues in controlling air pollutants in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 7705–7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.A.; Oanh, N.T.K. Integrated assessment of brick kiln emission impacts on air quality. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 171, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, S.; Sivertsen, B.; Ahammad, S.S.; Cruz, N.D.; Dam, V.T. Emissions Inventory for Dhaka and Chittagong of Pollutants PM10, PM2.5, NOx, SOx, and CO; Contribution of Brick Kilns to Air Quality in Dhaka City; Bottom-Up-Emission Inventory and Dispersion Modelling; Norwegian Institute for Air Research-NILU OR: Kjeller, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, D.P.; Chaudhary, S.; Shakya, R.; Sah, P.K.; Mishra, A.K. Status of brick kilns stack emission in Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. J. Adv. Res. Civil. Envi. Engr. 2019, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.; Mahapatra, P.S.; Adhikari, S.; Shrestha, S.; Sharma, P.; Shrestha, K.L.; Pradhan, B.B.; Puppala, S.P. A comparative study of stack emissions from straight-line and zigzag brick kilns in Nepal. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajarathnam, U.; Athalye, V.; Ragavan, S.; Maithel, S.; Lalchandani, D.; Kumar, S.; Baum, E.; Weyant, C.; Bond, T. Assessment of air pollutant emissions from brick kilns. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 98, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) Report 2018. Pakistan Moves Toward Environmentally Friendly and Cost-Effective Brick Kilns. Available online: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/news/pakistan-moves-toward-environmentally-friendly-and-cost-effective-brick-kilns (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Haque, M.I.; Nahar, K.; Kabir, M.H.; Salam, A. Particulate black carbon and gaseous emission from brick kilns in Greater Dhaka region, Bangladesh. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2018, 11, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttikunda, S.K.; Begum, B.A.; Wadud, Z. Particulate pollution from brick kiln clusters in the Greater Dhaka region, Bangladesh. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2013, 6, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyant, C.; Athalye, V.; Ragavan, S.; Rajarathnam, U.; Lalchandani, D.; Maithel, S.; Baum, E.; Bond, T.C. Emissions from South Asian Brick Production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6477–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulinawati, H.; Khairani, T.; Siami, L. Analysis of indoor and outdoor particulate (PM2.5) at a women and children’s hospital in West Jakarta. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 737, 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sametoding, G.R. Spatial Modeling of Particulate Matter (PM2.5, PM10 and PM1) Using Thiessen Polygon Method to Estimate the Exposed Population in Jakarta. Undergraduate Thesis, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung, Indonesia, 2021. (Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Nadzir, M.S.M.; Ooi, M.C.G.; Alhasa, K.M.; Bakar, M.A.A.; Mohtar, A.A.A.; Othman, M.; Nor, M.Z.M. The impact of Movement Control Order (MCO) during pandemic COVID-19 on local air quality in an urban area of Klang Valley, Malaysia. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaan, J.B.; Ballori, J.P.; Tamondong, A.M.; Ramos, R.V.; Ostrea, P.M. Estimation of PM2.5 vertical distribution using customized UAV and mobile sensors in Brgy. UP Campus, Diliman, Quezon City. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, XLII-4/W9, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.C.; Dominguez, J.G.A.; Leong, C.J.M.; Tan, C.M.S.; Materum, L. Fixed and Mobile PM2.5, CO, and CO2 measurement campaigns in light, dense, and heavy metropolitan vehicular traffic with a low-cost portable air pollution sensing device. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Eng. Res. 2019, 7, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.A.A.; Griño, M.T.T.; Tungol, T.M.V.; Bautista, J. Development of a low-cost air quality data acquisition IoT-based system using Arduino Leonardo. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2019, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunitiphisan, S.; Sirima, P.; Suree, P.; Garavig, T.; Thawat, N. Particulate matter monitoring using inexpensive sensors and internet GIS: A case study in Nan, Thailand. Eng. J. 2019, 22, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, N.K.; Long, N.Q.; Tin, N.V.; Le, D.T.T. Development of a PM2.5 forecasting system integrating low-cost sensors for Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 1454–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, C.D.T.; To, H.T. Evaluating the applicability of a low-cost sensor for measuring PM2.5 concentration in Ho Chi Minh city, Viet Nam. Sci. Technol. Dev. J. 2019, 22, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amil, N.; Latif, M.T.; Khan, M.F.; Mohamad, M. Seasonal variability of PM2.5 composition and sources in the Klang Valley urban-industrial environment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 5357–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Win, S.; Oo, M. City Research Project (Project Year 4): Citizen’s Science and Airbeam Myanmar. Project Urban Climate Resilience in Southeast Asia Partnership (UCRSEA), the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), International Partnerships for Sustainable Societies Grant (IPaSS). 2021. Available online: http://www.tei.or.th/thaicityclimate/public/research-14.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Caya, M.V.C.; Ballado, A.H., Jr.; Asis, J.K.C.; Halili, B.C.B.; Geronimo, K.M.R. Air quality monitoring platform with the integration of dual sensor redundancy mechanism through internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 10th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), Baguio City, Philippines, 29 November–2 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.J.; Ali, M.Z.; He, Y.C. Spatial calibration and PM2.5 mapping of low-cost air quality sensors. