Health Tourism—Subject of Scientific Research: A Literature Review and Cluster Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review on Health Tourism

- post-illness and post-trauma recovery,

- the desire to remove the adverse consequences of stress,

- anti-ageing and beauty treatments (including plastic surgery),

- fighting addictions,

- the decision to improve one’s health condition by undergoing a specialized healthcare intervention or operation in a relaxed atmosphere in an environment not resembling a hospital,

- a way of accessing increasingly diverse complementary therapies related to preventive healthcare measures.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methodology

3.2. Data Collection and Research Tasks

- (1)

- date published: the study took account of papers published between 2000 and 2022;

- (2)

- publication type: the study took account of papers published in reviewed scientific journals and books;

- (3)

- publication subject: the study took account of publications focused on selected keywords.

4. Results

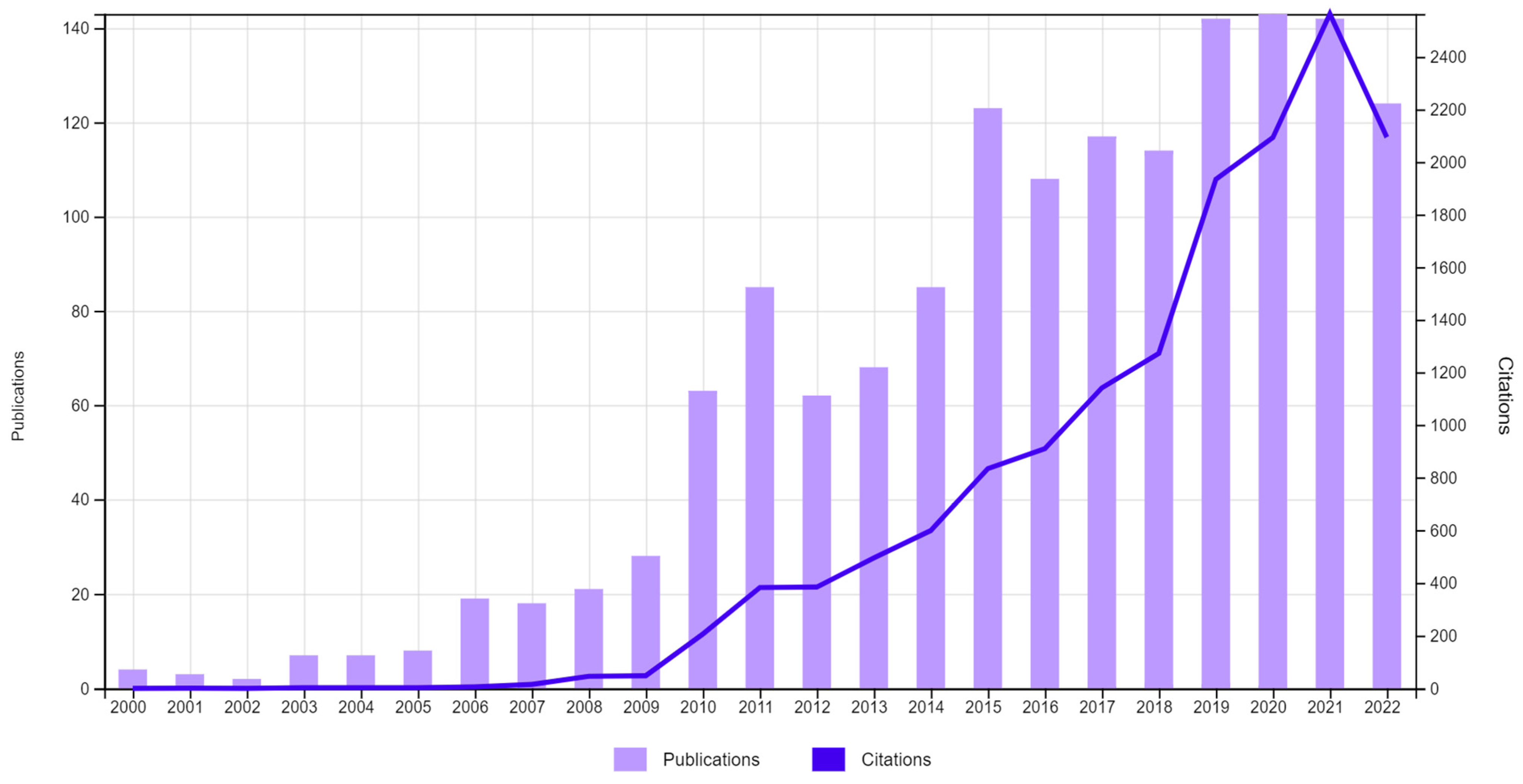

4.1. General Trend in Health Tourism Publications

4.2. Web of Science Categories

4.3. Analysis of Publication Sources

4.4. Analysis of Publications by Country and Research Center

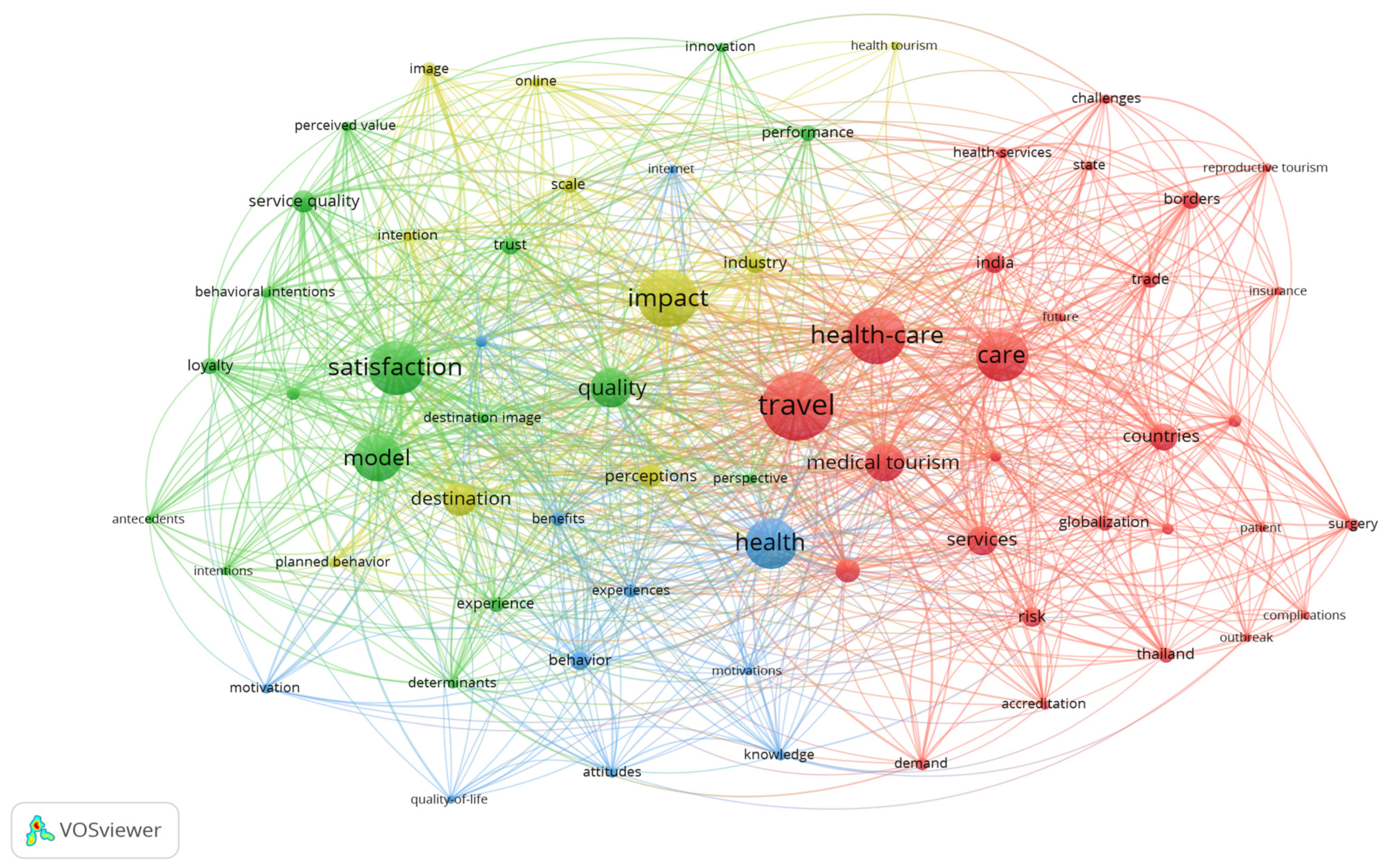

4.5. Analysis of Main Research Areas

- Retrieving database records using criteria detailed in the Methodology section.

