Changes in the Lifestyle of the Spanish University Population during Confinement for COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Participants and Study Design

2.2. Instrument and Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

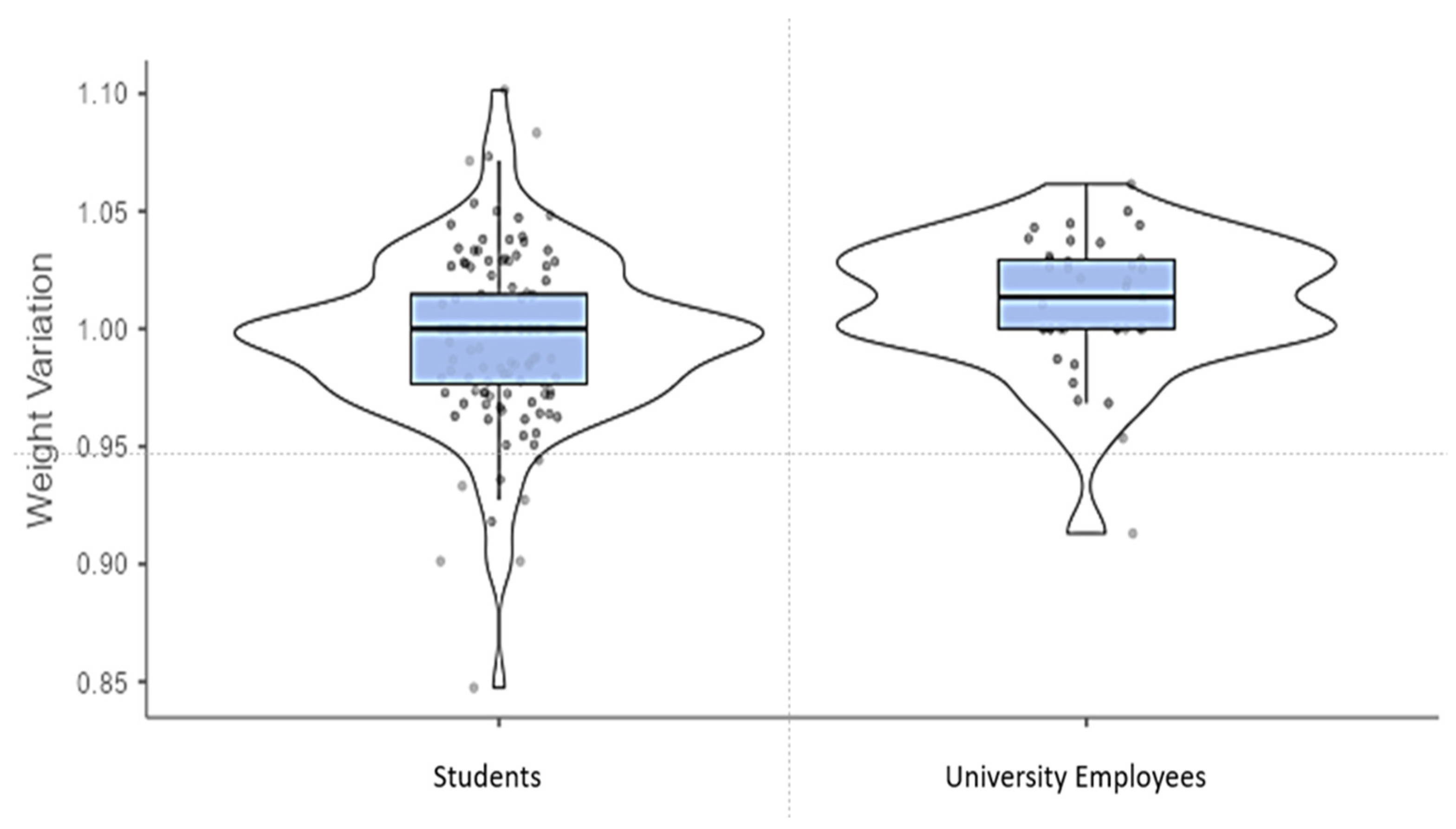

3.1. Characterization of the Sample Population

3.2. Confinement Effect on Dietary and Physical Activity Behavior

3.3. Adherence to the MD (MEDAS-14) during Confinement

3.4. Emotional Eater Behavior during Confinement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothan, H.A.; Byrareddy, S.N. The Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO EMRO. Nutrition for Adults during COVID-19. Campaigns. NCDs. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/noncommunicable-diseases/campaigns/nutrition-for-adults-during-covid-19.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de la Presidencia. Relaciones con las Cortes y Memoria Democrática. In Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de Marzo, Por El Que Se Declara El Estado de Alarma Para La Gestión de La Situación de Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada Por El COVID-19; 2020; Volume BOE-A-2020-3692, pp. 25390–25400. [Google Scholar]

