The Effects of Virtual Reality on Enhancement of Self-Compassion and Self-Protection, and Reduction of Self-Criticism: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Information Sources

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

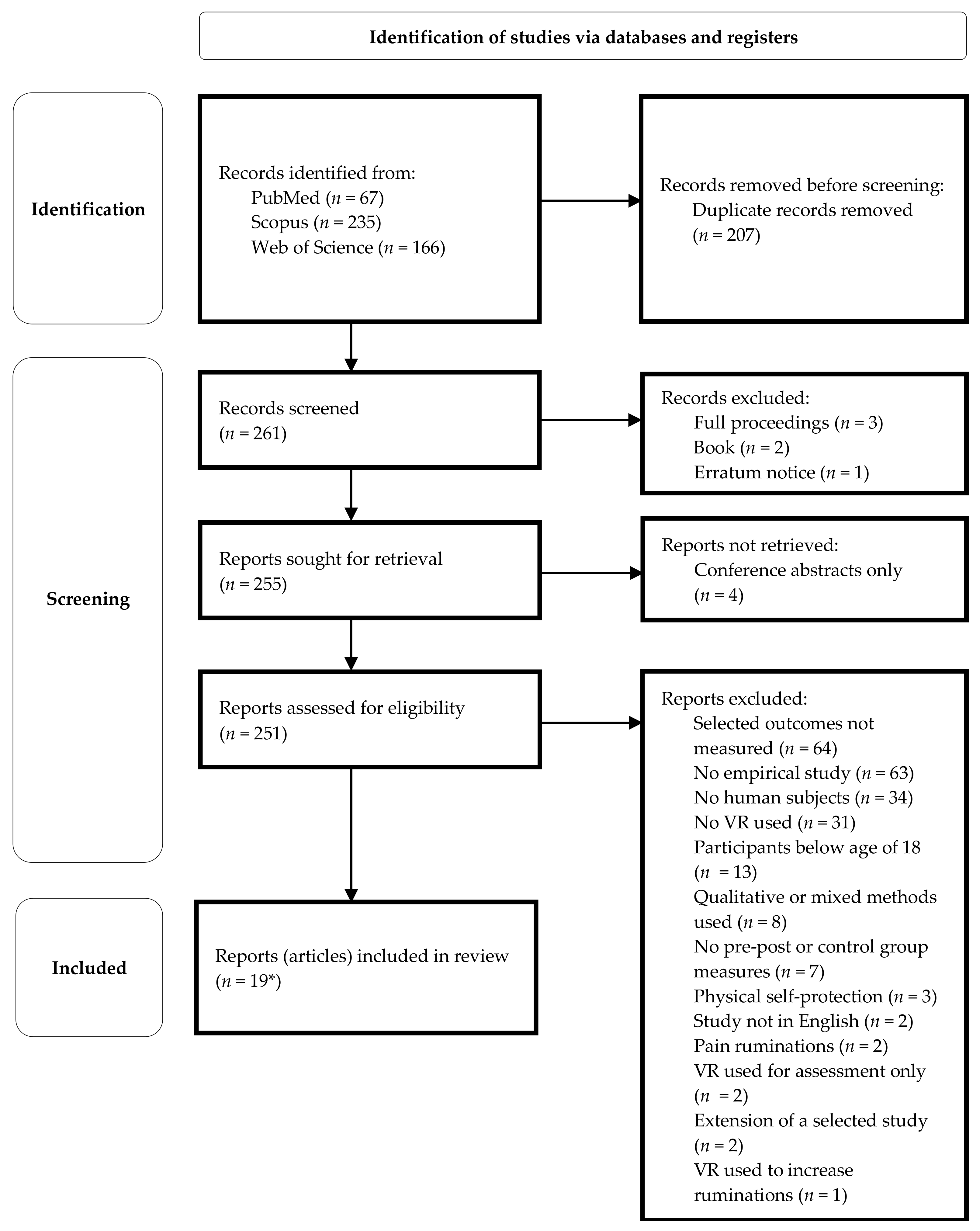

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection

- Type of the study design; studies were defined according to the purpose of this systematic review (i.e., even though a study had a control group, if the control group was not used as a comparison for the intervention group in respect to our outcomes, we treated it as a within-group study).

- The components of each intervention and, where available, the duration of each component; and the total duration of VR exposure one participant in the intervention group received.

- Whether participants in the control group received VR exposure too or not.

- The content of each VR intervention.

- Immersion and interactivity of VR technology used.

- The type of sample used in the study and their age.

- The size of intervention and control group(s).

- What outcomes, according to the focus of this systematic review, were measured (self-compassion, self-protection, assertiveness, negative ruminations, or self-criticism) and how (names of relevant measuring tools used, if available).

- The results of relevant outcomes as measured in point #8.

2.6. Risk of Bias and Certainty Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Self-Criticism

3.2. Self-Compassion

3.3. Self-Protection

3.4. Adverse Effects

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search Topic | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Virtual reality + Self-criticism | (“virtual reality” [Title/Abstract] OR “VR” [Title/Abstract] OR “virtual environment*” [Title/Abstract] OR “virtual world*” [Title/Abstract] OR “avatar” [Title/Abstract] OR “serious game*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“self-critic*” [Title/Abstract] OR “inner critic*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-contempt*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-hat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-attack*” [Title/Abstract] OR “ruminat*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-judg*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (english [Filter]) |

| Virtual reality + Self-compassion | (“virtual reality” [Title/Abstract] OR “VR” [Title/Abstract] OR “virtual environment*” [Title/Abstract] OR “virtual world*” [Title/Abstract] OR “avatar” [Title/Abstract] OR “serious game*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“self-compassion*” [Title/Abstract] OR “compassion*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-sooth*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-reassur*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (english [Filter]) | |

