Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

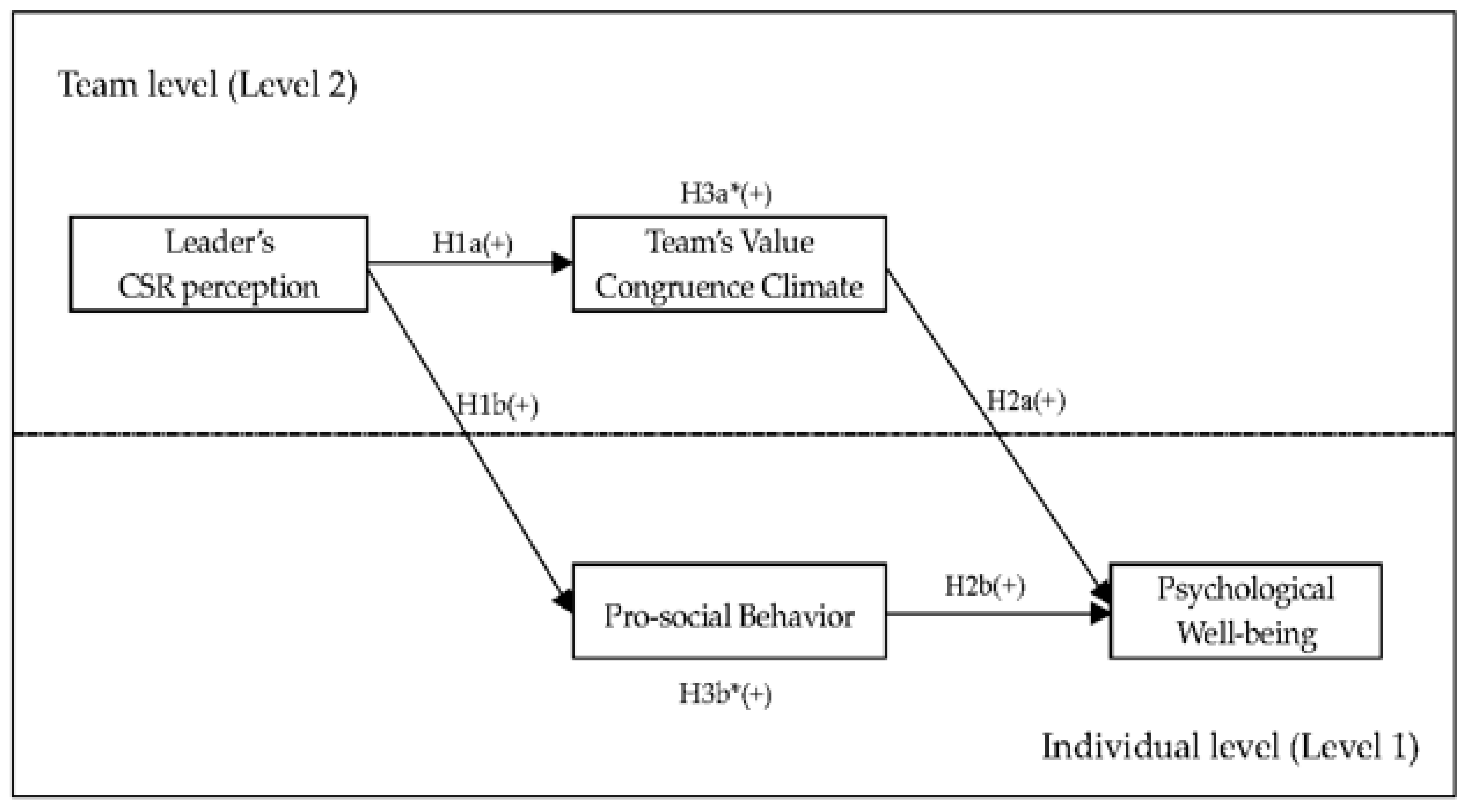

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Team Leader’s CSR Perception, Team’s Value Congruence Environment, and Team Members’ Pro-Social Behaviors

