Health Experiences of African American Mothers, Wellness in the Postpartum Period and Beyond (HEAL): A Qualitative Study Applying a Critical Race Feminist Theoretical Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1. What are the drivers of postpartum primary care utilization for Black women, considering cultural, social, and historical contexts about health, healthcare, wellness, and identity?

- RQ2. What are the needs, barriers, and facilitators of postpartum primary care for Black women?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1.1. Critical Race Feminism

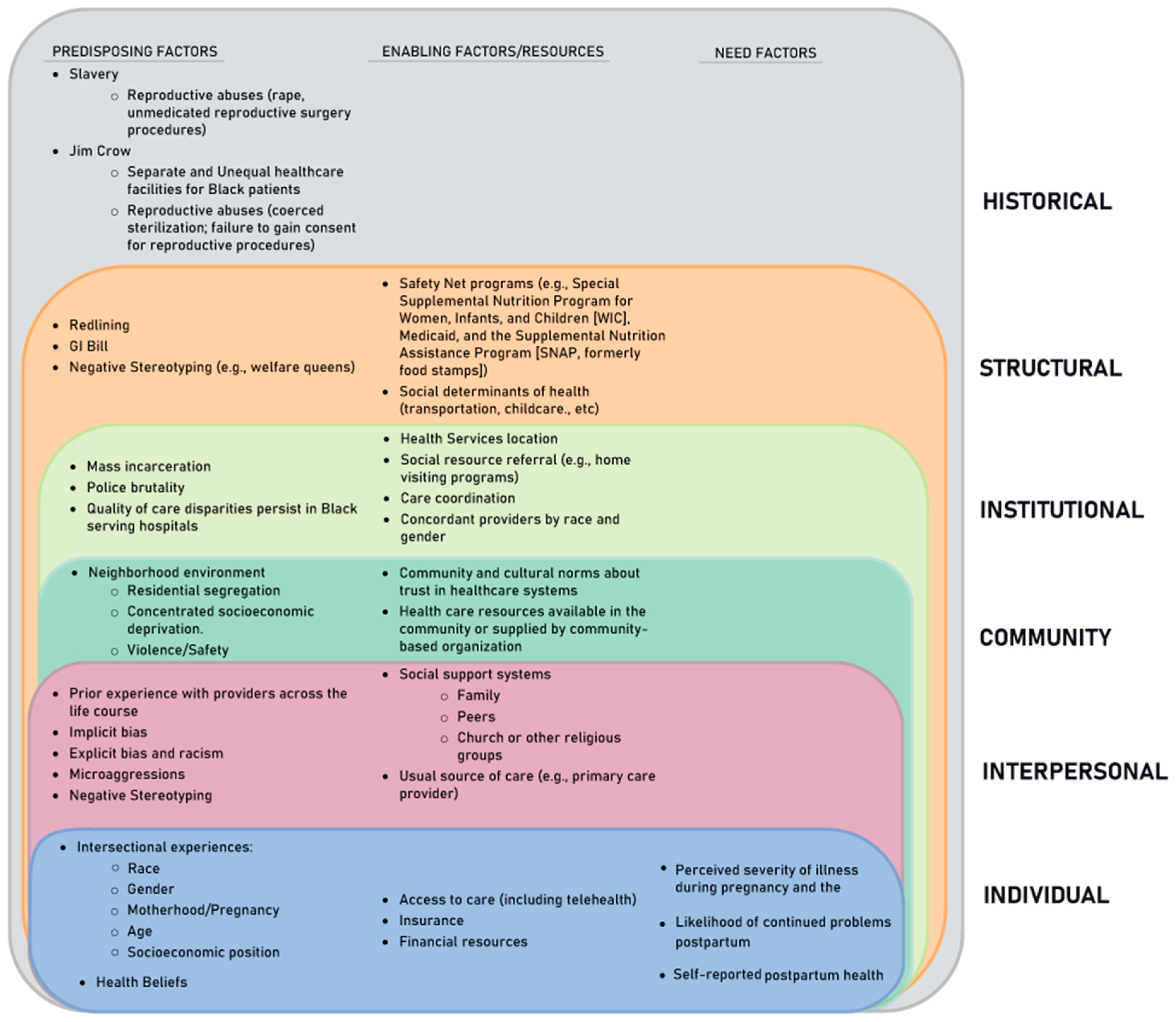

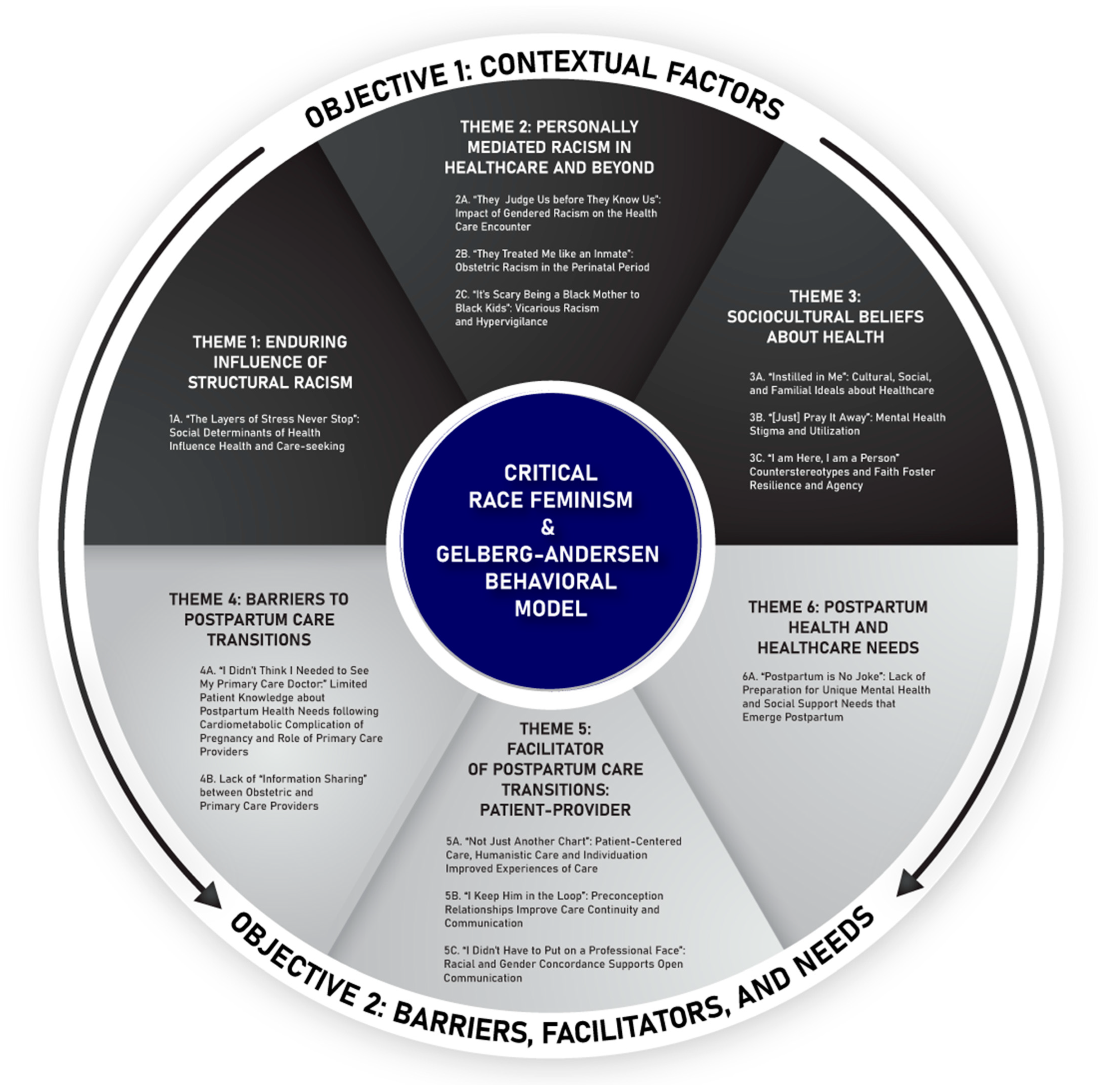

2.1.2. Gelberg–Andersen Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2.2. Study Design

2.2.3. Study Setting

2.2.4. Contemporary Context and Race Relations

2.2.5. Participant Sampling

2.2.6. Instrumentation

2.2.7. Interviews

2.2.8. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Enduring Influence of Structural Racism

(1A) “The Layers of Stress Never Stop”: Social Determinants of Health Influence Health and Care-Seeking

“…I think about the trip… [like] ‘Dang, I got to catch this many buses, or I have to pay this much to get there?’ I’m just not going to go. So transportation is one of the biggest things for me for why I don’t go to [healthcare] appointments”-P9.

“I can’t do hair as often as I was [before the pandemic] because you can’t be around as many people…so it messed up my money… and because my daughter’s doing virtual learning I got to help her with that. I also have another son…I can’t depend on anybody else for that…there’s a lot that I have to do on my own”-P8.

