Abstract

(1) Background: The main research aim of this paper is to investigate the commonly stocked medicines in Chinese households. Firstly, a large number of questionnaires were collected to uncover the problem: most Chinese families have the habit of stocking their family medicine boxes. However, there is a lack of a standardized, systematic, and scientific list of household medicine stockpiles. As a result, there are major problems in stocking medicines in households: (1) There is little connection between the type and quantity of medicines stocked and real life; (2) The expiration date of medicines leads to misuse and waste of medicines; (3) The existing list of medicines can provide little help. (2) Methods: The preliminary drug stock list was summarized through case studies; the authenticity of the questions and the credibility of the list were verified through interviews; the number of different types of drugs and the relationship between the resident’s perception of the importance of drugs and their frequency of use was determined through questionnaires; the authenticity of the list was verified through interviews with senior doctors. (3) Results: We finally composed a scientific and practical list of common household medicines, developed a practical domestic-medication system for Chinese families, and conducted validation studies, which received the approval of senior doctors. (4) Conclusions: (1) Chinese families need to prepare medicines according to the actual composition of the family; (2) Chinese families need a scientific and systematic list of commonly prepared medicines; and (3) in addition to the types of medicines, it is also necessary to consider the number of individual types of medicines to be stocked.

1. Introduction

About 78.6% of Chinese households have a family medicine cabinet [1], but the types of medicines stocked are not very relevant to the actual needs of life [2]. Especially in the post-epidemic era, in the face of regular epidemic management, the family medicine cabinet is often unable to fully cope with unexpected situations in life. The number of drug reserves is not completely consistent with the frequency and amount of use, which brings about the situation that many families want to use certain drugs, but the drugs stored at home have expired. Moreover, because more than 80% of the families do not have the habit of regularly cleaning the medicine boxes, the country produces about 15,000 tons of expired drugs in a year [1]. At present, China has not yet established a mature, scientific, and perfect recycling system for expired drugs [3,4,5], and such a serious waste of drugs is not conducive to the green and sustainable development of the environment. Therefore, solving the problem of expired drugs in household stockpiles is urgent. Existing studies on stocked medicines are based on the U.S. socio-medical situation [6,7,8,9] and are relatively old, with insufficient guidance for the 2020s after the outbreak of the COVID epidemic.

There is a wide range of domestic medicine lists in China, including the recommended list of household emergency supplies issued by the national emergency management department and specific recommendations based on that list [10], as well as recommendations from major authoritative health organizations and experienced physicians. These lists are similar in content but differ in detail, which causes some cognitive confusion for users. At the same time, these lists do not indicate the amount of each drug to be stocked, nor do they list the details according to the age [11,12,13], region [14,15,16], number, and structure [17,18,19] of the family and other aspects [20,21]. Therefore, we found that such a generalized list is of little reference for family practice.

In addition to this, many people tend to ignore the harmful effects of expired drugs on the body [4]. In fact, expired drugs are not only less effective or ineffective, but also may cause drug resistance, allergy, shock, and other adverse reactions [22]. For example, expired sulfonamides and penicillins are prone to allergies and shock; expired tetracycline contains degradation products that are tens of times more toxic than tetracycline and can lead to damage to kidney tubular function; nitroglycerin, which is used for angina first aid, is highly volatile and can easily fail due to improper storage, which will reduce its role in first aid, etc. If the storage method is changed, such as put in a high-temperature environment, humid environment, the cap is opened, etc., it will lead to moisture absorption, dehydration, mold, and changes in the chemical composition or structure of the drug, resulting in some decomposition products of unknown effect, in this case the expiration date of the drug can only be used as a reference. If patients continue to take such expired drugs, it will not only delay the treatment of diseases, but also produce acute (slow) toxicity and side effects, which may cause unnecessary damage to the human body.

Based on the current problem of expired family medicine storage in China and the situation that it is difficult to obtain a reference from the existing family medicine storage list [23,24], we hope to propose a new catalog of household medicine stockpile list and provide details of medicine stockpile according to the different ages, regions, and family structures of the residents in China. Therefore, we first analyzed the existing drug list to summarize the types of drugs in the family stockpile; then, we studied the specific situation of the family stockpile through interviews and questionnaires, and sorted out a set of drug lists according to the collected data to meet the actual needs; finally, our list was revised and optimized through interviews with senior doctors to obtain a list of household stockpiled drugs based on the current situation of drug use in Chinese households and to propose sub-tables that differ according to the age of the residents and the number of people living with them, as well as conditions when the household contain the old and the children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Description

The study was divided into three steps: 1. Analysis of the existing drug list: summarize the basic categories of domestic reserve drugs through case analysis; 2. Familie’s actual drug reserve research: Through the questionnaire and interview, to understand the families’ actual drug list. Then, developing a new practical home-drug system; 3. Finally, the built system was verified and reinspected according to the verification results.

2.2. Analysis of the Existing Drug List

By analyzing the classification of household drug storage by various major network platforms, we could understand the criteria and basis of their drug list classification to classify and formulate more scientific and popular drug lists.

2.2.1. Sample Selection

Four popular existing drug lists in China were selected as samples for analysis. They are: the drug list of Popular Science China, Dingxiang Doctor, PSM Pharmaceutical Shield Charity, and Xinhuanet. Then, the lists were sorted out the list. The drug information and classification, and the advantages and disadvantages of each sample are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample analysis.

2.2.2. Conclusion and the Next Step

According to the classification items of household drugs on major medical science websites, we formulated our questionnaires.

First of all, most list for cold, fever/pain relief, dermatitis, and diarrhea/diarrhea symptoms classification and give the recommended storage drugs, so in the questionnaire, we asked whether the people store the drugs, and the type of storage they used to determine the number of our drug list of all kinds of conventional drugs. At the same time, we found that the main website for drug classification is too generic, not for a specific age or region, and the number of people to put forward the classification and quantity of drugs, so the questionnaire addressed these three elements to investigate the relationship between them and the drug use and storage, so that we could formulate a more standard and scientific form.

2.3. Investigation of Actual Family Drug Reserve: Questionnaire Study and Interview Study

The second step of this work focused on families’ actual drug reserve research. Interviews and questionnaires were used to investigate families’ actual drug list.

2.3.1. Interview

Main Question Setting

A semi-structured interview was employed in this step. Based on the previous case analysis, we designed the interview questions around the obtained drugs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interview questions.

Participant Recruitment

We selected 10 interviewees from different families, ages, and regions to determine the initial direction of our questionnaire design by integrating their content.

- (1)

- Setting up

Each interviewee received an introduction email that included the interview questions list and an information sheet (the description of interview aim, method, and the use of data). The email also linked to a self-booking system where the participant could easily select their interview time.

- (2)

- Introduction

Each interview consisted of two personnel who are the interviewee and the interviewer (the researcher). The interviewer showed the information sheet and briefly summarized the interviewee’s study before the primary interview started.

- (3)

- Agreement signature

A consent form was provided, which presented eight relevant clauses about the agreement of participating in this study. Each interviewee was required to read and sign. Otherwise, the interview would not be continued.

- (4)

- The main body of the interview

The interview followed 11 questions (Table 2). Each interview was audio-recorded with each interviewee’s permission.

Data Collection and Analysis

After collecting and integrating the interview results, we summarized and integrated 10 questionnaires. By analyzing the storage and use of different drugs in various types of families, we roughly prepared our questionnaires and obtained more universal results through the questionnaire survey.

