“Well, I Signed Up to Be a Soldier; I Have Been Trained and Equipped Well”: Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during COVID-19 Organizational Changes in Singapore, from the First Wave to the Path towards Endemicity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

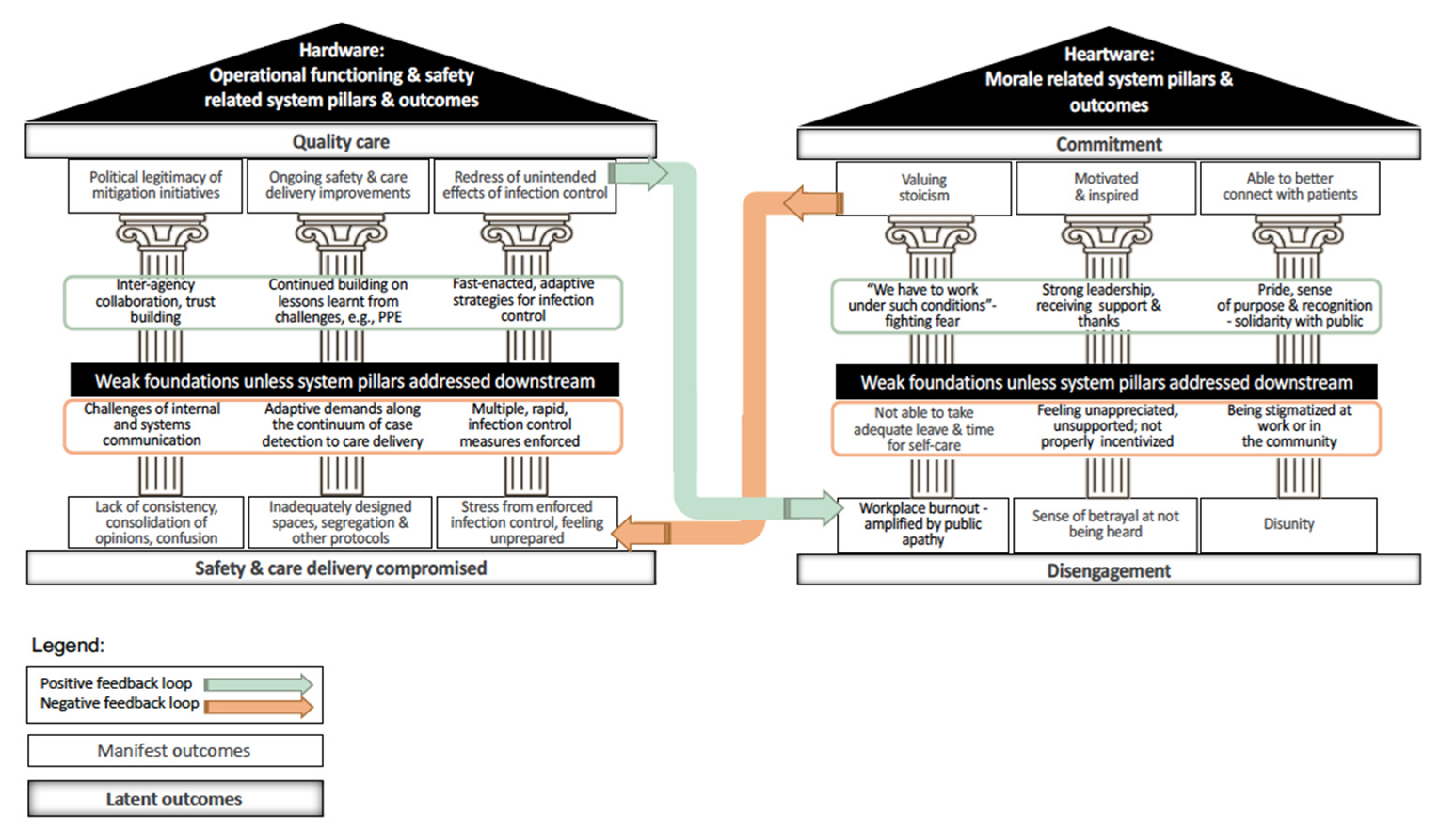

1.2. Morale and Commitment of Healthcare Workers

1.3. Operational Safety and Functioning

1.4. Problem Formulation

2. Research Questions

- How was morale experienced by HCWs in terms of breaking as well as boosting engagement and commitment?

- What barriers and enablers were experienced that affected operational safety and functioning?

3. Methods

3.1. Qualitative Approach and Research Paradigm

3.2. Researcher Team Composition and Reflexivity

3.3. Context

3.4. Sampling Strategy

3.5. Ethical Issues

3.6. Data Collection Methods

3.7. Data Collection Instruments and Technologies

3.8. Units of Study

3.9. Data Processing

3.10. Data Analysis

3.11. Techniques to Enhance Trustworthiness

4. Results

4.1. How Was Morale Experienced by Healthcare Workers in Terms of Breaking as well as Boosting Engagement and Commitment?