- BOE.Es–BOE-A-2020-4767 Orden SND/380/2020, de 30 de Abril, Sobre Las Condiciones En Las Que Se Puede Realizar Actividad Física No Profesional al Aire Libre Durante La Situación de Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada Por El COVID-19. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2020-4767 (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Jayawardena, R.; Misra, A. Balanced Diet Is a Major Casualty in COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 1085–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, L.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Labesse, M.; Nicklaus, S. Food Choice Motives and the Nutritional Quality of Diet during the COVID-19 Lockdown in France. Appetite 2021, 157, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Allès, B.; Andreeva, V.A.; Baudry, J.; Charreire, H.; Deschamps, V.; Egnell, M.; et al. Diet and Physical Activity during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Lockdown (March–May 2020): Results from the French NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmozzino, F.; Visioli, F. Covid-19 and the Subsequent Lockdown Modified Dietary Habits of Almost Half the Population in an Italian Sample. Foods 2020, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, E.; Ramírez-Vargas, G.; Avellaneda-López, Y.; Orellana-Pecino, J.I.; García-Marín, E.; Díaz-Jimenez, J. Eating Habits and Physical Activity of the Spanish Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lewis, E.D.; Pae, M.; Meydani, S.N. Nutritional Modulation of Immune Function: Analysis of Evidence, Mechanisms, and Clinical Relevance. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidi, A.M.; Kokkinos, A.; Katechaki, E.; Ros, E.; Mantzoros, C.S. Mediterranean Diet as a Nutritional Approach for COVID-19. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2021, 114, 154407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Mediterranean Diet and Multiple Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies and Randomised Trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, A.; Nolen-Doerr, E.; Mantzoros, C.S. The Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Metabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials in Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H.; De Filippis, A.; Santarcangelo, C.; Daglia, M. Epigenetic Regulation by Polyphenols in Diabetes and Related Complications. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 13, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, L.; Perez-Lopez, P.; Giampieri, F.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y.; Quiles, J.L.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. The Genetic Aspects of Berries: From Field to Health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.L.; Rivas-García, L.; Varela-López, A.; Llopis, J.; Battino, M.; Sánchez-González, C. Do Nutrients and Other Bioactive Molecules from Foods Have Anything to Say in the Treatment against COVID-19? Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabetakis, I.; Lordan, R.; Norton, C.; Tsoupras, A. COVID-19: The Inflammation Link and the Role of Nutrition in Potential Mitigation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Cordero, M.D.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y.; Afrin, S.; Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Astolfi, P.; Rubini, C.; et al. Strawberry Consumption Improves Aging-Associated Impairments, Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Functionality through the AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Cascade. Food Chem. 2017, 234, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavite, P.; Donzelli, A. Hesperidin and SARS-CoV-2: New Light on the Healthy Function of Citrus Fruits. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh Ismail, L.; Osaili, T.M.; Mohamad, M.N.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Jarrar, A.H.; Abu Jamous, D.O.; Magriplis, E.; Ali, H.I.; Al Sabbah, H.; Hasan, H.; et al. Eating Habits and Lifestyle during COVID-19 Lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusseini, N.; Alqahtani, A. COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Eating Habits in Saudi Arabia. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, N.; Sadowski, A.; Laila, A.; Hruska, V.; Nixon, M.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J.; on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odone, A.; Lugo, A.; Amerio, A.; Borroni, E.; Bosetti, C.; Carreras, G.; d’Oro, L.; Colombo, P.; Fanucchi, T.; Ghislandi, S.; et al. COVID-19 Lockdown Impact on Lifestyle Habits of Italian Adults. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, M.; Mennitti, C.; Gentile, A.; Correale, L.; Buzzachera, C.F.; Ferraris, C.; Montomoli, C.; Frisso, G.; Borrelli, P.; Scudiero, O. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Job Activity, Dietary Behaviours and Physical Activity Habits of University Population of Naples, Federico II-Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating Habits and Lifestyle Changes during COVID-19 Lockdown: An Italian Survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinisterra Loaiza, L.I.; Vázquez Belda, B.; Miranda López, J.M.; Cepeda, A.; Cardelle Cobas, A. Food habits in the Galician population during confinement byCOVID-19. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeymans, J.; Luijckx, E.; Rogan, S.; Haas, K.; Baur, H. Physical Activity, Nutritional Habits, and Sleeping Behavior in Students and Employees of a Swiss University During the COVID-19 Lockdown Period: Questionnaire Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e26330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celorio-Sardà, R.; Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Zerón-Rugerio, M.F.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Illán-Villanueva, M.; Farran-Codina, A.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M.; Del Carmen Vidal-Carou, M. Effect of COVID-19 Lockdown on Dietary Habits and Lifestyle of Food Science Students and Professionals from Spain. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Prado-Laguna, M.d.C.