“It’s like the layers of stress never stop and then being stressed really can bring the lupus out. I can’t afford to have a lupus attack because I have no one to take care of my kids… And so that makes a difference in my health too because I don’t really have the time to take care of myself because I have so much to worry about as it it”-P6.

3.2. Theme 2: Personally Mediated Racism in Healthcare and Beyond

3.2.1. (2A) “They Judge Us before They Know Us”: Impact of Gendered Racism on the Health Care Encounter

3.2.2. (2B) “They Treated Me like an Inmate”: Obstetric Racism in the Perinatal Period

“All Black women should just have their babies at home instead of the hospital because something bad is going to happen [here]”-P19.

3.2.3. (2C) “It’s Scary Being a Black Mother to Black Kids”: Vicarious Racism and Hypervigilance

“That’s something that always sat in the back of my head, keeping [my son] safe, especially living somewhere like Baltimore”-P16.

“… I mean, [racism] happens so often and you do get to the point where you don’t feel it, it doesn’t affect you. You’re numb towards it because it just happens so often.”-P18

3.3. Theme 3: Sociocultural Beliefs about Health and Healthcare

3.3.1. (3A) “Instilled in Me”: Cultural, Social, and Familial Ideals about Seeking Preventative Healthcare

“Mom was [a] very, go to the doctors [type] … we always went to the eye doctor, dentist, primary care, that’s something that was big in our house.”-P4

“…When my mother would complain about a knot on her hand [they later found out was cancer], no one would do anything about it, …and when I was a child with a breathing problem they did not take seriously. [The doctors] would say I didn’t have a breathing problem. I think it had something to do with me being Black, and I think it had something to do with my mother being Black”-P4.

