Understanding Key Predictors of Life Satisfaction in a Nationally Representative Sample of Koreans

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Sociodemographic Factors and Life Satisfaction

1.3. Psychosocial Factors and Life Satisfaction

1.4. Current Study

2. Methods

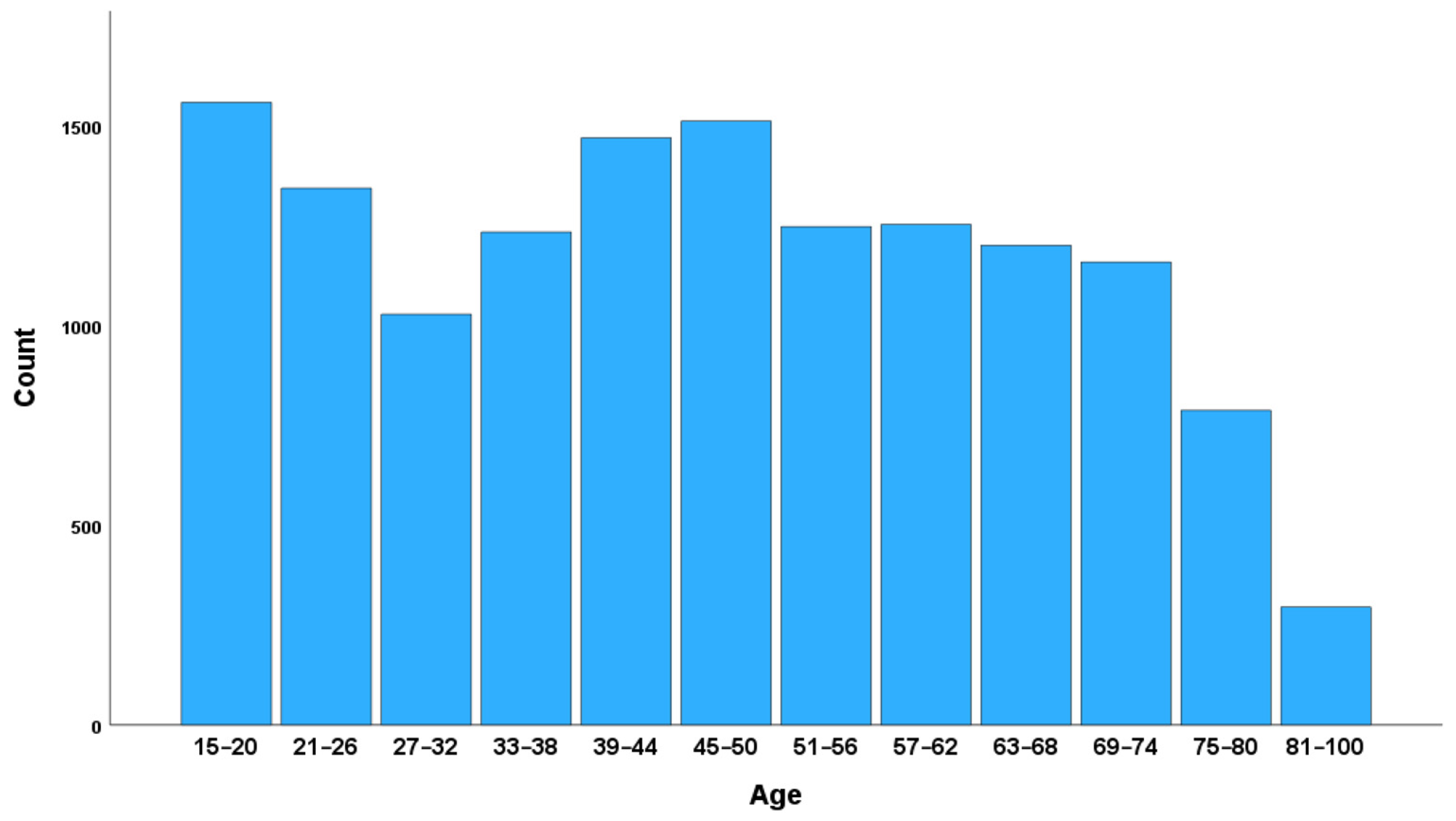

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

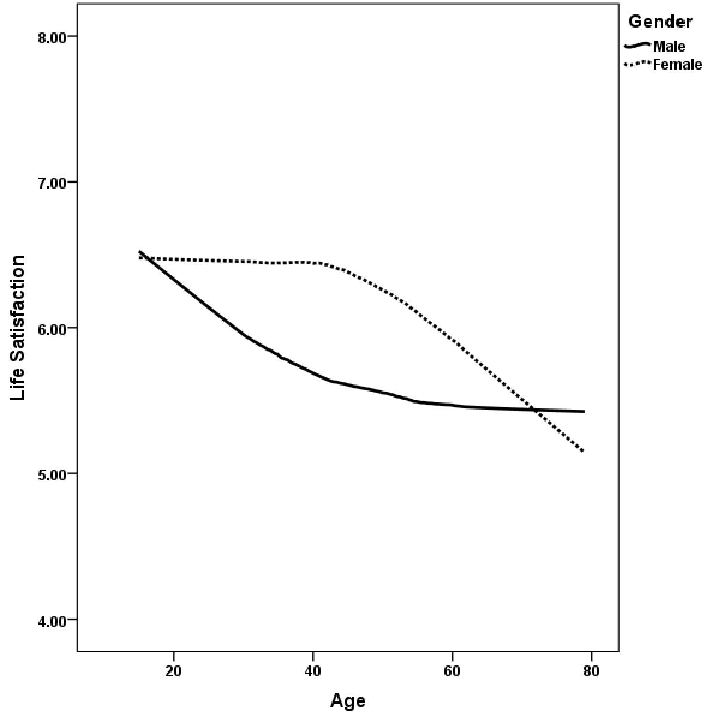

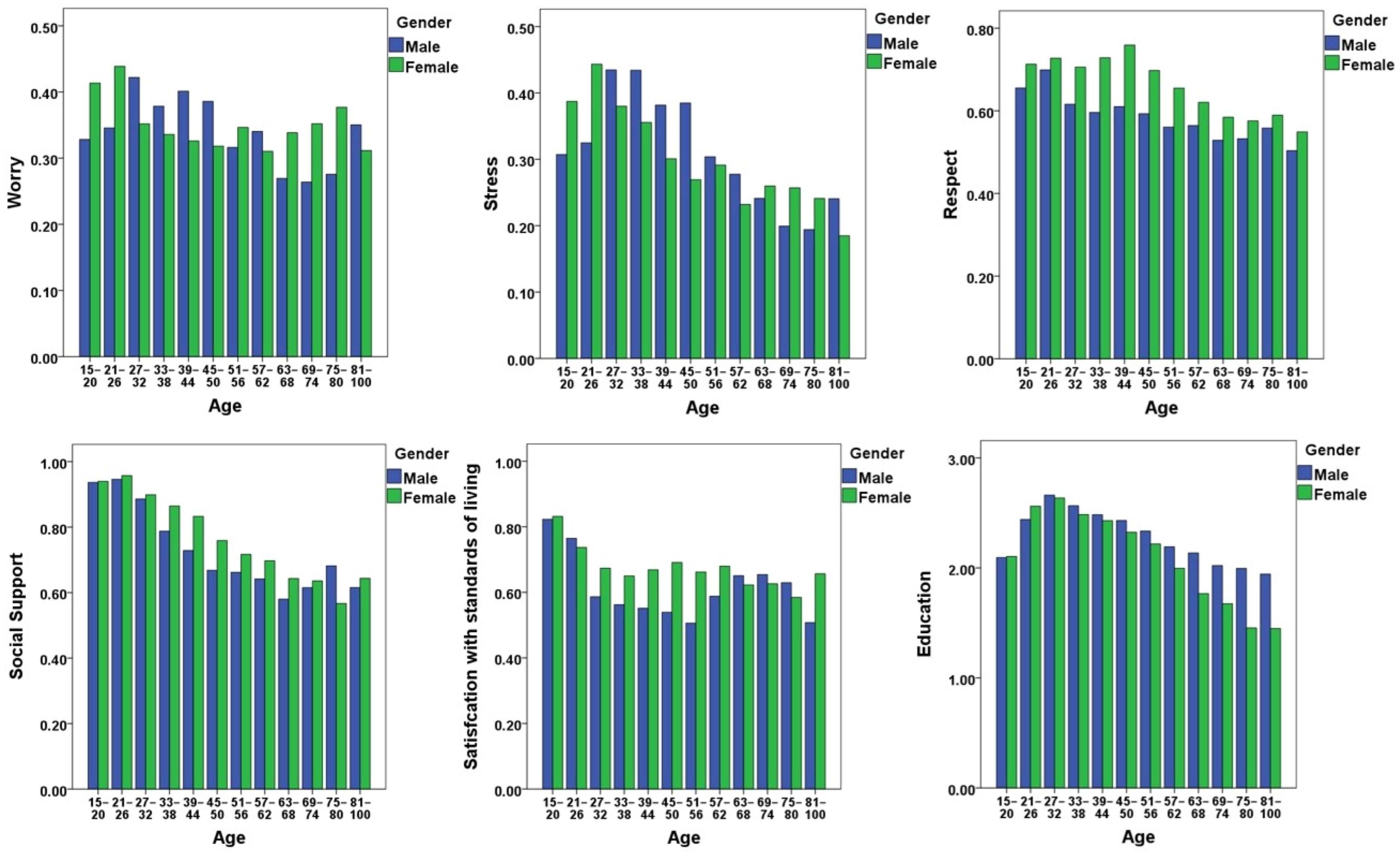

3.2. How Does Life Satisfaction Vary in Korea by Age and Gender?

3.3. Explaining Age and Gender Differences in Life Satisfaction

3.4. Other Demographic Predictors of Life Satisfaction

3.5. Comprehensive Prediction of Life Satisfaction

3.6. Relationship between Household Income and Life Satisfaction: A Close Examination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauer, J.M.; Levin, V.; Munoz Boudet, A.M.; Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A. Subjective well-being across the lifespan in Europe and Central Asia. J. Popul. Ageing 2017, 10, 125–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: Americans’ Perceptions of Life Quality; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.W.; Cha, K.H. Analyses on the construct of psychological well-being of Korean male and female adults. Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2001, 15, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.M.; Kim, S.Y. Quality of life in Korea: Global, domain-specific and standards of comparison. J. Asiat. Stud. 2002, 45, 141–464. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.E.; Kim, S. Personality and subjective well-being: Evidence from South Korea. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Shaver, P.R.; Sue, S.; Min, K.H.; Jing, H. Culture-specific patterns in the prediction of life satisfaction: Roles of emotion, relationship quality, and self-esteem. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1596–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.C.; Sanna, L.J.; Yang, K.M. Optimism, pessimism, affectivity, and psychological adjustment in US and Korea: A test of a mediation model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calasanti, T.; Carr, D.; Homan, P.; Coan, V. Gender disparities in life satisfaction after retirement: The roles of leisure, family, and finances. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Lous, B. Income inequality, life satisfaction inequality and trust: A cross country panel analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1717–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, K.; Oshio, T. Multidimensional poverty and perceived happiness: Evidence from China, Japan and Korea. J. Asian. Econ. 2016, 30, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Torreblanca, E.G.; Brown, G.D.; Boyce, C.J.; Wood, A.M.; De Neve, J.E. Inequality and social rank: Income increases buy more life satisfaction in more equal countries. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 47, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health & Welfare. White Paper on Suicide Prevention; No. 11-1352000-001635-10; Korea Foundation for Suicide Prevention: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J. World Happiness Report 2013; UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J. World Happiness Report 2015; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, D.J. World Happiness Report 2018; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; Aknin, L.B.; De Neve, J.-E.; Wang, S. World Happiness Report 2023, 11th ed.; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.M. Korea’s Economy Expected to Remain in the Top 10 in the World for Three Consecutive Years. Yonhap News, 26 December 2021. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20211224134000009(accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Diego-Rosell, P.; Tortora, R.; Bird, J. International determinants of subjective well-being: Living in a subjectively material world. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M. Income satisfaction is less predictive of life satisfaction in individuals who believe their lives have meaning or purpose: A 94-nation study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 129, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P.; Realo, A.; Diener, E. The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.S. Study on the determinants on life satisfaction according to the generation: Focused on the moderating effects of generation difference. Inst. Soc. Sci. Chungnam Natl. Univ. 2019, 30, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckermeier, L.C. The value of autonomy for the good life: An empirical investigation of autonomy and life satisfaction in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 154, 693–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.; Stutzer, A. The economics of happiness. World Econ. 2002, 3, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, C.J.; Brown, G.D.; Moore, S.C. Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamaba, K.H.; Panagioti, M.; Armitage, C.J. Income inequality and subjective well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzRoy, F.R.; Nolan, M.A. Income status and life satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G. Correlates of quality of life, happiness and life satisfaction among European adults older than 50 years: A machine-learning approach. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 103, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, R.A. Personal Income and Subjective Well-being: A Review. J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 1, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Joshanloo, M.; Scheifinger, H. Predictors of life satisfaction in a large nationally representative Japanese sample. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 82, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanović, V.; Joshanloo, M. The determinants of life satisfaction in Serbia: Findings from the Gallup World Poll. Int. J. Wellbeing 2019, 9, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Joshanloo, M.; Scheifinger, H. Predictors of life satisfaction in Australia: A study drawing upon annual data from the Gallup World Poll. Aust. Psychol. 2020, 55, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.; Karabchuk, T.; Joshanloo, M. Predictors of life satisfaction in the United Arab Emirates: Results based on Gallup data. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 3827–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.A.; Joshanloo, M. Satisfaction with life declines with age in Malaysia: An exploratory analysis of factors influencing subjective well-being in a developing/middle-income country. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V.; Joshanloo, M.; Scheifinger, H. Predictors of life satisfaction in a large representative sample from Italy. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3609–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarden, R.J.; Joshanloo, M.; Weijers, D.; Sandham, M.H.; Jarden, A.J. Predictors of life satisfaction in New Zealand: Analysis of a national dataset. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Income, Health, and Well-Being around the World: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Research Institute, KOSTAT. Quality of Life Indicators in Korea 2022. 2023. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=b10105000000&bid=0060&act=view&list_no=426074&tag=&nPage=1&ref_bid= (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Schaefer, C.; Coyne, J.C.; Lazarus, R.S. The health-related functions of social support. J. Behav. Med. 1981, 4, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siedlecki, K.L.; Salthouse, T.A.; Oishi, S.; Jeswani, S. The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soylu, C. Predictors of domain-specific and global life satisfaction across the first half of life: Which domains of life satisfaction are the most important for global life satisfaction? Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19443–19454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, E.M.; Oishi, S. Culture and subjective well-being: Introduction to the special issue. J. Happiness Stud. 2004, 5, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantril, H. Pattern of Human Concerns; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, N.; Helliwell, J.F.; Wang, S. How does subjective well-being vary around the world by gender and age? In World Happiness Report; Helliwell, J.F., Layard, R., Sachs, J., Eds.; Earth Institute, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 42–75. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kashdan, T.B. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth, and Crisis; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. Gender difference in influencing factors on health related quality of life among the elderly in community. J. Digit. Converg. 2013, 11, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C. Can academic credentials determine life satisfaction?: The estimates on the non-monetary effects of academic credentials. Korean J. Econ. Stud. 2016, 64, 107–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S. Exploratory study for development tasks and beginning time of early adulthood. Korean J. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 21, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.J.; Lee, H. A Study on factors affecting quality of life for the elderly: Focusing on socio-demographic, environmental, and institutional characteristics. J. Korean Soc. Wellness 2019, 14, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.P.; Lim, H.R. Analysis of changes in life satisfaction and influence factors in single-person households of middle-aged and elderly people: Comparative analysis of middle-aged and elderly people with multi-person households. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2022, 42, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chow, A.Y.; Tang, S. Trajectories of depression symptoms in Chinese elderly during widowhood: A secondary analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Hülür, G. Life Satisfaction during the Transition to Widowhood among Japanese Older Adults. Gerontology 2021, 67, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Jang, Y.S.; Cho, H.S.; Cha, M.S. A Study of Determinants and Indicators of Happiness among Koreans; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008; pp. 64–190. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Golpelwar, M. Testing subjective well-being from the perspective of social quality: Quantile regression evidence from Shanghai, China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.Y.; Lee, C.M. A study of the income satiation point of happiness among Koreans. Korean Soc. Secur. Stud. 2022, 38, 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.A.; Jung, H.S. The determinants of life satisfaction in different age groups and their policy implications. Health Welf. Policy Forum 2019, 2019, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, E.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.J. Factors influencing the quality of life by gender in Korean youth (19–34 years old): Using data from the 7th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2016–2017). Korean Soc. Health Serv. Manag. 2021, 15, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcionetti, J.; Rossier, J. A longitudinal study of relations among adolescents’ self-esteem, general self-efficacy, career adaptability, and life satisfaction. J. Career Dev. 2021, 48, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakar, F.S. The relationship between the self-efficacy and life satisfaction of young adults. Int. Educ. Stud. 2012, 5, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Old-Age Income Poverty. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/d76e4fad-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/d76e4fad-en (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Kim, M.H. Relationship between preparation for old age and psychological well-being of middle adult: Serial multiple mediating effects of aging anxiety and perceived stress. Korean J. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 33, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Trends and causes of subjective well-being in Korea: Focusing on differences by gender and age. Korean Policy Sci. Rev. 2020, 24, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lim, J.Y.; Yoo, S.H. A Study of Youth Socio-Economic Reality and Policy Direction III (No. 18-R06); National Youth Policy Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Variable | Item Used | Response Format |

