Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Background and Rationale

- (1)

- How many and what types of patient-centered interventions have been examined or designed to promote the utilization of physical health care systems for people with a SMI?

- (2)

- Which studies report positive outcomes on the utilization behavior, as well as on physical health measures, and what are promising concepts for the broader implementation into health care systems?

- (3)

- What are current research gaps regarding this topic?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

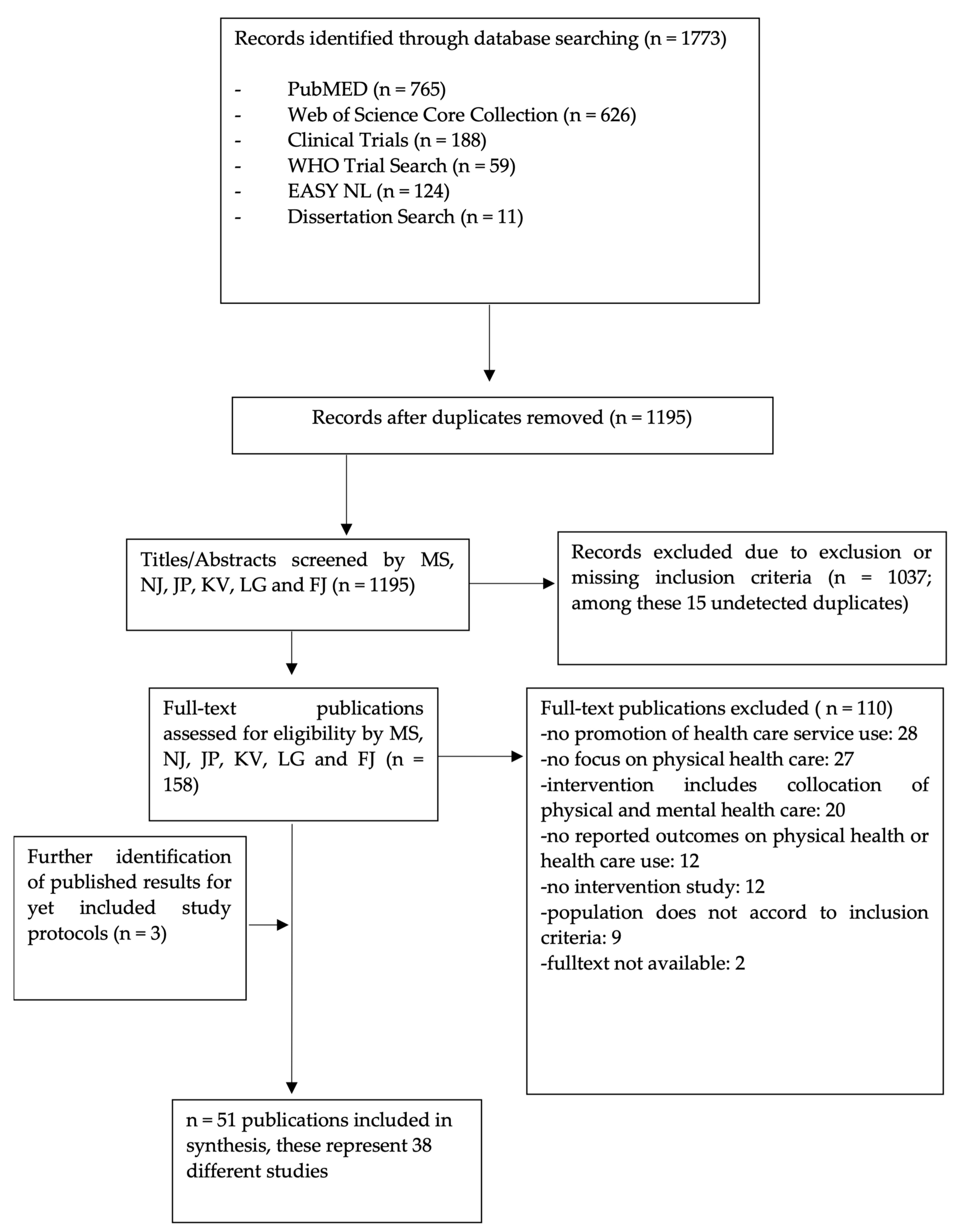

3.1. Study Selection and Exclusion Process: Number of Identified Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Interventions, Background, and Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Available Studies on the Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care in SMI