2.2. Team’s Value Congruence Environment and Team Members’ Prosocial Behaviors and Psychological Well-Being

2.3. Mediating Effect of the Team’s Value Congruence Environment and Team Members’ Prosocial Behaviors

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Leader’s CSR Perception

3.2.2. Value Congruence Environment

3.2.3. Pro-Social Behaviors

3.2.4. Psychological Well-Being

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howard, B. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Happer & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing: An Integrative Framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Corporate Citizenship: Cultural Antecedents and Business Benefits. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics Training and Businesspersons? Perceptions of Organizational Ethics. J. Bus. Ethic 2004, 52, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pantani, D.; Peltzer, R.; Cremonte, M.; Robaina, K.; Babor, T.; Pinsky, I. The marketing potential of corporate social responsibility activities: The case of the alcohol industry in Latin America and the Caribbean. Addiction 2017, 112, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Relationship Marketing of Services—Growing Interest, Emerging Perspectives. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, W.R.; Berry, L.L. Guidelines for the advertising of services. Bus. Horiz. 1981, 24, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilly, M.C.; Wolfinbarger, M. Advertising’s internal audience. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 404–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.L. Addressing a theoretical problem by reorienting the corporate social performance model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, D.D. Psychological Perspectives on Ethical Behavior and Decision Making; Information Age Publishing, INC.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Elsbach, K.D. Us versus Them: The Roles of Organizational Identification and Disidentification in Social Marketing Initiatives. J. Public Policy Mark. 2002, 21, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Miyazaki, A.D.; Taylor, K.A. The Influence of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Choice: Does One Good Turn Deserve Another? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Socially responsible organizational buying: Environmental concern as a noneconomic buying criterion. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A. Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: The emergence of corporate environmentalism as market strategy. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How Corporate Social Responsibility Influences Organizational Commitment. J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.D.; Dunford, B.B.; Alge, B.J.; Jackson, C.L. Corporate Social Responsibility, Ethical Leadership, and Trust Propensity: A Multi-Experience Model of Perceived Ethical Climate. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 137, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.-T.; Kim, N.-M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee–Company Identification. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P.; Baruch, Y.; Shih, W.-C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Performance: The Mediating Role of Team Efficacy and Team Self-Esteem. J. Bus. Ethic 2011, 108, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wright, P.M. On becoming a strategic partner: The role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 37, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macduffie, J.P.; Pfeffer, J. Competitive Advantage Through People: Unleashing the Power of the Work Force. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F. The impact of superior–subordinate relationships on the commitment, job satisfaction, and performance of virtual workers. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Graen, G. Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 451–465. [Google Scholar]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and employee reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, C.R.; Day, D.V. Meta-Analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Bynum, B.H.; Piccolo, R.F.; Sutton, A.W. Person-Organization Value Congruence: How Transformational Leaders Influence Work Group Effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Soc. Indic. Res. 1994, 31, 103–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munz, D.C.; Kohler, J.M.; Greenberg, C.I. Effectiveness of a Comprehensive Worksite Stress Management Program: Combining Organizational and Individual Interventions. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, I.; Taylor, P.; Johnson, S.; Cooper, C.; Cartwright, S.; Robertson, S. Work environments, stress, and productivity: An examination using ASSET. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, R.D.; Karasick, B.W. The effects of organizational climate on managerial job performance and job satisfaction. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1973, 9, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. Res. Corp. Soc. Perform. Policy 1987, 9, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The Organizational Bases of Ethical Work Climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.C.; Burack, E.H. Organizational Culture and Human Resource Management. In Organizational Culture Inventory Leader’s Guide; Human Synergistics: Plymouth, MI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. Beliefs, Attitudes and Values: A Theory of Organization and Change; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Suar, D.; Khuntia, R. Influence of Personal Values and Value Congruence on Unethical Practices and Work Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 97, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Person–Organization Fit, Job Choice Decisions, and Organizational Entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Gulbovaitė, E. Expert Evaluation of Diagnostic Instrument for Personal and Organizational Value Congruence. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 136, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Gulbovaitė, E. Asmeninių ir organizacinių vertybių kongruencijos modelis. Vadyb. Moksl. Ir Stud. Kaimo Verslų Ir Jų Infrastruktūros Plėtrai 2012, 4, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Slusher, B.J.; Helmick, S.A.; Metzen, E.J. Perceived economic well-being: The relative impact of value concordance and resource adequacy. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Perceived Economic Well-Being; University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign: Urbana, IL, USA, 1983; pp. 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial Behavior: Multilevel Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brief, A.P.; Motowidlo, S.J. Prosocial organizational behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D. Prosocial Motivation: Is it ever Truly Altruistic? Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 20, 65–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darley, J.M.; Latane, B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 8, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. The Sweet Smell of. Helping: Effects of Pleasant Ambient Fragrance on Prosocial Behavior in Shopping Malls. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J. Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L. Metaphor in educational discourse. In Advances in Applied Linguistics; Continuum: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F. Understanding the Inner Nature of Low Self-Esteem: Uncertain, Fragile, Protective, and Conflicted. In Self-Esteem; Springer: Boston, MA. USA, 1993; pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L. The Structure of Psychological Well-being Revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Employees’ Weekend Activities and Psychological Well-Being via Job Stress: A Moderated Mediation Role of Recovery Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.; Thatcher, S.M. Identification in organizations: The role of self-concept orientations and identification motives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 516–538. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational Images and Member Identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; John, O.P.; Keltner, D.; Kring, A.M. Who attains social status? Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in social groups. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkenauer, C.; Meeus, W. How (pro-) social is the caring motive? Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Zmyj, N.; Buttelmann, D.; Carpenter, M.; Daum, M.M. The reliability of a model influences 14-month-olds’ imitation. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2010, 106, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-Cultural Research Methods. In Environment and Culture; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A.; Brown, S.W. Contact employees: Relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kirkman, B.L.; Kanfer, R.; Allen, D.; Rosen, B. A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 249–381. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, K.J.; Bliese, P.D.; Kozolowski, S.W.J.; Dansereau, F.; Gavin, M.B.; Griffin, M.A.; Hofmann, D.A.; James, L.R.; Yammarino, F.J.; Bligh, M.C. Multilevel analytical techniques: Commonalities, differences, and continuing questions. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 512–553. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, W.J.; Kim, H.-K. Servant Leadership and Customer Service Quality at Korean Hotels: Multilevel Organizational Citizenship Behavior as a Mediator. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.N. Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: Effects of work environment characteristics and intervening psychological processes. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Silver, S.R.; Randolph, W.A. Taking empowerment to the next level: A multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 332–349. [Google Scholar]