2.3.2. Questionnaire Survey

Questionnaire Design

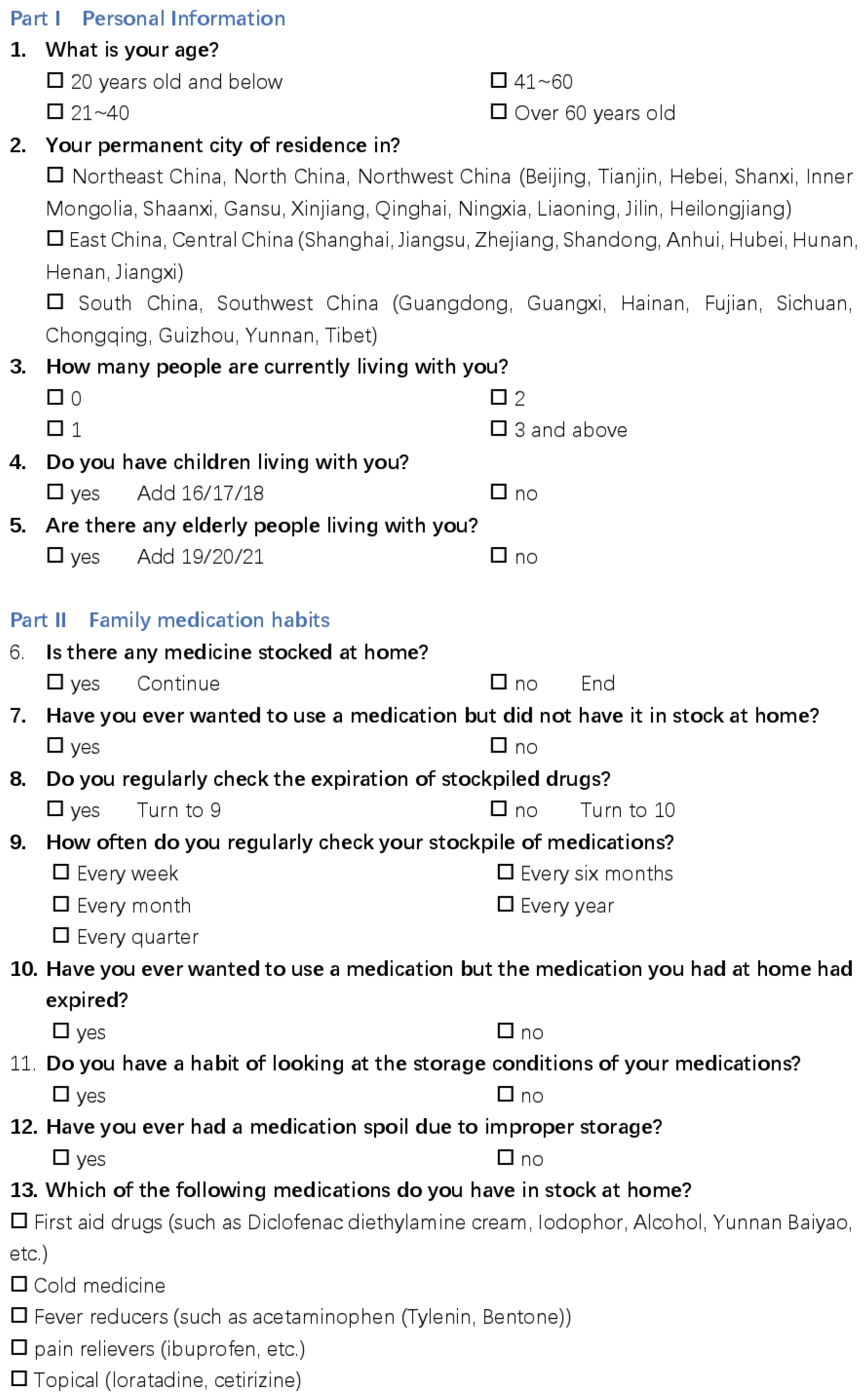

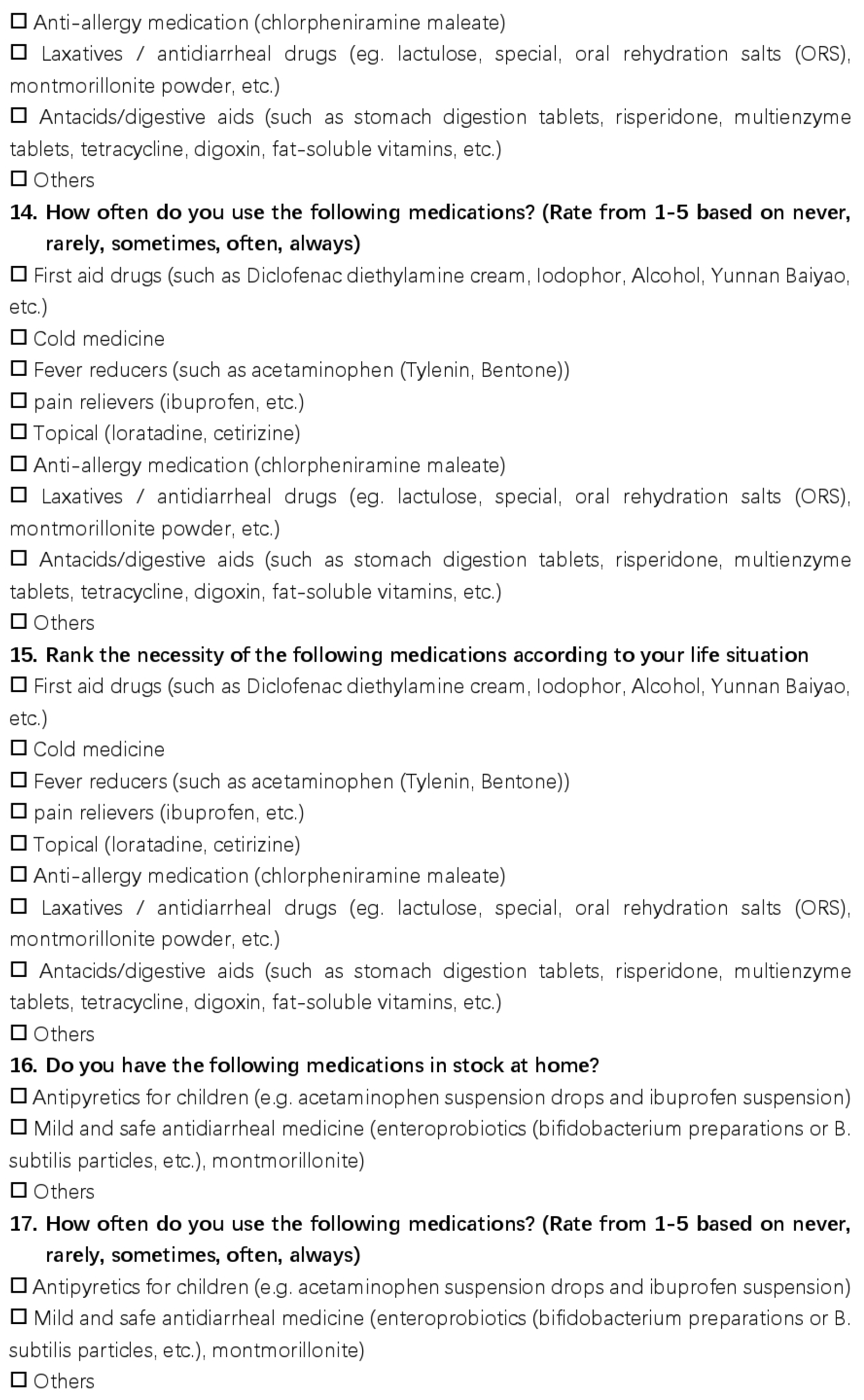

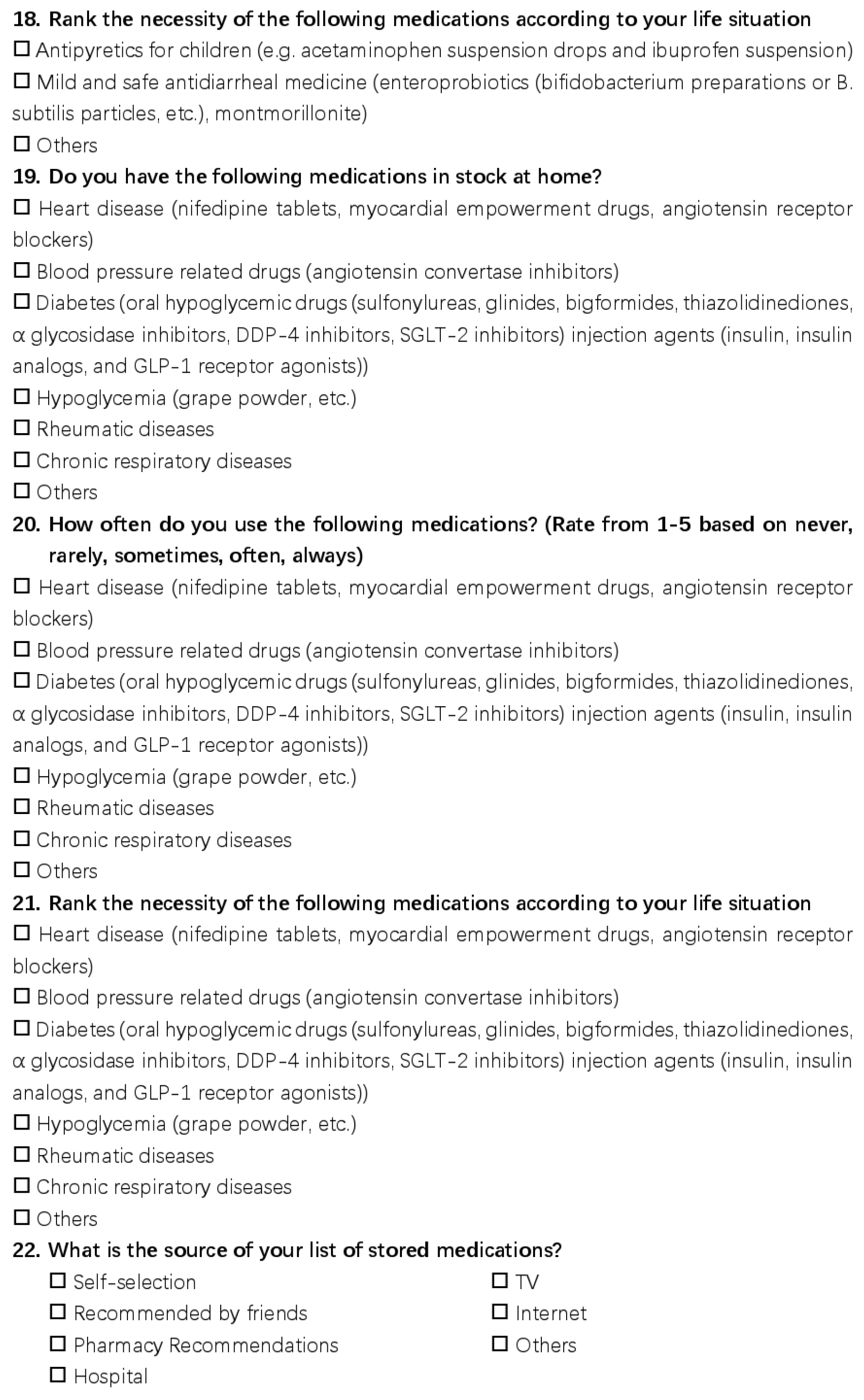

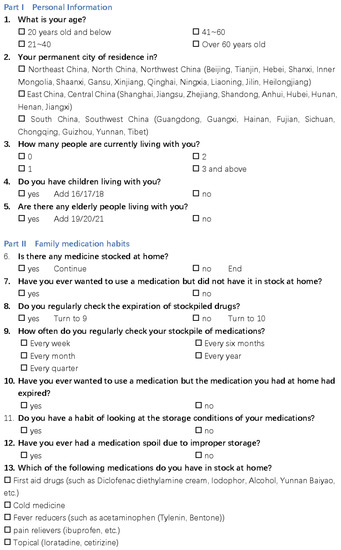

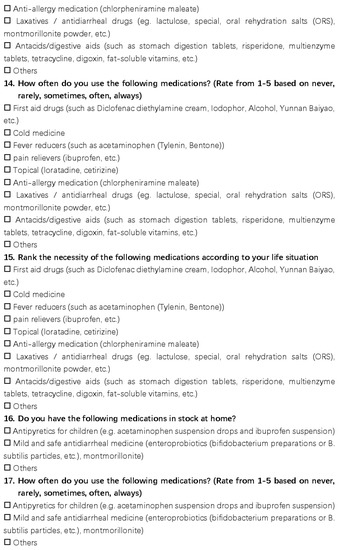

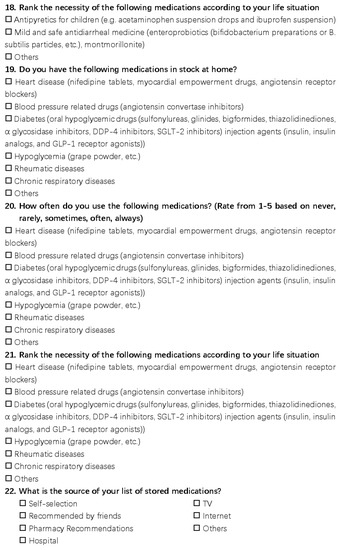

This questionnaire had a total of 21 questions and was distributed in the form of an online questionnaire, the details of which are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3. The questions asked about the basic family situation and the storage, frequency, and importance of the medications we list.

Figure 1.

The detail of the questionnaire.

Figure 2.

The detail of the questionnaire.

Figure 3.

The detail of the questionnaire.

Participant Recruitment

A total of 526 questionnaires were distributed and 526 questionnaires were collected, of which 476 were valid.

Data Collection and Analysis

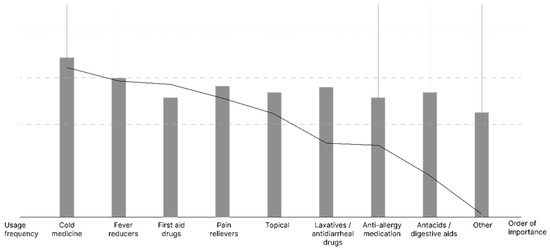

According to the data collected, we used the frequency of all kinds of drugs in the ranking; first, we recovered 476 valid questionnaire for data processing, ranking linear regression frequency and importance. Based on the importance of the drugs determined from the calculation, and in accordance with the expected results, some drugs’ frequency of use is low, indicating that people generally pay little attention to such drugs and also illustrating the importance of developing a more scientific and universal table.