| Virtual reality + Self-protection | (“virtual reality” [Title/Abstract] OR “VR” [Title/Abstract] OR “virtual environment*” [Title/Abstract] OR “virtual world*” [Title/Abstract] OR “avatar” [Title/Abstract] OR “serious game*” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“self-protecti*” [Title/Abstract] OR “protective anger” [Title/Abstract] OR “assertive anger” [Title/Abstract] OR “assertive*” [Title/Abstract] OR “self-assert*” [Title/Abstract] OR “fierce self-compassion” [Title/Abstract]) AND (english [Filter]) | |

| Scopus | Virtual reality + Self-criticism | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment*” OR “virtual world*” OR “avatar” OR “serious game*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“self-critic*” OR “inner critic*” OR “self-contempt*” OR “self-hat*” OR “self-attack*” OR “ruminat*” OR “self-judg*”) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,”English”)) |

| Virtual reality + Self-compassion | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment*” OR “virtual world*” OR “avatar” OR “serious game*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“self-compassion*” OR “compassion*” OR “self-sooth*” OR “self-reassur*”) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,”English”)) | |

| Virtual reality + Self-protection | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment*” OR “virtual world*” OR “avatar” OR “serious game*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“self-protecti*” OR “protective anger” OR “assertive anger” OR “assertive*” OR “self-assert*” OR “fierce self-compassion”) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,”English”)) | |

| Web of Science | Virtual reality + Self-criticism | ((TS = (“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment*” OR “virtual world*” OR “avatar” OR “serious game*”)) AND (TS = (“self-critic*” OR “inner critic*” OR “self-contempt*” OR “self-hat*” OR “self-attack*” OR “ruminat*” OR “self-judg*”))) AND LA = (English) |

| Virtual reality + Self-compassion | ((TS = (“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment*” OR “virtual world*” OR “avatar” OR “serious game*”)) AND (TS = (“self-compassion*” OR “compassion*” OR “self-sooth*” OR “ self-reassur *”))) AND LA = (English) | |

| Virtual reality + Self-protection | ((TS = (“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment*” OR “virtual world*” OR “avatar” OR “serious game*”)) AND (TS = (“self-protecti*” OR “protective anger” OR “assertive anger” OR “assertive*” OR “self-assert*” OR “fierce self-compassion”))) AND LA = (English) |

Appendix B

| Reference | Bias | Judgement | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascone et al., 2020 [45] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…participants were randomized…” Comment: Randomization method unclear. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…participants were randomized…” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment unclear. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “… after participants were randomized and received a psycho-educative video, depending upon their assignment…” Comment: Researchers knew who was in intervention and in control group. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “We used a brief experimental version of the original Self-Compassion Scale…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | Unclear risk | Comment: Unclear whether participants were observed during the intervention. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…clear limitation of our study is the small sample size…” Comment: Small sample increases the impact of chance on the results. No power analysis mentioned. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “ Representativeness of the sample is also questionable, as it mainly consisted of highly educated, young individuals (students).” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…we used non-parametric within-group difference analyses…” Comment: Two within-group statistical analyses decrease ecological validity compared with one between-group analysis. | |

| Cebolla et al., 2019 [42] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Participants who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of the two study condition…using the Random Allocation Software 2.0.” Comment: Randomization method specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Participants who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of the two study condition…using the Random Allocation Software 2.0.” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment unclear. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “…to induce this experience, the TMTBA-VR has the support of a performer, a person who is trained to mimic the user’s movements to induce the embodied illusion.” Comment: The intervention was delivered with the help of staff who were part of the intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Self-Other Four Immeasurable Scale… is a 16-item scale, rated on a five-point Likert scale,” (and) “Mindfulness Self-Care… measures the self-reported frequency of self-care behaviors.” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “…to induce this experience, the TMTBA-VR has the support of a performer, a person who is trained to mimic the user’s movements to induce the embodied illusion.” Comment: Participants were aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The size of the sample has been determined with the G-Power program…” Comment: Sample size determined by power calculations. However, this sample size appears to be very small regardless. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “The sample was composed of 16 students from the University of Valencia…” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| Other Bias: (other)–MSCS | Unclear risk | Quote: “…results…should be viewed with caution because the internal consistencies of these subscales were not adequate.” Comment: Some statistical analysis may be invalid for MSCS measures due to low internal consistencies of two subscales. | |

| Falconer et al., 2014 [35] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: The study followed an experimental design; however, it is not explicitly said that the participants were randomly assigned to given conditions. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: The study followed an experimental design; however, it is not explicitly said that the participants were randomly assigned to given conditions. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “…participants were guided through the same exercises as before to become accustomed to their environment from this new perspective and, in the 1PP, to their new body. Participants in the 3PP condition did not have a virtual body.” Comment: Researchers were aware of the intervention they were delivering. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Participants are instructed to imagine, as vividly as possible, that these scenarios are happening to them at the current moment in time and rate on 7-point Likert scales…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Three participants were excluded in the 3PP version for technical reasons…” Comment: Three participants out of 24 were excluded from the data analysis due to technical reasons. Attrition happened in one group only, which may have had an impact on the results. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “After this, participants were fitted with the head mounted display (HMD) and body tracking suit…” (and) “For the second stage of the experiment participants were seated on one of the stools opposite a seated crying child avatar…” Comment: Participants were likely aware of being monitored during the intervention. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “Twenty-two females, completed the first person perspective condition and twenty-one females completed the third person perspective condition.” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| Falconer et al., 2016 [8] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Comment: No control group. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Participants are instructed to imagine that these scenarios are happening to them now and rate on 7-point scales from…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: “…1 did not complete due to time commitments and 1 did not complete because she found hearing her voice played back to her aversive.” (and) “We were unable to obtain end-of intervention data from two participants. We therefore repeated the analyses on the entire sample, testing for changes between baseline and follow-up only. These yielded identical findings and are not reported further.” Comment: Missing data addressed. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (maturation bias) | High risk | Quote: “… the absence of the kind of control condition…” Comment: Some effect of time is possible, as there was approximately a 6-week gap between the first intervention and follow-up, and there was no control group to compare outcomes with. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “…participants were asked to close their eyes to complete the body ownership questions, which were recited to them and their responses were recorded by the researcher.” Comment: Participants were likely aware of being monitored during the intervention. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…within the context of the study limitations. Chief among these was the relatively small number of patients…” Comment: No power analysis mentioned in the article. | |

