1. Introduction

One of the measures adopted to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 is maintaining social distancing. During the pandemic, the Internet has been a particularly important channel for information [

1,

2], forcing people to increase their online activities and resulting in, among other things, dramatic growth in online commerce [

3,

4]. In China, 70% of consumers increased their online shopping for this reason [

4]. The ease with which members of Generation Z make use of technologies has had a considerable impact on the e-commerce strategies of companies worldwide [

5]. Thus, Chinese members of Generation Z are responsible for a significant portion of internet shopping transactions [

4,

6,

7]. Branding efforts have, accordingly, focused increasingly on efforts to develop a following within this demographic in the specific context of mobile commerce [

8].

In recent years, the widespread adoption of smartphones has contributed further to the popularity of online shopping [

7,

9]. As the number of individual consumers online has increased, researchers have concentrated on identifying factors that influence this kind of shopping [

3]. Several studies have analyzed the current trends in mobile shopping based on browsing and purchase data from online retailers, for instance, after launching a mobile app [

9,

10]. A key aspect of the study of mobile shopping behavior involves identifying factors that may influence purchase intention [

11]. The evidence suggests that considerations of efficiency and personal circumstances influence purchase intention as well as the perceived value of mobile shopping [

12].

Scholars are also paying attention to consumers’ brand identity, that is, their desire to express their personal identity through brand preferences [

13]. This research has taken into account, for instance, the effects of brands on the identity of groups of consumers [

14], the distinct meaning of various brands for individuals and groups [

15], the aesthetics and perceived uniqueness of brands [

16], and consumers’ attitudes toward particular brands [

17]. The concept of product aesthetics captures the self-expressive consideration of consumers’ choice of one set of products with which they feel greater affinity than another set [

18]. Accordingly, especially strong preferences for self-expression through brand choice are likely to be reflected in strong personal aesthetic preferences [

19]. In terms of self-expression, the key factor is a brand’s perceived uniqueness, in that preferences for self-expressive brands tend to correlate with perceptions of brand conspicuousness [

20] and, in turn, strengthen the behavioral outcomes of these preferences [

17].

Having been born into the digital world, the members of Generation Z have never known life without the Internet or smartphones [

21,

22]. It is often argued that, as a result, these individuals are more comfortable presenting a public self than the members of earlier generations [

6,

22,

23]. A key driver of the perspectives of Generation Z in this regard has been the use of smartphones to create online identities and narratives of individuals’ lives, a behavior that appeals to their sense of uniqueness and preference for personalized products and services [

24,

25]. In fact, the desire to manifest individual identity is central to the notion of brand identity for Generation Z users [

26].

Smartphones, as agents, allow users to share self-expression and identity but also have inherent attributes, in particular, the values and concepts associated with various brands [

27]. However, the research on smartphones and branding has, thus far, paid relatively little attention to the effect of hedonic experience on mobile consumer behavior. To help fill this gap in the research, we here provided fresh insights into consumers’ use of brands to express personal identity [

28,

29]. Extending the notion of brands as a means of self-expression in various contexts—for instance, as identity signals [

13,

16,

30]—we described shifts in the mobile consumer behavior of members of China’s Generation Z that are likely to persist through and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we investigated the role of brands in consumers’ drive to engage in self-expression in order to explore (1) the effect of the mobile hedonic experience on perceived aesthetics, brand conspicuousness, and, thereby, brand identity and associated behavioral changes in general and (2) theories regarding the use of brands for self-expression.