4.1.1. Heartware: Morale Breakers

| Themes | Supporting Sub-Themes with Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal—Institutional | Burnout from being overworked and emotional exhaustion (n = 94) |

|

| Lack of appreciation or support at work (n = 54) |

“The limelight was all [on the well-known Infectious Diseases institutions], minimal coverage of the daily struggles in a normal hospital setting…”

| |

| Disengagement (n = 12) |

“MC rate is high. it gets demoralising. There are days I wake up not wanting to do to work.”

| |

| Workplace stigma (n = 5) |

| |

| External—public and policy | Feeling stigmatized, discriminated against by the wider community (n = 17) |

“Want to move out. But noted agents/landlords/owners prefers non healthcare tenants. Some rents seems went high.”

|

| Calls for better pay and provisions for healthcare workers (n = 16) |

| |

| Frustration about public apathy (n = 7) |

| |

4.1.2. Heartware: Morale Boosters

| Themes | Supporting Sub-Themes with Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal—Institutional | Stoic acceptance to fight, adjust and hold the line (n = 138) |

|

| Motivated and inspired by strong leadership and supportive colleagues (n = 67) |

“And most of all, having out Team Leader […] who selflessly devoted [herself] to ensure that we healthcare workers are safe and sound […] I am beyond grateful. Working in this kind of Pandemic is much easier if you know that someone got your back.”

| |

| Pride in being healthcare workers–finding a sense of purpose in one’s work (n = 61) |

| |

| Appreciative of being thanked and supported at work (n = 16) |

| |

| Able to better connect with patients (n = 11) |

“This has enabled me to better appreciate the difficulties that my patients experience in building boundaries and allowed me to be more compassionate towards their struggles in staying at home…This realisation has enabled me to be more understanding and empathetic towards them, allowing us to build a stronger therapeutic alliance towards change.”

| |

| External—public andpolicy | Gaining a greater sense of solidarity with the public (n = 19) |

“We stand as One as this is our Home. If we dun [sic] fight and overcome this, who will?”

|

| Pride and feeling appreciated by public recognition (n = 7) |

“Appreciation sponsorships (even if it is just a free drink) motivates us to continue caring for the public.”

| |

4.2. What Barriers and Enablers Were Experienced That Affected Operational Safety and Functioning?

4.2.1. Hardware: Barriers to Operational Safety and Functioning

| Themes | Supporting Sub-Themes with Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal—Institutional | Sub-optimal segregation strategies within wards (n = 220) |

“[…] Staggering work hours and work from home arrangements will be useful for [minimizing] contact between staff.”

|

| Need to improve case detection, triage and admissions criteria protocols (n = 87) |

| |

| Scope for better application of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE, n = 54) |

“All healthcare staff in the nation should be already mask-fitted with N95 in advance and not to be done at last minute.”

“As a staff involved in entrance screening, no face shield given, I felt we had to just count our blessings of not getting infected.”

| |

| Duress of rapid, enforced infection control measures and relaxed staffing influx (n = 47) |

“On my First Day of deployment [to migrant worker dormitories in tentage areas]…I experienced a terrible headache from wearing the face shield […]. Wearing a full set of PPE under such conditions was unbearable. One of my colleagues vomited from the extreme heat.”

| |

| Need to enhance environmental cleaning (n = 29) |

| |

| Demand for training on how to be prepared during an outbreak (n = 8) |

| |

| Stepping up internal communication (n = 7) |

| |

| External—public andpolicy | Challenges of public health communication strategy (n = 27) |

|

| External parties’ failure to acknowledge unique challenges faced by healthcare workers (n = 2) |

| |

4.2.2. Hardware: Enablers to Operational Safety and Functioning

| Themes | Supporting Sub-Themes with Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal—Institutional | Timely and well-planned-for provision of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for front-liners (n = 41) |

“I feel blessed. I have proper PPE and a healthy body to take care of the patients.”

|

| In praise of other fast-enacted adaptive strategies that worked (n = 25) |

| |

| External—public andpolicy | Political legitimacy to mitigation initiatives and trust gained through inter-agency collaborations (n = 38) |

|

| Appreciation of being able to rely on lessons learnt from previous outbreaks (n = 18) |

| |

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation for Theory and Practice