- Exporting data, including authors’ names, title, abstract, keywords, and references.

- Mapping the relationships that underpin the thematic clusters. The analysis of frequencies was carried out for a set of keywords that occurred in no less than ten phrases.

- Analyzing the results.

5. Discussion

5.1. Cluster 1 (Green): Patient Satisfaction Built upon Trust

5.2. Cluster 2 (Yellow): Health Impacts of Holiday Destinations

5.3. Cluster 3 (Blue): Health Behaviors as an Important Part of Human Activity (Including the Economic Aspect, Which Plays a Decisive Role in Choosing a Tourism Destination)

5.4. Cluster 4 (Red): Traveling with a View to Regain One’s Health

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juul, M. Tourism and the European Union. Recent Trends and Policy Developments; European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, R.; Guia, J.; Mihalič, T.; Prats, L.; Blasco, D.; Ferrer-Roca, N.; Lawler, M.; Jarratt, D. Research for TRAN Committee—European Tourism: Recent Developments and Future Challenges; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). World Tourism Barometer 2017; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism for Development. 20 Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development; Public Disclosure Authorized. Knowledge Series; International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.; Cincera, M. Tourism demand, low cost carriers and European institutions: The case of Brussels. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 73, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista e Silva, F.; Herrera, M.A.M.; Rosina, K.; Barranco, R.R.; Freire, S.; Schiavina, M. Analysing spatiotemporal patterns of tourism in Europe at High-Resolution with conventional and big data sources. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhiliola, A.; Merita, M. Tourism an Important Sector of Economy Development. Ann. Econ. Ser. Constantin Brancusi Univ. Fac. Econ. 2009, 1, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Saveriades, A. Establishing the social tourism carrying capacity for the tourist resorts of the east coast of the Republic of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2001, 21, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, M. Uwarunkowania rozwoju turystyki międzynarodowej. In Turystyka (Tourism); Kurek, W., Ed.; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2007; pp. 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Semmerling, A. Udział turystyki zagranicznej w rozwoju gospodarczym wybranych krajów Europy wschodniej. Gospodarcze i ekonomiczne aspekty rozwoju turystyki. Tour. Recreat. Sci. J. 2017, 19, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Roman, M.; Grzegorzewska, E.; Pietrzak, P.; Roman, K. Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourism in European Countries: Cluster Analysis Findings. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, L.; Cavallo, A.; Romagnoli, L. Diversified Farms Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic: First Signals from Italian Case Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S. Medical Tourism in India. India—A New Hub of Medical Tourism; Booksclinic Publishing: Bilaspur, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bończak, B. Aktywne formy turystyki–problemy terminologiczne (Active forms of tourism: The terminological problems). Tour. Geogr. Workshop 2013, 3, 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Różycki, P. Zarys wiedzy o turystyce (An Outline of What We Know about Tourism); Proksenia Publishing House: Krakow, Poland, 2006; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Health and medical tourism: A kill or cure for global public health? Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cui, F.; Balezentis, T.; Streimikiene, D.; Jin, H. What drives international tourism development in the Belt and Road Initiative? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfagharian, M.; Rajamma, R.K.; Naderi, I.; Torkzadeh, S. Determinants of medical tourism destination selection process. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Spa and Health Tourism. In Sport and Adventure Tourism; Hudson, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Schmerler, K. Medical Tourism in Germany, Determinants of International Patients’ Destination Choice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Azara, I.; Michopoulou, E.; Niccolini, F.; Taff, B.D.; Clarke, A. Tourism, Health, Wellbeing and Protected Areas; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bagga, T.; Vishnoi, S.K.; Jain, S.; Sharma, R. Medical Tourism: Treatment, Therapy & Tourism. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 4447–4453. [Google Scholar]