3. Results

3.1. Case Study

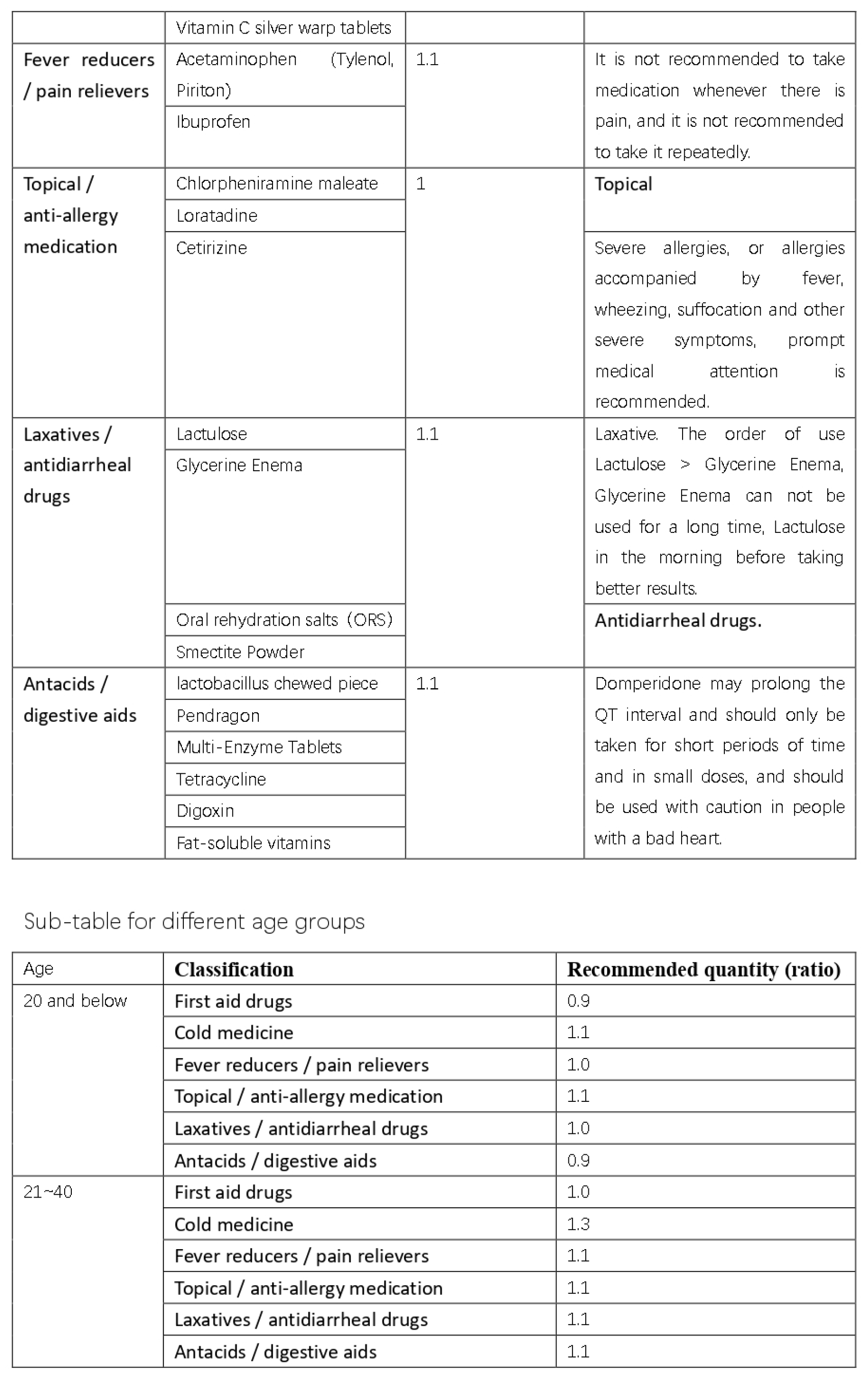

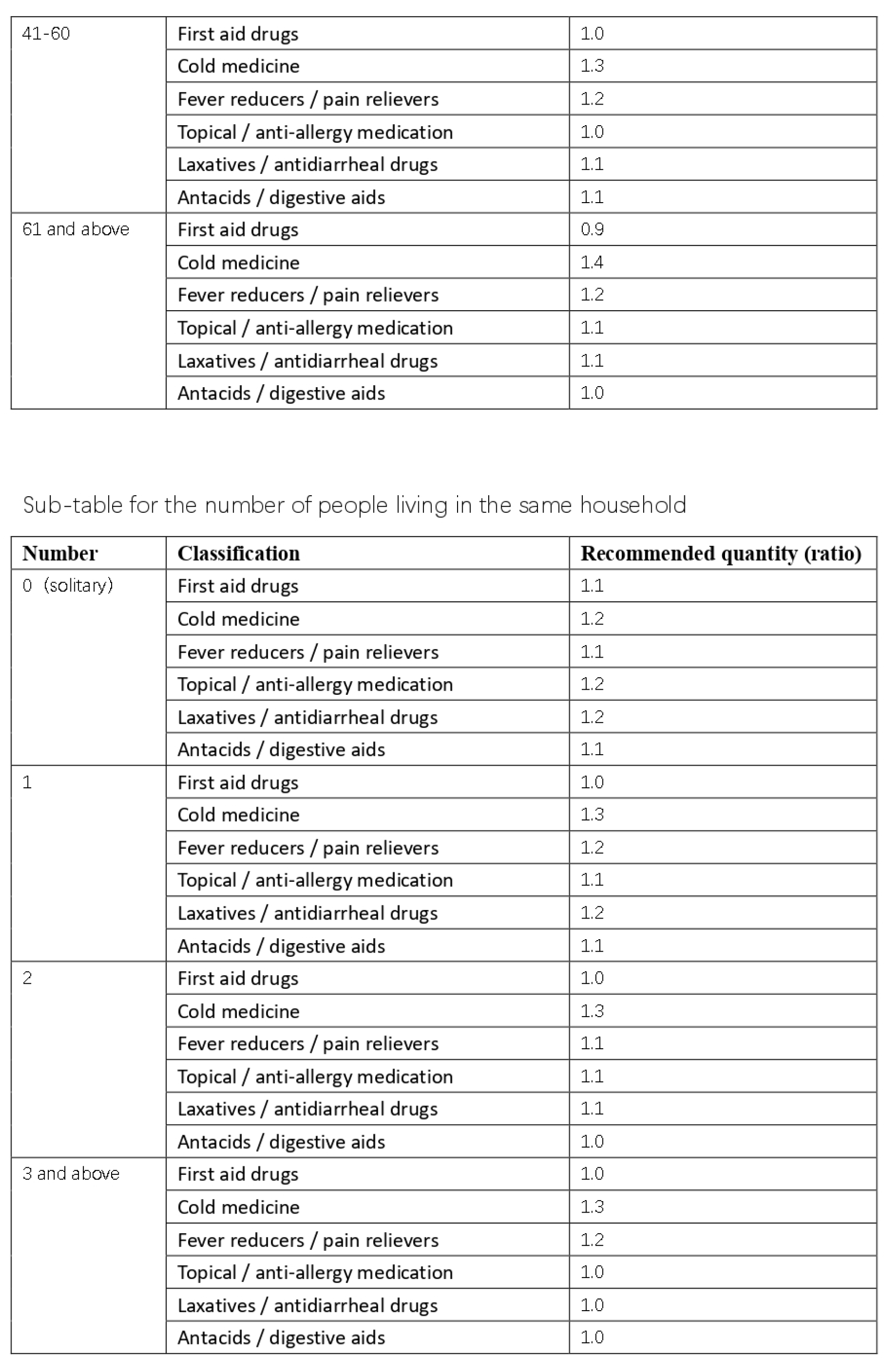

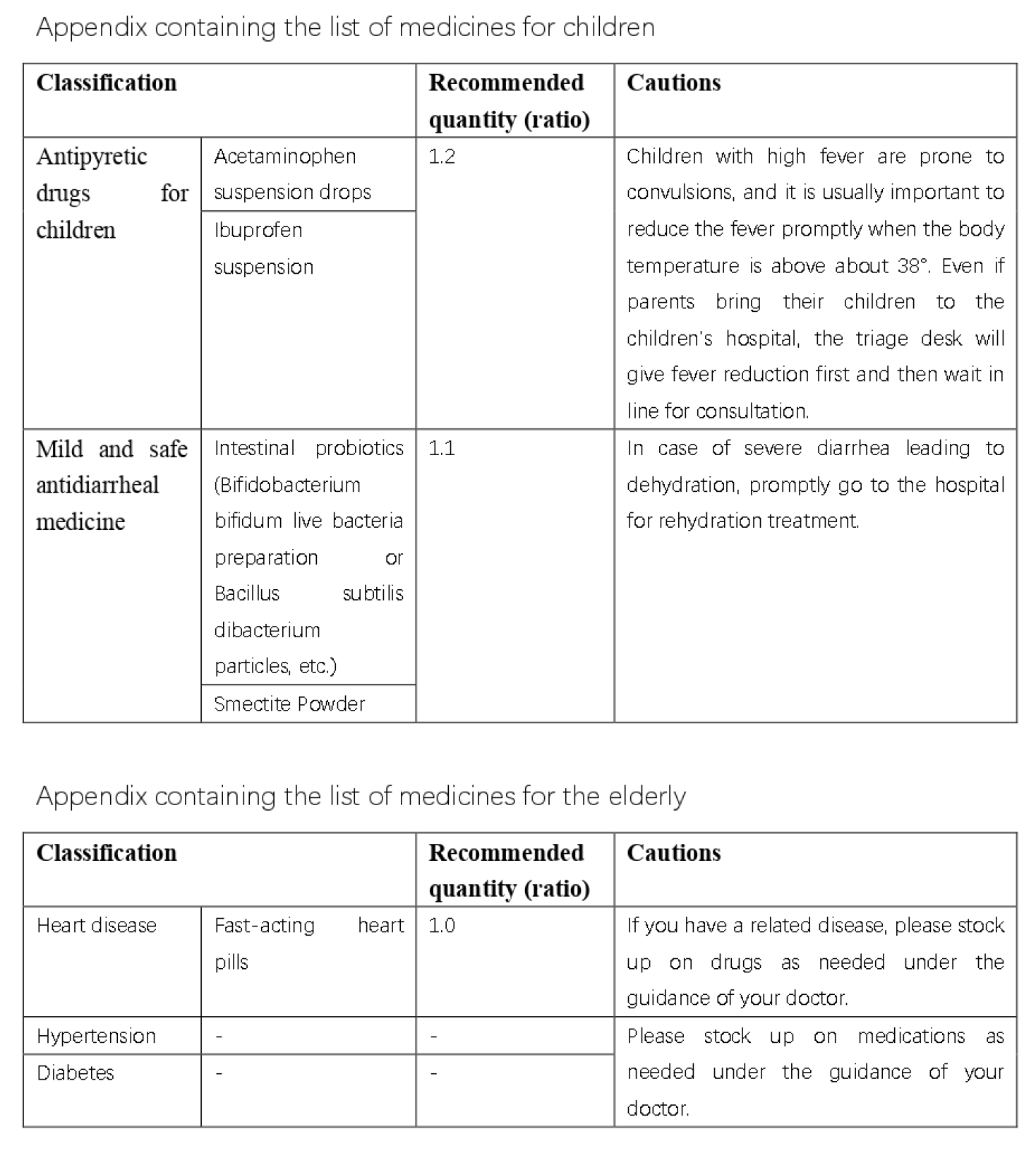

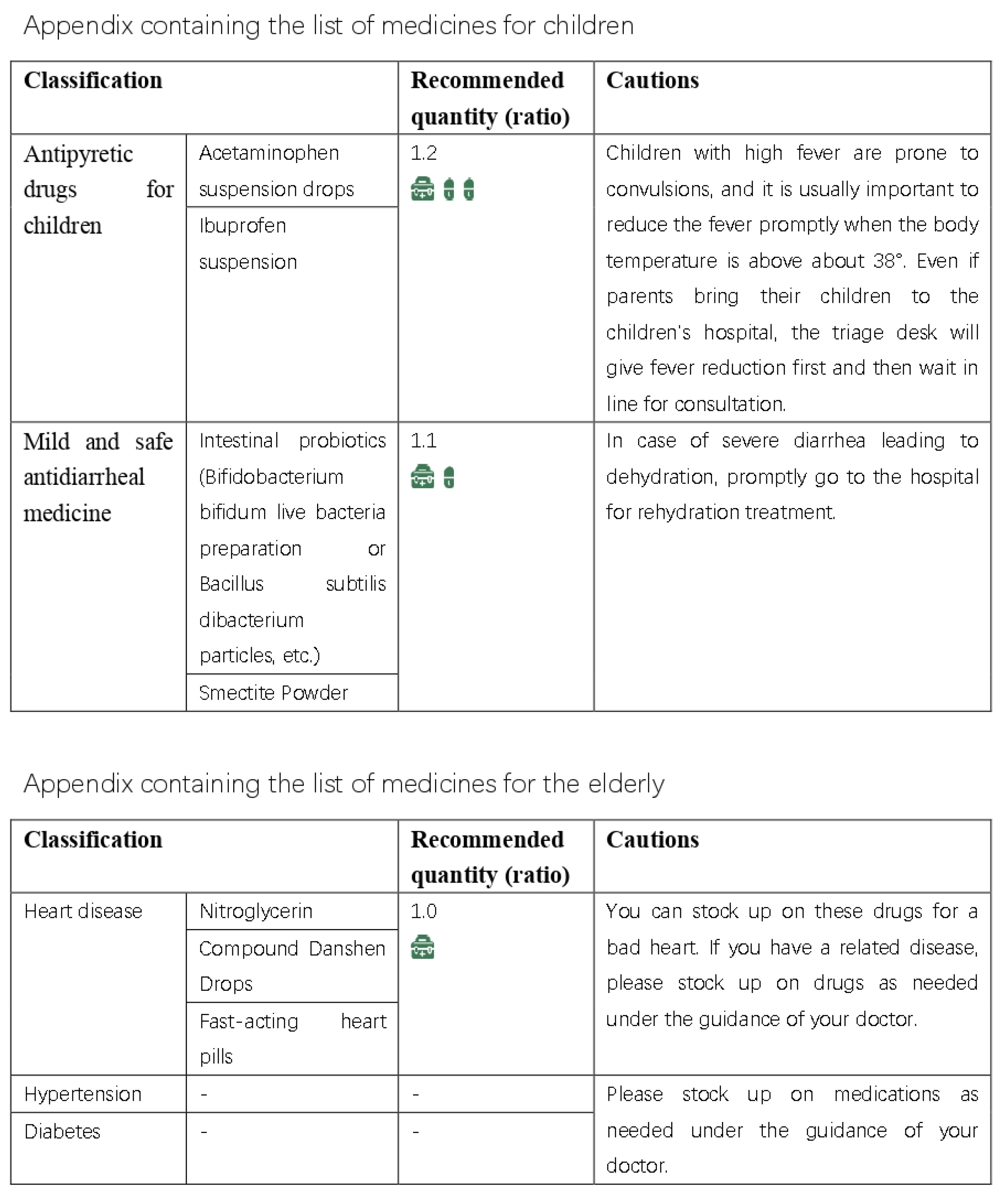

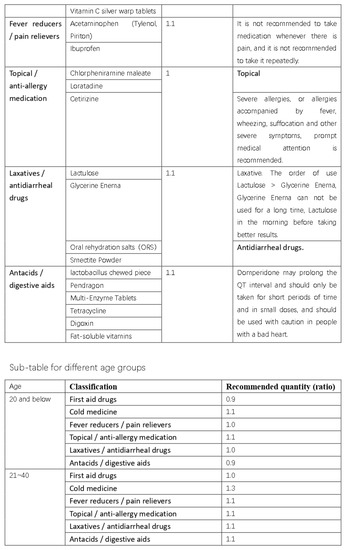

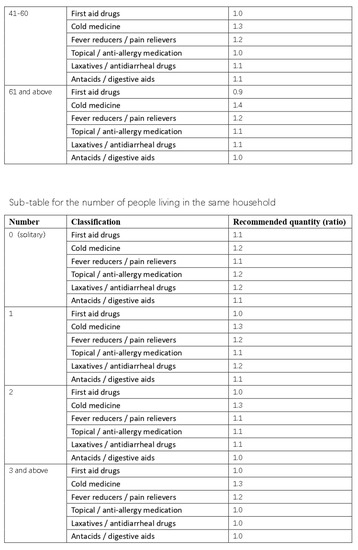

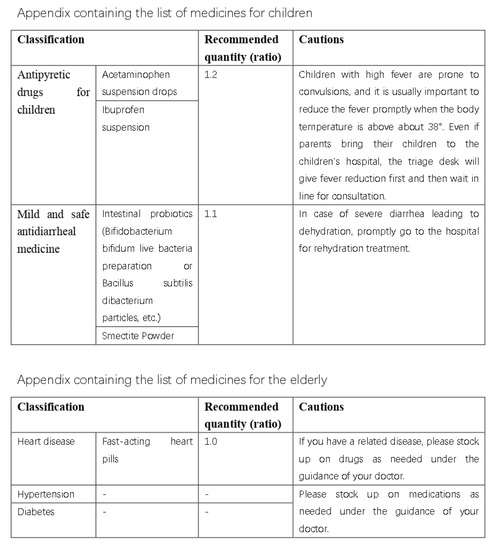

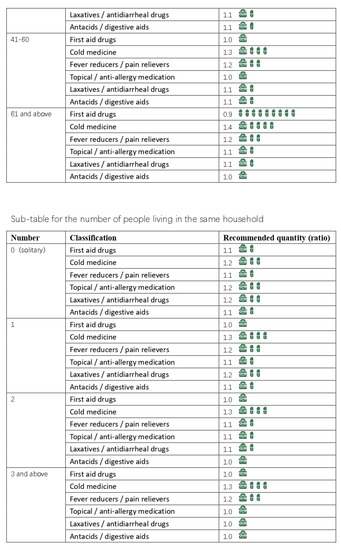

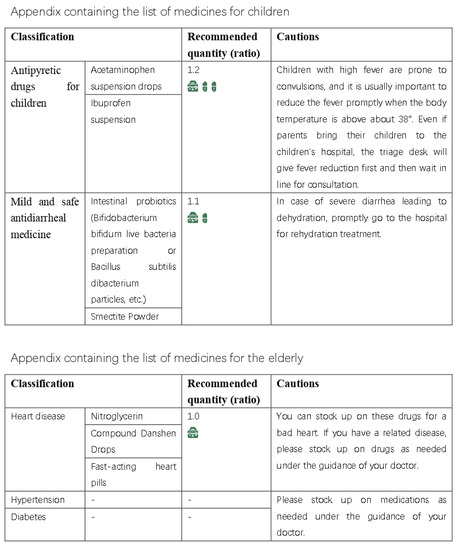

Through the analysis of different lists, based on the method of forming hospital drug lists, we summarized the types of drugs that are stocked at home in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 3.

General family stockpile of drugs list.

Table 4.

List of supplemental stockpile drugs for families with children.

Table 5.

List of supplemental stockpile drugs for families with elderly members.