| Other Bias: (chance bias) | High risk | Comment: Potentially small sample, and no control group to compare baseline measures with. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “Ten patients were currently on antidepressant medication, seven were currently receiving psychological therapy…” Comment: Possible impact of other interventions outside of this study. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…the repetition of a single immersive virtual reality scenario…” Comment: The same scenario was repeated three times, which may have led to repetition or boredom. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “Other limitations include the repeated use of the SCCS, which may have diminished the validity of the measure…” Comment: The same questionnaire was used three times, which may have led to its diminished validity. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…the absence of the kind of control condition we previously employed…” Comment: Lack of control group may lead to overestimation of results. | |

| Hur et al., 2021 [47] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “We recruited individuals with and without social anxiety disorder…” Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “We recruited individuals with and without social anxiety disorder…” Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “The researchers stayed with the participants throughout the VR sessions to address emergencies such as extreme anxiety or panic attacks.” Comment: Researchers knew who was in intervention group. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “All participants…completing self-report questionnaires, including… Post-Event Rumination Scale…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote: “We initially recruited and enrolled 40 individuals with social anxiety disorder… 21 participants completed the VR session and postintervention assessments.” Comment: High attrition rate. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Outcome measures not fully defined in the protocol. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “The researchers stayed with the participants throughout the VR sessions to address emergencies such as extreme anxiety or panic attacks.” Comment: Participants were likely aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The recommended sample size for a task fMRI is 20; our sample size (n = 25 in the social anxiety disorder group at baseline, n = 21 in the social anxiety disorder group at follow-up) seemed to have adequate statistical power.” Comment: No power calculation for sample size, only a recommendation. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “From the second session onward, the participants were asked to select the level of difficulty they desired.” Comment: Intervention appears, to some extent, inconsistent across the intervention group. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…the case-control study using sham was not properly performed. Therefore, there is a limitation in interpretation to determine the effect of VR therapy through this study. Second, the lack of a direct comparison with conventional face-to-face therapy should be considered when interpreting these findings.” Comment: Lack of control group for rumination scores may lead to overestimation of results. | |

| Kim et al., 2020 [48] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “We recruited individuals for the SAD and healthy control groups…” Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “We recruited individuals for the SAD and healthy control groups…” Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “Researchers were present throughout the VR experience to deal with any unexpected situations.” Comment: Researchers knew who was in intervention group. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “…this study employed self-rated scales that could be confounded by bias…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote: “…8 patients with SAD and 1 healthy control participant dropped out for personal reasons (e.g., time constraints).” Comment: Potentially high and uneven attrition rate [8 out of 40 (20%) in intervention group]. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Outcome measures not fully defined in the protocol. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “Researchers were present throughout the VR experience to deal with any unexpected situations.” Comment: Participants were likely aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…a total of 32 patients with SAD and 33 healthy control participants completed this study.” Comment: No power calculation mentioned in the article. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “During the second session, participants could select and proceed to their desired level.” Comment: Intervention appears, to some extent, inconsistent across the intervention group. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “Participants answered the self-reported psychological scales four times: at baseline (before the VR experience), after the second VR session, after the fourth session, and after termination (i.e., after the sixth session).” Comment: The same questionnaire was used four times, which may have led to its diminished validity. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…this study did not have a sham or waitlist control group, which limits interpretation of the results.” Comment: Lack of control group may lead to overestimation of results. | |

| Klinger et al., 2004; 2005 [41,40] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Participants in the two conditions were matched based on the following variables: gender, age, duration, severity of social phobia…, ability to use computers or virtual reality software, and time availability for some groups that were already prescheduled.” Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Participants in the two conditions were matched based on the following variables: gender, age, duration, severity of social phobia…, ability to use computers or virtual reality software, and time availability for some groups that were already prescheduled.” Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “Each session was individual and directed by a cognitive behavior therapist.” Comment: The therapists were present during the intervention and likely knew they were delivering an actual intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “The Rathus Assertiveness Schedule is a self-report that measures social assertiveness.” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “Each session was individual and directed by a cognitive behavior therapist.” Comment: The therapist was present during the study, so participants were aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (chance bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Participants in the two conditions were matched based on the following variables: gender, age, duration, severity of social phobia…, ability to use computers or virtual reality software, and time availability for some groups that were already prescheduled.” Comment: Participants appear to be manually matched rather than randomly split. | |

| Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021 [49] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Assignation of the subjects was performed… through a simple randomization sequence generated by computer.” Comment: Randomization method specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Assignation of the subjects was performed after the baseline evaluation by a member of the research group, who had no knowledge about the study aims and was not involved in the study in any other way…” Comment: Allocation process was blinded. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “…providers and participants were able to know what kind of intervention they were offering and receiving, respectively…” Comment: Researchers knew what intervention they were delivering. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “…the assessment was conducted using self-reported measures, which could introduce some bias…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “‘MBP + VR’ had a significantly higher number of participants who attended 3 or more sessions: 89 (95.7%), compared to 77 (82.8%) in the ‘MBP’ group, and 66 (70.2%) in the ‘Relaxation’ group (Fisher p < .001).” Comment: Overall, 92 of 280 (33%) participants dropped out between baseline and follow-up. There is a big difference in drop-out rates across the three conditions. It was, however, part of the intervention to increase adherence, so rather than an uneven drop-out rate, this could be the effect of the intervention. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: A number of secondary measures defined in the registered protocol were not reported in the published study; this is not the case for self-compassion, though, which is one of the domains of this systematic review. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “…the implementation of VR exercises was performed by another clinical psychologist…” Comment: Participants were likely aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…the sample was mostly comprised of females, students of health-related degrees and from only one city (Zaragoza, Spain), which implies that our results should not be considered representative of the whole Spanish undergraduate population.” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| Navarrete et al., 2021 [50] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of the two study conditions…using Random Allocation Software 2.0.” Comment: Randomization method specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of the two study conditions…using Random Allocation Software 2.0.” Comment: Randomization sequences concealment not specified. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “Two researchers were present in all sessions to run the experiment…” Comment: The researchers were present during the intervention and knew they were delivering an actual intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “… state self-compassion…levels were assessed with the Visual analogue scales…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Three participants out of 44 dropped out—one out of 22 in the intervention group and two out of 22 in the control group. The drop-out rate could be considered even, but overall it is more than 5%. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Protocol not available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “Two researchers were present in all sessions to run the experiment…” Comment: Participants were likely aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “Professionals from healthcare institutions or healthcare students were invited to participate in a study aimed at increasing their compassionate skills toward their patients.” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| O’Gara et al., 2022 [51] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Potential participants were identified by clinical teams, and a diverse convenience sample undergoing a range of cancer treatments across tumour types from one specialist centre recruited.” Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Potential participants were identified by clinical teams, and a diverse convenience sample undergoing a range of cancer treatments across tumour types from one specialist centre recruited.” Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Comment: No control group. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “The SCS is a 26-item instrument that measures self-compassion… according to a five-point scale (1 = almost never; 5 = almost always).” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote: “Acceptability of the intervention was deemed satisfactory as >60% (N = 13; 65%) of participants completed all three sessions.” Comment: However, only 10 participants completed SCS according to article’s supplementary tables—the reasons for further dropouts are unclear. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Protocol not available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (maturation bias) | High risk | Quote: “… planned appointments, spaced at least a week apart.” Comment: The average duration of full VR treatment unclear. Additionally, no control group for comparison. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | Unclear risk | Comment: Unclear whether researchers were present while patients underwent the intervention. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The small sample did not allow for adjustment of confounding variables in the quantitative analysis so that any notable differences in baseline characteristics or response to the intervention in the study population could be identified.” Comment: Small sample. Additionally, no power calculation reported. | |

| Other Bias: (chance bias) | High risk | Comment: Potentially small sample and no control group to compare collected scores with. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Comment: The same questionnaire was used four times, which may have led to its diminished validity. | |

| Park & Ogle, 2021 [53] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the study groups…” Comment: Randomization method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the study groups…” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment not specified. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “When each participant entered the room, a researcher offered her a bottle of water, demonstrated the avatar viewing tools for her, and allowed her to practice until she felt comfortable.” Comment: Researchers knew they were delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “…computed subscale scores on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from almost never (1) to almost always (5), to generate a total score of self-compassion.” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…we recruited eighteen female adults…” Comment: No power calculation reported. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “The total duration of completing the virtual avatar experience ranged from 4 to 13 min.” Comment: The VR intervention may have been inconsistent across the participants. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “…we recruited a convenient sample of young college female students with some level of body image concern from a U.S. 4-year university, representing a single geographical location.” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Comment: The study appears not to have included the control group in the analysis. | |

| Park et al., 2011 [52] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…they were randomly assigned to either SST-TR (n = 45) or SST-VR (n = 46).” Comment: Randomization method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “…they were randomly assigned to either SST-TR (n = 45) or SST-VR (n = 46).” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment not specified. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “Every session included a therapist modeling followed by the participant’s role-playing…” Comments: Researchers knew they were delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “For secondary outcomes, we selected three self-reports…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote: “…no difference between the two groups in the drop-out rate…” (and) “All missing values in the post-session questionnaire and test were due to the participants’ absences. These were substituted by a within-group average.” Comment: A total of 28 out of 91 (31%) participants dropped out. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “Every session included a therapist modeling followed by the participant’s role-playing…” Comments: Participants were aware they were observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “This study enrolled 91 participants…” Comment: No power calculation for sample size reported. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “This study enrolled 91 participants with schizophrenia who were all inpatients of the Severance Mental Health Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine.” Comment: The results may be applicable to one specific population only. | |

| Price & Anderson, 2011 [54] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “The randomization procedure was administered by the project coordinator, using a random number generator according to ID number.” Comment: Randomization method specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Participants were randomly assigned using a simple randomization procedure.” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment not specified. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “The therapist was able to communicate with the participant through a microphone to encourage sustained contact with the feared stimuli.” Comment: The therapist was aware that s/he was delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “The RQ is a 5-item self-report questionnaire…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: A total of 26 of 91 (29%) participants dropped out during the study; 20% in intervention and 35% in control condition. High and uneven drop-out rate. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “The therapist was able to communicate with the participant through a microphone to encourage sustained contact with the feared stimuli.” Comment: Participants were likely aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Participants were 91 individuals diagnosed with social anxiety.” Comment: No power calculation for sample size reported. | |