- Boruszczak, M. (Ed.) Turystyka zdrowotna; Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management in Gdansk: Gdansk, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerling, T.; Kickbusch, I.; Told, M. The European Union as a Global Health Actor; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Puczko, L. Health, Tourism and Hospitality: Spas, Wellness and Medical Travel; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Białk-Wolf, A.; Arent, M.; Buziewicz, A. Analiza Podaży Turystyki Zdrowotnej w Polsce; Polish Tourism Organization: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Erfurt-Cooper, P.; Cooper, M. Health and Wellness Tourism: Spas and Hot Springs; Channel View Publications Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harasim, B. Turystyka Zdrowotna Jako Czynnik Rozwoju Gospodarki; Faculty of Economics and Management, University of Białystok: Białystok, Poland, 2014; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, J. Turystyka Zdrowotna a Uzdrowiska Europejskich Krajów Socjalistycznych; Polish Society of Balneology, Physical Medicine and Biological and Climate Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, J.N. Socialist Cuba: A Study of Health Tourism. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi, M. Sustaining tourism by managing health and sanitation conditions. In Proceedings of the XVII Inter-American Travel Congress, San José, Costa Rica, 10 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gaworecki, W.W. Turystyka (Tourism); PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 2003; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.; King, B.; Milner, L. The health resort sector in Australia: A positioning study. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A. Turystyka uzdrowiskowa (Spa Tourism); Study Materials; Scientific Publishing House of the University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Białk-Wolf, A. Zdrowotna funkcja współczesnej. In Turystyka zdrowotna (Health Tourism); Boruszczak, M., Ed.; Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management in Gdansk: Gdansk, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Łoś, A. Turystyka zdrowotna—Jej formy i motywy: Czynniki rozwoju turystyki medycznej w Polsce. Econ. Probl. Relat. Serv. 2012, 84, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.H. (Ed.) Medical Tourism: The Ethics, Regulation, and Marketing of Health Mobility; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, J.; Demicco, F.J. Medical Tourism and Wellness: Hospitality Bridging Healthcare (H2H); Apple Academic Press Inc.: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, H. Medical Tourism Is the New Wave of Outsourcing from INDIA. India Daily, 23 December 2006. Available online: http://www.indiadaily.com/editorial/14858.asp (accessed on 20 September 2007).

- Malhotra, N.; Dave, K. An Assessment of Competitiveness of Medical Tourism Industry in India: A Case of Delhi NCR. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Compet. 2022, 17, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.C.; Van De Weerdt, M. The health care tourism product in Western Europe. Tour. Rev. 1991, 46, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.S.; Merkebu, J.; Varpio, L. State-of-the-art literature review methodology: A six-step approach for knowledge synthesis. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2022, 11, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Klincewicz, K. Bibliometria a inne techniki analityczne. In Bibliometria w zarządzaniu technologiami i badaniami naukowymi (Use of Bibliometrics in Managing Technologies and Scientific Research); Klincewicz, K., Żemigała, K., Mijal, M., Eds.; Ministry of Science and Higher Education: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Badger, D.; Nursten, J.; Williams, P.; Woodward, M. Should all literature reviews be systematic? Eval Res Educ. 2000, 14, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Takigawa, I.; Zeng, J.; Mamitsuka, H. Field independent probabilistic model for clustering multi-field documents. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, 45, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VoSviewer. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Aveyard, H. Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care: A Practical Guide; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, X.Y.; Sun, J.; Bai, B. Bibliometrics of social media research: A co-citation and co-word analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emich, K.J.; Kumar, S.; Lu, L.; Norder, K.; Pandey, N. Mapping 50 years of small group research through small group research. Small Group Res. 2020, 51, 659–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadad Hosseini, S.H.; Behboudi, L. Brand trust and image: Effects on customer satisfaction. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2017, 30, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tse, E.C.-Y.; He, Z. Influence of Customer Satisfaction, Trust, and Brand Awareness in Health-related Corporate Social Responsibility Aspects of Customers Revisit Intention: A Comparison between US and China. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunets, A.N.; Yankovskaya, V.; Plisova, A.B.; Mikhailova, M.V.; Vakhrushev, I.V.; Aleshko, R.A. Health tourism in low mountains: A case study. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, P.M.; Bridges, J.F.P. Globalization and healthcare: Understanding health and medical tourism. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Research. 2006, 6, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E.; Alvelos, H. The economic impact of health tourism programmes. In Quantitative Methods in Tourism Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. The economic effects of medical tourism industry on Kwangwon province. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2011, 15, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, H. Tourism in Kenya’s national parks: A cost-benefit analysis. Stud. Undergrad. Res. Guelph 2012, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pruñonosa, J.; Raya, J.M.; CrespoSogas, P.; Mur-Gimeno, E. The economic and social value of spa tourism: The case of balneotherapy in Maresme. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karuppan, C.M.; Karuppan, M. Changing trends in health care tourism. Health Care Manag 2010, 29, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiry, M.; Vequist, D.G. Traveling abroad for medical care: U.S. medical tourists’ expectations and perceptions of service quality. Health Mark. Q. 2011, 28, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freyer, W.; Kim, B.S. Medizintourismus und Medizinreisen—Eine inter-disziplinäre Betrachtung (Medical tourism and travel—An interdisciplinary approach). Gesundheitswesen 2014, 76, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Nature-based tourism as therapeutic landscape in a COVID era: Autoethnographic learnings from a visitor’s experience in Iceland. GeoJournal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.; Jęczmyk, A.; Zawadka, J.; Uglis, J. Agritourism in the Era of the Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Rapid Assessment from Poland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Shenjing, H. The co-evolution of therapeutic landscape and health tourism in bama longevity villages, China: An actor-network perspective. Health Place 2020, 66, 102448. [Google Scholar]

