Protective and Overprotective Behaviors against COVID-19 Outbreak: Media Impact and Mediating Roles of Institutional Trust and Anxiety

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Relationship between Pandemic-Related Media Use, Protective Behavior, and Overprotective Behavior

1.3. The Mediational Role of Institutional Trust between Pandemic-Related Media Use and Health-Related Behaviors

1.4. The Mediational Role of Anxiety between Pandemic-Related Media Use and Health-Related Behavior

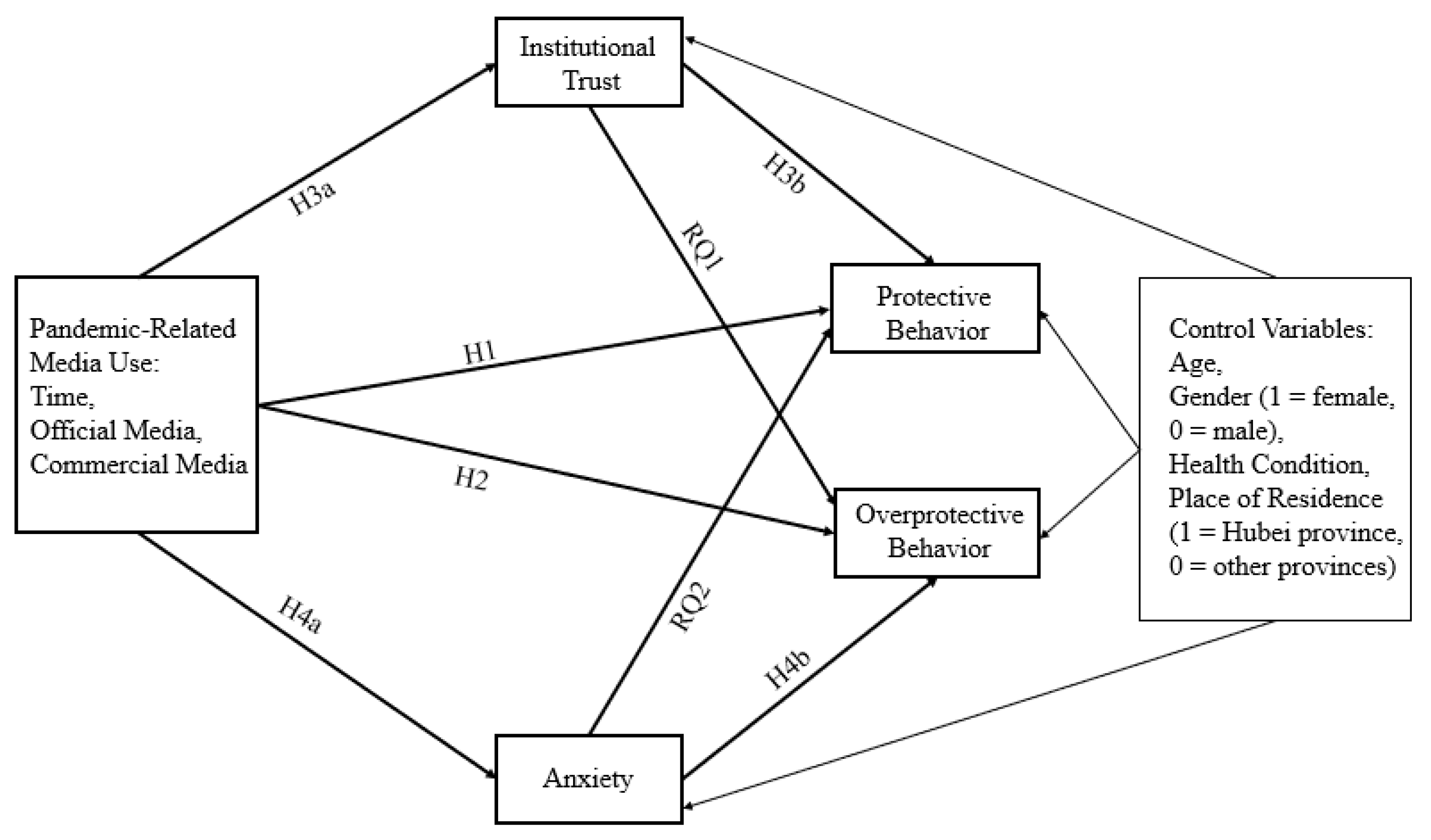

1.5. Research Conceptual Model

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Pandemic-Related Media Use

2.3.2. Protective Behavior

2.3.3. Overprotective Behavior

2.3.4. Anxiety

2.3.5. Institutional Trust

2.4. Data Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Structural Equation Modeling Predicting Protective and Overprotective Behaviors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebrahim, S.H.; Ahmed, Q.A.; Gozzer, E.; Schlagenhauf, P.; Memish, Z.A. COVID-19 and community mitigation strategies in a pandemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: Schools set to close across UK except for children of health and social care workers. BMJ 2020, 368, m1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adalja, A.A.; Toner, E.; Inglesby, T.V. Priorities for the US health community responding to COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 14, 1343–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.H.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.Q.; Ren, R.Q.; Leung, K.S.M.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 13, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020, 13, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.M.; Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Barnighausen, T. COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. Lancet 2020, 395, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahebao. A Funeral Parlour in Wuhan Is Full of Landless Mobile Phones? False! Available online: https://www.dahebao.cn/news/1498074?cid=1498074 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Ye, Y.S.; Wang, R.X.; Feng, D.; Wu, R.J.; Li, Z.F.; Long, C.X.; Feng, Z.C.; Tang, S.F. The recommended and excessive preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A community-based online survey in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baijiahao. I Was Driven Crazy by My Mother: An Aunt in Hangzhou Washed Dozens of Times a Day for Epidemic Prevention, and Forced Her Family to Wash Their Hands Together. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1707311481656139927&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- French, I.; Lyne, J. Acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms precipitated by media reports of COVID-19. Irish J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.; Schnall, A.H.; Law, R.; Bronstein, A.C.; Marraffa, J.M.; Spiller, H.A.; Hays, H.L.; Funk, A.R.; Mercurio-Zappala, M.; Calello, D.P.; et al. Cleaning and disinfectant chemical exposures and temporal associations with COVID-19—National Poison Data System, United States, 1 January 2020–31 March 2020. MMWR-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J.; DeFleur, M.L. A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrey, W. Media dependency during a large-scale social disruption: The case of 11 September. Mass Commun. Soc. 2004, 7, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.R. Communicating under uncertainty. In Interpersonal Processes: New Directions for Communication Research; Roloff, M.E., Miller, G.R., Roloff, M.E., Eds.; Sage: Newberry Park, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 14, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lachlan, K.A.; Spence, P.R.; Lin, X.L.; Najarian, K.; Del Greco, M. Social media and crisis management: CERC, search strategies, and Twitter content. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaye, R.J.; Sauer, M.; Ali, J.; Bernstein, J.; Wahl, B.; Barnhill, A.; Labrique, A. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, E277–E278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashers, D.E.; Neidig, J.L.; Haas, S.M.; Dobbs, L.K.; Cardillo, L.W.; Russell, J.A. Communication in the management of uncertainty: The case of persons living with HIV or AIDS. Commun. Monogr. 2000, 67, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Gay, C.D. Risk communication: Involvement, uncertainty, and control’s effect on information scanning and monitoring by expert stakeholders. Manag. Commun. Q. 1997, 10, 342–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströhle, A. Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Soo, J.; Boehm, J.K. Maintaining healthy behavior: A prospective study of psychological well-being and physical activity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, L.Y.; Franz, B. The role of news consumption and trust in public health leadership in shaping COVID-19 knowledge and prejudice. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 560828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L. COVID-19 information seeking on digital media and preventive behaviors: The mediation role of worry. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, H. Online information seeking and disease prevention intent during COVID-19 outbreak. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2022, 99, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesch, G.S.; Neto, W.L.B.D.; Storopoli, J.E. Media exposure and adoption of COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Brazil. New Media Soc. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dmour, H.; Masa’deh, R.; Salman, A.; Abuhashesh, M.; Al-Dmour, R. Influence of social media platforms on public health protection against the COVID-19 pandemic via the mediating effects of public health awareness and behavioral changes: Integrated model. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.C.; Fang, Y.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.B.; Hu, T.