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.D.; Cui, K.P.; Yu, T.Y.; Chao, H.R.; Hsu, Y.C.; Lu, I.C.; Arcega, R.D.; Tsai, M.H.; Lin, S.L.; Chao, W.C.; et al. A big data analysis of PM2.5 and PM10 from low cost air quality sensors near traffic areas. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 1721–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, T.Y.; Chao, H.R.; Tsai, M.H.; Lin, C.C.; Lu, I.C.; Chang, W.H.; Chen, C.C.; Wang, L.J.; Lin, E.T.; Chang, C.T.; et al. Big Data Analysis for Effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Ambient PM2.5 in Areas that Were Not Locked Down. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 21002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwatcharapaiboon, J. Review Article: Toward future particulate matter situations in Thailand from supporting policy, network and economy. Future Cities Environ. 2020, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, T.N.T.; Ha, D.V.; Do, T.N.N.; Nguyen, V.H.; Ngo, X.T.; Phan, V.H.; Nguyen, N.D.; Bui, Q.H. Air pollution monitoring network using low-cost sensors, a case study in Hanoi, Vietnam. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 266, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarathna, M.; Jayaratne, R.; Morawska, L.; Guo, Y.; Knibbs, L.D.; Bui, D.; Abeysundara, S.; Weerasooriya, R.; Bowatte, G. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on air quality of Sri Lankan cities. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. Remediat. 2021, 9, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Ho, Y.H.; Wu, H.C.; Liu, H.M.; Hsieh, H.H.; Huang, Y.T.; Lung, S.C.C. An Open framework for participatory PM2.5 monitoring in smart cities. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 14441–14454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapour, A.; Tzeng, W.G. RL-PMAgg: Robust aggregation for PM2.5 using deep RL-based trust management system. Internet Things 2021, 13, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Wang, Y.B.; Yu, H.L. An efficient spatiotemporal data calibration approach for the low-cost PM2.5 sensing network: A case study in Taiwan. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ho, Y.; Hsieh, H.; Huang, S.; Lee, H.; Mahajan, S. ADF: An anomaly detection framework for large-scale PM2.5 sensing systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozler, S.; Johnson, K.K.; Bergin, M.H.; Schauer, J.J. Personal exposure to PM2.5 in the various microenvironments as a traveler in southeast Asian countries. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 14, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shupler, M.; Hystad, P.; Birch, A.; Miller-Lionberg, D.; Jeronimo, M.; Kazmi, K.; Yusuf, S.; Brauer, M. Household and personal air pollution exposure measurements from 120 communities in eight countries: Results from the PURE-AIR study. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e451–e462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.T.M.; Ngoh, J.R.; Balasubramanian, R. Assessment of the integrated personal exposure to particulate emissions in urban micro-environments: A Pilot Study. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win-Shwe, T.T.; Thein, Z.L.; Aung, W.Y.; Yi, E.E.P.N.; Maung, C.; Nway, N.C.; Thant, Z.; Suzuki, T.; Mar, O.; Ishigaki, Y.; et al. Improvement of GPS-attached pocket PM2.5 measuring device for personal exposure assessment. J. UOEH 2020, 42, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Yum, Y.; George, K.; Kwon, J.W.; Kim, W.K.; Baek, H.S.; Suh, D.I.; Yang, H.J.; Yoo, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. Real-time low-cost personal monitoring for exposure to PM2.5 among asthmatic children: Opportunities and challenges. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, S. Exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and noise at bus stops in Chennai, India. J. Transp. Health 2021, 22, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L.; Rutter, G.; Iverson, L.; Wilson, L.; Chadha, T.S.; Wilkinson, P.; Milojevic, A. Personal exposure monitoring of PM2.5 among US diplomats in Kathmandu during the COVID-19 lockdown, March to June 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 144836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Oanh, N.T.; Ekbordin, W.; Ha Chi, N.N.; Kraichat, T.; Tiprada, M. Emissions from street cooking activities in Bangkok and effects on PM2.5 exposure. In Proceedings of the “Tackle Air Quality and Human Health with New Thinking and Technology” Session, Sustainability Research and Innovation Congress 2021, Brisbane, Australia, and online. 12–15 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.C.V.; Lung, S.C.C.; Liu, C.H.; Wen, T.Y.J.; Hu, S.C.; Chen, L.J. Evaluation and application of a novel low-cost wearable sensing device in assessing real-time PM2.5 exposure in Major Asian Transportation Modes. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Hama, S.; Nogueira, T.; Abbass, R.A.; Brand, V.S.; Andrade, M.D.F.; Asfaw, A.; Aziz, K.H.; Cao, S.J.; El-Gendy, A.; et al. In-car particulate matter exposure across ten global cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambaliza, M.O.L.; Cruz, M.T.; Delos Reyes, I.; Leung, G.F.; Gotangco, C.K.Z.; Lung, S.C.C.; Abalos, G.F.; Chan, C.L.; Collado, J.T. Characterization of the spatial and temporal distribution of fine particulate pollution in a Monsoon Asia Megacity: An assessment of personal exposure of a high risk occupational group in Metro Manila, Philippines. In Proceedings of the “Tackle Air Quality and Human Health with New Thinking and Technology” Session, Sustainability Research and Innovation Congress 2021, Brisbane, Australia, and online. 