| Other Bias: (recall bias) | High risk | Quote: “The current study examined PEP for the previous week at the end of an exposure therapy session, which renders it vulnerable to recall bias.” Comment: Potential interference from current exposure. | |

| Other Bias: (other) | High risk | Quote: “Participants were given self-report measures prior to being randomized to a condition (pretreatment), at the end of the fourth session (mid-treatment), and at the end of the eighth session (posttreatment).” Comment: The same questionnaire was used three times, which may have led to its diminished validity. | |

| Other Bias: (sampling bias) | High risk | Quote: “Also, the rate of co-morbidity in the current sample (12%) deserves mention, as it is lower than what is typically found for individuals with social anxiety disorder.” Comment: Results may not be applicable to all individuals with social anxiety disorder. | |

| Riva et al., 2001 [11] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The sample was randomly divided into two groups…” Comment: Randomization method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The sample was randomly divided into two groups…” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment not specified. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “In all the sessions, the therapists follow the Socratic style: they use a series of questions, related to the contents of the virtual environment, to help clients synthesize information and reach conclusions on their own.” Comment: Therapists know they are delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Italian version…of the assertion inventory (AI)…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “In all the sessions, the therapists follow the Socratic style: they use a series of questions, related to the contents of the virtual environment, to help clients synthesize information and reach conclusions on their own.” Comment: Participants knew they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The individuals included were 28 women…” Comment: No power analysis for sample size reported. | |

| Riva et al., 2002 [55] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The sample was randomly divided into two groups…” Comment: Randomization method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The sample was randomly divided into two groups…” Comment: Randomization sequence concealment not specified. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “In all the sessions, the therapists follow the Socratic style: they use a series of questions, related to the contents of the virtual environment, to help clients synthesize information and reach conclusions on their own.” Comment: Therapist know they are delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “Italian version…of the assertion inventory (AI)…” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “In all the sessions, the therapists follow the Socratic style: they use a series of questions, related to the contents of the virtual environment, to help clients synthesize information and reach conclusions on their own.” Comment: Participants knew they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The individuals included were 20 women…” Comment: No power analysis for sample size reported. | |

| Roy et al., 2003 [56] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “Each session is individual and directed by a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist.” Comment: The therapist was present during the study, so s/he was aware of delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “The Rathus Assertiveness Schedule is a self-report questionnaire enabling to measure the degree of assertiveness.” Comment: Outcome assessment could not be blinded due to self-report measures. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: None of the participants dropped out during the study. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “Each session is individual and directed by a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist.” Comment: The therapist was present during the study, so participants were aware they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “A preliminary study compared 10 subjects…” Comment: No power calculation reported. | |

| Rus-Calafell et al., 2012 [57] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: A case study with only one participant. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: A case study with only one participant. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Comment: A case study with only one participant. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “The self-report score for assertiveness (AI) also showed…” (and) “…assertive behaviors (measured by a specific social interaction activity)…” Comment: Apart from self-report, there were also behavioral measures used to assess the intervention. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | N/A | Comment: A case study with only one participant. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (maturation bias) | High risk | Quote: “The treatment consisted of 16 twice-weekly sessions…” Comment: Time may have played some role as the treatment lasted 8 weeks. No control group. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “…the therapist and the patient dealt with social anxiety and interpersonal interactions…” Comment: The patient knew she was being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | High risk | Comment: A case study with only one participant. | |

| Other Bias: (chance bias) | High risk | Comment: A case study with only one participant. | |

| Rus-Calafell et al., 2014 [15] | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: No randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: No randomization. | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Comment: No control group. Researchers knew they were delivering an intervention. | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Assertion inventory (…). This is a self-reported questionnaire…” (and) “Assertive behaviors. This score comprises the number of correct emitted assertive behaviors and the correct identification of assertive, passive and aggressive behaviors/communication styles of others…” Comment: Apart from self-report, also behavioral measures used to assess the intervention. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote: “Fifteen patients were enrolled, and twelve completed the study.” (and) “Three of the participants abandoned the study because they missed more than 3 consecutive sessions; their reported reasons were as follows: illness, schedule incompatibilities and forgetfulness.” Comment: An amount of 20% attrition may have affected the outcomes. | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No protocol available. | |

| Other Bias: (social desirability bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Not reported. | |

| Other Bias: (maturation bias) | High risk | Quote: “The therapy took place across sixteen “one-on-one” sessions, conducted twice a week over eight weeks.” (and) “After the complementation of the treatment, the post-assessment was performed, and the patients were given an appointment four months later for the follow-up assessment.” Comment: The whole procedure lasted 6 months, so time may have played some part in the outcomes. No control group involved. | |

| Other Bias: (Hawthorne effect) | High risk | Quote: “At the end of the intervention, participants were asked to complete an anonymous satisfaction questionnaire and rate their perception of (…) the therapist’s work…” Comment: Participants likely knew they were being observed. | |

| Other Bias: (small sample size) | Unclear risk | Quote: “Fifteen patients were enrolled, and twelve completed the study.” Comment: No power calculation for sample size reported. | |

| Other Bias: (chance bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The reported results are based on a small, uncontrolled pilot study.” Comment: Potentially small sample and no control group to compare baseline measures with. |