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.F.; Wang, Z.X. Parental acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years: Cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Pediatri. Parent. 2020, 3, e24827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galle, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Roma, P.; Da Molin, G.; Diella, G.; Montagna, M.T.; Ferracuti, S.; Liguori, G.; Orsi, G.B.; Napoli, C. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in the elderly: A cross-sectional study in southern Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Pacilli, M.G.; Aquino, A. TV news and COVID-19: Media influence on healthy behavior in public spaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T. The changes in the effects of social media use of cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Patni, N.; Sing, M.; Sood, A.; Singh, G. YouTube as a source of information on the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Yadav, K.; Yadav, N.; Ferdinand, K.C. Zika Virus pandemic—Analysis of Facebook as a social media health information platform. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, C. Infodemic vs. Pandemic factors associated to public anxiety in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study in China. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 723648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.O.; Bailey, A.; Huynh, D.; Chan, J. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: A pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.H.; Salathe, M. Early assessment of anxiety and behavioral response to novel Swine-origin Influenza A (H1N1). PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bults, M.; Beaujean, D.J.M.A.; de Zwart, O.; Kok, G.; van Empelen, P.; van Steenbergen, J.E.; Richardus, J.H.; Voeten, H.A.C.M. Perceived risk, anxiety, and behavioural responses of the general public during the early phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands: Results of three consecutive online surveys. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.C.; Lam, T.H.; Cheng, K.K. Mass masking in the COVID- 19 epidemic: People need guidance. Lancet 2020, 395, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CNN. Trump Mum on Hydroxychloroquine as Early Trials Falter, but Sick Americans Still Taking ‘Desperate Measures’ to Fill Prescriptions. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/22/politics/trump-hydroxychloroquine-shortages-black-market-coronavirus/index.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Forbes. Calls to Poison Centers Spike after the President’s Comments about Using Disinfectants to Treat Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertglatter/2020/04/25/calls-to-poison-centers-spike--after-the-presidents-comments-about-using-disinfectants-to-treat-coronavirus/?sh=5b38a1871157 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- CNN. Fearing Coronavirus, Arizona Man Dies after Taking a Form of Chloroquine Used to Treat Aquariums. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/23/health/arizona-coronavirus-chloroquine-death/index.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Tanir, Y.; Karayagmurlu, A.; Kaya, I.; Kaynar, T.B.; Turkmen, G.; Dambasan, B.N.; Meral, Y.; Coskun, M. Exacerbation of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishler, W.; Rose, R. What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comp. Polit. Stud. 2001, 34, 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Melado, F.J.; Di Pietro, M.L. The vaccine against COVID-19 and institutional trust. Enferm. Infec. Microbiol. Clin. 2021, 39, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervasti, H.; Kouvo, A.; Venetoklis, T. Social and institutional trust in times of crisis: Greece, 2002–2011. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 1207–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, K.; Aday, S.; Brewer, P.R. A panel study of media effects on political and social trust after 11 September 2001. Harv. Int. J. Press-Polit. 2004, 9, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron, A. Internet, news, and political trust: The difference between social media and online media outlets. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2015, 20, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laor, T.; Lissitsa, S. Mainstream, on-demand and social media consumption and trust in government handling of the COVID crisis. Online Inf. Rev. 2022, 46, 1335–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, J.; Alinead, D. Social media and trust in scientific expertise: Debating the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Soc. Med. Soc. 2020, 6, 205630512098105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Cvetkovich, G.; Roth, C. Salient value similarity, social trust, and risk/benefit perception. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, M.; Zingg, A. The role of public trust during pandemics implications for crisis communication. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Davila, A.; Regis, M.; Kraus, S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Glob. Transit. 2020, 2, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Mesch, G.S. The adoption of preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storopoli, J.; da Silva Neto, W.L.B.; Mesch, G.S. Confidence in social institutions, perceived vulnerability and the adoption of recommended protective behaviors in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G. Global evidence on the determinants of public trust in governments during the COVID-19. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, H.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Jhang, S. How to defend COVID-19 in Taiwan? Talk about people’s disease awareness, attitudes, behaviors and the impact of physical and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Johnston, R.M.; van der Linden, C. Public responses to policy reversals: The case of mask usage in Canada during COVID-19. Can. Public Policy-Anal. Polit. 2020, 46, S119–S126. [Google Scholar]