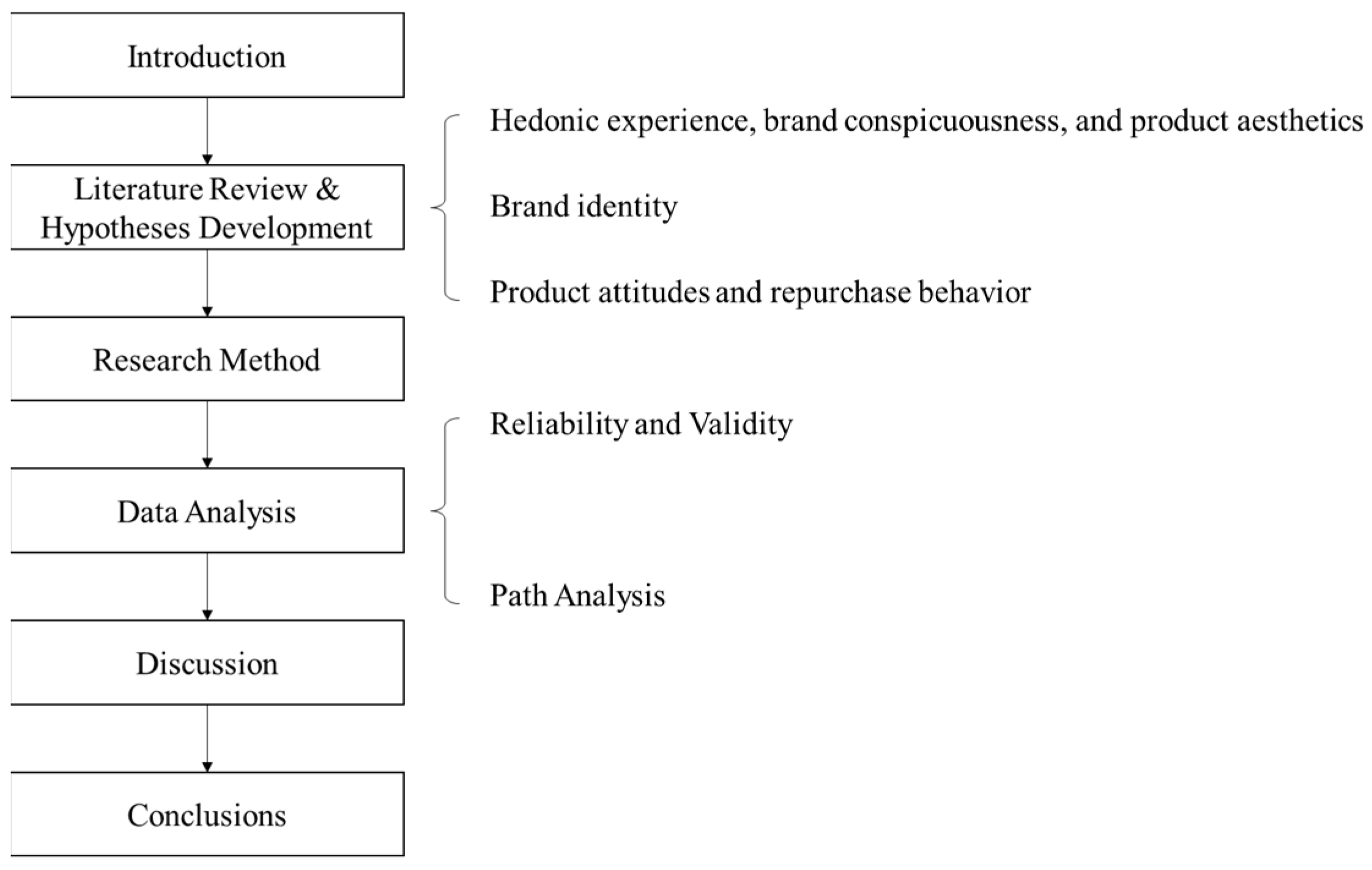

The aim of this study, then, was to develop an integrated model linking hedonic experience to brand conspicuousness, brand identity, and associated behavior in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as shown in

Figure 1. In what follows, we discuss relevant concepts and theories and describe the development of our hypotheses in

Section 2. We explain the research design in

Section 3 and, in

Section 4, present an analysis of the data indicating that hedonic experience was significantly related to brand conspicuous, perceived aesthetic congruity, and, in turn, brand identity and product attitude. In

Section 5 and

Section 6, we discuss the results, theoretical contributions, and practical implications of our study.

5. Results and Discussion

In this study, we examined the effects of hedonic experience on brand conspicuousness, product aesthetics, brand identity, and associated behavior reactions in the specific context of mobile shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that hedonic experience played an essential role in signaling brand conspicuousness and product aesthetics, which in turn promoted brand identity and associated behavioral reactions.