|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to ten at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time? | 00 Worst possible to 10 best possible |

| Enjoyment | Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about Enjoyment? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Worry | Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about Worry? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Sadness | Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about Sadness? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Stress | Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about Stress? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Anger | Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about Anger? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Laughter | Did you smile or laugh a lot yesterday? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Freedom | In (this country), are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life? | 1 Satisfied |

| 2 Dissatisfied | ||

| Safe at night | Do you feel safe walking alone at night in the city or area where you live? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Respect | Were you treated with respect all day yesterday? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Learned | Did you learn or do something interesting yesterday? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Satisfaction with city | Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the city or area where you live? | 1 Satisfied |

| 2 Dissatisfied | ||

| Household income satisfaction | Which one of these phrases comes closest to your own feelings about your household’s income these days? | 1 Living comfortably on present income |

| 2 Getting by on present income | ||

| 3 Finding it difficult on present income | ||

| 4 Finding it very difficult on present income | ||

| Health problems | Do you have any health problems that prevent you from doing any of the things people your age normally can do? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Social support | If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Satisfaction with standards of living | Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your standard of living, all the things you can buy and do? | 1 Satisfied |

| 2 Dissatisfied | ||

| Donated | Have you done any of the following in the past month? Donated money to a charity. | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Volunteered | Have you done any of the following in the past month? Volunteered your time to an organization | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Helped | Have you done any of the following in the past month? Helped a stranger or someone you didn’t know who needed help | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Corruption in business | Is corruption widespread within businesses located in Korea, or not? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No | ||

| Corruption in government | Is corruption widespread throughout the government in Korea, or not? | 1 Yes |

| 2 No |

| M | SD | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment | Employed full time for an employer | 6.007 | 1.936 | 2952 |

| df = 5, 10,803 F = 17.655 p < 0.001 η2 = 0.008 | Employed full time for self | 5.660 | 2.242 | 1256 |

| Employed part-time do not want full time | 6.317 | 2.064 | 794 | |

| Unemployed | 5.385 | 2.324 | 405 | |

| Employed part-time want full time | 5.539 | 2.378 | 406 | |

| Out of workforce | 5.956 | 2.255 | 4990 | |

| Total | 5.925 | 2.173 | 10,803 | |

| Education | Elementary | 4.908 | 2.796 | 1429 |

| df = 2, 13,816 F = 320.037 p < 0.001 η2 = 0.044 | Secondary | 5.701 | 2.112 | 7478 |

| Tertiary (four years beyond high school) | 6.389 | 1.869 | 4912 | |

| Total | 5.864 | 2.161 | 13,819 | |

| Location | Rural or farm | 5.231 | 2.399 | 1366 |

| df = 3, 13,855 F = 48.936 p < 0.001 η2 = 0.010 | Small town or village | 5.746 | 2.136 | 1767 |

| Large city | 5.954 | 2.119 | 6905 | |

| Suburb of a large city | 5.978 | 2.116 | 3821 | |

| Total | 5.863 | 2.161 | 13,859 | |

| Religious affiliation | Christian | 6.142 | 2.162 | 4213 |

| df = 3, 11,793 F = 30.909 p < 0.001 η2 = 0.008 | Buddhist | 5.661 | 2.240 | 2184 |