- Shmotkin, D. Subjective well-being as a function of age and gender: A multivariate look for differentiated trends. Soc. Indic. Res. 1990, 23, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, E.; Diener, E.; Fujita, F. Events and subjective well-being: Only recent events matter. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.; Wu, J.Y.W.; Wang, C.S.; Pan, L.H. Health-promoting Lifestyles and Psychological Distress Associated with Well-being in Community Adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, Ö.; Çağlayan, H.S.; Akandere, M. The Effect of Sports on the Psychological Well-being Levels of High School Students. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kylén, M.; Schmidt, S.M.; Iwarsson, S.; Haak, M.; Ekström, H. Perceived home is associated with psychological well-being in a cohort aged 67–70 years. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Servant Leadership and Creativity: A Study of the Sequential Mediating Roles of Psychological Safety and Employee Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, J.-H.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. The Effect of Perceived Supervisor–Subordinate Congruence in Honesty on Emotional Exhaustion: A Polynomial Regression Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) Individual (Level 1) Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| 1. | Gender | 1.35 | 0.48 | - | |||||||

| 2. | Age | 2.45 | 1.03 | −2.21 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. | Education | 2.58 | 0.90 | −0.19 | −0.20 ** | - | |||||

| 4. | Tenure | 8.84 | 8.43 | −0.31 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.06 | - | ||||