12–15 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hlaing, O.M.M.T.; Lwin, N.N.; Tun, Y.N.; Soe, M.A.M.; Lung, S.C.C.; Oanh, N.T.K. Health risk assessment of PM2.5 exposure on waste handling workers in Mandalay, Myanmar: Raising awareness of the decision makers. In Proceedings of the “Tackle Air Quality and Human Health with New Thinking and Technology” Session, Sustainability Research and Innovation Congress 2021, Brisbane, Australia, and online. 12–15 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, R.D.; Brook, J.R.; Urch, B.; Vincent, R.; Rajagopalan, S.; Silverman, F. Inhalation of fine particulate air pollution and ozone causes acute arterial vasoconstriction in healthy adults. Circulation 2002, 105, 1534–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate Matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gauderman, W.J.; Vora, H.; McConnell, R.; Berhane, K.; Gilliland, F.; Thomas, D.; Lurmann, F.; Avol, E.; Kunzli, N.; Jerrett, M.; et al. Effect of exposure to traffic on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age: A cohort study. Lancet 2007, 369, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prado Bert, P.; Mercader, E.M.H.; Pujol, J.; Sunyer, J.; Mortamais, M. The effects of air pollution on the brain: A Review of studies interfacing environmental epidemiology and neuroimaging. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coker, E.S.; Martin, J.; Bradley, L.D.; Sem, K.; Clarke, K.; Sabo-Attwood, T. A time series analysis of the ecologic relationship between acute and intermediate PM2.5 exposure duration on neonatal intensive care unit admissions in Florida. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiger, R.E.; Miller, J.P.; Bigger, J.T.; Moss, A.J. Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1987, 59, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Larson, M.G.; Venditti, F.J.; Manders, E.S.; Evans, J.C.; Feldman, C.L.; Levy, D. Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events—The Framingham heart study. Circulation 1996, 94, 2850–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A.; Eatough, D.J.; Gold, D.R.; Pang, Y.; Nielsen, K.R.; Nath, P.; Verrier, R.L.; Kanner, R.E. Acute exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and heart rate variability. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; O’Neill, M.S.; Vokonas, P.S.; Sparrow, D.; Wright, R.O.; Coull, B.; Nie, H.; Hu, H.; Schwartz, J. Air pollution and heart rate variability. Epidemiology 2008, 19, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.T.; Dong, Y.N.; Xu, M.X.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhao, J.X. Exercise and air pollutants exposure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Life Sci. 2019, 218, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrett, M.; Burnet, R.T.; Ma, R.; Pope, C.A.; Krewski, D.; Newbold, B.; Thurston, G.; Shi, Y.; Finkelstein, N.; Calle, E.E.; et al. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology. 2005, 16, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, M.C.M.; Lung, S.C.C.; Cheng, C.H. Demonstrating the Applicability of Smartwatches in PM2.5 Health Impact Assessment. Sensors 2021, 21, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Breitner, S.; Cascio, W.E.; Devlin, R.B.; Neas, L.M.; Diaz-Sanchez, D.; Kraus, W.E.; Schwartz, J.; Hauser, E.R.; Peters, A.; et al. Short-term effects of fine particulate matter and ozone on the cardiac conduction system in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weichenthal, S.; Kulka, R.; Dubeau, A.; Martin, C.; Wang, D.; Dales, R. Traffic-related air pollution and acute changes in heart rate variability and respiratory function in urban cyclists. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nazelle, A.; Fruin, S.; Westerdahl, D.; Martinez, D.; Ripoll, A.; Kubesch, N.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. A travel mode comparison of commuters’ exposures to air pollutants in Barcelona. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 59, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, W.B.; Horvath, S.M. Air Pollution and Athletic Performance; Thomas Publisher: Springfield, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Strava Releases 2020 Year in Sport Data Report Containment, Insights from Strava’s Global Community of over 73 Million Athletes Shed Light on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Competition, Performance and Habits. 2021. Available online: https://blog.strava.com/press/yis2020/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Atkinson, G. Air pollution and exercise. Sports Excercise Inj. 1987, 3, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter, A.; Pestel, N.; Sommer, E. Productivity effects of air pollution: Evidence from professional soccer. Labour Econ. 2017, 48, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, N.D.; Le, T.P.L.; Nguyen, Q.B. The impacts of traffic related air pollution on respiratory health: A comparison study between high and low exposure groups. J. Med. Res. HaNoi Med. Univ. 2020, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Waterfield, S.L., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., Zhou, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, In press; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Heo, S.; Bell, M.L.; Lee, J.T. Comparison of health risks by heat wave definition: Applicability of wet-bulb globe temperature for heat wave criteria. Environ. Res. 2019, 168, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7 (Suppl. 1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| (a) Country | Population [15] (Estimate, Thousands) | Total Area [16] (km2) | Population Density of the Entire Country (Person/km2) | GD per Capita [17] (USD) | Employment in Industry [18] (% of Total Employment) |