- Manthiou, A.; Kuppelwieser, V.G.; Klaus, P. Reevaluating tourism experience measurements: An alternative Bayesian approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P. Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist Experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Bilgihan, A. Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 19, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.L.; Lee, Y.J.; Huang, P.H. Creative experiences, memorability and revisit intention in creative tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 19, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Molina, M.Á.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Castañeda-García, J.A. The moderating role of past experience in the formation of a tourist destination’s image and in tourists’ behavioural intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafford, B. The Third Wave—Medical Tourism in the 21st Century. South. Med. J. 2009, 102, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, S.; Guo, L.; Edvardsson, B. Role of Resource Integration in Adoption of Medical Tourism Service. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2013, 5, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobo, E.; Herlihy, E.; Bicker, M. Selling Medical Travel to US Patient-Consumers: The Cultural Appeal of Website Marketing Messages. Anthropol. Med. 2011, 18, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I.; Schanzel, H.; Smith, K. How Ageing Populations Lead to the Incremental Decline of New Zealand Tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, H. Affective Journeys: The Emotional Structuring of Medical Tourism in India. Anthropol. Med. 2011, 18, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The Healthcare Hotel: Distinctive Attributes for International Medical Travelers. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.; Kucukusta, D.; Song, H. Medical Tourism Development in Hong Kong: An Assessment of the Barriers. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.; Honegger, F.; Hubeli, J. Health tourism: Definition focused on the Swiss market and conceptualisation of health(i)ness. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2012, 26, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, L.; Labonte, R.; Runnels, V.; Packer, C. Medical Tourism Today: What is the State of Existing Knowledge? J. Public Health Policy 2010, 31, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alejziak, W. Aktywność turystyczna: Międzynarodowe i krajowe zróżnicowanie oraz kwestia wykluczenia społecznego. Tourism 2011, 21, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgione, D.A.; Smith, P.C. Medical tourism and its impact on the US health care system. J. Health Care Finance 2007, 34, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gurhan-Canli, Z.; Priester, J.R. The Social Psychology of Consumer Behavior; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, R.; Woodside, G. Tourism Behavior: Travellers’ Decisions and Actions; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, S.; Xiang, R.L. Domestic Medical Tourism: A Neglected Dimension of Medical Tourism Research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, H.; Fyall, A.; Willis, C.; Page, S.; Ladkin, A.; Hemingway, A. Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1830–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkert, A.; Singh, N. An Investigation of American Medical Tourists’ Posttravel Experience. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediansyah Mts, A.; Hamsal, M.; Bramantoro Abdinagoro, S. A decade of medical tourism research: Looking back to moving forward. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. Medical travel of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases inpatients in central China. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 127, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morito, C. Motives for Travel in Domestic Medical Tourism. Jpn. Mark. J. 2020, 39, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoijam, S.L.S.; Khan, T. Prospects and Challenges of Medical Tourism. In Global Developments in Healthcare and Medical Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.A.; Barber, D.S. Ethical and sustainable healthcare tourism development: A primer. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 15, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, L. Medical tourism: Concerns, benefits, and the American perspective. J. Leg. Med. 2007, 28, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, M.-Y.; Wei, W.; Morrison, A.M.; Kelly, C. The effect of destination source credibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: An application of stimulus-organism-response theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denley, T.J.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Boley, B.B.; Hehir, C.; Abrams, J. Individuals’ intentions to engage in last chance tourism: Applying the value-belief-norm model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1860–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X.; Corrons, A. Sustainability-oriented innovation in tourism: An analysis based on the decomposed theory of planned behavior. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Hansen, E.N.; Kangas, J.; Laukkanen, T. How national culture and ethics matter in consumers’ green consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Budke, C. Tourism in a world with pandemics: Local–global responsibility and action. J. Tour. Futur. 2020, 6, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, C.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Less sitting, more physical activity, or higher fitness? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S.F.; Schamel, G. Sustainable tourism development: A dynamic model incorporating resident spillovers. Tour. Econ. 2020, 27, 1561–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlemmer, P.; Barth, M.; Schnitzer, M. Research note sport tourism versus event tourism: Considerations on a necessary distinction and integration. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2020, 21, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Hahn, S.; Lee, T.; Jun, M. Two factor model of consumer satisfaction: International tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, I.L. Improving global health—Is tourism’s role in poverty elimination perpetuating poverty, powerlessness and ‘ill-being’? Glob. Public Health 2017, 12, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila, N.A.; Brea, J.A.F.; de Araújo, A.F. Health and sport. Economic and social impact of active tourism. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzić, A.; Demirović, D.; Petrevska, B.; Limbert, W. Active sport tourism in Europe: Applying market segmentation model based on human values. J. Hosp. Tour. Res 2020, 20, 1214–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, J.J. Tourism research 2.0. Ann. Tour. Res 2012, 39, 883–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachniewska, M. Health Tourism as the Determinant for New Business Models. Entrep. Manag. 2019, 20, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A. Tourism Studies and the Social Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Pierre, C.; Herskovic, V.; Sepúlveda, M. Multidisciplinary collaboration in primary care: A systematic review. Fam. Pract. 2018, 35, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, F.S. The challenges of multidisciplinary education in computer science. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2011, 26, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbellay, F.; Stock, M. Tourism as complex interdisciplinary research object. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, N.; Carrera, P. Medical tourism: Assessing the evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas 2020, 66, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.-J.; Chen, W.-C. Chinese medical tourists—Their perceptions of Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Travel motivation, benefits and constraints to destinations. In Destination Marketing and Management: Theories and Applications; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Buda, D.; d’Hautessere, A.M.; Johnstone, L. Feelings and Tourism Studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P. What is health and medical tourism? In Reimagining Sociology; Wyn, J., Warr, D., Chang, J., Lewis, J., Nolan, D., Pyett, P., Eds.; The Australian Sociological Association (TASA): Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2008; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.Y.; Ko, T.G. A cross-cultural study of perceptions of medical tourism among Chinese, Japanese and Korean tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkova, E.; Holzner, J. Motivation of Tourism Participants. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awodzl, W.; Pando, D. Medical tourism: Globalization and the marketing of medical services. Consort. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 11, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) | Year Published | Journal/Publisher | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wolski [30] | 1970 | Polish Society of Balneology, Physical Medicine and Biological and Climate Sciences | “An informed and voluntary travel away from one’s place of residence in his/her free time with a view to recover his/her body through physical and mental activities” |