- Dohle, S.; Wingen, T.; Schreiber, M. Acceptance and adoption of protective measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of trust in politics and trust in science. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 15, e4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, A.B.; Shields, T. Who trusts the WHO? Heuristics and Americans’ trust in the World Health Organization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Q. 2021, 102, 2312–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, C.; Shen, F.; Yu, W.; Chu, Y. The relationship between government trust and preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: Exploring the roles of knowledge and negative emotion. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Herrera, A.M.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, D. The other side of COVID-19: Impact on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendau, A.; Petzold, M.B.; Pyrkosch, L.; Maricic, L.M.; Betzler, F.; Rogoll, J.; Grosse, J.; Strohle, A.; Plag, J. Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. Eur. Arch. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y. Media exposure and anxiety during COVID-19: The mediation effect of media vicarious traumatization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, J. Passive social media use and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social comparison and emotion regulation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Legrand, A.C.; Brier, Z.M.F.; Van, S.K.; Peck, K.; Dodds, P.S.; Danforth, C.M.; Adams, Z.W. Doomscrolling during COVID-19: The negative association between daily social and traditional media consumption and mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma 2022, 14, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabahang, R.; Aruguete, M.S.; McCutcheon, L. Online health information utilization and online news exposure as predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2020, 22, 469–482. [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson, G.J.G.; Taylor, S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: What all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 71, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Eisen, J.L. The epidemiology and clinical-features of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1992, 15, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, H. Letter from China: Covid-19 on the grapevine, on the internet, and in commerce. BMJ 2020, 368, m643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.; Wiwattanapantuwong, J.; Tuicomepee, A.; Suttiwan, P.; Watakakosol, R. Anxiety and public responses to Covid-19: Early data from Thailand. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 129, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Luo, W.-T.; Li, Y.; Li, C.-N.; Hong, Z.-S.; Chen, H.-L.; Xiao, F.; Xia, J.-Y. Psychological status and behavior changes of the public during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, A.; Matsubayashi, T.; Sueki, H.; Ueda, M. COVID-19 preventive behaviours among people with anxiety and depressive symptoms: Findings from Japan. Public Health 2020, 189, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.R. Improving access to, use of, and outcomes from public health programs: The importance of building and maintaining trust with patients/clients. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Arguel, A.; Neves, A.L.; Gallagher, A.M.; Kaplan, R.; Mortimer, N.; Mendes, G.A.; Lau, A.Y.S. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 2015, 22, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zung, W.W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 1971, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand-Sheiner, D.; Kol, O.; Frydman, S.; Levy, S. To be (vaccinated) or not to be: The effect of media exposure, institutional trust, and incentives on attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S.; Sripad, P. How do you measure trust in the health system? A systematic review of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 91, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargain, O.; Aminjonov, U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2020, 192, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A.; Wright, L. The cummings effect: Politics, trust, and behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 396, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Lyu, Z. Trust, risk perception, and COVID-19 infections: Evidence from multilevel analyses of combined original dataset in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, A.; McBryde, E.; Adegboye, O.A. Does high public trust amplify compliance with stringent COVID-19 government health guidelines? A multi-country analysis using data from 102,627 individuals. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, J.C.; Lee, N.M.; Pressgrove, G. Reassessing the variables used to measure public perceptions of scientists. Sci. Commun. 2021, 43, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Percentage | n |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 45.9% | 513 |