| Bangladesh | 163,046 | 143,998 | 1132.3 | 1856 | 21 |

| Indonesia | 270,626 | 1,904,569 | 142.1 | 4136 | 22 |

| Malaysia | 31,950 | 329,847 | 96.9 | 11,414 | 27 |

| Myanmar | 54,045 | 676,578 | 79.9 | 1477 | 17 |

| Philippines | 108,117 | 300,000 | 360.4 | 3485 | 19 |

| Taiwan | 23,774 | 36,193 | 656.9 | 25,941 [19] | 63 [20] |

| Thailand | 69,626 | 513,115 | 135.7 | 7807 | 23 |

| Vietnam | 96,462 | 331,689 | 290.8 | 2715 | 27 |

| (b) Country/Capital City | Population in the Capital City in 2019 (Estimate, Thousands) | Population Density in the Capital City in 2019 (Person/km2) | Annual Mean of Hourly PM2.5 [21] (μg/m3, Capital City, 2019) | Annual Mean of Hourly PM2.5 [10] (μg/m3, Capital City, 2020) | |

| Bangladesh/Dhaka | 20,284 [22] | 23,234 [22] | 83.3 | 77.1 | |

| Indonesia/Jakarta | 10,639 [22] | 15,900 [23] | 49.4 | 39.6 | |

| Malaysia/Kuala Lumpur | 7780 [22] | 7802 [24] | 21.6 | 16.5 | |

| Myanmar/Yangon | 5244 [22] | 12,308 [22] | 31 | NA | |

| Philippines/Metro Manila | 13,699 [22] | 21,765 [25] | 18.2 | 13.1 | |

| Taiwan/Taipei | 2645 [26] | 9473 [26] | 13.9 | 12.6 | |

| Thailand/Bangkok | 10,350 [22] | 6598 [27] | 22.8 | 20.6 | |

| Vietnam/Hanoi | 4480 [22] | 2410 [28] | 46.9 | 37.9 | |

| Country | Studied Area | Year | PM2.5 Levels (μg/m3) | Sensor Used | Calibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Dhaka [8] | 2017 | 76.0 ± 16.2 | AEROCET 531S | Yes |