| Secular/non-religious | 5.802 | 2.104 | 5073 | |

| Other | 5.725 | 2.253 | 327 | |

| Total | 5.895 | 2.163 | 11,797 | |

| Relationship status | Single | 6.082 | 1.968 | 4164 |

| df = 2, 13,484 F = 100.714 p < 0.001 η2 = 0.015 | Married | 5.909 | 2.114 | 8572 |

| Widow | 4.895 | 2.742 | 751 | |

| Total | 5.907 | 2.126 | 13,487 |

| B | 95.0% CI for B | t | p | Beta | Semi-Partial Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Up | ||||||

| (Constant) | 2.341 | 2.034 | 2.649 | 14.920 | 0.000 | - | - |

| Female | 0.366 | 0.270 | 0.462 | 7.502 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.076 |

| Age | −0.008 | −0.011 | −0.005 | −5.782 | 0.000 | −0.072 | −0.059 |

| Age-squared | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.949 | 0.342 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| Positive affect | 0.341 | 0.213 | 0.468 | 5.233 | 0.000 | 0.066 | 0.053 |

| Negative affect | −0.658 | −0.819 | −0.497 | −8.030 | 0.000 | −0.093 | −0.081 |

| Social support | 0.362 | 0.249 | 0.474 | 6.301 | 0.000 | 0.071 | 0.064 |

| Helped | 0.124 | 0.031 | 0.216 | 2.622 | 0.009 | 0.028 | 0.027 |

| Volunteer | 0.218 | 0.109 | 0.328 | 3.910 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.040 |

| Donated | 0.096 | −0.001 | 0.193 | 1.937 | 0.053 | 0.021 | 0.020 |

| Freedom | 0.230 | 0.135 | 0.324 | 4.771 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.048 |

| Safe at night | −0.029 | −0.124 | 0.065 | −0.608 | 0.543 | −0.007 | −0.006 |

| Respect | 0.153 | 0.050 | 0.257 | 2.894 | 0.004 | 0.034 | 0.029 |

| Learning experience | 0.168 | 0.072 | 0.264 | 3.422 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.035 |

| Health problems | −0.121 | −0.230 | −0.013 | −2.198 | 0.028 | −0.024 | −0.022 |

| Satisfaction with city | 0.185 | 0.075 | 0.295 | 3.307 | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.033 |

| Corruption | −0.229 | −0.343 | −0.114 | −3.919 | 0.000 | −0.041 | −0.040 |

| Satisfaction w. stand. Of living | 0.956 | 0.846 | 1.066 | 17.032 | 0.000 | 0.206 | 0.172 |

| HH income satisfaction | 0.477 | 0.410 | 0.545 | 13.832 | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.140 |

| Education level | 0.292 | 0.216 | 0.368 | 7.548 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.076 |

| Rural | −0.117 | −0.272 | 0.037 | −1.489 | 0.137 | −0.016 | −0.015 |

| Small town or village | −0.104 | −0.252 | 0.045 | −1.372 | 0.170 | −0.014 | −0.014 |

| Widow | −0.333 | −0.532 | −0.135 | −3.288 | 0.001 | −0.037 | −0.033 |

| Work full time | 0.075 | −0.056 | 0.205 | 1.120 | 0.263 | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| Part-time, not looking for full time | 0.175 | −0.008 | 0.358 | 1.877 | 0.061 | 0.022 | 0.019 |

| Out of workforce | 0.044 | −0.080 | 0.168 | 0.695 | 0.487 | 0.010 | 0.007 |

| Christian | 0.121 | 0.020 | 0.221 | 2.359 | 0.018 | 0.027 | 0.024 |

| Buddhist | −0.066 | −0.188 | 0.057 | −1.052 | 0.293 | −0.012 | −0.011 |

| Gender | Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 15–24 | 25–44 | 45–64 | 65+ | |

| (Constant) | 2.239 *** | 2.776 *** | 3.642 *** | 3.480 *** | 1.575 *** | 1.908 *** |