3.3.2. (3B) “[Just] Pray It away”: Mental Health Stigma and Utilization

3.3.3. (3C) “I Am Here, I Am a Person” Counterstereotypes and Faith Foster Resilience and Agency

3.4. Theme 4: Barriers to Postpartum Care Transitions

3.4.1. (4A) “I Didn’t Think I Needed to See My Primary Care Doctor:” Limited Patient Knowledge about Postpartum Health Needs Following Cardiometabolic Complication of Pregnancy and Role of Primary Care Providers

3.4.2. (4B) Lack of “Information Sharing” between Obstetric and Primary Care Providers

3.5. Theme 5: Facilitators of Postpartum Care Transitions: Patient-Provider Relationships

3.5.1. (5A) “Not just Another Chart”: Patient-Centered Care, Humanistic Care and Individuation Improved Experiences of Care

“I like it when someone is attentive, and they’re able to talk to me like I’m a human, and not just like, ‘You’re just a number.’ My primary care provider would answer all of my questions, make sure everything was understood before I left [in contrast], I had a provider [during pregnancy], and I did not like her because she didn’t really take the time out to explain stuff or really got to know me or tell me what I should be expecting out of this…”-P11

3.5.2. (5B) “I Keep Him in the Loop”: Preconception Relationships Improve Care Continuity and Communication

“I’ve been a patient of hers for, I’d probably say, maybe 8 or 10 years. I did discuss [plans to get pregnant] with her last time I saw her; I’d asked her when I got on the blood pressure medicine, was it safe to be on this specific medicine while I was pregnant and for breastfeeding.”-P16

3.5.3. (5C) “I Didn’t Have to Put on a Professional Face”: Racial and Gender Concordance Supports Open Communication

3.6. Theme 6: Postpartum Health and Healthcare Needs

(6A) “Postpartum Is No Joke”: Lack of Preparation for Unique Mental Health and Social Support Needs That Emerge Postpartum

“Even with young mothers, young Black mothers…I think if they had more groups where they could all sit around and realize that they’re not the only one that’s scared and stuff like that and exchange number.”-P4.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.1.1. Contextual Factors and Structural Solutions

| Theme | Subtheme | Opportunities for Intervention at the following Levels: Provider (P), Community (C), System (S) + |

|---|---|---|

| Enduring Influence of Structural Racism | “The Layers of Stress Never Stop”: Social Determinants of Health Influence Health and Care-Seeking. |

|

| Personally Mediated Racism in Healthcare and Beyond | “They Judge Us before They Know Us”: Impact of Gendered Racism on the Health Care Encounter. |

|

| “They Treated Me like an Inmate”: Obstetric Racism in the Perinatal Period. “It’s Scary Being a Black Mother to Black Kids”: Vicarious Racism and Hypervigilance. |

| |

| Sociocultural Beliefs About Health and Healthcare | “Instilled in Me”: Cultural, Social, and Familial Ideals about Healthcare. |

|

| “[Just] Pray It Away”: Mental Health Stigma and Utilization. |

| |

| “I am Here, I am a Person”: Counterstereotypes and Faith Foster Resilience and Agency. |

|

4.1.2. Postpartum Primary CARE Utilization

4.1.3. Advancement of Theory and Praxis

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Introduction

Appendix A.2. COVID-19

- How did the pandemic affect your pregnancy? [Prompts: Prenatal Care]Nurse–anxiety

- How did the pandemic impact your birth plans? [Prompts: Delivery setting, Social support (i.e., family members allowed to visit, other support person like doulas)

- How is the pandemic affecting your postpartum experience? [Clinic visits, Virtual visits, Lactation support, Other health services]

- What lifestyle changes have you had to make as a result of the pandemic?

- How have you been impacted by social distancing rules and other COVID-19 prevention measures? [Prompts if needed: Work, Mask wearing]

- Has anyone in your household tested positive for COVID-19? (If no, move to #3)

- When and how did you find out?

- Did the person go to the hospital for treatment? (If no, move to d)

- What was their experience with health providers?

- What challenges did they experience in receiving appropriate care during this period?

- What role did you play in caring for this person?

- What measures are you taking to prevent COVID-19 exposure in your household?

- 8.

- Where do you usually get information about COVID-19?

- 9.

- What kinds of resources have you had access to and how could these resources be improved to meet your needs during the pandemic?

- 10.

- Are there any problems you are currently facing or problems that have gotten worse because of the COVID-19 pandemic?

- 11.

- What health issues do you have concerns about as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

- 12.

- How does this affect your health and overall wellbeing as a Black woman?

- 13.

- Have you or someone in your family/household experienced any form of prejudice or racial discrimination during this period?

- 14.

- What has been the greatest source of support and hope for you during this pandemic?

Appendix A.3. Growing-up

- How did you first learn about the idea of health and being healthy? [Prompts: what did it mean to you]

- How was your family’s feelings about health providers and the health care system shaped by your identity as a Black family?

- How would you describe your family’s ideas on health checkups (preventive health) while you were growing up?

- How often did you see a doctor while you were growing up? (if N/A go to 5)

- Why did you start seeing the doctor while growing up?

- Could you tell me about a memorable experience at a doctor’s visit?

- What went well?

- What didn’t go so well?

- If you could go back in time, what would you change about this visit?

- What challenges did you experience as a Black person while trying to get healthcare as a young adult (middle school/highschool) this period? [Prompts: Racism, Discrimination, Income level, Disease, Health Insurance, Transportation, Environment, Safety concerns]

- What did you find easy about seeking health care during this time?

Appendix A.4. Pre-Pregnancy

- How has your ideas of health and being healthy changed since growing up?