| Indonesia | Jakarta [77] | 2019 | 50–65 | Edimax AirBox AI-1001W V3 | Yes |

| Jakarta [78] | 2018–2019 | 53.7 (0–175) | Alphasense OPC-N2 | Yes | |

| Malaysia | Petaling Jaya near Kuala Lumpur [79] | Nov 2019–Feb 2020 | 19.1 | AiRBOXSense | Yes |

| Myanmar | Yangon [66] | 2018 | Hlaingtharyar, Morning 164 ± 52 Evening 100 ± 35 | Pocket PM2.5 Sensor | Yes |

| Yangon [66] | 2018 | Kamayut, Morning 91 ± 37 Evening 60 ± 22 | Pocket PM2.5 Sensor | Yes | |

| Mandalay [65] | 2018–2019 | Summer 94 ± 10 μg/m3 Winter 53 ± 2 μg/m3 | AS-LUNG-O | Yes | |

| Philippines | Quezon City, Metro Manila [80] | 2017 | -- | CrowdSSense | No |

| Manila and Taguig and Makati Cities, Metro Manila [81] | 2019 | -- | -- | No | |

| Balanga City, Bataan Province [82] | -- | -- | DSM501A | No | |

| Taiwan | Central Taiwan [9] | 2017 | July 17.5 ± 8.9; December 29.2 ± 10.6 | AS-LUNG-O | Yes |

| Taipei [7] | 2018 | 18.4 ± 10.6 | AS-LUNG-O | Yes | |

| Taipei [47] | 2018–2019 | Location A 17.2 ± 9.1; Location B 10.8 ± 3.9 | AS-LUNG-O | Yes | |

| Thailand | Mae Shot, Northern Thailand [34] | Mar–Apr 2018 | 13–280 (24h) | Plantower PMS7003 | Yes |

| Nan, Northern Thailand [83] | NA | <5–37 (flight track) | Plantower PMS 3003 (on Drone) | Yes | |

| Vietnam | Hanoi and Thai Nguyen Province [33] | Oct 2017–Apr 2018 | Hourly: three sites, 57.5, 54.9, and 53.6 | Panasonic PM2.5 sensors | Yes |

| Ho Chi Minh City [84] | 2017 | Maximum: 30–34 Minimum: 5–10 | Plantower PMS 3003 | Yes | |

| Ho Chi Minh City [85] | Oct–Dec 2018 | Sensor 1: 33.86 Sensor 2: 34.16 | Plantower PMS 3003 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lung, S.-C.C.; Thi Hien, T.; Cambaliza, M.O.L.; Hlaing, O.M.T.; Oanh, N.T.K.; Latif, M.T.; Lestari, P.; Salam, A.; Lee, S.-Y.; Wang, W.-C.V.; et al. Research Priorities of Applying Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensors in Southeast Asian Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031522

Lung S-CC, Thi Hien T, Cambaliza MOL, Hlaing OMT, Oanh NTK, Latif MT, Lestari P, Salam A, Lee S-Y, Wang W-CV, et al. Research Priorities of Applying Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensors in Southeast Asian Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031522

Chicago/Turabian StyleLung, Shih-Chun Candice, To Thi Hien, Maria Obiminda L. Cambaliza, Ohnmar May Tin Hlaing, Nguyen Thi Kim Oanh, Mohd Talib Latif, Puji Lestari, Abdus Salam, Shih-Yu Lee, Wen-Cheng Vincent Wang, and et al. 2022. "Research Priorities of Applying Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensors in Southeast Asian Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031522

APA StyleLung, S.-C. C., Thi Hien, T., Cambaliza, M. O. L., Hlaing, O. M. T., Oanh, N. T. K., Latif, M. T., Lestari, P., Salam, A., Lee, S.-Y., Wang, W.-C. V., Tsou, M.-C. M., Cong-Thanh, T., Cruz, M. T., Tantrakarnapa, K., Othman, M., Roy, S., Dang, T. N., & Agustian, D. (2022). Research Priorities of Applying Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensors in Southeast Asian Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031522