| Goodrich [31] | 1993 | Journal of Travel Research | “Health tourism is defined as purposeful actions taken by tourism facilities (e.g., hotels) or destinations (e.g., Baden in Switzerland, Bath in England) to attract tourists by promoting healthcare services and facilities in addition to usual tourism amenities” |

| Tabacchi [32] | 1997 | Inter-American Travel Congress | “Any kind of travel which makes the traveler or his/her family feel healthier” |

| Gaworecki [33] | 2003 | Polish Economic Publishers | “An informed and voluntary travel away from one’s place of residence in his/her free time with a view to recover his/her body through physical and mental activities” |

| Bennet, King, Milner [34] | 2004 | Journal of Vacation Marketing | “Any kind of pleasure tourism which includes a stress-alleviating experience” |

| Lewandowska [35] | 2007 | Scientific Publishing House of the University of Szczecin | “Services which address health and leisure-related needs, improve people’s health and make them feel better” |

| Białk-Wolf [36] | 2010 | Publishing House of the Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management in Gdansk | “All relationships and developments deriving from stays and travels of people whose main motivation and goal is to improve or maintain their health status or heal their diseases” |

| Łoś [37] | 2012 | “Economic problems related to services,” Scientific Journals of the University of Szczecin | Health tourism can be divided as follows: (a) spa tourism offered in spa destinations, related to providing spa treatment services, including chronic disease management, recovery, disease prevention, and health education and promotion; (b) spa and wellness: the main goal is to offer relaxation and body care services (massage, gymnastics, cryotherapy) and ensure wellbeing (fighting stress, detoxification, oxygen therapy); (c) medical tourism offered in traditional medical centers (hospitals, clinics) in order to provide healthcare services in broad terms. |