| Female | - | - | 0.129 | 0.441 *** | 0.470 *** | 0.196 |

| Age | −0.009 *** | −0.008 *** | - | - | - | - |

| Age-squared | 0.000 ** | 0.000 | - | - | - | - |

| Positive affect | 0.364 *** | 0.316 ** | 0.419 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.405 *** | 0.188 |

| Negative affect | −0.664 *** | −0.628 *** | −0.646 *** | −0.986 *** | −0.364 * | −0.610 ** |

| Social support | 0.257 ** | 0.477 *** | 0.252 | 0.208 | 0.398 *** | 0.380 ** |

| Helped | 0.086 | 0.162 * | 0.160 | −0.010 | 0.197 * | 0.118 |

| Volunteer | 0.171 * | 0.267 *** | 0.277 * | 0.367 *** | 0.245 ** | 0.026 |

| Donated | 0.080 | 0.104 | 0.134 | 0.042 | 0.019 | 0.242 |

| Freedom | 0.219 ** | 0.238 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.308 *** | 0.215 * | 0.036 |

| Safe at night | 0.012 | −0.068 | −0.110 | −0.035 | 0.085 | −0.084 |

| Respect | 0.096 | 0.212 ** | 0.184 | 0.088 | 0.099 | 0.242 * |

| Learning experience | 0.157 * | 0.182 ** | 0.369 *** | 0.149 | 0.068 | 0.215 |

| Health problems | −0.143 | −0.101 | −0.046 | −0.224 * | −0.154 | −0.047 |

| Satisfaction with city | 0.139 | 0.229 ** | 0.193 | 0.092 | 0.214 * | 0.252 |

| Corruption | −0.219 ** | −0.247 ** | −0.285 * | −0.231 * | −0.151 | −0.296 * |

| Satisfaction w. stand. Of life | 0.926 *** | 0.986 *** | 0.812 *** | 0.901 *** | 0.916 *** | 1.229 *** |

| HH income satisfaction | 0.512 *** | 0.435 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.342 *** | 0.586 *** | 0.551 *** |

| Education level | 0.334 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.112 | 0.140 | 0.382 *** | 0.363 *** |

| Rural | −0.134 | −0.117 | −0.465 * | −0.240 | −0.166 | 0.088 |

| Small town or village | −0.075 | −0.120 | −0.182 | 0.003 | −0.139 | −0.193 |

| Widow | −0.552 ** | −0.196 | - | - | - | - |

| Work full time | 0.071 | 0.107 | 0.100 | 0.110 | 0.128 | −0.168 |

| Happy part-time, not looking for full time | 0.205 | 0.141 | −0.074 | 0.091 | 0.309 * | −0.008 |

| Out of workforce | −0.070 | 0.113 | −0.115 | 0.266 * | 0.049 | −0.117 |

| Christian | 0.152 * | 0.083 | 0.092 | 0.304 *** | 0.014 | 0.056 |

| Buddhist | −0.005 | −0.132 | −0.235 | 0.170 | −0.246 * | −0.035 |

| R2 | F | df | Most Important Predictors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 0.291 | 53.052 *** | 26, 3356 | SWSL, HH income, positive, education, and social support |

| Female | 0.310 | 58.290 *** | 26, 3374 | SWSL, HH income, positive, education, and social support |

| 15–24 | 0.226 | 13.865 *** | 24, 1139 | SWSL, positive, HH income, freedom, and learning experience |

| 25–44 | 0.317 | 34.337 *** | 24, 1779 | SWSL, positive, HH income, negative, and female |

| 45–64 | 0.331 | 45.220 *** | 24, 2198 | SWSL, positive, HH income, social support, and education |

| 65+ | 0.286 | 26.253 *** | 24, 1574 | SWSL, positive, HH income, social support, and education |

| Poorest 20% | 0.274 | 19.728 *** | 26, 1356 | SWSL, HH income, positive, age, and social support |

| Second 20% | 0.299 | 21.083 *** | 26, 1287 | SWSL, social support, positive, education, and HH income |

| Middle 20% | 0.298 | 20.367 *** | 26, 1248 | SWSL, positive, HH income, negative, and age |

| Fourth 20% | 0.242 | 16.214 *** | 26, 1324 | SWSL, HH income, positive, respect, and helped |