References

- Wiederhold, B.K. Lessons Learned as We Begin the Third Decade of Virtual Reality. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, B.K.; Riva, G. Virtual Reality Therapy: Emerging Topics and Future Challenges. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, G. Virtual Reality in Clinical Psychology. In Comprehensive Clinical Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.A.; Buckwalter, J.G.; Neumann, U. Virtual Reality and Cognitive Rehabilitation: A Brief Review of the Future. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 1997, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Koenig, S.T. Is clinical virtual reality ready for primetime? Neuropsychology 2017, 31, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Reeve, S.; Robinson, A.; Ehlers, A.; Clark, D.; Spanlang, B.; Slater, M. Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding, and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Neira, C.; Sandin, D.J.; DeFanti, T.A. Surround-screen projection-based virtual reality: The design and implementation of the CAVE. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH ’93 20th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Anaheim, CA, USA, 2–6 August 1993; Whitton, M.C., Ed.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, C.; Rovira, A.; King, J.; Gilbert, P.; Antley, A.; Fearon, R.; Ralph, N.; Slater, M.; Brewin, C.R. Embodying self-compassion within virtual reality and its effects on patients with depression. BJPsych Open 2016, 2, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Haselton, P.; Freeman, J.; Spanlang, B.; Kishore, S.; Albery, E.; Denne, M.; Brown, P.; Slater, M.; Nickless, A. Automated psychological therapy using immersive virtual reality for treatment of fear of heights: A single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshuis, L.; van Gelderen, M.; van Zuiden, M.; Nijdam, M.; Vermetten, E.; Olff, M.; Bakker, A. Efficacy of immersive PTSD treatments: A systematic review of virtual and augmented reality exposure therapy and a meta-analysis of virtual reality exposure therapy. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 143, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Bacchetta, M.; Baruffi, M.; Molinari, E. Virtual Reality–Based Multidimensional Therapy for the Treatment of Body Image Disturbances in Obesity: A Controlled Study. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2001, 4, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, N.; Randall, H.; Choksi, H.; Gao, A.; Vaughan, C.; Poronnik, P. Virtual Reality interventions for acute and chronic pain management. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 114, 105568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Raza, K. Towards a VIREAL Platform: Virtual Reality in Cognitive and Behavioural Training for Autistic Individuals. In Advanced Computational Intelligence Techniques for Virtual Reality in Healthcare; Gupta, D., Hassanien, A.E., Khanna, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Tuente, S.; Bogaerts, S.; Bulten, E.; Vos, M.K.-D.; Vos, M.; Bokern, H.; Van Ijzendoorn, S.; Geraets, C.N.W.; Veling, W. Virtual Reality Aggression Prevention Therapy (VRAPT) versus Waiting List Control for Forensic Psychiatric Inpatients: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus-Calafell, M.; Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J.; Ribas-Sabaté, J. A virtual reality-integrated program for improving social skills in patients with schizophrenia: A pilot study. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2014, 45, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Tiller, J.W.G. Depression and anxiety. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, S28–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcaccia, B.; Salvati, M.; Pallini, S.; Baiocco, R.; Curcio, G.; Mancini, F.; Vecchio, G.M. Interpersonal Forgiveness and Adolescent Depression. The Mediational Role of Self-reassurance and Self-criticism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, G. Erosion: The Psychopathology of Self-Criticism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Timulak, L.; Pascual-Leone, A. New Developments for Case Conceptualization in Emotion-Focused Therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 22, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, L. Emotion–focused therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2004, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, B.; Bar-Kalifa, E.; Alon, E. Emotion-focused therapy for social anxiety disorder: Results from a multiple-baseline study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, B.; Carlin, E.R.; Engle, D.E.; Hegde, J.; Szepsenwol, O.; Arkowitz, H. A Pilot Investigation of Emotion-Focused Two-Chair Dialogue Intervention for Self-Criticism. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Girz, L. Overcoming shame and aloneness: Emotion-focused group therapy for self-criticism. Pers.-Cent. Exp. Psychother. 2020, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timulak, L.; Keogh, D.; Chigwedere, C.; Wilson, C.; Ward, F.; Hevey, D.; Griffin, P.; Jacobs, L.; Hughes, S.; Vaughan, C.; et al. A comparison of emotion-focused therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: Results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy 2022, 59, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Tirch, D. Self-compassion and ACT. In Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: The Seven Foundations of Well-Being; Kashdan, T.B., Ciarrochi, J., Eds.; Context Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 78–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, J.L.; Keltner, D.; Simon-Thomas, E. Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. An Introduction to Compassion Focused Therapy in Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2010, 3, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, C.; Taylor, B.L.; Gu, J.; Kuyken, W.; Baer, R.; Jones, F.; Cavanagh, K. What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 47, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Leone, A.; Greenberg, L.S. Emotional processing in experiential therapy: Why “the only way out is through”. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak Up, Claim Their Power, and Thrive; Penguin Life: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K.D.; Dahm, K.A. Self-compassion: What it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness. In Handbook of Mindfulness and Self-Regulation; Ostafin, B., Robinson, M., Meier, B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, C.; Slater, M.; Rovira, A.; King, J.; Gilbert, P.; Antley, A.; Brewin, C.R. Embodying Compassion: A Virtual Reality Paradigm for Overcoming Excessive Self-Criticism. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 89, 105906. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Grimes, D.A. Sample size slippages in randomised trials: Exclusions and the lost and wayward. Lancet 2002, 359, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Hill, S. How to GRADE the Quality of the Evidence; Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, E.; Bouchard, S.; Légeron, P.; Roy, S.; Lauer, F.; Chemin, I.; Nugues, P. Virtual Reality Therapy Versus Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Social Phobia: A Preliminary Controlled Study. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinger, E.; Légeron, P.; Roy, S.; Chemin, I.; Lauer, F.; Nugues, P. Virtual reality exposure in the treatment of social phobia. In Cybertherapy: Internet and Virtual Reality as Assessment and Rehabilitation Tools for Clinical Psychology and Neuroscience; Riva, G., Botella, C., Légeron, P., Optale, G., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla, A.; Herrero, R.; Ventura, S.; Miragall, M.; Bellosta-Batalla, M.; Llorens, R.; Baños, R.M. Putting Oneself in the Body of Others: A Pilot Study on the Efficacy of an Embodied Virtual Reality System to Generate Self-Compassion. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook-Cottone, C.P.; Guyker, W.M. The Development and Validation of the Mindful Self-Care Scale (MSCS): An Assessment of Practices that Support Positive Embodiment. Mindfulness 2017, 9, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Sears, S. Measuring the Immeasurables: Development and Initial Validation of the Self-Other Four Immeasurables (SOFI) Scale Based on Buddhist Teachings on Loving Kindness, Compassion, Joy, and Equanimity. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 92, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascone, L.; Ney, K.; Mostajeran, F.; Steinicke, F.; Moritz, S.; Gallinat, J.; Kühn, S. Virtual Reality for Individuals with Occasional Paranoid Thoughts. In Proceedings of the CHI 2020: Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascone, L.; Sundag, J.; Schlier, B.; Lincoln, T.M. Feasibility and Effects of a Brief Compassion-Focused Imagery Intervention in Psychotic Patients with Paranoid Ideation: A Randomized Experimental Pilot Study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.-W.; Shin, H.; Jung, D.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, S.; Kim, G.J.; Cho, C.-Y.; Choi, S.; Lee, S.-M.; Cho, C.-H. Virtual Reality–Based Psychotherapy in Social Anxiety Disorder: fMRI Study Using a Self-Referential Task. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e25731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Lee, S.; Jung, D.; Hur, J.-W.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, S.; Kim, G.J.; Cho, C.-Y.; Choi, S.; Lee, S.-M.; et al. Effectiveness of a Participatory and Interactive Virtual Reality Intervention in Patients with Social Anxiety Disorder: Longitudinal Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrego-Alarcón, M.; López-Del-Hoyo, Y.; García-Campayo, J.; Pérez-Aranda, A.; Navarro-Gil, M.; Beltrán-Ruiz, M.; Morillo, H.; Delgado-Suarez, I.; Oliván-Arévalo, R.; Montero-Marin, J. Efficacy of a mindfulness-based programme with and without virtual reality support to reduce stress in university students: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2021, 142, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, J.; Martínez-Sanchis, M.; Bellosta-Batalla, M.; Baños, R.; Cebolla, A.; Herrero, R. Compassionate Embodied Virtual Experience Increases the Adherence to Meditation Practice. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gara, G.; Murray, L.; Georgopoulou, S.; Anstiss, T.; Macquarrie, A.; Wheatstone, P.; Bellman, B.; Gilbert, P.; Steed, A.; Wiseman, T. SafeSpace: What Is the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Codesigned Virtual Reality Intervention, Incorporating Compassionate Mind Training, to Support People Undergoing Cancer Treatment in a Clinical Setting? BMJ Open 2022, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-M.; Ku, J.; Choi, S.-H.; Jang, H.-J.; Park, J.-Y.; Kim, S.I.; Kim, J.-J. A virtual reality application in role-plays of social skills training for schizophrenia: A randomized, controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 189, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ogle, J.P. How virtual avatar experience interplays with self-concepts: The use of anthropometric 3D body models in the visual stimulation process. Fash. Text. 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Anderson, P.L. The impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on post event processing among those with social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, G.; Bacchetta, M.; Baruffi, M.; Molinari, E. Virtual-reality-based multidimensional therapy for the treatment of body image disturbances in binge eating disorders: A preliminary controlled study. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2002, 6, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Klinger, E.; Légeron, P.; Lauer, F.; Chemin, I.; Nugues, P. Definition of a VR-Based Protocol to Treat Social Phobia. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2003, 6, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus-Calafell, M.; Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J.; Ribas-Sabaté, J. Improving social behaviour in schizophrenia patients using an integrated virtual reality programme: A case study. In Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine; Wiederhold, B.K., Riva, G., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 181, pp. 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrill, E.D.; Richey, C.A. An assertion inventory for use in assessment and research. Behav. Ther. 1975, 6, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Procter, S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.J.; Rapee, R.M. Post-Event Rumination and Negative Self-Appraisal in Social Phobia Before and After Treatment. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004, 113, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.L.; Rapee, R.; Franklin, J.A. Postevent Rumination and Recall Bias for a Social Performance Event in High and Low Socially Anxious Individuals. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2003, 27, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.Y.; Choi, H.R.; Kwon, S.-M. The Influence of Post-Event Rumination on Social Self-Efficacy & Anticipatory Anxiety. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathus, S.A. A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behav. Ther. 1973, 4, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellings, T.M.; Alden, L.E. Cognitive processes in social anxiety: The effects of self-focus, rumination and anticipatory processing. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, C.; Légeron, P. La peur des autres: Trac, timidité et phobie sociale; Odile Jacob: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, C.J.; King, J.A.; Brewin, C.R. Demonstrating mood repair with a situation-based measure of self-compassion and self-criticism. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 88, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Self-Compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, H.; Kuyken, W.; Wright, K.; Roberts, H.; Brejcha, C.; Karl, A. Soothing Your Heart and Feeling Connected: A New Experimental Paradigm to Study the Benefits of Self-Compassion. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Stanney, K.M. Postural instability induced by virtual reality exposure: Development of a certification protocol. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1996, 8, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rector, N.A.; Bagby, R.M.; Segal, Z.V.; Joffe, R.T.; Levitt, A. Self-Criticism and Dependency in Depressed Patients Treated with Cognitive Therapy or Pharmacotherapy. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2000, 24, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.; Miles, J.; Field, Z. Discovering Statistics Using R; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L. Emotion-Focused Therapy: Theories of Psychotherapy Series; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whelton, W.J.; Greenberg, L.S. Emotion in self-criticism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Liu, Z. Do You Feel the Same as I Do? Differences in Virtual Reality Technology Experience and Acceptance Between Elderly Adults and College Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 573673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felnhofer, A.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Beutl, L.; Hlavacs, H.; Kryspin-Exner, I. Is virtual reality made for men only? Exploring gender differences in the sense of presence. In Proceedings of the Conference of the International Society on Presence Research, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 24–26 October 2012; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