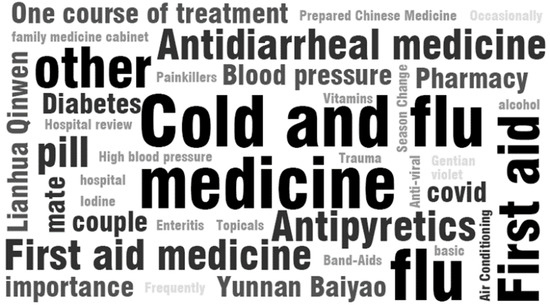

3.2. Interview

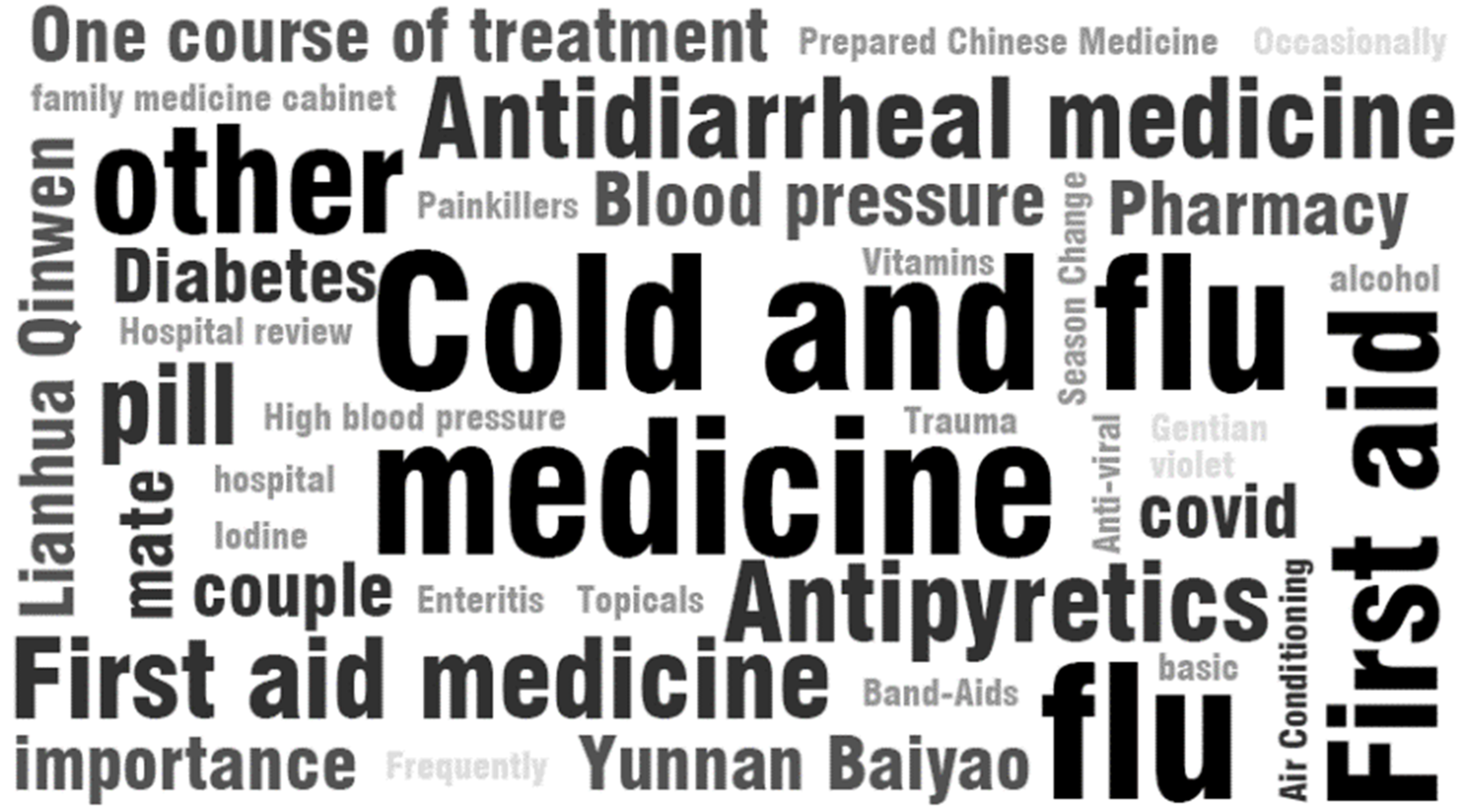

We found that many families were in the situation of “wanting to use a certain medicine but the medicine stocked at home has expired” through the interviews and research. The word cloud based on the interview content is shown in Figure 4, and the content analysis is shown in Table 6. According to Figure 4, the frequency with which respondents mentioned these elements broadly demonstrates the importance of these medicines to a family.

Figure 4.

Word cloud generated based on interview results.

Table 6.

Summary and analysis of user interview results.

3.3. Questionnaire

A total of 526 questionnaires were distributed, and 476 valid questionnaires were collected.