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heath, C.; Sommerfield, A.; von Ungern-Sternberg, B.S. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, S.; Lydon, S.; Byrne, D.; Madden, C.; Connolly, F.; O’Connor, P. A systematic review of interventions to foster physician resilience. Postgrad. Med. J. 2018, 94, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bcheraoui, C.; Weishaar, H.; Pozo-Martin, F.; Hanefeld, J. Assessing COVID-19 through the lens of health systems’ preparedness: Time for a change. Glob. Health 2020, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.J.R.; Pena, L. Collapse of the public health system and the emergence of new variants during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. One Health 2021, 13, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.M.; Thampi, S.; Lewin, B.; Lim, T.J.D.; Rippin, B.; Wong, W.H.; Agrawal, R.V. Battling COVID-19: Critical care and peri-operative healthcare resource management strategies in a tertiary academic medical centre in Singapore. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen-Crowe, B.; Sutherland, M.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. A Closer Look into Global Hospital Beds Capacity and Resource Shortages During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 260, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar de Pablo, G.; Vaquerizo-Serrano, J.; Catalan, A.; Arango, C.; Moreno, C.; Ferre, F.; Shin, J.I.; Sullivan, S.; Brondino, N.; Solmi, M.; et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wei, J.; Zhu, H.; Duan, Y.; Geng, W.; Hong, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, B. A Study of Basic Needs and Psychological Wellbeing of Medical Workers in the Fever Clinic of a Tertiary General Hospital in Beijing during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagni, M.; Maiorano, T.; Giostra, V.; Pajardi, D. Coping With COVID-19: Emergency Stress, Secondary Trauma and Self-Efficacy in Healthcare and Emergency Workers in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, M.; Murray, E.; Christian, M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.; Ripp, J.; Trockel, M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety among Health Care Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, N.W.S.; Lee, G.K.H.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Ngiam, N.J.H.; Yeo, L.L.L.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmed Khan, F.; Napolean Shanmugam, G.; et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashino, Y.; Utsugi-Ozaki, M.; Feldman, M.D.; Fukuhara, S. Hope modified the association between distress and incidence of self-perceived medical errors among practicing physicians: Prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De los Santos, J.A.A.; Labrague, L.J. The impact of fear of COVID-19 on job stress, and turnover intentions of frontline nurses in the community: A cross-sectional study in the Philippines. Traumatology 2021, 27, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Coker, R.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M.; Leo, Y.S.; Chow, A.; Lim, P.L.; Tan, Q.; Chen, M.I.C.; Hildon, Z.J.L. Mapping infectious disease hospital surge threats to lessons learnt in Singapore: A systems analysis and development of a framework to inform how to DECIDE on planning and response strategies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.K.; Rudge, J.W.; Coker, R. Health systems’ “surge capacity”: State of the art and priorities for future research. Milbank Q. 2013, 91, 78–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, A.F.; Wild, C.; Law, J. The Barrow-in -Furness legionnaires’ outbreak: Qualitative study of the hospital response and the role of the major incident plan. Emerg. Med. J. 2005, 22, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuguyo, O.; Kengne, A.P.; Dandara, C. Singapore COVID-19 Pandemic Response as a Successful Model Framework for Low-Resource Health Care Settings in Africa? OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2020, 24, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Lie, S.A.; Ong, Y.Y. Hardware versus heartware: The need to address psychological well-being among operating room staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Anesthesia 2020, 65, 109891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, K.; Remes, P.; Rugabo, J.; Van Rossem, R.; Temmerman, M. Rwandan young people’s perceptions on sexuality and relationships: Results from a qualitative study using the ‘mailbox technique’. Sahara J. 2014, 11, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddington, K. Using diaries to explore the characteristics of work-related gossip: Methodological considerations from exploratory multimethod research. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D. Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 634–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Statistics. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/statistics (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Chan, L.G.; Tan, P.L.L.; Sim, K.; Tan, M.Y.; Goh, K.H.; Su, P.Q.; Tan, A.K.H.; Lee, E.S.; Tan, S.Y.; Lim, W.P.; et al. Psychological impact of repeated epidemic exposure on healthcare workers: Findings from an online survey of a healthcare workforce exposed to both SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and COVID-19. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, D.H. The application of systems thinking in health: Why use systems thinking? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foo, C.D.; Grepin, K.A.; Cook, A.R.; Hsu, L.Y.; Bartos, M.; Singh, S.; Asgari, N.; Teo, Y.Y.; Heymann, D.L.; Legido-Quigley, H. Navigating from SARS-CoV-2 elimination to endemicity in Australia, Hong Kong, New Zealand, and Singapore. Lancet 2021, 398, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangachari, P.; Woods, J.L. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during covid-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontalay, A.; Suksatan, W.; Prabsangob, K.; Sadang, J.M. Healthcare workers’ burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative systematic review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ting, C.; Chan, A.Y.; Chan, L.G.; Hildon, Z.J.-L. “Well, I Signed Up to Be a Soldier; I Have Been Trained and Equipped Well”: Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during COVID-19 Organizational Changes in Singapore, from the First Wave to the Path towards Endemicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042477

Ting C, Chan AY, Chan LG, Hildon ZJ-L. “Well, I Signed Up to Be a Soldier; I Have Been Trained and Equipped Well”: Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during COVID-19 Organizational Changes in Singapore, from the First Wave to the Path towards Endemicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042477

Chicago/Turabian StyleTing, Celene, Alyssa Yenyi Chan, Lai Gwen Chan, and Zoe Jane-Lara Hildon. 2022. "“Well, I Signed Up to Be a Soldier; I Have Been Trained and Equipped Well”: Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during COVID-19 Organizational Changes in Singapore, from the First Wave to the Path towards Endemicity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042477

APA StyleTing, C., Chan, A. Y., Chan, L. G., & Hildon, Z. J.-L. (2022). “Well, I Signed Up to Be a Soldier; I Have Been Trained and Equipped Well”: Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during COVID-19 Organizational Changes in Singapore, from the First Wave to the Path towards Endemicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042477