Outcomes of a Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Model at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

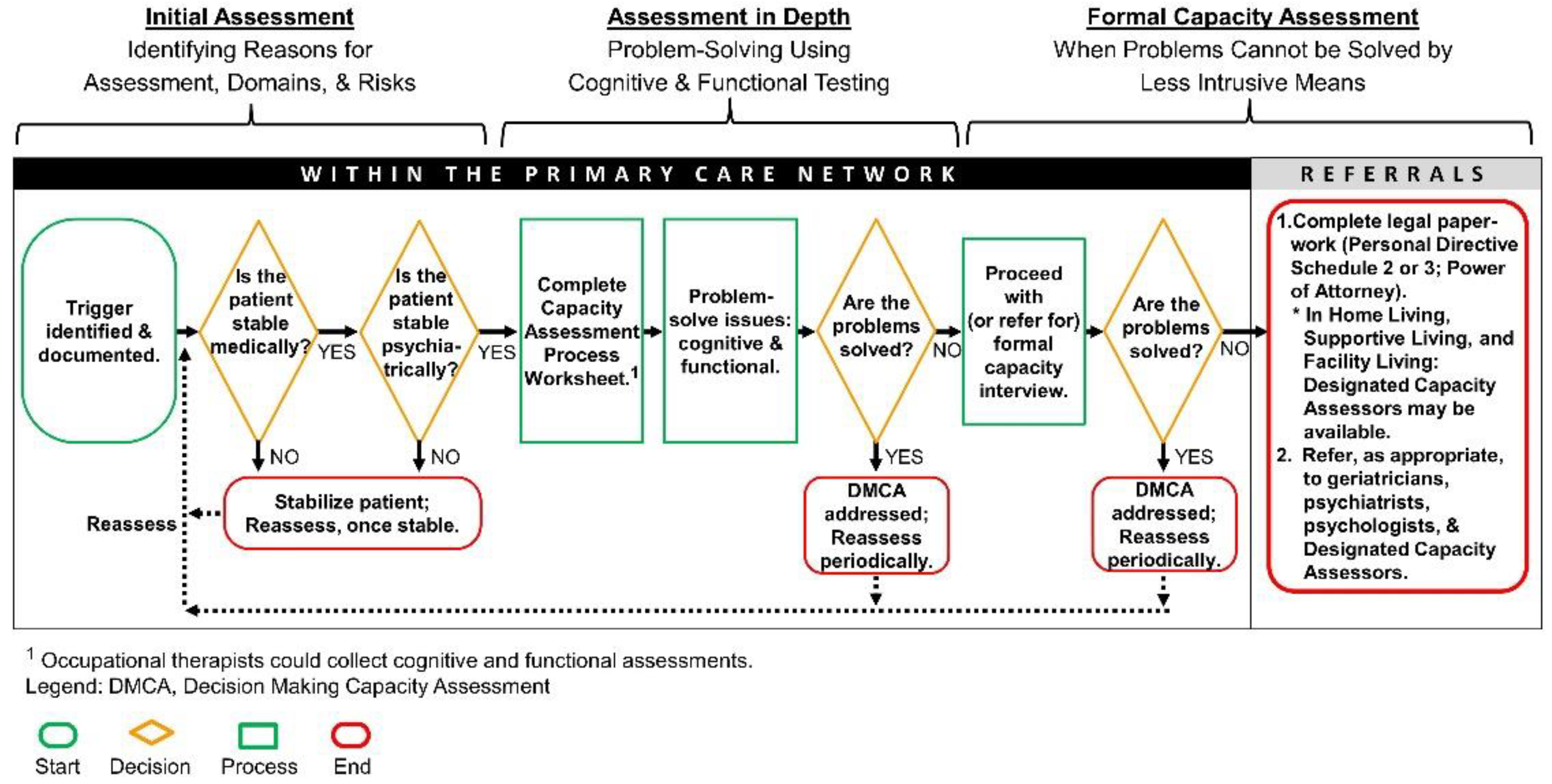

2.2. Process of DMCA

2.3. Outcome Measures and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Domains Identified in the Patients

3.2. Disciplines Involved and Referrals Made

3.3. Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barstow, C.; Shahan, B.; Roberts, M. Evaluating Medical Decision-Making Capacity in Practice. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 98, 40–46. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0701/p40.html (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Strong, J.V.; Bamonti, P.; Jacobs, M.L.; Moye, J.A. Capacity assessment training in geropsychology: Creating and evaluating an outpatient capacity clinic to fill a training gap. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2021, 42, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.B.; Simões, M.R.; Firmino, H.; Peisah, C. Financial and testamentary capacity evaluations: Procedures and assessment instruments underneath a functional approach. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, R.B.; Thielke, S. Protocol for the assessment of patient capacity to make end-of-life treatment decisions. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, J.; Thompson, R. Promoting positive approaches to dementia care in nursing. Nurs. Stand. 2010, 25, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. First WHO Ministerial Conference on Global Action against Dementia; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/179537/9789241509114_eng.%20pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- World Health Organization. The Epidemiology and Impact of Dementia: Current State and Future Trends; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_epidemiology.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Alzheimer Society of Canada. Dementia Numbers in Canada; Alzheimer Society of Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. Available online: https://www.alz.org/ca/dementia-alzheimers-canada.asp#:~:text=Over%20747%2C000%20Canadians%20are%20living,crisis%20that%20must%20be%20addressed (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Personal Directive Act; c P-6; RSA: 2000. Available online: https://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/p06.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Charles, L.; Parmar, J.; Bremault-Phillips, S.; Dobbs, B.; Sacry, L.; Sluggett, B. Physician education on decision-making capacity assessment: Current state and future directions. Can. Fam. Physician 2017, 63, e21–e30. Available online: https://www.cfp.ca/content/63/1/e21 (accessed on 23 June 2021). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parmar, J.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Charles, L. The development and implementation of a decision-making capacity assessment model. Can. Geriatr. J. 2015, 18, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, L.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Pike, A.; Vokey, C.; Kilkenny, T.; Johnson, M.; Tian, P.G.J.; Babenko, O.; Dobbs, B.; Parmar, J. Decision-making capacity assessment education. J. Am. Geratr. Soc. 2021, 69, E9–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, L.; Torti, J.M.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Dobbs, B.; Tian, P.G.J.; Khera, S.; Abbasi, M.; Chan, K.; Carr, F.; Parmar, J. Developing a decision-making capacity assessment clinical pathway for use in primary care: A qualitative exploratory case study. Can. Geriatr. J. 2021, 24, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell, H.; Lee, J.H.; Sankaran, S. Review of capacity assessments and recommendations for examining capacity. N. Z. Med. J. 2013, 126, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G.; Galbraith, S.; Woodward, J.; Holland, A.; Barclay, S. Should they have a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy? The importance of assessing decision-making capacity and the central role of a multidisciplinary team. Clin. Med. 2014, 14, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, S.; Stewart, C.; Chiarella, M. Documentation of capacity assessment and subsequent consent in patients identified with delirium. J. Bioethical Inq. 2016, 13, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.W.; Wilson, G.; Okon-Rocha, E.; Owen, G.S.; Wilson Jones, C. Capacity in vacuo: An audit of decision-making capacity assessments in a liaison psychiatry service. BJPsych Bull. 2017, 41, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Adams, D.; Campbell, C. End-of-life care in neurodegenerative conditions: Outcomes of a specialist palliative neurology service. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2013, 19, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act; c A-4.2; SA: 2008. Available online: https://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/A04P2.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Brémault-Phillips, S.C.; Parmar, J.; Friesen, S.; Rogers, L.G.; Pike, A.; Sluggett, B. An evaluation of the Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Model. Can. Geriatr. J. 2016, 19, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorinmade, O.; Strathdee, G.; Wilson, C.; Kessel, B.; Odesanya, O. Audit of fidelity of clinicians to the Mental Capacity Act in the process of capacity assessment and arriving at best interests decisions. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2011, 12, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, C.; Davey, K.; Ter Meulen, R.; Coulthard, E.; Kehoe, P.G. Tools for testing decision-making capacity in dementia. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newfoundland & Labrador Association of Social Workers. Social Work & Decision Specific Capacity Assessments; Newfoundland & Labrador Association of Social Workers: St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2012. Available online: https://nlcsw.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/Social_Work_And_Decision-Specific_Capacity_Assessments_Final.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Simel, D.L.; Sessums, L.L.; Zembrzuska, H.; Jackson, J.L. Medical Decision-Making Capacity. In The Rational Clinical Examination: Evidence-based Clinical Diagnosis; Simel, D.L., Rennie, D., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. Available online: http://jamaevidence.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=845§ionid=61357673 (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Ranjith, G.; Hotopf, M. ‘Refusing treatment--please see’: An analysis of capacity assessments carried out by a liaison psychiatry service. J. R. Soc. Med. 2004, 97, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dementia: A Public Health Priority; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_executivesummary.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- College of Family Physicians of Canada Working Group on the Assessment of Competence in Care of the Elderly. Priority Topics and Key Features for the Assessment of Competence in Care of the Elderly; College of Family Physicians of Canada: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2017. Available online: https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Resources/Education/COE_KF_Final_ENG.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Charles, L.A.; Frank, C.C.; Allen, T.; Lozanovska, T.; Arcand, M.; Feldman, S.; Lam, R.E.; Mehta, P.G.; Mangal, N.Y. Identifying the priority topics for the assessment of competence in care of the elderly. Can. Geriatr. J. 2018, 21, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brémault-Phillips, S.; Pike, A.; Charles, L.; Roduta-Roberts, M.; Mitra, A.; Friesen, S.; Moulton, L.; Parmar, J. Facilitating implementation of the Decision-Making Capacity Assessment (DMCA) Model: Senior leadership perspectives on the use of the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN) Model and frameworks. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, S.; Jones, S.; Macdonald, A. Capacity assessments on medical in-patients referred to social workers for care home placement. Psychiatr. Bull. 2008, 32, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| % (n/N) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 76 years old (SD: 10.5; Range: 49–98) |