- Were you seeing a regular/general doctor/provider (primary care provider (PCP)) before your most recent pregnancy? (If no, move to 10)

- How long have you known this doctor and how did you select him/her as your PCP?

- How often do you see your PCP and what for?

- How does being a Black woman affect your relationship with your PCP?

- Could you describe your relationship with your PCP?

- During your visits, how comfortable are you with expressing your concerns and communicating your needs with this doctor?

- How would you describe the level of respect between you and your PCP?

- How would you describe the level of trust between you and your PCP?

- How do you feel about the types of information your PCP shares with you?

- How involved are you in the decision making about your care/treatment plans?

- Have you ever considered changing your PCP? Why/Why not?

- Have you ever experienced any form of judgment during a visit with your PCP?

- Have you ever felt any form of discrimination from my PCP because you are Black?

- Did you discuss your pregnancy plans with your PCP before getting pregnant? Why/Why not?

- What did you find easy about seeking health care from your PCP?

- What were some challenges you had when trying to get health care from your PCP? [Prompts: Discrimination, Income level, Health Insurance, Transportation, Environmental safety, Pre-existing conditions]

- Why were you not seeing a PCP before your most recent pregnancy?

Appendix A.5. Pregnancy

- Could you describe the relationship between your PCP and Ob/Gyn/midwife?

- Did your PCP refer you to your Ob/Gyn?

- Do your PCP and Ob/Gyn communicate about your health at any point in time?

- Could you tell me about the care you received during your most recent pregnancy.

- How is care during pregnancy different than care at other times or for other conditions? [Prompts: providers, services frequency]

- Did you see an Ob/gyn during your most recent pregnancy?

- How long have you known this doctor?

- How did you select him/her as your Ob/Gyn?

- How often did you see your Ob/Gyn and what health services do you usually seek from him/her?

- What were some challenges you experienced with seeking health care from your Ob/Gyn?

- What did you find easy about seeking health care from your Ob/Gyn?

- How does being a Black woman affect your relationship with your Ob/Gyn (midwife etc.?)

- Could you describe your relationship with your Ob/Gyn/midwife?

- During your visits, how comfortable are you with expressing your concerns and communicating your needs with this doctor?

- You probably spent a lot of time talking about the baby’s health, but what did you understand about how this pregnancy could affect your own health?

- How would you describe the level of respect between you and your Ob/Gyn?

- How would you describe the level of trust between you and your Ob/Gyn?

- How do you feel about the types of information your Ob/Gyn shares with you?

- How involved are you in the decision making about your care/treatment plans?

- Have you ever experienced any form of judgment or discrimination during any of these visits?

- Have you ever considered changing your Ob/Gyn or getting a second opinion? Why/Why not?

- Did you discuss your pregnancy plans with your Ob/Gyn before getting pregnant? Why/Why not?

- Did you experience any illness or complications during your pregnancy? [Probe: Tell me more]

- What were some challenges you experienced with seeking health care from your Ob/Gyn?

- What did you find easy about seeking health care from your Ob/Gyn?

- How did your experience with your Ob/Gyn or nurse midwife affect your likelihood of seeing other doctors or nurses after pregnancy?

Appendix A.6. Postpartum

- Could you tell me what comes to your mind when you hear the term postpartum care?

- 2.

- Could you tell me why you chose to participate in this visiting program?

- 3.

- What do you like about it?

- 4.

- Is there anything you don’t like about it?

- 5.

- Would you tell a friend to participate in this program? Why or Why not?

- 6.

- Why do you think a new mother might refuse to participate in this program?

- 7.

- If you could make changes to this program to better meet your needs, what changes would you make?

- 8.

- Traditionally home visiting has been more about supporting the baby—are there any ways that home visiting could help you more?

- What additional services could they provide?

- What other connections could they help to make for you?

- 9.

- Have you seen a PCP since the end of your most recent pregnancy (If no, continue to 15)

- 10.

- What prompted you to do so?

- 11.

- How often do you see your PCP?

- 12.

- What services do you seek from your PCP?

- 13.

- What were some challenges you experienced with seeking health care from your PCP?

- 14.

- What did you find easy about seeking health care from your PCP?

- 15.

- Why have you not seen a PCP since the end of your most recent pregnancy?

- 16.

- If you chose to seek postpartum primary care now, what factors might prevent you from doing so?

- 17.

- Have you seen other health providers apart from your Ob/Gyn since the end of your most recent pregnancy?

- 18.

- What types of health providers have you seen and what prompted you to do so?

- 19.

- How often do you see these health providers?

- 20.

- What services do you seek from these health providers?

- 21.

- What were some challenges you experienced with seeking care from these health providers?

- 22.

- What did you find easy about seeking health care from these health providers?

- What are some health goals you hope to achieve for yourself during this postpartum period?

- What kind of governments programs do you think could be created or improved to support postpartum health care for Black women like you? [Prompts: How could these help you achieve your health goals?]

- How can hospitals and clinics contribute to improve postpartum care for Black women like you? [Prompts: How could these help you achieve your health goals?]

- What can health providers do to improve the quality of postpartum care for Black women like you? [Prompts: How could these help you achieve your health goals?]

- If you could build the perfect postpartum visit with PCP—what would that look like for you?PROMPTS

- Where is it? At home, at church, at the mall, a beauty shop, a community center, or someplace else?

- By yourself, or with someone else, or with a group of women like you?

- Does it matter who is the doctor is-man, woman, Black, White, Hispanic, Asian, American-born, foreign-born, primary care or specialist?