| Female | 54.1% | 604 |

| Age | ||

| <18 | 4.1% | 46 |

| 18–25 | 30.6% | 342 |

| 26–30 | 22.6% | 252 |

| 31–35 | 23.5% | 263 |

| 36–40 | 9% | 101 |

| 41–50 | 7.6% | 85 |

| 51–60 | 2.3% | 26 |

| >60 | 0.2% | 2 |

| Education | ||

| Primary school | 0.8% | 9 |

| Junior high | 3.7% | 41 |

| High school | 8.2% | 92 |

| College/university | 79.8% | 892 |

| Master’s, doctoral degrees and above | 7.5% | 84 |

| Health Condition | ||

| Very poor | 0.1% | 1 |

| Relatively poor | 2.0% | 22 |

| Average | 24.0% | 268 |

| Relatively good | 53.6% | 599 |

| Very good | 20.3% | 227 |

| Place of Residence | ||

| Hubei province | 23.0% | 257 |

| Other provinces | 77.0% | 860 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent on pandemic information (1) | 1 | 0.24 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.06 | 0.23 *** |

| Official government media use (2) | 1 | 0.35 *** | 0.07 * | 0.26 *** | 0.09 ** | 0.06 | |

| Commercial media use (3) | 1 | 0.17 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.01 | 0.22 *** | ||

| Anxiety (4) | 1 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.60 *** | |||

| Institutional trust (5) | 1 | 0.29 *** | 0.03 | ||||

| Protective behavior (6) | 1 | 0.10 * | |||||

| Overprotective behavior (7) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Liu, C. Protective and Overprotective Behaviors against COVID-19 Outbreak: Media Impact and Mediating Roles of Institutional Trust and Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021368

Liu Y, Liu C. Protective and Overprotective Behaviors against COVID-19 Outbreak: Media Impact and Mediating Roles of Institutional Trust and Anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021368

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yi, and Cong Liu. 2023. "Protective and Overprotective Behaviors against COVID-19 Outbreak: Media Impact and Mediating Roles of Institutional Trust and Anxiety" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021368

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Liu, C. (2023). Protective and Overprotective Behaviors against COVID-19 Outbreak: Media Impact and Mediating Roles of Institutional Trust and Anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021368