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle in University Students: Changes during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetto, C.; Aiello, M.; Gentili, C.; Ionta, S.; Osimo, S.A. Increased Emotional Eating during COVID-19 Associated with Lockdown, Psychological and Social Distress. Appetite 2021, 160, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de Diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y Garantía de los Derechos Digitales. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2018/BOE-A-2018-16673-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data (United Kingdom General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2016/679/article/94# (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Sociedad Española De Nutrición Comunitaria. Available online: https://www.nutricioncomunitaria.org/es/noticia/se-presentan-las-nuevas-guias-alimentarias-para-la-poblacion-espanola-elaboradas-por-la-senc-con-la- (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Older Spanish Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garaulet, M. Validación de un cuestionario de comedores emocionales, para usar en casos de obesidad; cuestionario de comedor emocional (CCE). Nutr. Hosp. 2012, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallah, S.I.; Ghorab, O.K.; Al-Salmi, S.; Abdellatif, O.S.; Tharmaratnam, T.; Iskandar, M.A.; Sefen, J.A.N.; Sidhu, P.; Atallah, B.; El-Lababidi, R.; et al. COVID-19: Breaking down a Global Health Crisis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Cinelli, G.; Bigioni, G.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Bianco, F.F.; Caparello, G.; Camodeca, V.; Carrano, E.; et al. Psychological Aspects and Eating Habits during COVID-19 Home Confinement: Results of EHLC-COVID-19 Italian Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Aranda, F.; Munguía, L.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Etxandi, M.; Baenas, I.; Granero, R.; Sánchez, I.; Ortega, E.; Andreu, A.; et al. COVID Isolation Eating Scale (CIES): Analysis of the Impact of Confinement in Eating Disorders and Obesity—A Collaborative International Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Vives, F.; Dueñas, J.-M.; Vigil-Colet, A.; Camarero-Figuerola, M. Psychological Variables Related to Adaptation to the COVID-19 Lockdown in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 565634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, D.; Bansal, S.; Goyal, S.; Garg, A.; Sethi, N.; Pothiyill, D.I.; Sreelakshmi, E.S.; Sayyad, M.G.; Sethi, R. Psychological Impact of Mass Quarantine on Population during Pandemics-The COVID-19 Lock-Down (COLD) Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzman, J. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health. Psychiatr. Pol. 2020, 54, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reyes-Olavarría, D.; Latorre-Román, P.Á.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.P.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Delgado-Floody, P. Positive and Negative Changes in Food Habits, Physical Activity Patterns, and Weight Status during COVID-19 Confinement: Associated Factors in the Chilean Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, M.P.; Gillebaart, M.; Schlinkert, C.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Derksen, E.; Mensink, F.; Hermans, R.C.J.; Aardening, P.; de Ridder, D.; de Vet, E. Eating Behavior and Food Purchases during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Study among Adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2021, 157, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Ruíz-López, M.D. Changes in Dietary Behaviours during the COVID-19 Outbreak Confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Araluce, R.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Fernández-Lázaro, C.I.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Gea, A.; Carlos, S. Mediterranean Diet and the Risk of COVID-19 in the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” Cohort. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditano-Vázquez, P.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Galeano-Valle, F.; Pérez-Caballero, A.I.; Demelo-Rodríguez, P.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Katsiki, N.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Alvarez-Sala-Walther, L.A. The Fluid Aspect of the Mediterranean Diet in the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: The Role of Polyphenol Content in Moderate Consumption of Wine and Olive Oil. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Galiot, A.; Goñi, I. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Pattern, Cognitive Status and Depressive Symptoms in an Elderly Non-Institutionalized Population. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Muñoz, L.M.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Graciani, A.; López-García, E.; Mesas, A.E.; Aguilera, M.T.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Pattern Has Declined in Spanish Adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lima, C.K.T.; de M. Medeiros Carvalho, P.M.; Lima, I.d.A.A.S.; Nunes, J.V.A.d.O.; Saraiva, J.S.; de Souza, R.I.; da Silva, C.G.L.; Neto, M.L.R. The Emotional Impact of Coronavirus 2019-NCoV (New Coronavirus Disease). Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Mood, Food, and Obesity. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yannakoulia, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Tsetsekou, E.; Fappa, E.; Papageorgiou, C.; Stefanadis, C. Eating Habits in Relations to Anxiety Symptoms among Apparently Healthy Adults: A Pattern Analysis from the ATTICA Study. Appetite 2008, 51, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, M.; López, M.T.I.; Miguel, M.; Garcés-Rimón, M. Physical and Psychological Effects Related to Food Habits and Lifestyle Changes Derived from Covid-19 Home Confinement in the Spanish Population. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.M.; Kamel, M.M. Dietary Habits in Adults during Quarantine in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic. Obes. Med. 2020, 19, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total N = 168 (100%; CI) | Students N = 129 (76.8%; CI) | UE N = 39 (23.2%; CI) | p-Value 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 112 (66.7%; 58.9–73.7) | 92 (71.3%; 62.6–78.9) | 20 (51.3%; 34.7–67.5) | <0.05 | |