| 5. | Position | 2.22 | 1.16 | −0.32 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.50 ** | - | |||

| 6. | Job characteristic | 2.00 | 0.37 | −0.03 | 0.14 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.00 | −0.11 * | - | ||

| 7. | Prosocial behaviors | 3.66 | 0.55 | −0.15 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.06 | (0.92) | |

| 8. | Psychological well-being | 3.68 | 0.55 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.19 ** | 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.55 ** | (0.91) |

| (b) Team (Level 2) Variables | Mean | SD | ICC1 | ICC2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 1. | Team size | 4.82 | 1.62 | ||||||||

| 2. | Team tenure | 5.18 | 4.18 | 0.14 | |||||||

| 3. | Leader’s CSR perception | 3.77 | 0.55 | 0.17 | −0.12 | (0.94) | |||||

| 4. | Value congruence climate | 3.52 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.05 | −0.26 * | 0.54 *** | (0.91/0.87) | ||

| Variables | Prosocial Behaviors (PB) | Value Congruence Climate (VCC) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Fixed effect | Estimates | Estimates | Estimates |

| Individual Level | |||

| Intercept | 3.68 *** | 3.68 *** | |

| Gender | −0.02 | ||

| Age | 0.11 | ||

| Education | 0.10 | ||

| Group Level | |||

| Intercept | 1.86 *** | ||

| Team size | −0.04 * | 0.00 | |

| Team tenure | −0.00 | −0.02 ** | |

| Leader’s CSR perception (CSR) | 0.39 *** | 0.46 *** | |

| Random effect | Variancecomponent | Variancecomponent | Variancecomponent |

| Group-level variance(τ) | 0.3043 *** | 0.0515 *** | 0.0515 *** |

| Individual-level variance(σ2) | 0.4675 | 0.2020 | 0.2020 |

| Deviance | 516.96 | 494.29 | 494.29 |

| χ2 | 143.37 | 143.37 | |

| Variables | Psychological Well-being (PW) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Fixed effect | Estimates | Estimates | Estimates | Estimates |

| Individual Level | ||||

| Intercept | 3.69 *** | 3.69 *** | 2.58 *** | 1.77 *** |

| Gender | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.08 | |

| Age | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | |

| Education | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.00 | |

| Prosocial behaviors (PB) | 0.48 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.48 *** | |

| Group Level | ||||

| Team size | −0.02 | −0.02 ** | ||

| Team tenure | −0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Leader’s CSR perception (CSR) | 0.33 *** | 0.13 * | ||

| Value congruence climate (VCC) | 0.43 *** | |||

| Random effect | Variance component | Variance component | Variance component | Variance component |

| Group-level variance(τ) | 0.0755 *** | 0.0861 *** | 0.0567 *** | 0.0245 *** |

| Individual-level variance(σ2) | 0.2377 | 0.1906 | 0.1901 | 0.1910 |

| Deviance | 532.73 | 487.43 | 484.61 | 460.69 |

| χ2 | 212.3 | 156.64 | 103.75 | |

| Variables | Psychological Well-being (PW) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Fixed effect | Estimates | Estimates | Estimates |

| Intercept | 3.69 *** | 2.59 *** | 1.77 *** |

| Team size | −0.02 ** | −0.02 | |

| Team tenure | −0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Leader’s CSR perception (CSR) | 0.33 *** | 0.12 * | |

| Value congruence climate (VCC) | 0.43 *** | ||

| Random effect | Variance component | Variance component | Variance component |

| Individual-level variance (σ2) | 0.2377 | 0.2369 | 0.2379 |

| Group-level variance (τ) | 0.0755 *** | 0.0469 *** | 0.0145 *** |

| Change in variance (∆τ) | 0.0286 | 0.0324 | |

| Proportion of explained variance | 37.8% | 42.9% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, J.-G.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063607

Jeong J-G, Choi SB, Kang S-W. Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063607

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Jae-Geum, Suk Bong Choi, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2022. "Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063607

APA StyleJeong, J.-G., Choi, S. B., & Kang, S.-W. (2022). Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063607