4.2. Implementation of the Access and Use Promotion: Promising Concepts and Major Gaps

4.3. Research Gaps and Future Research Directions

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in Mental Disorders and Global Disease Burden Implications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, S.J.; Burgers, J.; Friedberg, M.; Rosenthal, M.B.; Leape, L.; Schneider, E. Defining and Measuring Integrated Patient Care: Promoting the Next Frontier in Health Care Delivery. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2011, 68, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.; Planner, C.; Gask, L.; Hann, M.; Knowles, S.; Druss, B.; Lester, H. Collaborative Care Approaches for People with Severe Mental Illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 11, CD009531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthappu, M.; Hasan, A.; Zeltner, T. Enablers and Barriers in Implementing Integrated Care. Health Syst. Reform 2015, 1, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, D.; Coppleson, D.; Travaglia, J. Factors Supporting the Implementation of Integrated Care between Physical and Mental Health Services: An Integrative Review. J. Interprof. Care 2021, 36, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.; Richard, L.; Gunter, K.; Cunningham, R.; Hamer, H.; Lockett, H.; Wyeth, E.; Stokes, T.; Burke, M.; Green, M.; et al. A Systematic Scoping Review of Interventions to Integrate Physical and Mental Healthcare for People with Serious Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 128, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, N.; Destoop, M.; Dom, G. Organization of Community Mental Health Services for Persons with a Severe Mental Illness and Comorbid Somatic Conditions: A Systematic Review on Somatic Outcomes and Health Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druss, B.G.; Marcus, S.C.; Campbell, J.; Cuffel, B.; Harnett, J.; Ingoglia, C.; Mauer, B. Medical Services for Clients in Community Mental Health Centers: Results from a National Survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coventry, P.A.; Young, B.; Balogun-Katang, A.; Taylor, J.; Brown, J.V.E.; Kitchen, C.; Kellar, I.; Peckham, E.; Bellass, S.; Wright, J.; et al. Determinants of Physical Health Self-Management Behaviours in Adults with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 723962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romain, A.J.; Bernard, P.; Akrass, Z.; St-Amour, S.; Lachance, J.-P.; Hains-Monfette, G.; Atoui, S.; Kingsbury, C.; Dubois, E.; Karelis, A.D.; et al. Motivational Theory-Based Interventions on Health of People with Several Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 222, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehily, C.; Hodder, R.; Bartlem, K.; Wiggers, J.; Wolfenden, L.; Dray, J.; Bailey, J.; Wilczynska, M.; Stockings, E.; Clinton-McHarg, T.; et al. The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Preventive Care Provision for Chronic Disease Risk Behaviours in Mental Health Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 19, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabassa, L.J.; Ezell, J.M.; Lewis-Fernández, R. Lifestyle Interventions for Adults with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Literature Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010, 61, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronaldson, A.; Elton, L.; Jayakumar, S.; Jieman, A.; Halvorsrud, K.; Bhui, K. Severe Mental Illness and Health Service Utilisation for Nonpsychiatric Medical Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M.J.; Jones, M.; Bressington, D.; Jones, A.; Nolan, F.; Muyambi, K.; Gillam, M.; Gray, R. The Association between Community Mental Health Nursing and Hospital Admissions for People with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramanuj, P.; Ferenchik, E.; Docherty, M.; Spaeth-Rublee, B.; Pincus, H.A. Evolving Models of Integrated Behavioral Health and Primary Care. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, M.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M.; Milton, A.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Harrison-Stewart, B.; Yesufu-Udechuku, A.; Kendall, T.; Johnson, S. Self-Management Interventions for People with Severe Mental Illness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2019, 214, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, M.; Dalton, J.; Harden, M.; Street, A.; Parker, G.; Eastwood, A. Integrated Care to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness: A Mapping Review of the Recent Evidence on Barriers, Facilitators and Evaluations. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, K.A.; Daumit, G.L.; Stone, E.; McGinty, E.E. Physical Health Outcomes and Implementation of Behavioural Health Homes: A Comprehensive Review. Int. Rev. Psychiatry Abingdon Engl. 2018, 30, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, E.; Kho, D.; Docherty, J.P. Use of Technology for Care Coordination Initiatives for Patients with Mental Health Issues: A Systematic Literature Review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 2337–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kronenberg, C.; Doran, T.; Goddard, M.; Kendrick, T.; Gilbody, S.; Dare, C.R.; Aylott, L.; Jacobs, R. Identifying Primary Care Quality Indicators for People with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, e519–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, K.L.; Naslund, J.A.; DiNapoli, E.A.; Bruce, M.L.; Bartels, S.J. Systematic Review of Integrated General Medical and Psychiatric Self-Management Interventions for Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, M.; Dalton, J.; Harden, M.; Street, A.; Parker, G.; Eastwood, A. Integrated Care to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness: A Rapid Review. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2016, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, K.; Choi, J.S.; Choi, E.; Nieman, C.L.; Joo, J.H.; Lin, F.R.; Gitlin, L.N.; Han, H.-R. Effects of Community-Based Health Worker Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Care Among Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, e3–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyeres, M.; McCalman, J.; Tsey, K.; Kinchin, I. The Complexity of Health Service Integration: A Review of Reviews. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Happell, B.; Ewart, S.B.; Platania-Phung, C.; Stanton, R. Participative Mental Health Consumer Research for Improving Physical Health Care: An Integrative Review: Consumer Research and Physical Health. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 25, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Galletly, C.; Castle, D.; Platania-Phung, C.; Stanton, R.; Scott, D.; McKenna, B.; Millar, F.; Liu, D.; Browne, M.; et al. Scoping Review of Research in Australia on the Co-Occurrence of Physical and Serious Mental Illness and Integrated Care. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siantz, E.; Aranda, M.P. Chronic Disease Self-Management Interventions for Adults with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, J.C.; Niazi, S.K.; Rundell, J.R.; Sharpe, M.; Katon, W.J. Essential Articles on Collaborative Care Models for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders in Medical Settings: A Publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics 2014, 55, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Platania-Phung, C.; Scott, D. A Systematic Review of Nurse Physical Healthcare for Consumers Utilizing Mental Health Services. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Pickett, S.; Batia, K.; Michaels, P.J. Peer Navigators and Integrated Care to Address Ethnic Health Disparities of People with Serious Mental Illness. Soc. Work Public Health 2014, 29, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hasselt, F.M.; Krabbe, P.F.M.; van Ittersum, D.G.; Postma, M.J.; Loonen, A.J.M. Evaluating Interventions to Improve Somatic Health in Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013, 128, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, D.W.; Cunningham, N.T.; Slubicki, M.N.; McDuffie, J.R.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Nagi, A.; Williams, J.W.J. An Evidence Synthesis of Care Models to Improve General Medical Outcomes for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e754–e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woltmann, E.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Perron, B.; Georges, H.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Bauer, M.S. Comparative Effectiveness of Collaborative Chronic Care Models for Mental Health Conditions Across Primary, Specialty, and Behavioral Health Care Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranter, S.; Irvine, F.; Collins, E. Innovations Aimed at Improving the Physical Health of the Seriously Mentally Ill: An Integrative Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blythe, J.; White, J. Role of the Mental Health Nurse towards Physical Health Care in Serious Mental Illness: An Integrative Review of 10 Years of UK Literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 21, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghe, N.; De Maeseneer, J.; Maes, L.; Van Heeringen, C.; Annemans, L. Perceptions of Mental Health Nurses and Patients about Health Promotion in Mental Health Care: A Literature Review: Health Promotion in Mental Health Care. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.J.; Perkins, D.A.; Fuller, J.D.; Parker, S.M. Shared Care in Mental Illness: A Rapid Review to Inform Implementation. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2011, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawrence, D.; Kisely, S. Review: Inequalities in Healthcare Provision for People with Severe Mental Illness. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerimele, J.M.; Strain, J.J. Integrating Primary Care Services into Psychiatric Care Settings: A Review of the Literature. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 12, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druss, B.G.; von Esenwein, S.A. Improving General Medical Care for Persons with Mental and Addictive Disorders: Systematic Review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2006, 28, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E.E.; Baller, J.; Azrin, S.T.; Juliano-Bult, D.; Daumit, G.L. Interventions to Address Medical Conditions and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Persons with Serious Mental Illness: A Comprehensive Review. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 42, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Schreiber, G.; Haupt, C.C. Methodische Anleitung für Scoping Reviews (JBI-Methodologie). Z. Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Im Gesundh. 2019, 143, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strunz, M.; Jiménez, N.; Gregorius, L.; Hewer, W.; Pollmanns, J.; Viehmann, K.; Jacobi, F. Interventions to Promote Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness—A Scoping Review Protocol. OSF 2022, 23, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Erhart, M.; Hewer, W.; Loeffler, L.A.; Jacobi, F. Mortality and Medical Comorbidity in the Severely Mentally Ill. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 2019, 116, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, F.; Grafiadeli, R.; Volkmann, H.; Schneider, I. Krankheitslast der Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung: Krankheitskosten, somatische Komorbidität und Mortalität. Nervenarzt 2021, 92, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeft, T.J.; Fortney, J.C.; Patel, V.; Unützer, J. Task-Sharing Approaches to Improve Mental Health Care in Rural and Other Low-Resource Settings: A Systematic Review: Task-Sharing Rural Mental Health. J. Rural Health 2018, 34, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinho, S.; Sampaio, R. Behaviour Change Interventions in Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimer, B.K.; Glanz, K.; Rasband, G. Searching for Evidence about Health Education and Health Behavior Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2001, 28, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, A.; Bhat, C.; Gunzler, D.; Cassidy, K.; Thomas, C.; McCormick, R.; Dawson, N.V.; Sajatovic, M. Associations among Comorbid Anxiety, Psychiatric Symptomatology, and Diabetic Control in a Population with Serious Mental Illness and Diabetes: Findings from an Interventional Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2018, 53, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos, G.S.; Kiosses, D.N.; Sirey, J.A.; Kanellopoulos, D.; Seirup, J.K.; Novitch, R.S.; Ghosh, S.; Banerjee, S.; Raue, P.J. Untangling Therapeutic Ingredients of a Personalized Intervention for Patients with Depression and Severe COPD. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 22, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aragonès, E.; Lluís Piñol, J.; Caballero, A.; López-Cortacans, G.; Casaus, P.; Maria Hernández, J.; Badia, W.; Folch, S. Effectiveness of a Multi-Component Programme for Managing Depression in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. The INDI Project. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, S.J.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Rolin, S.A.; Hendrick, D.C.; Naslund, J.A.; Faber, M.J. Activating Older Adults with Serious Mental Illness for Collaborative Primary Care Visits. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartels, S.J.; Pratt, S.I.; Mueser, K.T.; Forester, B.P.; Wolfe, R.; Cather, C.; Xie, H.; McHugo, G.J.; Bird, B.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of a Randomized Trial of Integrated Skills Training and Preventive Healthcare for Older Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 22, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartels, S.J.; Pratt, S.I.; Mueser, K.T.; Naslund, J.A.; Wolfe, R.S.; Santos, M.; Xie, H.; Riera, E.G. Integrated IMR for Psychiatric and General Medical Illness for Adults Aged 50 or Older with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battersby, M.; Kidd, M.R.; Licinio, J.; Aylward, P.; Baker, A.; Ratcliffe, J.; Quinn, S.; Castle, D.J.; Zabeen, S.; Fairweather-Schmidt, A.K.; et al. Improving Cardiovascular Health and Quality of Life in People with Severe Mental Illness: Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. Trials 2018, 19, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjorkman, T.; Hansson, L. How Does Case Management for Long-Term Mentally Ill Individuals Affect Their Use of Health Care Services? An 18-Month Follow-up of 10 Swedish Case Management Services. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2000, 54, 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, M.B.; Hennessy, M.; Eisenberg, M.M. Increasing Quality of Life and Reducing HIV Burden: The PATH+ Intervention. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broughan, J.; McCombe, G.; Lim, J.; O’Keeffe, D.; Brown, K.; Clarke, M.; Corcoran, C.; Hanlon, D.; Kelly, N.; Lyne, J.; et al. Keyworker Mediated Enhancement of Physical Health in Patients with First Episode Psychosis: A Feasibility/Acceptability Study. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 16, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabassa, L.J.; Manrique, Y.; Meyreles, Q.; Camacho, D.; Capitelli, L.; Younge, R.; Dragatsi, D.; Alvarez, J.; Lewis-Fernández, R. Bridges to Better Health and Wellness: An Adapted Health Care Manager Intervention for Hispanics with Serious Mental Illness. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2018, 45, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chwastiak, L.A.; Luongo, M.; Russo, J.; Johnson, L.; Lowe, J.M.; Hoffman, G.; McDonell, M.G.; Wisse, B. Use of a Mental Health Center Collaborative Care Team to Improve Diabetes Care and Outcomes for Patients with Psychosis. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cook, J.A.; Jonikas, J.A.; Burke-Miller, J.K.; Hamilton, M.; Powell, I.G.; Tucker, S.J.; Wolfgang, J.B.; Fricks, L.; Weidenaar, J.; Morris, E.; et al. Whole Health Action Management: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Peer-Led Health Promotion Intervention. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumit, G.L.; Dalcin, A.T.; Dickerson, F.B.; Miller, E.R.; Evins, A.E.; Cather, C.; Jerome, G.J.; Young, D.R.; Charleston, J.B.; Gennusa, J.V., III; et al. Effect of a Comprehensive Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Intervention in Persons with Serious Mental Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e207247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druss, B.G.; Singh, M.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Glick, G.E.; Tapscott, S.; Tucker, S.J.; Lally, C.A.; Sterling, E.W. Peer-Led Self-Management of General Medical Conditions for Patients with Serious Mental Illnesses: A Randomized Trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druss, B.G.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Compton, M.T.; Rask, K.J.; Zhao, L.; Parker, R.M. A Randomized Trial of Medical Care Management for Community Mental Health Settings: The Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Druss, B.G.; Zhao, L.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Bona, J.R.; Fricks, L.; Jenkins-Tucker, S.; Sterling, E.; Diclemente, R.; Lorig, K. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: A Peer-Led Intervention to Improve Medical Self-Management for Persons with Serious Mental Illness. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 118, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldberg, R.W.; Dickerson, F.; Lucksted, A.; Brown, C.H.; Weber, E.; Tenhula, W.N.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Dixon, L.B. Living Well: An Intervention to Improve Self-Management of Medical Illness for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, D.E.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Lai, Z.; Post, E.P.; Bowersox, N.W.; Mezuk, B.; Schumacher, K.; Bramlet, M.; Welsh, D.E.; Bauer, M.S. Design and Rationale of a Randomized Controlled Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Risk for Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2012, 33, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.V.; Hjorth, P.; Kristiansen, C.B.; Vandborg, K.; Gustafsson, L.N.; Munk-Jørgensen, P. Reducing Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Non-Selected Outpatients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2016, 62, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happell, B.; Curtis, J.; Banfield, M.; Goss, J.; Niyonsenga, T.; Watkins, A.; Platania-Phung, C.; Moon, L.; Batterham, P.; Scholz, B.; et al. Improving the Cardiometabolic Health of People with Psychosis: A Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial of the Physical Health Nurse Consultant Service. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2018, 73, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happell, B.; Stanton, R.; Hoey, W.; Scott, D. Cardiometabolic Health Nursing to Improve Health and Primary Care Access in Community Mental Health Consumers: Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Stanton, R.; Scott, D. Utilization of a Cardiometabolic Health Nurse—A Novel Strategy to Manage Comorbid Physical and Mental Illness. J. Comorbidity 2014, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illinois Institute of Technology Peer Navigators for the Health and Wellness of People with Psychiatric Disabilities. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05018351 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Jakobsen, A.S.; Speyer, H.; Nørgaard, H.C.B.; Karlsen, M.; Birk, M.; Hjorthøj, C.; Mors, O.; Krogh, J.; Gluud, C.; Pisinger, C.; et al. Effect of Lifestyle Coaching versus Care Coordination versus Treatment as Usual in People with Severe Mental Illness and Overweight: Two-Years Follow-up of the Randomized CHANGE Trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, E.; Duan, L.; Cohen, H.; Kiger, H.; Pancake, L.; Brekke, J. Integrating Behavioral Healthcare for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Peer Health Navigator Intervention. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 182, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, E.; Fulginiti, A.; Pahwa, R.; Tallen, L.; Duan, L.; Brekke, J.S. A Pilot Test of a Peer Navigator Intervention for Improving the Health of Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Barbaresso, M.M.; Lai, Z.; Nord, K.M.; Bramlet, M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Post, E.P.; Almirall, D.; Bauer, M.S. Improving Physical Health in Patients with Chronic Mental Disorders: Twelve-Month Results from a Randomized Controlled Collaborative Care Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Bramlet, M.; Barbaresso, M.M.; Nord, K.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Lai, Z.; Post, E.P.; Almirall, D.; Verchinina, L.; Duffy, S.A.; et al. SMI Life Goals: Description of a Randomized Trial of a Collaborative Care Model to Improve Outcomes for Persons with Serious Mental Illness. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2014, 39, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Lai, Z.; Post, E.P.; Schumacher, K.; Nord, K.M.; Bramlet, M.; Chermack, S.; Bialy, D.; Bauer, M.S. Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess Reduction of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Patients with Bipolar Disorder: The Self-Management Addressing Heart Risk Trial (SMAHRT). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e655–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Nord, K.M.; Van Poppelen, C.; Kyle, J.; Bauer, M.S.; Waxmonsky, J.A.; Lai, Z.; Kim, H.M.; Eisenberg, D.; et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Implementation Strategies to Promote Collaborative Care Attendance in Community Practices. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Post, E.P.; Nossek, A.; Drill, L.; Cooley, S.; Bauer, M.S. Improving Medical and Psychiatric Outcomes Among Individuals with Bipolar Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Post, E.P.; Nossek, A.; Sonel, E.; Drill, L.J.; Cooley, S.; Bauer, M.S. Service Delivery in Older Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Review and Development of a Medical Care Model. Bipolar Disord. 2008, 10, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Higgins, T.C.; Esposito, D.; Hamblin, A. Integrating Health Care for High-Need Medicaid Beneficiaries with Serious Mental Illness and Chronic Physical Health Conditions at Managed Care, Provider, and Consumer Levels. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2017, 40, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, M.E.; Kanuch, S.W.; Martin, S.; Kaiser, D.; Blixen, C.; Fuentes-Casiano, E.; Sajatovic, M.; Dawson, N.V. A Nursing Approach to Self-Management Education for Individuals with Mental Illness and Diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. Publ. Am. Diabetes Assoc. 2016, 29, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lewis, M.; Chondros, P.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Lee, Y.Y.; Gunn, J.M.; Harvey, C.; Furler, J.; Osborn, D.; Castle, D.; Davidson, S.; et al. The Assertive Cardiac Care Trial: A Randomised Controlled Trial of a Coproduced Assertive Cardiac Care Intervention to Reduce Absolute Cardiovascular Disease Risk in People with Severe Mental Illness in the Primary Care Setting. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 97, 106143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombe, G.; Harrold, A.; Brown, K.; Hennessy, L.; Clarke, M.; Hanlon, D.; O’Brien, S.; Lyne, J.; Corcoran, C.; McGorry, P.; et al. Key Worker-Mediated Enhancement of Physical Health in First Episode Psychosis: Protocol for a Feasibility Study in Primary Care. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meepring, S.; Chien, W.T.; Gray, R.; Bressington, D. Effects of the Thai Health Improvement Profile Intervention on the Physical Health and Health Behaviours of People with Schizophrenia: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nover, C.H. Mental Health in Primary Care: Perceptions of Augmented Care for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. Soc. Work Health Care 2013, 52, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsen, R.I.; Peacock, G.; Smith, S. Developing a Service to Monitor and Improve Physical Health in People with Serious Mental Illness. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 12, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, P.; Griswold, K.S.; Homish, G.G.; Watkins, R. Family Practice Enhancements for Patients with Severe Mental Illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2013, 49, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, S.I.; Bartels, S.J.; Mueser, K.T.; Naslund, J.A.; Wolfe, R.; Pixley, H.S.; Josephson, L. Feasibility and Effectiveness of an Automated Telehealth Intervention to Improve Illness Self-Management in People with Serious Psychiatric and Medical Disorders. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rozing, M.P.; Jønsson, A.; Køster-Rasmussen, R.; Due, T.D.; Brodersen, J.; Bissenbakker, K.H.; Siersma, V.; Mercer, S.W.; Guassora, A.D.; Kjellberg, J.; et al. The SOFIA Pilot Trial: A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Coordinated, Co-Produced Care to Reduce Mortality and Improve Quality of Life in People with Severe Mental Illness in the General Practice Setting. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Gunzler, D.D.; Kanuch, S.W.; Cassidy, K.A.; Tatsuoka, C.; McCormick, R.; Blixen, C.E.; Perzynski, A.T.; Einstadter, D.; Thomas, C.L.; et al. A 60-Week Prospective RCT of a Self-Management Intervention for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness and Diabetes Mellitus. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajatovic, M.; Dawson, N.V.; Perzynski, A.T.; Blixen, C.E.; Bialko, C.S.; McKibbin, C.L.; Bauer, M.S.; Seeholzer, E.L.; Kaiser, D.; Fuentes-Casiano, E. Best Practices: Optimizing Care for People with Serious Mental Illness and Comorbid Diabetes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.; Yeomans, D.; Bushe, C.J.P.; Eriksson, C.; Harrison, T.; Holmes, R.; Mynors-Wallis, L.; Oatway, H.; Sullivan, G. A Well-Being Programme in Severe Mental Illness. Baseline Findings in a UK Cohort. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 1971–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, S.; Yeomans, D.; Bushe, C.J.P.; Eriksson, C.; Harrison, T.; Holmes, R.; Mynors-Wallis, L.; Oatway, H.; Sullivan, G. A Well-Being Programme in Severe Mental Illness. Reducing Risk for Physical Ill-Health: A Post-Programme Service Evaluation at 2 Years. Eur. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speyer, H.; Christian Brix Nørgaard, H.; Birk, M.; Karlsen, M.; Storch Jakobsen, A.; Pedersen, K.; Hjorthøj, C.; Pisinger, C.; Gluud, C.; Mors, O.; et al. The CHANGE Trial: No Superiority of Lifestyle Coaching plus Care Coordination plus Treatment as Usual Compared to Treatment as Usual Alone in Reducing Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders and Abdominal Obesity. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Speyer, H.; Nørgaard, H.C.B.; Hjorthøj, C.; Madsen, T.A.; Drivsholm, S.; Pisinger, C.; Gluud, C.; Mors, O.; Krogh, J.; Nordentoft, M. Protocol for CHANGE: A Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing Lifestyle Coaching plus Care Coordination versus Care Coordination Alone versus Treatment as Usual to Reduce Risks of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults with Schizophrenia and Abdominal Obesity. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Voort, T.Y.G.; van Meijel, B.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Goossens, P.J.J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Kupka, R.W. Collaborative Care for Patients with Bipolar Disorder: Effects on Functioning and Quality of Life. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 179, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velligan, D.I.; Castillo, D.; Lopez, L.; Manaugh, B.; Davis, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Milam, A.C.; Dassori, A.; Miller, A.L. A Case Control Study of the Implementation of Change Model Versus Passive Dissemination of Practice Guidelines for Compliance in Monitoring for Metabolic Syndrome. Community Ment. Health J. 2013, 49, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, J.; Siddiqi, N.; Koyanagi, A.; Siskind, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Galletly, C.; Allan, S.; Caneo, C.; Carney, R.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: A Blueprint for Protecting Physical Health in People with Mental Illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 675–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Mehtälä, J.; Vattulainen, P.; Correll, C.U.; Tiihonen, J. 20-year Follow-up Study of Physical Morbidity and Mortality in Relationship to Antipsychotic Treatment in a Nationwide Cohort of 62,250 Patients with Schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, S.; Howard, L.; Thornicroft, G. ‘Diagnostic Overshadowing’: Worse Physical Health Care for People with Mental Illness. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2008, 118, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruins, J.; Jörg, F.; Bruggeman, R.; Slooff, C.; Corpeleijn, E.; Pijnenborg, M. The Effects of Lifestyle Interventions on (Long-Term) Weight Management, Cardiometabolic Risk and Depressive Symptoms in People with Psychotic Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, R.G.; Roumans, N.J.T.; Arkenbosch, L.A.J.; Mariman, E.C.M.; van Baak, M.A. The Effect of Rate of Weight Loss on Long-Term Weight Regain in Adults with Overweight and Obesity: The Effect of Rate of Weight Loss on Weight Regain. Obesity 2016, 24, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, M. Framework for Design and Evaluation of Complex Interventions to Improve Health. BMJ 2000, 321, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, M.; Davies, M.; Edwards, A. What Are the External Influences on Information Exchange and Shared Decision-Making in Healthcare Consultations: A Meta-Synthesis of the Literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M.; Wallerstein, E. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-04544-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Neumann, M.S.; Pincus, H.A.; Bauer, M.S.; Stall, R. Implementing Evidence-Based Interventions in Health Care: Application of the Replicating Effective Programs Framework. Implement. Sci. 2007, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grol, R.; Wensing, M.; Eccles, M.; Davis, D. Improving Patient Care the Implementation of Change in Health Care, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-52596-8. [Google Scholar]