| Men | 56 (33.3%; 26.2–41.0) | 37 (28.7%; 21.0–37.3) | 19 (48.7%; 32.4–65.2) | ||

| Birthplace | |||||

| Spain | 133 (79.2%; 72.2–85.0) | 99 (76.7%; 68.4–83.7) | 34 (87.2%; 72.5–95.7) | <0.05 | |

| Latin America | 28 (16.7%; 11.3–23.1) | 26 (20.2%; 13.6–28.1) | 2 (5.1%; 0.6–17.3) | ||

| Europe | 4 (2.4%; 0.6–5.9) | 1 (0.8%; 0.0–4.2) | 3 (7.7%; 1.6–20.8) | ||

| Others | 3 (1.8%; 0.3–5.1) | 3 (2.3%; 0.4–6.6) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Place of Residence | |||||

| Family home | 128 (76.2%; 69.0–82.4) | 97 (75.2%; 66.8–82.3) | 31 (79.5%; 63.5–90.7) | 0.081 | |

| Shared flat | 19 (11.3%; 6.9–17.0) | 16 (12.4%; 7.2–19.3) | 3 (7.7%; 1.6–20.8) | ||

| Student residence | 10 (6%; 2.8–10.6) | 10 (7.8%; 3.7–13.7) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Alone | 11 (6.5%; 3.3–11.4) | 6 (4.7%; 1.7–9.8) | 5 (12.8%; 4.2–27.4) | ||

| Age Range | |||||

| <20 years | 54 (32.1%; 25.1–39.7) | 54 (41.9%; 33.2–50.8) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 | |

| 21–35 years | 80 (47.6%; 39.8–55.4) | 73 (56.6%; 47.5–65.2) | 7 (17.9%; 7.5–33.5) | ||