3.3.1. Data Summaries

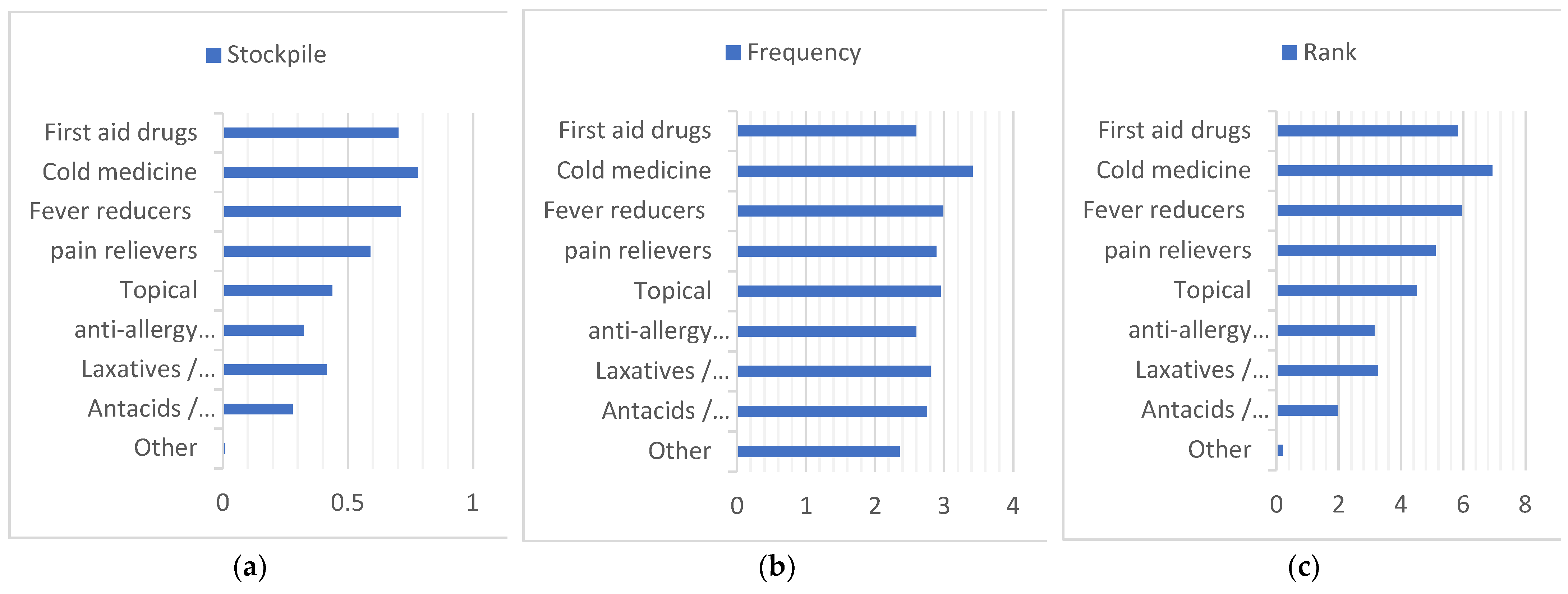

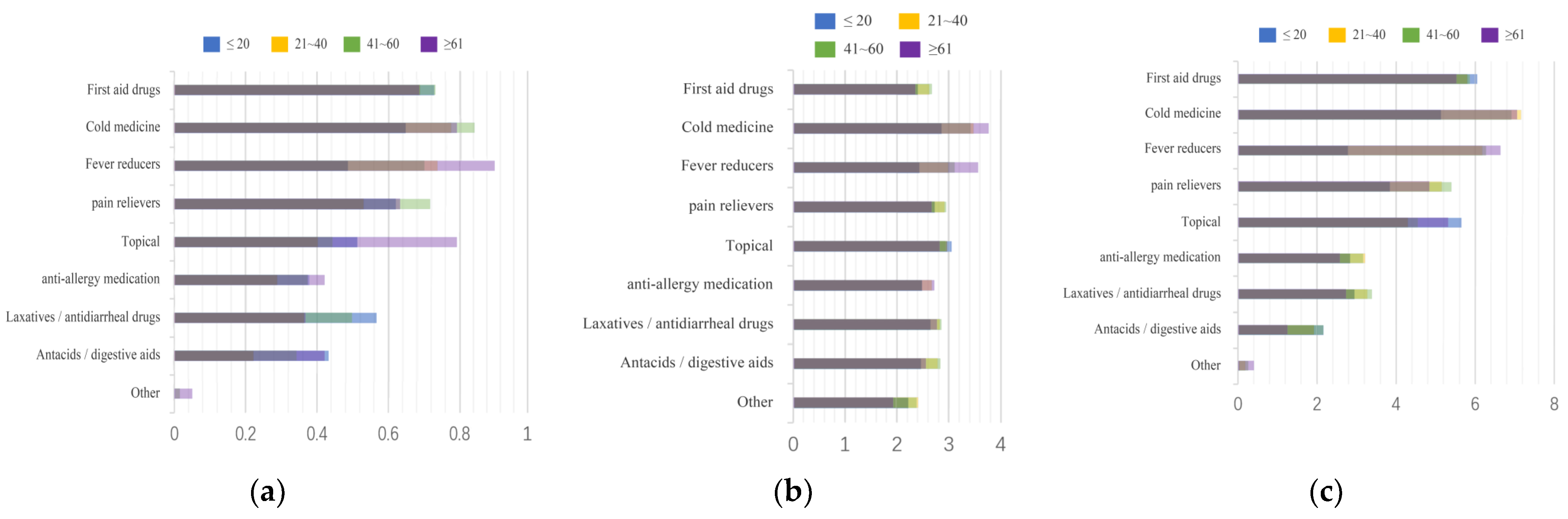

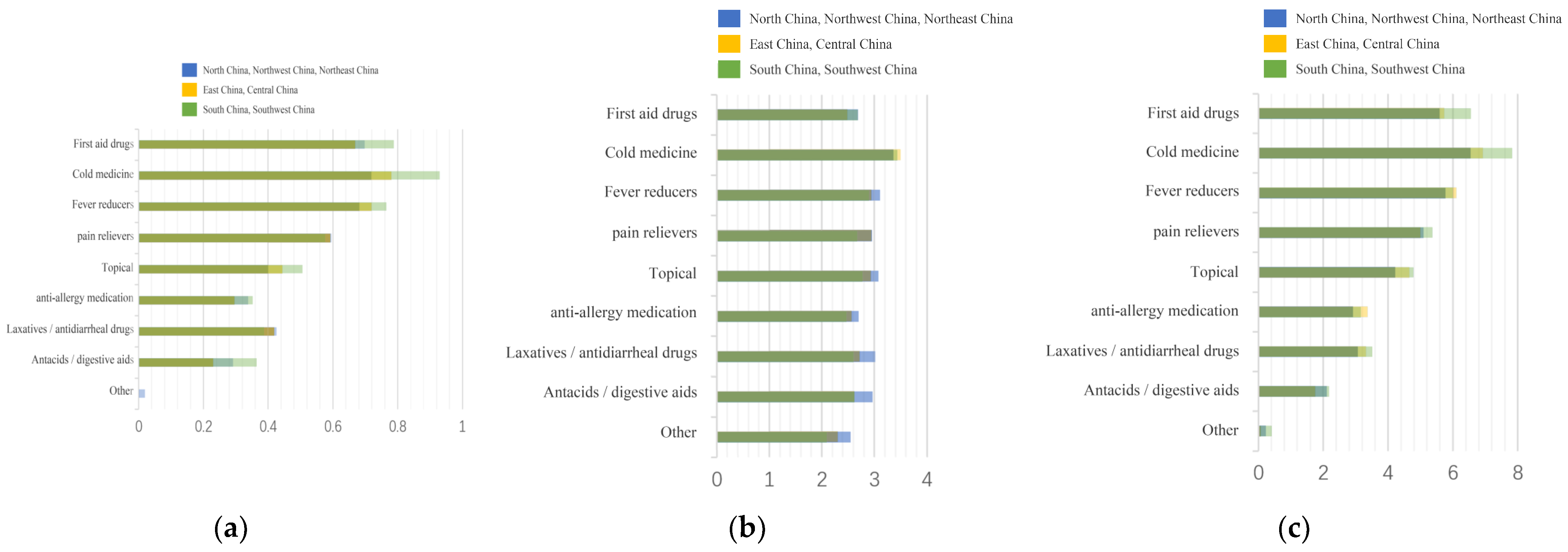

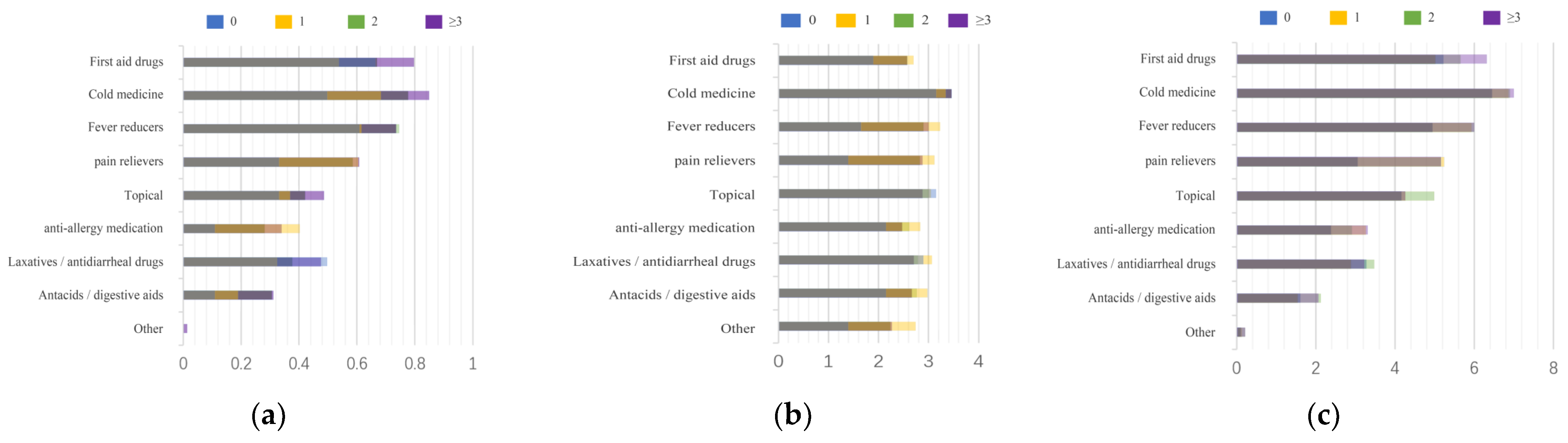

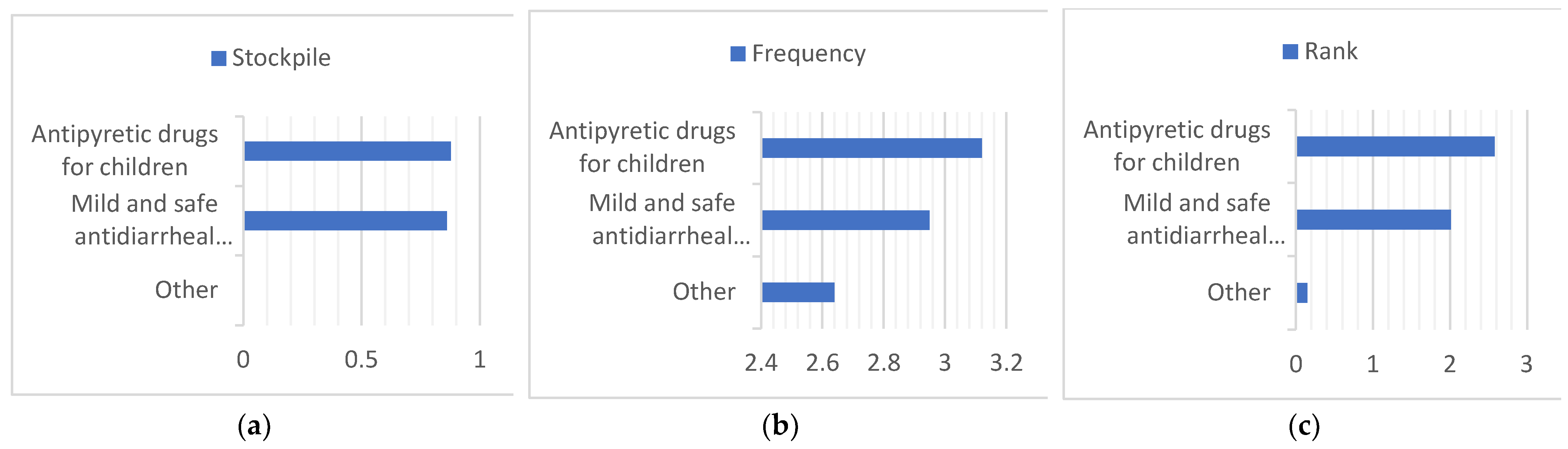

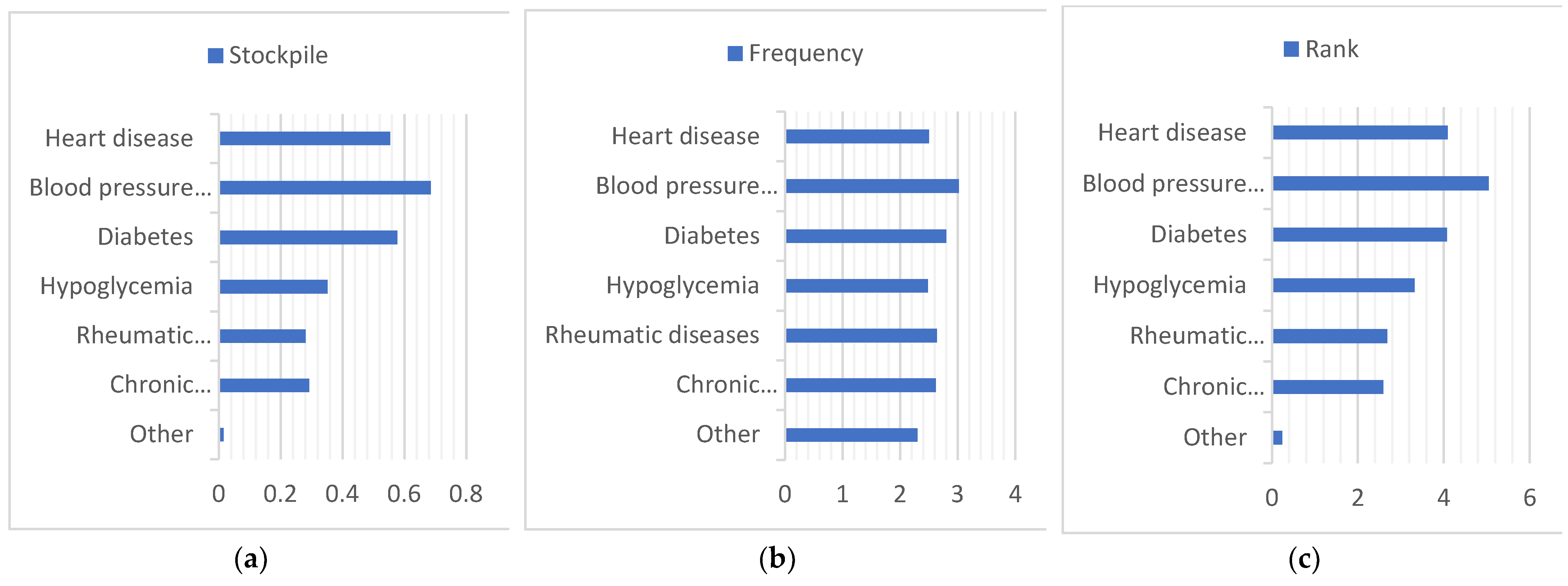

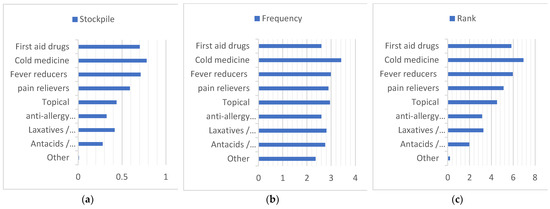

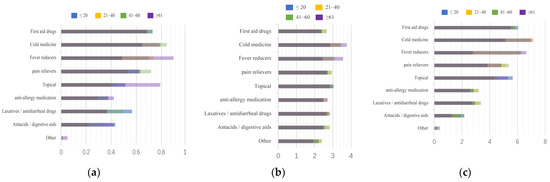

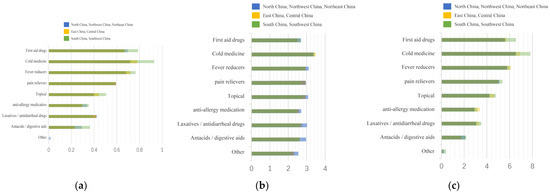

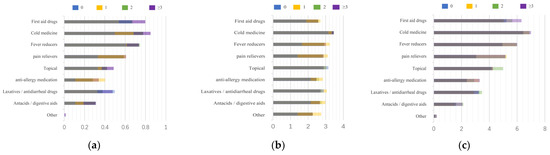

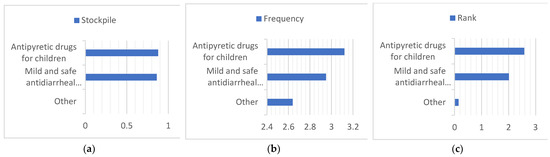

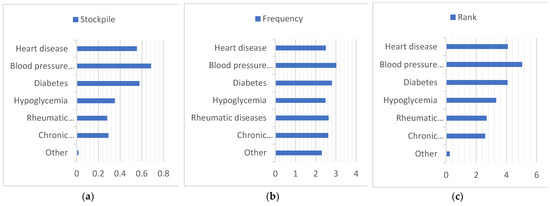

First, we summarize all the data in Figure 5, and to facilitate the comparison of different regions, ages, and cohabitants, we stacked the data obtained on a graph in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. Households with children and households with elderly members are listed separately, as in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 5.

Summary of the overall drug stockpile, frequency of drug use, and ranking of drug importance. (a) Stockpile, (b) Frequency, (c) Rank.

Figure 6.

Summary of drug stockpiling, frequency of drug use, and ranking of drug importance by age. (a) Stockpile, (b) Frequency, (c) Rank.

Figure 7.

Summary of drug stockpiles, frequency of drug use, and ranking of drug importance in different regions. (a) Stockpile, (b) Frequency, (c) Rank.

Figure 8.

Summary of drug stockpiling, frequency of drug use, and ranking of drug importance for different number of people living together. (a) Stockpile, (b) Frequency, (c) Rank.

Figure 9.