- Keaney, F.; Gossop, M.; Dimech, A.; Guerrini, I.; Butterworth, M.; Al-Hassani, H.; Morinan, A. Physical Health Problems among Patients Seeking Treatment for Substance Use Disorders: A Comparison of Drug Dependent and Alcohol Dependent Patients. J. Subst. Use 2011, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, P.; Lignou, S.; Sheehan, M.; Singh, I. Measuring the Impact of Participatory Research in Psychiatry: How the Search for Epistemic Justifications Obscures Ethical Considerations. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorius, L.; Viehmann, A.; Leve, V.; Grabe, H.J.; Hewer, W.; Reif, A.; Hahn, M.; Köhne, M.; Jacobi, F.; Pollmanns, J.; et al. PSY-KOMO—Verbesserung der Behandlungsqualität bei Schwer Psychisch Kranken Menschen zur Reduktion Somatischer Komorbidität und Verhinderung Erhöhter Mortalität; Deutscher Kongress für Versorgungsforschung: Potsdam, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type/Content of the Study Intervention | Studies (Study Identification Number from Table S7, See Supplementary Materials) | Number of Studies (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery involves individual setting | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 | 37 |

| Delivery involves group setting | 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 13, 15, 17, 18, 19, 25, 26, 27, 31, 32, 36 | 17 |