| Field of Research | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Social Sciences | 32.7 | 488 |

| Business Economics | 16.3 | 243 |

| Public Environmental Occupational Health | 11.6 | 174 |

| Health Care Sciences Services | 9.7 | 145 |

| Environmental Sciences Ecology | 7.9 | 119 |

| General Internal Medicine | 6.3 | 95 |

| Science Technology | 3.8 | 57 |

| Surgery | 3.6 | 54 |

| Computer Science | 3.4 | 51 |

| Geography | 2.8 | 43 |

| Web of Science Categories | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitality Leisure Sport Tourism | 27.5 | 411 |

| Public Environmental Occupational Health | 11.6 | 174 |

| Health Policy Services | 7.9 | 119 |

| Management | 7.6 | 114 |

| Economics | 7.0 | 105 |

| Medicine General Internal | 6.3 | 95 |

| Business | 6.2 | 93 |

| Environmental Sciences | 5.1 | 77 |

| Environmental Studies | 4.7 | 70 |

| Health Care Sciences Services | 3.7 | 55 |

| Publication Titles | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 1.8 | 27 |

| Tourism Management | 1.7 | 26 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 1.6 | 24 |

| Iranian Journal of Public Health | 1.4 | 22 |

| International Journal of Healthcare Management | 1.4 | 21 |

| Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing | 1.1 | 17 |

| Tourism Review | 1.0 | 15 |

| Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research | 0.8 | 13 |

| Current Issues in Tourism | 0.8 | 12 |

| Journal of Travel Medicine | 0.7 | 11 |

| Publishers | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Taylor & Francis | 11.8 | 176 |

| Elsevier | 9.6 | 144 |

| Springer Nature | 9.4 | 140 |

| Emerald Group Publishing | 5.3 | 79 |

| Wiley | 4.9 | 74 |

| MDPI | 3.8 | 57 |

| Sage | 2.5 | 37 |

| Oxford Univ Press | 2.2 | 33 |

| Lippincott Williams & Wilkins | 1.8 | 28 |

| Iranian Scientific Society Medical Entomology | 1.5 | 22 |

| Author | Number of Health Tourism Publications | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Snyder, J. | 43 | 1 |

| Crooks, V.A. | 42 | 2 |

| Johnston, R. | 27 | 3 |

| Connell, J. | 18 | 4 |

| Pacheco, M.A.D. | 14 | 5 |

| Turner, L. | 13 | 6 |

| Adams, K. | 11 | 7 |

| Han, H. | 10 | 8 |

| Ormond, M. | 10 | 8 |

| Rai, A. | 10 | 8 |

| Countries | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 16.7 | 249 |

| China | 8.8 | 132 |

| Malaysia | 6.0 | 91 |

| United Kingdom | 5.5 | 82 |

| Canada | 5.4 | 81 |

| Australia | 5.2 | 78 |

| India | 4.5 | 67 |

| South Korea | 4.3 | 65 |

| Spain | 4.0 | 60 |

| Iran | 3.5 | 53 |

| Affiliations | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Simon Fraser University | 3.3 | 49 |

| State University System of Florida | 1.4 | 21 |

| Ministry of Education Science of Ukraine | 1.3 | 20 |

| University of London | 1.2 | 19 |

| University of Sydney | 1.2 | 19 |

| University of Minnesota System | 1.1 | 17 |

| University of Minnesota Twin Cities | 1.1 | 17 |

| Islamic Azad University | 1.0 | 16 |

| Universidad Del Norte | 1.0 | 15 |

| Universiti Teknologi Mara | 1.0 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roman, M.; Roman, M.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M. Health Tourism—Subject of Scientific Research: A Literature Review and Cluster Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010480

Roman M, Roman M, Wojcieszak-Zbierska M. Health Tourism—Subject of Scientific Research: A Literature Review and Cluster Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010480

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoman, Michał, Monika Roman, and Monika Wojcieszak-Zbierska. 2023. "Health Tourism—Subject of Scientific Research: A Literature Review and Cluster Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010480

APA StyleRoman, M., Roman, M., & Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M. (2023). Health Tourism—Subject of Scientific Research: A Literature Review and Cluster Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010480