- Who is there with you?

- How long is it?

- What do you want to talk about

- Are there any community programs you think could be created or improved to make postpartum care better for Black women in your community? [Prompts: How could these help you achieve your health goals?]

- How can your family, relatives or friends support you in achieving your health goals during this postpartum period?

- How can you contribute to improving your own health outcomes during this postpartum period?

- Are you taking these actions right now?

- What are some barriers to taking such actions?

- What would make it easier to take such actions?

References

- Division of Reproductive Health, N.C. for C.D.P. and H.P. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Creanga, A.A.; Bateman, B.T.; Kuklina, E.V.; Callaghan, W.M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity: A Multistate Analysis, 2008–2010. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 435.e1–435.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A.; Egorova, N.; Balbierz, A.; Zeitlin, J.; Hebert, P.L. Black-White Differences in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Site of Care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 122.e1–122.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tucker, M.J.; Berg, C.J.; Callaghan, W.M.; Hsia, J. The Black-White Disparity in Pregnancy-Related Mortality from 5 Conditions: Differences in Prevalence and Case-Fatality Rates. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e254–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creanga, A.A. Maternal Mortality in the United States. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Definition of Primary Care Provider. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/primary-care-provider (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Ogunwole, S.M.; Chen, X.; Mitta, S.; Minhas, A.; Sharma, G.; Zakaria, S.; Vaught, A.J.; Toth-Manikowski, S.M.; Smith, G. Interconception Care for Primary Care Providers: Consensus Recommendations on Preconception and Postpartum Management of Reproductive-Age Patients with Medical Comorbidities. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2021, 5, 872–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starfield, B.; Shi, L.; Macinko, J. Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 457–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Chang, H.-Y.; Levine, D.M.; Wang, L.; Neale, D.; Werner, E.F.; Clark, J.M. Utilization of Primary and Obstetric Care after Medically Complicated Pregnancies: An Analysis of Medical Claims Data. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice Committee Opinion No. 649: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 126, e130–e134. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Berra, K.; Bezanson, J.L.; Dolor, R.J.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Newby, L.K.; Piña, I.L.; Roger, V.L.; Shaw, L.J.; et al. Effectiveness-Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women-2011 Update: A Guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011, 123, 1243–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryant, A.; Ramos, D.; Stuebe, A.; Blackwell, S.C. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 8: Interpregnancy Care. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, E51–E72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auguste, T.; Gulati, M. Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e140–e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, L.; Bernstein, J.; The Bridging the Chasm Collaborative; Amutah-Onukagha, N.; Anthony, J.; Barger, M.; Belanoff, C.; Bennett, T.; Bird, C.E.; Bolds, D.; et al. Bridging the Chasm between Pregnancy and Health over the Life Course: A National Agenda for Research and Action. Womens Health Issues 2021, 31, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care Patient Safety Bundle. Postpartum Care Basics for Maternal Safety Readiness: Transition from Maternity to Well-Woman Care; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, M.; Chan, C.S.; Frayne, S.M.; Panelli, D.M.; Phibbs, C.S.; Shaw, J.G. Postpartum Transition of Care: Racial/Ethnic Gaps in Veterans’ Re-Engagement in VA Primary Care after Pregnancy. Womens Health Issues 2021, 31, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Ennen, C.S.; Carrese, J.A.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Levine, D.M.; Nicholson, W.K.; Clark, J.M. Barriers to and Facilitators of Postpartum Follow-up Care in Women with Recent Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Qualitative Study. Proc. J. Women Health 2011, 20, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bryant, A.; Blake-Lamb, T.; Hatoum, I.; Kotelchuck, M. Women’s Use of Health Care in the First 2 Years Postpartum: Occurrence and Correlates. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, V.K.; Amamoo, M.A.; Anderson, A.D.; Webb, D.; Mathews, L.; Rowley, D.; Culhane, J.F. Barriers to Women’s Participation in Inter-Conceptional Care: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, C.P. Levels of Racism: A Theoretic Framework and a Gardener’s Tale. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1213–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions. The Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.T.; Mohammed, S.A.; Williams, D.R. Racial Discrimination & Health: Pathways & Evidence. Indian J. Med. Res. 2007, 126, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prather, C.; Fuller, T.R.; Marshall, K.J.; Jeffries, W.L. The Impact of Racism on the Sexual and Reproductive Health of African American Women. J. Womens Health 2002 2016, 25, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clay, S.L.; Griffin, M.; Averhart, W. Black/White Disparities in Pregnant Women in the United States: An Examination of Risk Factors Associated with Black/White Racial Identity. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Lewis Johnson, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J. Womens Health 2002 2021, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A.; Egorova, N.N.; Balbierz, A.; Zeitlin, J.; Hebert, P.L. Site of Delivery Contribution to Black-White Severe Maternal Morbidity Disparity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janevic, T.; Sripad, P.; Bradley, E.; Dimitrievska, V. “There’s No Kind of Respect Here”: A Qualitative Study of Racism and Access to Maternal Health Care among Romani Women in the Balkans. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Rosenthal, L.; Lewis, J.B.; Stasko, E.C.; Tobin, J.N.; Lewis, T.T.; Reid, A.E.; Ickovics, J.R. Maternal Experiences with Everyday Discrimination and Infant Birth Weight: A Test of Mediators and Moderators among Young, Urban Women of Color. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehra, R.; Boyd, L.M.; Ickovics, J.R. Racial Residential Segregation and Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 191, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.N.; Ayanian, J.Z. Perceived Discrimination and Use of Preventive Health Services. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnett, M.J.; Thorpe, R.J.; Gaskin, D.J.; Bowie, J.V.; LaVeist, T.A.; LaVeist, T.A. Race, Medical Mistrust, and Segregation in Primary Care as Usual Source of Care: Findings from the Exploring Health Disparities in Integrated Communities Study. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2016, 93, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.; Ayers, S.L.; Kronenfeld, J.J. The Association between Perceived Provider Discrimination, Healthcare Utilization and Health Status in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Ethn. Dis. 2009, 19, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ben, J.; Cormack, D.; Harris, R.; Paradies, Y. Racism and Health Service Utilisation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Ters, M.; Schears, G.J.; Taler, S.J.; Williams, A.W.; Albright, R.C.; Jenson, B.M.; Mahon, A.L.; Stockland, A.H.; Misra, S.; Nyberg, S.L.; et al. Association between Prior Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters and Lack of Functioning Arteriovenous Fistulas: A Case-Control Study in Hemodialysis Patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2012, 60, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dehkordy, S.F.; Hall, K.S.; Dalton, V.K.; Carlos, R.C. The Link between Everyday Discrimination, Healthcare Utilization, and Health Status among a National Sample of Women. J. Womens Health 2002 2016, 25, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogan, V.K.; Culhane, J.F.; Crews, K.J.; Mwaria, C.B.; Rowley, D.L.; Levenstein, L.; Mullings, L.P. The Impact of Social Disadvantage on Preconception Health, Illness, and Well-Being: An Intersectional Analysis. Am. J. Health Promot. 2013, 27, eS32–eS42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, T.K. Performing Black Womanhood: A Qualitative Study of Stereotypes and the Healthcare Encounter. Crit. Public Health 2017, 28, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, Y.A.; Limonta, N.R.G. The Importance of Black Feminism and the Theory of Intersectionality in Analysing the Position of Afro Descendants. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Hamilton, M.F. Theoretical Frameworks for African American Women. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2003, 2003, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-winters, V.E.; Esposito, J. Other People’s Daughters: Critical Race Feminism and Black Girls’ Education. Educ. Found. 2010, 24, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal, L. What Is Critical Race Feminism? Buffalo Hum. Rights Law Rev. 1998, 4, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, R.; Jean, S. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction; New Yok University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-8147-2136-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio, M.; Russell, C.; Rios, F.; Bridgeman, J.L. Critical Race Theory Matters: Education and Ideology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-203-84271-3. [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano, D. Images and Words That Wound: Critical Race Theory, Racial Stereotyping, and Teacher Education. Teach. Educ. Q. 1997, 24, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins, P. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-74317-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, C.L.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Commentary: Just What Is Critical Race Theory and What’s It Doing in a Progressive Field like Public Health? Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, C.L. Public Health Critical Race Praxis: An Introduction, an Intervention, and Three Points for Consideration. Wis. Law Rev. 2016, 2016, 477–491. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, N.; Saleh, N. Applying Critical Race Feminism and Intersectionality to Narrative Inquiry: A Point of Resistance for Muslim Nurses Donning a Hijab. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 42, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Vogelsang, C.A.; Hardeman, R.R.; Prasad, S. Disrupting the Pathways of Social Determinants of Health: Doula Support during Pregnancy and Childbirth. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Geller, A.; Negussie, Y.; Baciu, A. (Eds.) Communities in Action; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-309-45296-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, L.; Lobel, M. Gendered Racism and the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Black and Latina Women. Ethn. Health 2018, 25, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullings, L. Resistance and Resilience: The Sojourner Syndrome and the Social Context of Reproduction in Central Harlem. Transform. Anthropol. 2005, 13, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Boyd, L.M.; Magriples, U.; Kershaw, T.S.; Ickovics, J.R.; Keene, D.E. Black Pregnant Women “Get the Most Judgment”: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Black Women at the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Pregnancy. Womens Health Issues 2020, 30, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitsch, B.; Gohl, D.; von Lengerke, T. Re-Revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: A Systematic Review of Studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2012, 9, Doc11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gelberg, L.; Andersen, R.M.; Leake, B.D. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: Application to Medical Care Use and Outcomes for Homeless People. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 34, 1273–1302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oser, C.B.; Bunting, A.M.; Pullen, E.; Stevens-Watkins, D. African American Female Offender’s Use of Alternative and Traditional Health Services After Re-Entry: Examining the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations HHS Public Access. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 120–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cibula, D.A.; Novick, L.F.; Morrow, C.B.; Sutphen, S.M. Community Health Assessment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003, 24, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltimore Tries Drastic Plan of Race Segregation. The New York Times. 25 December 1910. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1910/12/25/archives/baltimore-tries-drastic-plan-of-race-segregation-strange-situation.html (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Power, G. Apartheid Baltimore Style: The Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910–1913. Md. Rev. 1983, 42, 289–328. [Google Scholar]