Summary of the child-specific medication stockpile, frequency of medication use, and ranking of medication importance for the child’s family. (a) Stockpile, (b) Frequency, (c) Rank.

Figure 10.

Summary of medication stockpiling, frequency of medication use, and ranking of importance of medication for elderly households with elderly members. (a) Stockpile, (b) Frequency, (c) Rank.

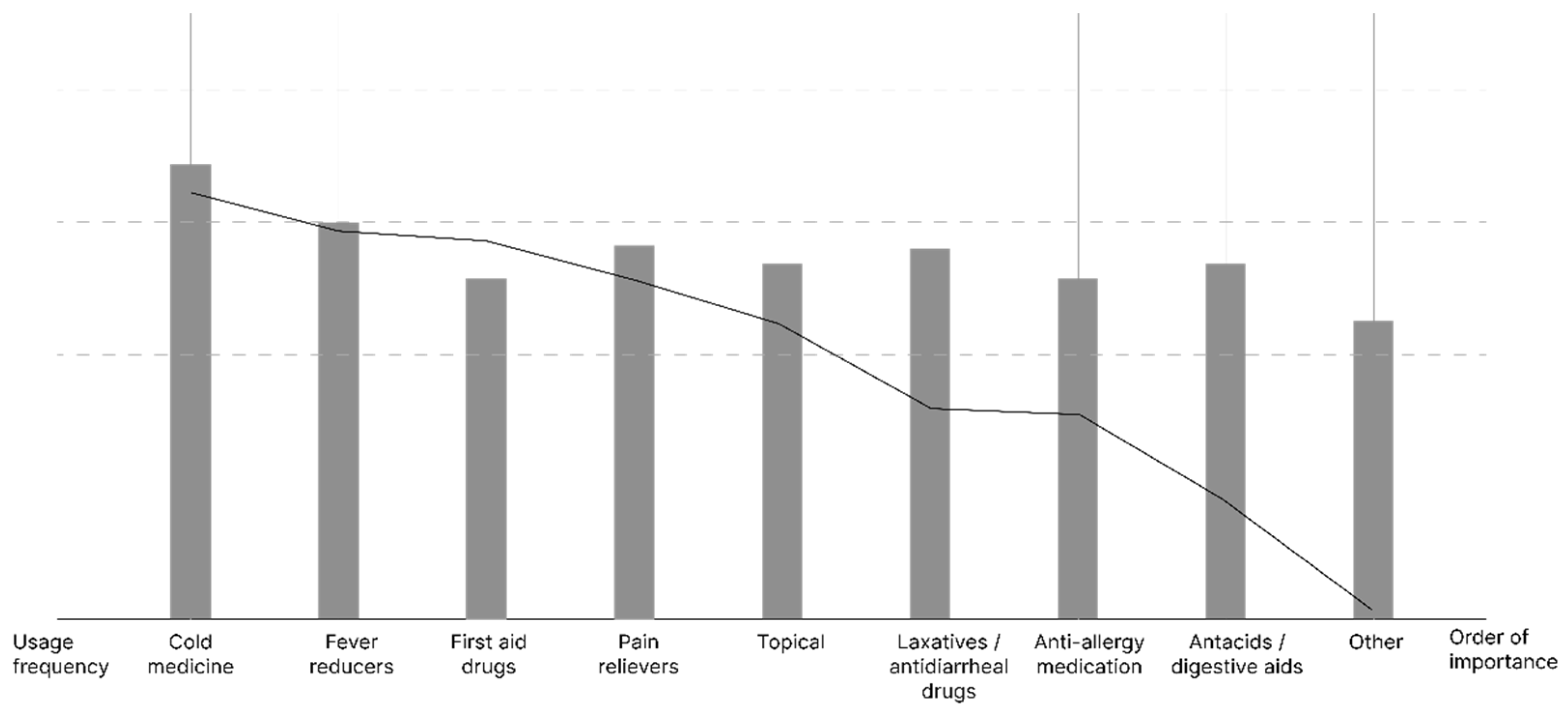

3.3.2. Data Regression Processing

As Table 7 and Table 8 show that, the value of 1.788 is slightly less than 2.0, which is slightly correlated but does not affect it. R2 = 0.572: The ranking of people’s importance of medicines can affect 57.2% of people’s frequency of using medicines, which means that establishing the correct concept of the importance of medicines can improve people’s scientific perception of the storage and use of medicines to a certain extent.

Table 7.

Model Summary a.

Table 8.

Coefficient a.

Significance 0.018 > 0.005 so people’s ranking of the degree of drug use cannot significantly impress the frequency of drug use, and the impression coefficient is 0.105 for a positive, positive impression.

From the analysis results (Figure 11), it can be seen that there is no significant linear relationship between the frequency of use and the ranking of the importance of drugs, and it can be known that most households do not pay much attention to the understanding of various types of drugs, which may lead to unreasonable and irregular storage methods and stockpiles of drugs.

Figure 11.

Frequency and importance of different types of drugs correlation analysis chart.