| >36 years | 34 (20.2%; 14.4–27.1) | 2 (1.6%; 0.1–5.4) | 32 (82.1%; 66.4–92.4) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) 3 | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 12 (7.1%; 3.7–12.1) | 12 (9.3%; 4.9–15.6) | 0 (0%) | <0.05 | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 111 (66.1%; 58.3–73.1) | 90 (69.8%; 61.0–77.5) | 21 (53.8%; 37.1–69.9) | ||

| Pre-obesity (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 36 (21.4%; 15.4–28.4) | 22 (17.1%; 11.0–24.6) | 14 (35.9%; 21.2–52.8) | ||

| Obesity class I and II (30–34.9 kg/m2) | 9 (5.4%; 2.4–9.9) | 5 (3.9%; 1.2–8.8) | 4 (10.3%; 2.8–24.2) |

| Total N = 168 (100%; CI) | Students N = 129 (76.8%; CI) | UE 1 N = 39 (23.2%; CI) | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During confinement, the consumption of vegetables? | ||||

| Has increased | 69 (41.1%; 33.5–48.9) | 59 (45.7%; 36.9–54.7) | 10 (25.6%; 13.0–42.1) | 0.062 |

| Has decreased | 14 (8.3%; 4.6–13.5) | 11 (8.5%; 4.3–14.7) | 3 (7.7%; 1.6–20.8) | |

| Has stayed the same | 85 (50.6%; 42.7–58.3) | 59 (45.7%; 36.9–54.7) | 26 (66.7%; 49.7–80.9) | |

| During confinement, the consumption of dairy products? | ||||

| Has increased | 43 (25.6%; 19.1–32.8) | 35 (27.1%; 19.6–35.6) | 8 (20.5%; 9.2–36.4) | <0.05 |

| Has decreased | 21 (12.5%; 7.9–18.4) | 20 (15.5%; 9.7–22.9) | 1 (2.6%; 0.0–13.4) | |

| Has stayed the same | 104 (61.9%; 54.1–69.2) | 74 (57.4%; 48.3–66.0) | 30 (76.9%; 60.6–88.8) | |

| During confinement, the consumption of pastries and snacks? | ||||

| Has increased | 36 (21.4%; 15.4–28.4) | 31 (24%; 16.9–32.3) | 5 (12.8%; 4.2–27.4) | <0.01 |

| Has decreased | 51 (30.4%; 23.5–37.9) | 45 (34.9%; 26.7–43.7) | 6 (15.4%; 5.8–30.5) | |

| Has stayed the same | 81 (48.2%; 40.4–56.0) | 53 (41.1%; 32.5–50.0) | 28 (71.8%; 55.1–84.9) | |

| During confinement, the consumption of low alcohol drinks (wine and beer)? | ||||

| Has increased | 18 (10.7%; 6.4–16.4) | 9 (7%; 3.2–12.8) | 9 (23%; 11.1–39.3) | <0.001 |

| Has decreased | 101 (60.1%; 52.2–67.5) | 87 (67.4%; 58.6–75.4) | 14 (35.9%; 21.2–52.8) | |

| Has stayed the same | 49 (29.2%; 22.4–36.6) | 33 (25.6%; 18.3–34.0) | 16 (41%; 25.5–57.9) | |

| During confinement, your physical activity? | ||||

| Has increased | 61 (36.3%; 29.0–44.0) | 52 (40.3%; 31.7–49.3) | 9 (23.1%; 11.1–39.3) | <0.05 |

| Has decreased | 83 (49.4%; 41.6–57.2) | 57 (44.2%; 35.4–53.1) | 26 (66.7%; 49.7–80.9) | |

| Has stayed the same | 24 (14.3%; 9.3–20.5) | 20 (15.5%; 9.7–22.9) | 4 (10.3%; 2.8–24.2) |

| Total N = 168 (100%; CI) | Women N = 112 (66.6%; CI) | Men N = 56 (33.3%; CI) | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many times do you do the grocery shopping per week? | ||||

| 1 time or less per week | 129 (76.8%; 69.6–82.9) | 92 (82.1%; 73.7–88.7) | 37 (66.1%; 52.1–78.1) | <0.05 |