| Phone maintenance | 1, 29 | 2 |

| App-based intervention | 34 | 1 |

| Peer-led intervention | 15, 17, 22, 24 | 4 |

| Peer-specialist involvement | 4, 13 | 2 |

| Care-management | 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37 | 27 |

| Self-management training | 1, 4, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 34 | 23 |

| Physical health education | 4, 5, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33 | 16 |

| Health screening and monitoring | 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 20, 21, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37 | 16 |

| Distinct training to improve health care utilization | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 13, 15, 16, 17, 23, 24, 30 | 13 |

| Care-plan development | 7, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 35, 37 | 9 |

| Motivational support | 2, 7, 12, 14, 16, 19, 30 | 7 |

| Treatment adherence support | 2, 7, 12, 15, 17, 20 | 6 |

| Problem solving training | 1, 7, 14, 22, 37 | 5 |

| Improvement of health careinformation interface | 3, 11, 33, 38 | 4 |

| Empowerment | 3 | 1 |

| Stigma-reduction | 27 | 1 |

| Structured doctor and nurse visits | 3 | 1 |

| Lifestyle changes | 1, 12, 15, 17, 19, 23, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36 | 12 |

| Mental health education | 1, 5, 6, 9, 17, 18, 25, 26, 27, 37 | 10 |

| Staff training | 3, 4, 18, 25, 26, 27, 33, 35, 38 | 9 |

| Wellness enhancement | 5, 13, 28, 31 | 4 |

| Involvement of social network | 8, 28, 37 | 3 |

| Crisis intervention | 8 | 1 |

| Critical appraisal of medication | 36 | 1 |

| Local implementation customization of intervention | 38 | 1 |

| Support in daily living | 3 | 1 |

| Outcome Measure | Studies (Study Identification Number from Table S7, See Supplementary Materials) | Number of Studies (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-report based data | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 | 35 |

| Thereof: no other data-sources than self-report based data | 10, 13, 15, 17, 24, 25, 27, 31, 37 | 9 |

| Physiological measures | 1, 7, 9, 12, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36 | 18 |

| Administrative data | 3, 8, 11, 16, 21, 28, 29, 33, 35, 38 | 10 |

| Participation data (e.g., attendance rate) | 6, 11, 22, 33, 34 | 5 |

| Behavioral assessment | 2, 4 | 2 |

| Study Authors’ Interpretation of the Intervention Success | Studies (Study Identification Number from Table S7, See Supplementary Materials) | Number of Studies (n = 33) |

|---|---|---|

| Improvement of other physical health-behavior related outcomes, besides service utilization | 1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 24, 30, 32, 34, 37 | 14 |

| Improvement in physical health outcomes | 2, 5, 9, 12, 14, 15, 18, 25, 26, 30, 32, 36, 37 | 13 |

| Improvement in health service utilization | 3, 5, 6, 9, 11, 17, 21, 24, 33, 38 | 10 |

| Improvement in mental health outcomes | 1, 2, 3, 5, 15, 16, 18, 32, 36, 37 | 10 |

| No positive physical health related outcomes at all | 10, 19, 23, 27, 28, 31 | 6 |

| Reduction of emergency department use | 5, 6, 8, 24 | 4 |

| Theoretical Rationale or Model | Studies (Study Identification Number from Table S7, See Supplementary Materials) | Number of Studies (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Based on evidence-based intervention (s) | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 30, 35, 37 | 17 |

| Adaption of a care model or framework of healthcare | 3, 5, 7, 9, 12, 18, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 33 | 13 |

| Based on established theory | 1, 2, 14, 18, 20, 21, 23 | 7 |

| Use of a study implementation framework | 10, 22, 27, 29, 35, 38 | 6 |

| No distinct model or theoretical rationale | 8, 22, 28, 31, 36 | 5 |

| Based on eclectic empirical evidence | 21, 32, 34, 38 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strunz, M.; Jiménez, N.P.; Gregorius, L.; Hewer, W.; Pollmanns, J.; Viehmann, K.; Jacobi, F. Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010126

Strunz M, Jiménez NP, Gregorius L, Hewer W, Pollmanns J, Viehmann K, Jacobi F. Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrunz, Michael, Naomi Pua’nani Jiménez, Lisa Gregorius, Walter Hewer, Johannes Pollmanns, Kerstin Viehmann, and Frank Jacobi. 2023. "Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010126

APA StyleStrunz, M., Jiménez, N. P., Gregorius, L., Hewer, W., Pollmanns, J., Viehmann, K., & Jacobi, F. (2023). Interventions to Promote the Utilization of Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010126