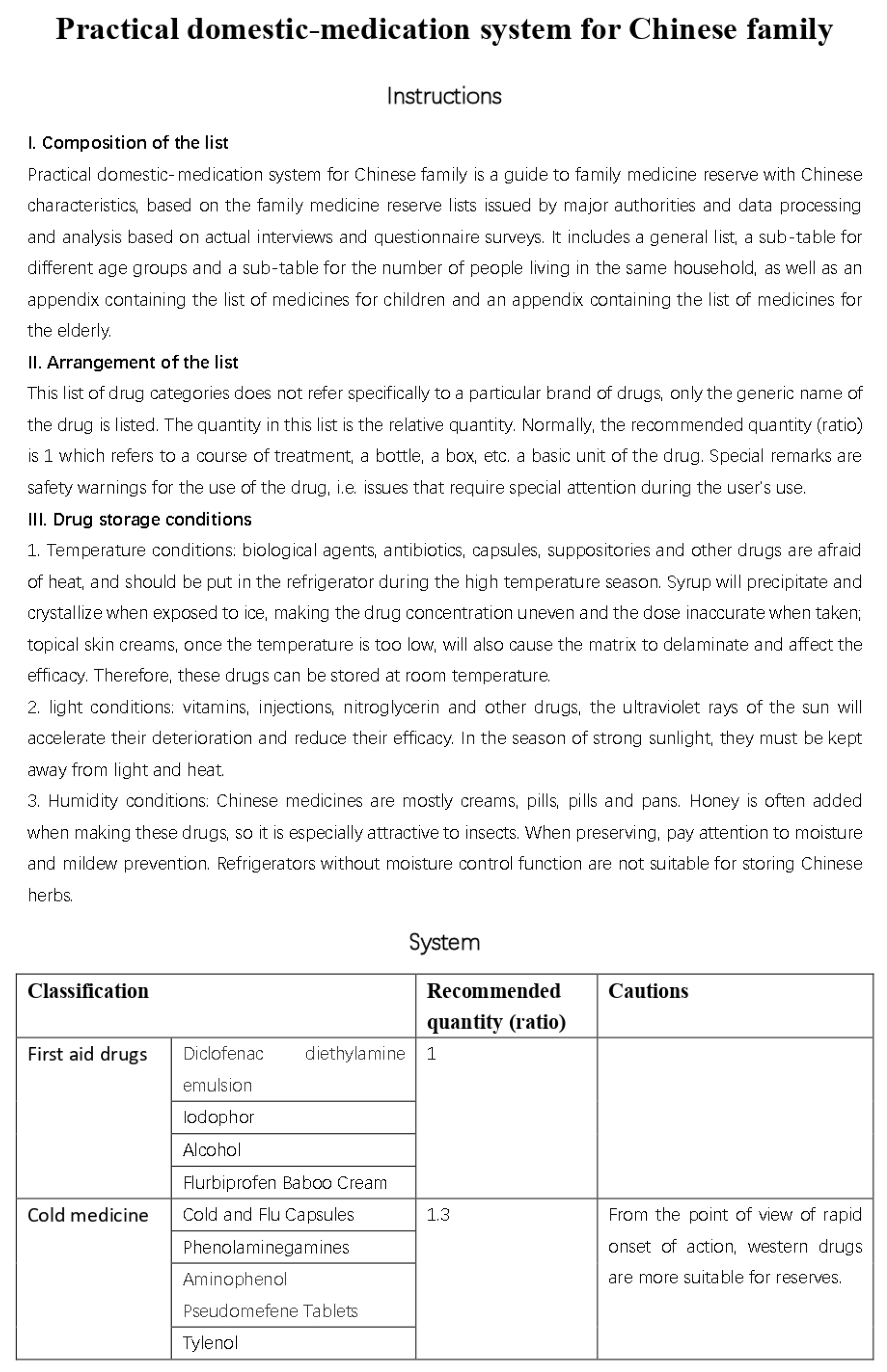

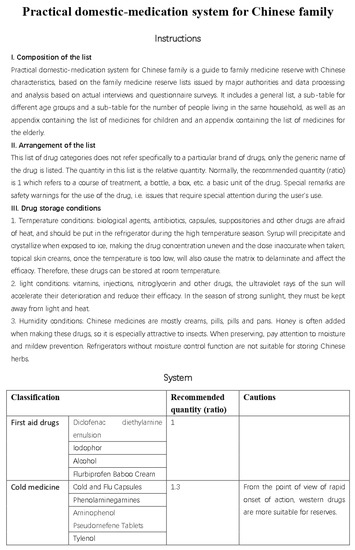

3.4. Preliminary Establishment of a Domestic-Medication System

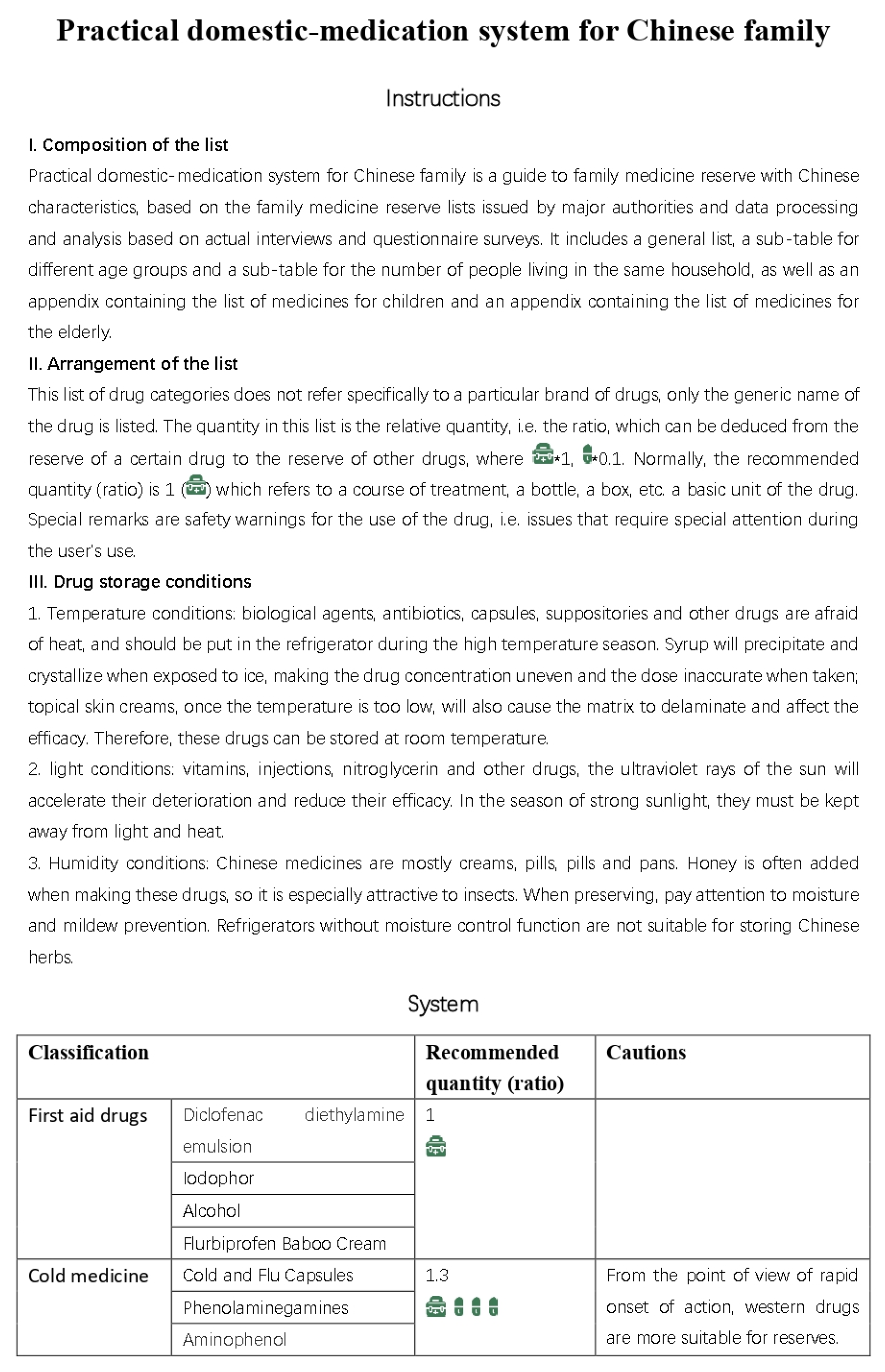

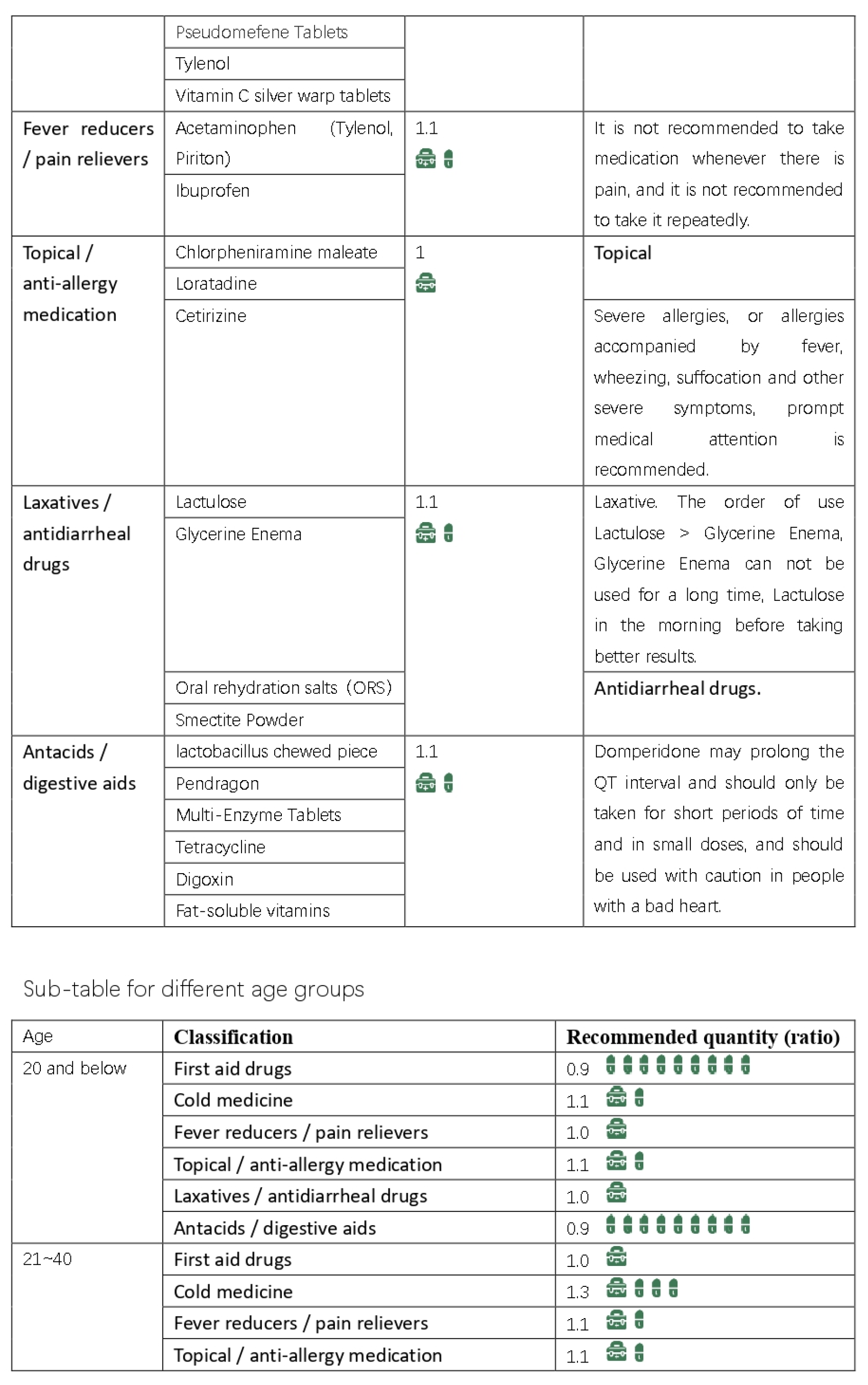

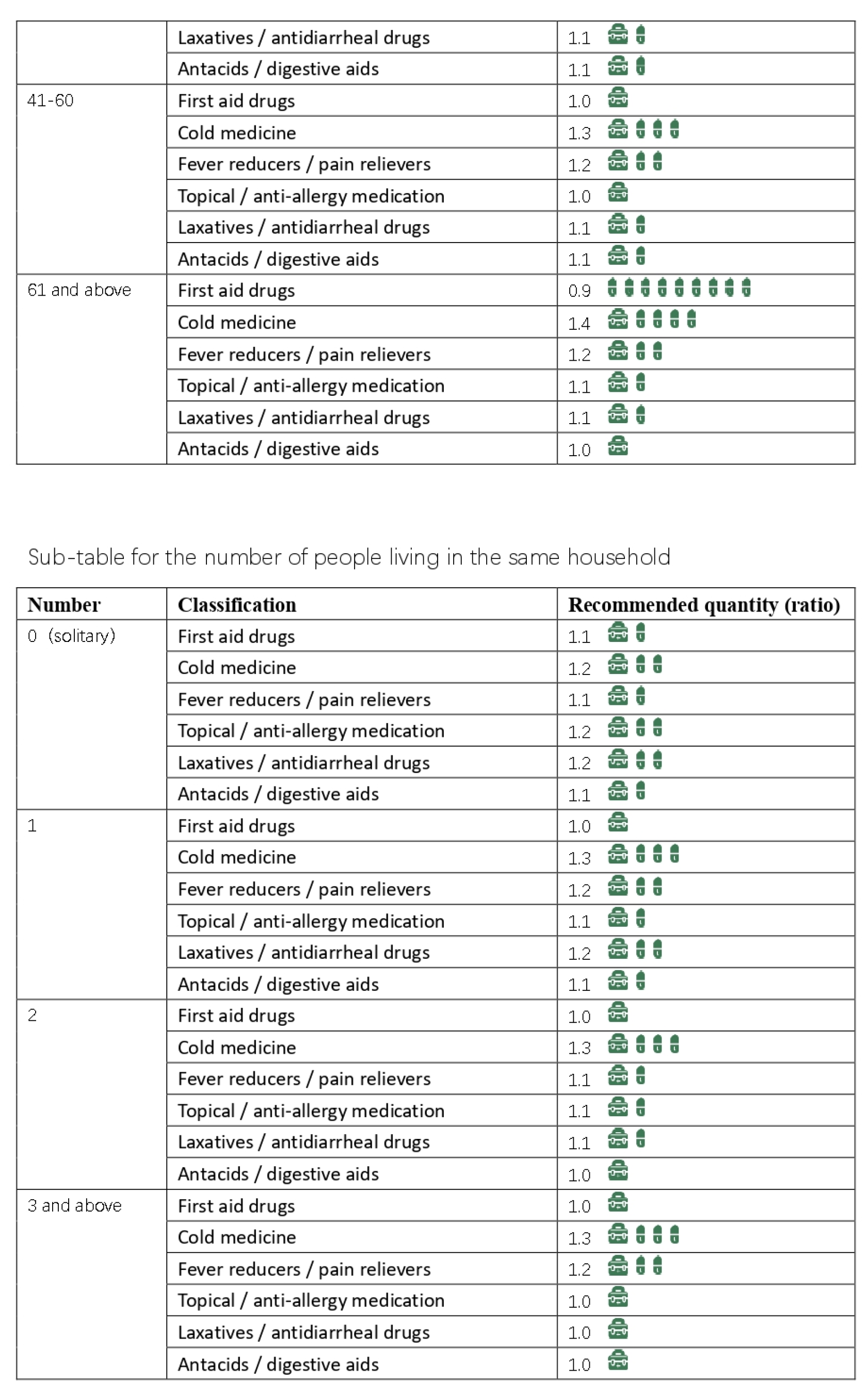

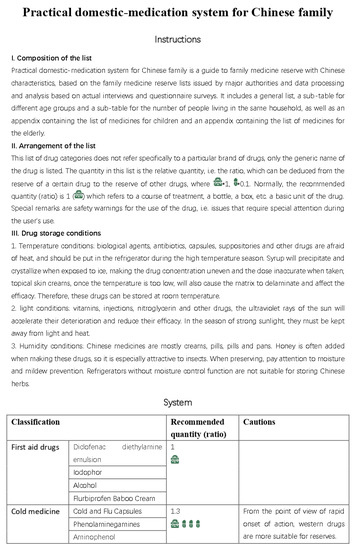

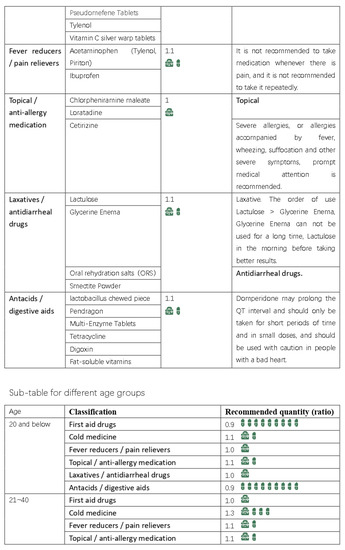

Based on the results of our interviews and questionnaire research, we initially developed a practical domestic-medication system for the Chinese family, as shown in Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 12.

The initial version of the system.

Figure 13.

The initial version of the system.

Figure 14.

The initial version of the system.

Figure 15.

The initial version of the system.

4. Validation and Iteration of Study Results

4.1. Verification Method: Interview with Senior Doctors

We obtained the effective questionnaire information integration, our form, which is divided into the general table and points table, general table for various situations of families that have applicability, and a schedule for different ages according to the number of families to supplement drug storage recommendations. Moreover, according to the recycling questionnaire, different areas of family use drugs in type and use frequency show no significant difference, so were not taken into account when sorting.

4.1.1. Sample Selection

Based on our initial system, we sought out four senior physicians to evaluate it.

4.1.2. Problem Setting

Finally, the following types of questions should change flexibly according to the doctor’s answer, such as which questions the doctor thinks has more reference value within the list.

4.1.3. Participants

Four senior physicians with clinical experience were contacted as respondents.

- (1)

- Setting up

Each interviewee received an introduction email that included the interview questions list and an information sheet (the description of interview aim, method, and the use of data). The email also linked to a self-booking system where the participant could easily select their interview time.

- (2)

- Introduction

Each interview consisted of two personnel who are the interviewee and the interviewer (the researcher). The interviewer showed the information sheet and briefly summarized the interviewee’s study before the primary interview started.

- (3)

- Agreement signature

A consent form was provided that presented eight relevant clauses about the agreement of participating in this study. Each interviewee was required to read and sign. Otherwise, the interview would not be continued.

- (4)

- The main body of the interview

The interview followed four questions (Table 9). Each interview was audio-recorded with each interviewee’s permission.

Table 9.

Interview questions.

4.1.4. Data Collection and Analysis

We sorted and analyzed the doctors’ answers. (Table 10).

Table 10.

Doctors’ answers.

4.2. Validation Results

Based on the interview results of the interviewed doctors, our list became more practical and improved.

4.3. Optimize Iterations

In the validation part, the doctors suggested using amoxicillin, cephalosporin, and erythromycin to replace the acid drugs in tetracycline. Moreover, for the treatment of heart failure drugs, it was suggested that it is better to use nitroglycerin or compound Dans hen drop pill, a quick effect save heart pill. Based on these suggestions, we adjusted the content of our list.

4.4. Final Results

Here are the final results, are shown in Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 (Supplementary File S1).

Figure 16.

Final practical domestic-medication system.

Figure 17.

Final practical domestic-medication system.

Figure 18.

Final practical domestic-medication system.

Figure 19.

Final practical domestic-medication system.

Figure 20.

Final practical domestic-medication system.

5. Discussion and Summary

In this paper, we focused on Chinese households’ stockpile of medicines. Based on the initial list of medicines, we determined the relationship between the number of different types of medicines and the relationship between the perceived importance of medicines and the frequency of using medicines through interviews and questionnaires and gradually improved the stockpile of medicines in Chinese households. Based on this, we established a standardized, systematic, and scientific system of household medicine stockpiling, which increased the connection between the type and quantity of medicine stockpile and actual life, reduced the misuse and waste of medicine caused by the expiration of medicine, and finally obtained the approval of doctors.

Due to the lack of attention to scientific stockpiling of medications, most respondents did not have a clear plan of stockpiling medications at home and lacked a general understanding, especially of the amount of stockpiling of different medications. Moreover, we found that people of different ages living together influenced the stockpiling of drugs, frequency of drug use, and perceived importance of drugs, but different regional factors had almost no influence on these issues. However, there is no correlation between the frequency of drug use and the importance of drugs, and there is a difference in the perception of drug stockpiling, with the actual frequency of use of drugs they consider important being low and the actual frequency of use of drugs they consider unimportant being high. All four senior doctors agreed with the existing problems we raised and the list we proposed and added to it, and finally, we formed a relatively complete list.

The innovation of our research results this time is to propose the relative stockpile amount of each kind of medicine in the process of household stockpiling. When a resident is familiar with the stockpile of a certain drug, they can quickly deduce the stockpile of other unfamiliar drugs through this list according to their age and family situation. This study makes the household stockpile list more relevant and can provide some reference for the general population to stockpile drugs so that the list can realistically solve the problems about the type and quantity of drugs stockpiled by residents in different living environments. It also helps families to stock a reasonable amount of medicines, thus reducing the risk of expired medicines being consumed by family members and the impact of expired medicines on the environment.