| Sex | Females: 51.1% (45/88) Males: 48.9% (43/88) |

| Patient’s Living Arrangements | |

| Home | 97.5% (77/79) |

| Supportive Living/Long Term Care | 2.5% (2/79) |

| DMCA performed | 72.6% (61/84) |

| Diagnosis of Dementia | |

| With Dementia | 43.2% (38/88) |

| Unspecified Cognitive Impairment | 13.6% (12/88) |

| No Dementia | 42.2% (38/88) |

| Presence of Valid Trigger for DMCA | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 93.0% (80/86) |

| No | 7.0% (6/86) |

| Number of Domains Identified (all) | |

| 1 | 13.2% (9/68) |

| 2 | 29.4% (20/68) |

| 3 | 25.0% (17/68) |

| 4 | 30.9% (21/68) |

| 5 | 1.5% (1/68) |

| Domains Identified for DMCA | |

| Accommodation | 88.2% (60/68) |

| Healthcare | 83.8% (57/68) |

| Finances | 61.8% (42/68) |

| Legal Affairs | 36.8% (25/68) |

| Others (Employment, Social, Educational) | 7.4% (5/68) |

| Number of Disciplines Involved in the DMCA | |

| None | 1.7% (1/58) |

| 1 | 43.1% (25/58) |

| 2 | 24.1% (14/58) |

| 3 | 24.1% (14/58) |

| 4 | 6.9% (4/58) |

| Types of Disciplines Involved in the DMCA | |

| Social Worker | 81.0% (47/58) |

| Occupational Therapist | 53.4% (31/58) |

| Physicians | 22.4% (13/58) |

| LPN/RN/NP | 19.0% (11/58) |

| Medical Student | 10.3% (6/58) |

| Geriatrics/Psychiatry | 3.4% (2/58) |

| Physical Therapy | 1.7% (1/58) |

| Number of Referrals Made During the DMCA Process | |

| None | 3.4% (3/88) |

| 1 | 61.4% (54/88) |

| 2 | 27.3% (24/88) |

| 3 | 4.5% (4/88) |

| 4 | 3.4% (3/88) |

| Types of Referrals | |

| Geriatrics | 87.5% (77/88) |

| Social Worker | 25.0% (22/88) |

| Psychiatry | 15.9% (14/88) |

| Occupational Therapist | 9.1% (8/88) |

| Others (DCA, Ethics, Family Medicine, Neuropsychiatry) | 4.6% (4/88) |

| Capacity Assessment Process Worksheet Used | |

| Yes | 63.2% (55/87) |

| No | 36.8% (32/87) |

| Team Conference Held | |

| Yes | 28.9% (24/83) |

| No | 71.1% (59/83) |

| Capacity Interview Done | |

| Yes | 20.7% (18/87) |

| No | 79.3% (69/87) |

| Final Disposition | |

| Has Capacity | 23.5% (20/85) |

| Lacks Capacity | 48.2% (41/85) |

| Capacity Assessment Not Required | 8.2% (7/85) |

| Unknown | 20.0% (17/85) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charles, L.; Kothavade, U.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Chan, K.; Dobbs, B.; Tian, P.G.J.; Polard, S.; Parmar, J. Outcomes of a Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Model at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031560

Charles L, Kothavade U, Brémault-Phillips S, Chan K, Dobbs B, Tian PGJ, Polard S, Parmar J. Outcomes of a Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Model at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031560

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharles, Lesley, Utkarsha Kothavade, Suzette Brémault-Phillips, Karenn Chan, Bonnie Dobbs, Peter George Jaminal Tian, Sharna Polard, and Jasneet Parmar. 2022. "Outcomes of a Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Model at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031560

APA StyleCharles, L., Kothavade, U., Brémault-Phillips, S., Chan, K., Dobbs, B., Tian, P. G. J., Polard, S., & Parmar, J. (2022). Outcomes of a Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Model at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031560