- Pietila, A. Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City; Illustrated Edition; Ivan R. Dee: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-56663-843-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, L.; Rutherford, B.K.; Neall, R.R. Maryland Maternal Mortality Review 2019 Annual Report; Maryland Department of Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J. Something Old, Something New: The Syndemic of Racism and COVID-19 and Its Implications for Medical Education. Fam. Med. 2020, 52, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisler, C.; Swarts, J. Chapter 5. Achieving Reliability. In Coding Streams of Language: Techniques for the Systematic Coding of Text, Talk, and Other Verbal Data; The WAC Clearinghouse: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2020; pp. 155–202. ISBN 978-1-60732-730-1. [Google Scholar]

- The Family Tree Kids Care plus Flexible Child Care. Available online: https://familytreemd.org/kidscareplus/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Brown, A.F.; Ma, G.X.; Miranda, J.; Eng, E.; Castille, D.; Brockie, T.; Jones, P.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Farhat, T.; Zhu, L.; et al. Structural Interventions to Reduce and Eliminate Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, S72–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.A.M.; Young, Y.Y.; Bass, T.M.; Baker, S.; Njoku, O.; Norwood, J.; Simpson, M. Racism Runs through It: Examining the Sexual and Reproductive Health Experience of Black Women in the South. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder, K.; White, K.O.; Woodhams, E.; Pancholi, R.; Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L. Racism and the Reproductive Health Experiences of U.S.-Born Black Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhara, K.S.; Ehmann, M.R.; Irvin, N. Antiracism in Health Professions Education Through the Lens of the Health Humanities. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, R.R.; Burgess, D.; Murphy, K.; Satin, D.J.; Nielsen, J.; Potter, T.M.; Karbeah, J.; Zulu-Gillespie, M.; Apolinario-Wilcoxon, A.; Reif, C.; et al. Developing a Medical School Curriculum on Racism: Multidisciplinary, Multiracial Conversations Informed by Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP). Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedEdPORTAL Anti-Racism Education Collection. Available online: https://www.mededportal.org/anti-racism (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Crews, D.C.; Collins, C.A.; Cooper, L.A. Distinguishing Workforce Diversity from Health Equity Efforts in Medicine. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e214820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanGompel, E.W.; Lai, J.S.; Davis, D.A.; Carlock, F.; Camara, T.L.; Taylor, B.; Clary, C.; McCorkle-Jamieson, A.M.; McKenzie-Sampson, S.; Gay, C.; et al. Psychometric Validation of a Patient-Reported Experience Measure of Obstetric Racism© (The PREM-OB ScaleTM Suite). Birth 2022, 49, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods-Giscombé, C.L. Superwoman Schema: African American Women’s Views on Stress, Strength, and Health. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hardeman, R.R.; Kheyfets, A.; Mantha, A.B.; Cornell, A.; Crear-Perry, J.; Graves, C.; Grobman, W.; James-Conterelli, S.; Jones, C.; Lipscomb, B.; et al. Developing Tools to Report Racism in Maternal Health for the CDC Maternal Mortality Review Information Application (MMRIA): Findings from the MMRIA Racism & Discrimination Working Group. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centering Healthcare Institute|CenteringPregnancy. Available online: https://centeringhealthcare.org/what-we-do/centering-pregnancy (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Paladine, H.L.; Blenning, C.E.; Strangas, Y. Postpartum Care: An Approach to the Fourth Trimester. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, M.E.M.; Fisher, M.A.; Prifti, C.A.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Yarrington, C.D.; White, K.O.; Battaglia, T.A. Primary Care–Based Cardiovascular Disease Risk Management after Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Narrative Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Postpartum Care for Women up to One Year after Pregnancy; Evidence-Based Practice Center Systematic Review; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Rockville, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.N.; Pudwell, J.; Roddy, M. The Maternal Health Clinic: A New Window of Opportunity for Early Heart Disease Risk Screening and Intervention for Women with Pregnancy Complications. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2013, 35, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Pittsburgh Postpartum Hypertension Center. Available online: https://www.upmc.com/locations/hospitals/magee/services/heart-center/postpartum-hypertension-program (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Einstein Healthcare Network Women’s Cardiovascular Program. Available online: https://es.einstein.edu/cardiology/programs/womens-cardio (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Triebwasser, J.E.; Lewey, J.; Walheim, L.; Srinivas, S.K. Nudge Intervention to Transition Care after Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S245–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.L.; Perez, S.L.; Walker, A.; Estriplet, T.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Auguste, T.C.; Crear-Perry, J.A. The Cycle to Respectful Care: A Qualitative Approach to the Creation of an Actionable Framework to Address Maternal Outcome Disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Respectful Maternity Care Implementation Toolkit. Available online: https://www.awhonn.org/respectful-maternity-care-implementation-toolkit/ (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Murrell, N.L.; Smith, R.; Gill, G.; Oxley, G. Racism and Health Care Access: A Dialogue with Childbearing Women. Health Care Women Int. 1996, 17, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of American Medical Colleges Figure 18. Percentage of All Active Physicians by Race/Ethnicity. 2018. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Association of American Medical Colleges Figure 19. Percentage of Physicians by Sex. 2018. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-20-percentage-physicians-sex-and-race/ethnicity-2018 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Kaplan, S.E.; Gunn, C.M.; Kulukulualani, A.K.; Raj, A.; Freund, K.M.; Carr, P.L. Challenges in Recruiting, Retaining and Promoting Racially and Ethnically Diverse Faculty. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2018, 110, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkson-Ocran, R.A.N.; Michelle Ogunwole, S.; Hines, A.L.; Peterson, P.N. Shared Decision Making in Cardiovascular Patient Care to Address Cardiovascular Disease Disparities. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Hutchison, M.; Castro, G.; Nau, M.; Shumway, M.; Stotland, N.; Spielvogel, A. Meeting Women Where They Are: Integration of Care as the Foundation of Treatment for at-Risk Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 21, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye, E.; Sharma, G.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Zakaria, S.; Vaught, A.J.; Kwapong, Y.A.; Hong, X.; Ji, Y.; Mehta, L.; Creanga, A.A.; et al. Relationship of Preeclampsia with Maternal Place of Birth and Duration of Residence among Non-Hispanic Black Women in the United States. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2021, 14, e007546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwapong, Y.A.; Boakye, E.; Obisesan, O.H.; Shah, L.M.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Hays, A.G.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Creanga, A.A.; Blaha, M.J.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; et al. Nativity-Related Disparities in Preterm Birth and Cardiovascular Risk in a Multiracial U.S. Cohort. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunwole, S.M.; Turkson-Ocran, R.-A.N.; Boakye, E.; Creanga, A.A.; Wang, X.; Bennett, W.L.; Sharma, G.; Cooper, L.A.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Disparities in Cardiometabolic Risk Profiles and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus by Nativity and Acculturation: Findings from 2016–2017 National Health Interview Survey. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e002329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradies, Y.; Ben, J.; Denson, N.; Elias, A.; Priest, N.; Pieterse, A.; Gupta, A.; Kelaher, M.; Gee, G. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creanga, A.A.; Bateman, B.T.; Mhyre, J.M.; Kuklina, E.; Shilkrut, A.; Callaghan, W.M. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 211, 647.E1–647.E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.K. Structural Racism and Maternal Health among Black Women. J. Law Med. Ethics 2020, 48, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, T.P. Adverse Birth Outcomes in African American Women: The Social Context of Persistent Reproductive Disadvantage. Soc. Work Public Health 2011, 26, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NPR/Propublica. Lost Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the U.S. 2018. Available online: https://www.npr.org/series/543928389/lost-mothers (accessed on 6 April 2019).