Limitations

This system is only for the basic situation of Chinese residents, and it is our preliminary research on this issue. At the same time, we hope to conduct a study on the household stockpile in other regions in the future so that we can conclude a universal list of drugs worldwide.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph20021060/s1, File S1: Final result_Practical Domestic-medication System for Chinese family.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and C.G.; data curation, C.X. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, C.X. and Y.Z.; project administration, C.X. and Y.Z.; Supervision, Y.C.; writing—original draft, Y.C., C.X. and Y.Z.; writing—review & editing, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Beijing Institute of Technology Research Fund Program for Young Scholars: 3250012222201.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jiang, Y.; Bao, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Xu, Y. Analysis of Take-back Situation of Expired Pharmaceuticals Based on the Empirical Investigation of Pharmaceuticals from House-hold Reserves and Its Disposal. Pharmacy Today 2019, 29, 765–768. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S. Family medicine box is also best to change with the season. World Labor. Secur. 2019, 28, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Kong, J.; Zhou, S. Discussion on the establishment of China’s expired drug disposal system. J. Lib. Army Pharm. 2015, 31, 372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Zang, W. Analysis of the perceived attitudes of Chinese household residents towards the recycling and disposal methods of expired drugs-A case study of Changchun City. Ind. Technol. Forum 2020, 19, 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Survey on residents’ disposal behavior of expired drugs in Chongqing households and suggestions for recycling. China Pharm. 2018, 29, 999–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee. The future of family medicine: A collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2 (Suppl. 1), S3–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakel, R.E. Textbook of Family Medicine E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nutting, P.A.; Miller, W.L.; Crabtree, B.F.; Jaen, C.R.; Stewart, E.E.; Stange, K.C. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009, 7, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, J.L.; Donatelle, E.P.; Thomas, A., Jr.; Scherger, J.E.; Taylor, R.B. (Eds.) Family Medicine: Principles and Practice; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L. Family emergency medicine stockpile list. Love Marriage Fam. (Mon. End) 2022, 2, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu, R.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Cain, K.L.; Chapman, J.E.; King, A.C. Age differences in the relation of perceived neighborhood environment to walking. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2009, 41, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Birnbaum, H.; Bromet, E.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.; Shahly, V. Age differences in major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, C.; Vaartjes, I.; Heintjes, E.M.; Spiering, W.; van Dis, I.; Herings, R.M.; Bots, M.L. Persisting gender differences and attenuating age differences in cardiovascular drug use for prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease, 1998–2010. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 3198–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peregoy, J.A.; Clarke, T.C.; Jones, L.I.; Stussman, B.J.; Nahin, R.L. Regional variation in the use of complementary health approaches by US adults. NCHS Data Brief 2014, 146, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Bellantuono, C.; Fiorio, R.; Tansella, M. Psychotropic drug use in Italy: National trends and regional differences. Psychol. Med. 1986, 16, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Stanley, L.R.; Beauvais, F. Regional differences in drug use rates among American Indian youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 126, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, B.K.; Braverman, J. Family structure differences in health care utilization among US children. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemovich, V.; Lac, A.; Crano, W.D. Understanding early-onset drug and alcohol outcomes among youth: The role of family structure, social factors, and interpersonal perceptions of use. Psychol. Health Med. 2011, 16, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. The family and family structure classification redefined for the current times. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2013, 2, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astin, J.A.; Marie, A.; Pelletier, K.R.; Hansen, E.; Haskell, W.L. A review of the incorporation of complementary and alternative medicine by mainstream physicians. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E.; White, A. The BBC survey of complementary medicine use in the UK. Complement. Ther. Med. 2000, 8, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Huss, R.; Summers, R.; Wiedenmayer, K. Managing Pharmaceuticals in International Health; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon, J.T.; Fillenbaum, G.G.; Schmader, K.E.; Kuchibhatla, M.; Horner, R.D. Inappropriate drug use among community-dwelling elderly. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2000, 20, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurwitz, J.H.; Rochon, P. Considerations in designing an ideal medication-use system: Lessons from caring for the elderly. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2000, 57, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).