| 2 times or more per week | 39 (23.2%; 17.0–30.3) | 20 (17.9%; 11.2–26.2) | 19 (33.9%; 21.8–47.8) | |

| During confinement, the consumption of fish/seafood? | ||||

| Has increased | 39 (23.2%; 17.0–30.3) | 32 (28.6%; 20.4–37.8) | 7 (12.7%; 5.1–24.0) | <0.05 |

| Has decreased | 32 (19%; 13.4–25.8) | 18 (16.1%; 9.8–24.2) | 14 (25%; 14.3–38.3) | |

| Has stayed the same | 97 (57.7%; 49.8–65.3) | 62 (55.4%; 45.6–64.7) | 35 (62.5%; 48.5–75.0) | |

| Have you increased the number of meals these days? | ||||

| Has increased | 62 (36.9%; 29.6–44.6) | 48 (42.9%; 33.5–52.5) | 14 (25%; 14.3–38.3) | 0.077 |

| Has decreased | 84 (50%; 42.2–57.7) | 51 (45.5%; 36.0–55.2) | 33 (58.9%; 44.9–71.9) | |

| Has stayed the same | 22 (13.1%; 8.3–19.1) | 13 (11.6%; 6.3–19.0) | 9 (16.1%; 7.6–28.3) |

| Total N = 168 (100%; CI) | Low N = 35 (20.8%; CI) | Medium/High N = 133 (79.2%; CI) | p-Value 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 112 (66.7%; 58.9–73.7) | 25 (22.3%; 14.9–31.1) | 87 (77.6%; 68.8–85.0) | 0.502 | |

| Men | 56 (33.3%; 26.2–41.0%) | 10 (17.8%; 8.9–30.3) | 46 (82.1%; 69.6–91.0) | ||

| Birthplace | |||||

| Spain | 133 (79.2%; 72.2–85.0) | 21 (15.7%; 10.0–23.1) | 112 (84.2%; 76.8–89.9) | <0.05 | |

| Other Countries | 35 (20.8%; 14.9–27.7) | 14 (40%; 23.8–57.8) | 21 (60%; 42.1–76.1) | ||

| Students and university staff | |||||

| Students | 129 (76.8%; 69.6–82.9) | 26 (20.1%; 13.6–28.1) | 103 (79.8%; 71.8–86.3) | 0.694 | |

| UE 2 | 39 (23.2%; 17.0–30.3) | 9 (23.0%; 11.1–39.3) | 30 (76.9%; 60.6–88.8) | ||

| Place of Residence | |||||

| Family home | 128 (76.2%; 69.0–82.4) | 22 (17.1%; 11.0–24.8) | 106 (82.8%; 75.1–88.9) | <0.05 | |

| Non-family home (shared flat and student residence) | 40 (23.8%; 17.5–30.9) | 13 (32.5%; 18.5–49.1) | 27 (67.5%; 50.8–81.4) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) 3 | |||||

| Under/Normalweight (<18.5–24.9 g/m2) | 123 (73.2%; 65.8–79.7) | 23 (18.6%; 12.2–26.7) | 100 (81.3%; 73.2–87.7) | 0.260 | |

| Pre-obesity/Obesity (25–39.9 kg/m2) | 45 (26.8%;20.2–34.1) | 12 (26.6%; 14.6–41.9) | 33 (73.3%; 58.0–85.3) |

| Total N = 129 (100%; CI) | Low N = 26 (20.2%; CI) | Medium/High N = 103 (79.8%; CI) | p-Value 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | |||||

| Human Nutrition | 25 (19.4%; 12.9–27.2) | 1 (4.0%; 0.1–20.3) | 24 (96%; 79.6–99.8) | <0.05 | |

| Other degrees | 104 (80.6%; 72.7–87.0) | 25 (24.0%; 16.2–33.4) | 79 (75.9%; 66.5–83.8) | ||

| Faculty | |||||

| Health Sciences | 85 (65.9%; 57.0–74.0) | 17 (20%; 12.1–30.0) | 68 (80%; 69.9–87.8) | 0.951 | |