| Richest 20% | 0.245 | 18.006 *** | 26, 1440 | SWSL, HH income, positive, negative, and city satisfaction |

| M | SD | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Poorest 20% | 5.41 | 2.83 | 1880 |

| 2 Second 20% | 6.37 | 2.39 | 1991 |

| 3 Middle 20% | 6.68 | 2.18 | 1991 |

| 4 Fourth 20% | 6.97 | 2.04 | 2064 |

| 5 Richest 20% | 7.30 | 2.00 | 2273 |

| Total | 6.58 | 2.38 | 10,199 |

| Predictor | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 1.995 *** | 2.222 *** | 3.156 *** | 3.111 *** | 2.778 *** |

| Female | 0.151 | 0.554 *** | 0.301 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.337 ** |

| Age | −0.020 *** | −0.008 ** | −0.006 * | −0.004 | −0.003 |

| Age-squared | 0.000 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Positive affect | 0.563 ** | 0.274 | 0.358 * | 0.259 * | 0.290 * |

| Negative affect | −0.398 * | −0.833 *** | −0.813 *** | −0.583 ** | −0.702 *** |

| Social support | 0.412 ** | 0.519 *** | 0.240 | 0.113 | 0.333 * |

| Helped | −0.044 | 0.100 | 0.169 | 0.301 ** | 0.093 |

| Volunteer | 0.392 * | 0.264 * | 0.116 | 0.148 | 0.139 |

| Donated | 0.392 ** | −0.084 | −0.068 | −0.006 | 0.194 * |

| Freedom | 0.223 * | 0.110 | 0.182 | 0.268 ** | 0.321 ** |

| Safe at night | 0.071 | −0.111 | −0.268 ** | 0.074 | 0.095 |

| Respect | 0.134 | 0.164 | 0.132 | 0.285 ** | −0.048 |

| Learned | −0.084 | 0.344 ** | 0.029 | 0.198 * | 0.248 * |

| Health problems | 0.082 | −0.221 | −0.309 * | −0.142 | −0.048 |

| Satisfaction with city | 0.323 * | −0.022 | 0.292 * | 0.003 | 0.338 ** |

| Corruption | −0.282 | −0.252 | −0.276 * | −0.268 * | −0.057 |

| Satisfaction w. stand. Of life | 0.991 *** | 0.803 *** | 0.988 *** | 0.915 *** | 1.023 *** |

| HH income satisfaction | 0.436 *** | 0.370 *** | 0.461 *** | 0.484 *** | 0.427 *** |

| Education level | 0.353 ** | 0.441 *** | 0.158 | 0.131 | 0.092 |

| Rural | 0.157 | 0.037 | −0.296 | −0.297 | −0.352 |

| Small town or village | −0.130 | 0.108 | −0.211 | −0.117 | −0.131 |

| Work full time | −0.129 | 0.366 * | 0.083 | −0.075 | 0.174 |

| Happy part-time, not looking for full time | −0.180 | 0.500 * | 0.210 | −0.069 | 0.484 * |

| Out of workforce | −0.198 | 0.257 | 0.113 | 0.136 | 0.120 |

| Christian | 0.112 | 0.230 * | 0.061 | 0.017 | 0.161 |

| Buddhist | −0.133 | 0.104 | −0.287 * | −0.046 | −0.019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, Y.-K.; Joshanloo, M.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, H.-S.; Lee, H.-P.; Song, J. Understanding Key Predictors of Life Satisfaction in a Nationally Representative Sample of Koreans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186745

Choi Y-K, Joshanloo M, Lee J-H, Lee H-S, Lee H-P, Song J. Understanding Key Predictors of Life Satisfaction in a Nationally Representative Sample of Koreans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(18):6745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186745

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Yun-Kyeung, Mohsen Joshanloo, Jae-Ho Lee, Hong-Seock Lee, Heung-Pyo Lee, and Jonghwan Song. 2023. "Understanding Key Predictors of Life Satisfaction in a Nationally Representative Sample of Koreans" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 18: 6745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186745

APA StyleChoi, Y.-K., Joshanloo, M., Lee, J.-H., Lee, H.-S., Lee, H.-P., & Song, J. (2023). Understanding Key Predictors of Life Satisfaction in a Nationally Representative Sample of Koreans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(18), 6745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186745