- Structural Racism and Discrimination. Available online: https://nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/srd.html (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Cross, R.I. Commentary: Can critical race theory enhance the field of public health? A student’s perspective. Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Social and Demographic | ||

| Maternal age, years; range, (mean) | 18 | 23–43 (31.7) |

| Yearly Income ($) | ||

| <15,000 | 5 | 27.8 |

| 15,000–29,000 | 3 | 16.7 |

| 30,000–49,000 | 4 | 22.2 |

| >50,000 | 4 | 22.2 |

| I don’t know | 2 | 11.11 |

| Pre-pregnancy Chronic Medical Conditions | ||

| Diabetes | 1 | 5.6 |

| High blood pressure | 6 | 33.3 |

| Obesity | 12 | 66.7 |

| Sickle cell trait | 3 | 16.7 |

| Depression | 9 | 50.0 |

| Anxiety | 10 | 55.6 |

| Other | 7 | 38.9 |

| Pregnancy-Related Comorbidities | ||

| Gestational Diabetes | ||

| Yes | 5 | 27.8 |

| Gestational High Blood Pressure | ||

| Yes | 9 | 50.0 |

| Healthcare Utilization and Access | ||

| Health Insurance Before Pregnancy | ||

| No Insurance | 1 | 5.6 |

| Medicaid | 14 | 77.8 |

| Private Health Insurance | 3 | 16.7 |

| Health Insurance After Pregnancy | ||

| No Insurance | 0 | 0.0 |

| Medicaid | 15 | 83.3 |

| Private Health Insurance | 2 | 11.1 |

| Other Insurance | 1 | 5.6 |

| Theme | Subtheme | Opportunities for Intervention at the following Levels: Provider (P), Community (C), System (S) + |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to Postpartum Care Transitions | “I Didn’t Think I Needed to See My Primary Care Doctor:” Limited Patient Knowledge about Postpartum Health Needs following Cardiometabolic Complication of Pregnancy and Role of Primary Care Providers. |

|

| Lack of “Information Sharing” between Obstetric and Primary Care Providers. |

| |

| Facilitator of Postpartum Care Transitions: Patient-Provider Relationships | “Not Just Another Chart”: Patient-Centered Care, Humanistic Care and Individuation Improved Experiences of Care. | |

| “I Keep Him in the Loop”: Preconception Relationships Improve Care Continuity and Communication. |

| |

| “I Didn’t Have to Put on a Professional Face”: Racial and Gender Concordance Supports Open Communication. |

| |

| Postpartum Health and Healthcare Needs | “Postpartum is No Joke”: Lack of Preparation for Unique Mental Health and Social Support Needs Emerge Postpartum. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogunwole, S.M.; Oguntade, H.A.; Bower, K.M.; Cooper, L.A.; Bennett, W.L. Health Experiences of African American Mothers, Wellness in the Postpartum Period and Beyond (HEAL): A Qualitative Study Applying a Critical Race Feminist Theoretical Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136283

Ogunwole SM, Oguntade HA, Bower KM, Cooper LA, Bennett WL. Health Experiences of African American Mothers, Wellness in the Postpartum Period and Beyond (HEAL): A Qualitative Study Applying a Critical Race Feminist Theoretical Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136283

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgunwole, S. Michelle, Habibat A. Oguntade, Kelly M. Bower, Lisa A. Cooper, and Wendy L. Bennett. 2023. "Health Experiences of African American Mothers, Wellness in the Postpartum Period and Beyond (HEAL): A Qualitative Study Applying a Critical Race Feminist Theoretical Framework" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136283

APA StyleOgunwole, S. M., Oguntade, H. A., Bower, K. M., Cooper, L. A., & Bennett, W. L. (2023). Health Experiences of African American Mothers, Wellness in the Postpartum Period and Beyond (HEAL): A Qualitative Study Applying a Critical Race Feminist Theoretical Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136283