| Other faculties | 44 (34.1%; 25.9–42.9) | 9 (20.4%; 9.8–35.3) | 35 (79.5%; 64.6–90.1) |

| Total N = 168 (100%; CI) | Non-Emotional/ Low Emotional Eater N = 122 (72.6%; CI) | Emotional/ Very Emotional Eater N = 46 (27.4%; CI) | p-Value 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 112 (66.7%; 58.9–73.7) | 72 (64.2%; 54.6–73.1) | 40 (35.7%; 26.8–45.3) | <0.01 | |

| Men | 56 (33.3%; 26.2–41.0%) | 50 (89.2%; 78.1–95.9) | 6 (10.7%; 4.0–21.8) | ||

| Birthplace | |||||

| Spain | 133 (79.2%; 72.2–85.0) | 101 (75.9%; 67.7–82.9) | 32 (24.0%; 17.0–32.2) | 0.060 | |

| Other Countries | 35 (20.8%; 14.9–27.7) | 21 (60%; 42.1–76.1) | 14 (40%; 23.8–57.8) | ||

| Students and university staff | |||||

| Students | 129 (76.8%; 69.6–82.9) | 91 (70.5%; 61.8–78.2) | 38 (29.4%; 21.7–38.1) | 0.272 | |

| UE 3 | 39 (23.2%; 17.0–30.3) | 31 (79.4%; 63.5–90.7) | 8 (20.5%; 9.2–36.4) | ||

| Place of Residence | |||||

| Family home | 128 (76.2%; 69.0–82.4) | 95 (74.2%; 65.7–81.5) | 33 (25.7%; 18.4–34.2) | 0.406 | |

| Non-family home (shared flat and student residence) | 40 (23.8%; 17.5–30.9) | 27 (67.5%; 50.8–81.4) | 13 (32.5%; 18.5–49.1) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) 4 | |||||

| Under/Normalweight (<18.5–24.9 g/m2) | 123 (73.2%; 65.8–79.7) | 94 (76.4%; 67.9–83.6) | 29 (23.5%; 16.3–32.0) | 0.068 | |

| Pre-obesity/Obesity (25–39.9 kg/m2) | 45 (26.8%;20.2–34.1) | 28 (62.2%; 46.5–76.2) | 17 (37.7%; 23.7–53.4) |

| Total N = 129 (100%; CI) | Non-Emotional/ Low Emotional Eater N = 91 (70.5%; CI) | Emotional/ Very Emotional Eater N = 38 (29.5%; CI) | p-Value 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | |||||

| Human Nutrition | 25 (19.4%; 12.9–27.2) | 19 (76%; 54.8–906) | 6 (24%; 9.3–45.1) | 0.505 | |

| Others | 104 (80.6%; 72.7–87.0) | 72 (69.2%; 59.4–77.9) | 32 (30.7%; 22.0–40.5) | ||

| Faculty | |||||

| Health Sciences | 84 (65.6%; 56.2–73.2) | 63 (75%; 64.3–83.8) | 22 (26.1%; 17.1–36.9) | 0.216 | |

| Others | 44 (34.4%; 25.9–42.9) | 28 (63.6%; 47.7–77.5) | 16 (36.3%; 22.4–52.2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sumalla-Cano, S.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Aparicio-Obregón, S.; Crespo, J.; Eléxpuru-Zabaleta, M.; Gracia-Villar, M.; Giampieri, F.; Elío, I. Changes in the Lifestyle of the Spanish University Population during Confinement for COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042210

Sumalla-Cano S, Forbes-Hernández T, Aparicio-Obregón S, Crespo J, Eléxpuru-Zabaleta M, Gracia-Villar M, Giampieri F, Elío I. Changes in the Lifestyle of the Spanish University Population during Confinement for COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042210

Chicago/Turabian StyleSumalla-Cano, Sandra, Tamara Forbes-Hernández, Silvia Aparicio-Obregón, Jorge Crespo, María Eléxpuru-Zabaleta, Mónica Gracia-Villar, Francesca Giampieri, and Iñaki Elío. 2022. "Changes in the Lifestyle of the Spanish University Population during Confinement for COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042210