The findings presented here contribute to the understanding of the role of hedonic experience, product attitude, brand conspicuousness, and brand identity in mobile shopping. In the first place, though previous research showing that brand attitude positively influenced behavioral intention has attracted considerable interest, the focus of this interest has been on offline consumption. Thus, for instance, several recent studies [

25,

76,

77] suggested that consumers are susceptible to online information and cues related to social identification that could influence purchase behavior, but the authors discussed the findings from the limited perspective of consumers’ social identification, which is to say, without reference to the specific effects of product attitude and brand identity. In designing the present study, we took into account the results of earlier research into online consumer behaviors. We found that brand identity did, in fact, influence repurchase intention and subsequent assessments of value.

From the perspective of the theory of consumer behavior, we shed new light on the effectiveness of purchase intention in relation to hedonic experience with particular attention to brand conspicuousness and brand identity [

78,

79]. As expected, a favorable product attitude encouraged the repeated purchase of a brand’s products [

80]. As individuals advance in age and in their careers, they usually become more likely to purchase known brands. The members of Generation Z tend to prefer communication through social media platforms accessed on various electronic devices and, likewise, to conduct much or even most of their shopping online [

80]. Moreover, because these consumers tend to be well-informed and eager to acquire new information and control their lives and futures, they tend to be much less loyal to retailers than, for instance, Millennials [

80]. Thus, this study contributes to the literature on repurchase intention by offering preliminary evidence for the impact of brand conspicuousness and brand identity on repurchase behavior [

81,

82].

We focused on Generation Z because its members have typically been especially prone to establish brand identity in terms of such attributes of products such as aesthetics, consistency with personal taste and style, pleasure, happiness, and/or uniqueness [

82,

83]. For members of Generation Z in particular, self-perception is determined in part by the groups to which they belong and with which they identify [

83]. Several scholars [

25,

32,

76] have pointed out that these consumers have had access to a wide range of options to satisfy their needs through sharing and showing their lives. In addition, when choosing products, members of this generation rely especially heavily on design and aesthetics, regardless of the type of retailer, physical or online, from which they are making a purchase [

82]. Among the world’s countries, China has the largest population of members of Generation Z [

21]. Most are likely to achieve higher levels of education and income than the members of previous generations and are thus more likely to consume brands with established international reputations. Aligned with the earlier research on which it built, the results of the present study are sufficiently robust to be generalized to other regions such as Japan, Korea, and Thailand [

84]. One way in which future researchers could build on these findings is by testing the theoretical framework via conducting surveys in other developing countries and performing cross-national comparisons to contribute to a universal theory of branding [

73]. In addition, as mentioned, work is needed to develop multidimensional scales for measuring brand identification in isolation from other factors. Therefore, marketers have opportunities to use hedonic or aesthetic appeals in their strategies. Furthermore, this study provides insights that marketing managers for multinational brands can leverage to enhance their engagement with this new generation of digital native customers.

We acknowledge that the research presented here is subject to certain limitations. To begin with, regarding the methodology, the number of participants in the survey was relatively small and included only relatively young Chinese consumers. Increasing the number of participants and including consumers from other countries would yield more diverse perceptions of and deeper insights into brands and mobile shopping. Further, we did not take into account the impact of the latest mobile technology on the evolution of consumers’ mobile shopping behavior. In addition, the gender ratio was not balanced. Prior research has suggested that gender as well as age may exert less influence on consumers’ attitudes and reactions than has generally been reported [

85]. Accordingly, a more balanced gender and age sample would increase the generalizability of future similar studies. Last, though a pilot study was introduced to keep the clarity and consistency of surveys, the adaptation of the scales could potentially influence the validity of the current measurements. Future studies should try to revalidate the current findings.

6. Conclusions

With the expansion of mobile technologies, online customers have been enjoying and, indeed, demanding a wide range of choices at highly competitive prices when selecting products and services. Therefore, retailers are facing increasing pressure to ensure that the mobile shopping experience is pleasurable—even as consumers become increasingly critical, less brand-loyal, and, generally, harder to please. In this sense, the insights into mobile shopping, hedonic shopping experience, brand identity, and consumer behavior offered here can help marketers to understand the conspicuous consumption of brands and identify features that customers value, areas for improvement, especially under circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, that encourage online commerce. Our findings provide a starting point for improving the effectiveness of online retailing through an emphasis on hedonic experience. Thus, we found that hedonic experience played an essential role in signaling brand conspicuousness and product aesthetics, which, in turn, promote brand identity and behaviors associated with it.