| Virtual Reality + Self-Compassion | Virtual Reality + Self-Criticism | Virtual Reality + Self-Protection | Σ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 28 | 16 | 23 | 67 |

| Scopus | 90 | 46 | 99 | 235 |

| Web of Science | 79 | 34 | 53 | 166 |

| Σ | 197 | 96 | 175 | 468 |

| Reference | Study Type (Defined According to the Purpose of This Systematic Review) | Intervention (Length in Minutes)/Overall VR Exposure in Minutes | VR Exposure in Control Group(s) | VR Intervention Description | VR Type | Sample (age) | Intervention/Control Groups Size | Selected Outcomes (Measure) | Results of Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascone et al., 2020 [45] | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | Psycho-education + VR exposure with embodiment (10)/10 | Yes | Mission to the moon to explore mysterious interactive nebula | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Students with mildly elevated paranoia symptoms (18+) | 12/9 | Self-compassion (brief, state-adapted SCS based on [46]) | Intervention and control groups analyzed independently (within-group). Significant positive change in self-compassion post-psycho-education and VR exposure in intervention group (χ2 = 16.93, p < 0.001). No significant change in self-compassion in control group (χ2 = 3.16, p = 0.206). No effect size reported. |

| Cebolla et al., 2019 [42] (7A) (T2,T3) | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | Virtual body swap/embodiment I. (5) + Self-compassion audio meditation (15) + Virtual body swap/embodiment II. (5–7)/10–12 | No | I. Being in someone else’s body; II. Hugging oneself from third-person perspective | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | University students (18+) | 8/8 | Compassion toward self (positive qualities towards self) (SOFI) | Increase in positive qualities towards self; however, no significant interaction between intervention and control groups, [F(1, 14) = 0.66, p = 0.429, η2p = 0.05]. Large within-group effect size for positive qualities towards self in intervention group (d [95% CI] = −0.82); CI for control group included 0. |

| Cebolla et al., 2019 [42] (7B) (T1,T4) | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | Virtual body swap/embodiment (5) + Self-compassion audio meditation (15) + Virtual body swap/embodiment (5–7) + 2 weeks of voluntary self-compassion audio meditation/10–12 | No | I. Being in someone else’s body; II. Hugging oneself from third-person perspective | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | University students (18+) | 8/8 | Self-compassion as part of self-care behaviors (MSCS) | Increase in self-compassion with no significant interaction effects between intervention and control groups for Self-compassion and Purpose subscale [F(1, 14) = 1.34, p = 0.266, η2p = 0.09]. Large within-group effect size for this subscale in the intervention group (d [95% CI] = −0.77); CI for control group included 0. |

| Falconer et al., 2014 [35] | Longitudinal (between-groups) study; information on group randomization not reported | Psycho-education + Embodiment as an adult (3) + VR scenario I. + Embodiment as a child (3) + VR scenario II./not all durations reported | Yes | I. Speaking to a distressed virtual child; II. Receiving one’s own soothing message from the child’s perspective | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Female undergraduate students with higher levels of self-criticism (18+) | 22/21 | State self-compassion (SCCS), state self-criticism (SCCS) | Self-compassion increased in 1PP group; significant main effect of time [F(1, 41) = 14.33, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.26], with significant interaction between 1PP and 3PP groups [F(1, 41) = 15.87, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.28]. Self-criticism decreased in both 1PP and 3PP groups; main effect of time [F(1, 41) = 42.1, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.51], with no significant interaction between 1PP and 3PP groups [F(1, 41) = 3.46, p = 0.07, η2p = 0.8]. |

| Falconer et al., 2016 [8] | Longitudinal (within-group) study with 4-week follow-up | Psycho-education + 3× once weekly [Embodiment as an adult (2) + VR scenario I. (2) + Embodiment as a child (2) + VR scenario II. (2)]/24 | N/A | I. Speaking to a distressed virtual child; II. Receiving one’s own soothing message from the child’s perspective | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Current major depressive disorder (18+) | 15/- | Self-compassion, self-criticism (SCCS) | Significant linear increase in self-compassion [F(1, 12) = 6.65, p < 0.02, η2p = 0.36] and significant linear decrease in self-criticism [F(1, 12) = 23.41, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.66] between pre, post, and 4-week follow-up. |

| Hur et al., 2021 [47] | Longitudinal (within-group) study | 6× [Introduction & VR meditation (5) + VR exposure (7–8) + VR meditation & psycho-education (3)]/90 | No | Participants introduce themselves in student group meeting. Scenarios vary in difficulty. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Social anxiety disorder (18+) | 21/21 (control group not relevant for selected variable) | Negative post-event ruminations (PERS) | Negative post-event ruminations significantly decreased between pre- and post-measures (Z = −3.32, p < 0.001, r = 0.51). |

| Kim et al., 2020 [48] | Longitudinal (within-group) study | 6× [Introduction & VR meditation + VR exposure + psycho-education]/90 | No | Participants introduce themselves in student group meeting. Scenarios vary in difficulty. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Social anxiety disorder (18+) | 32/33 (control group not relevant for selected variable) | Negative post-event ruminations (PERS) | Negative post-event ruminations significantly decreased after the intervention [F(2.730) = 6.97, p < 0.001]. Effect size not reported. |

| Klinger et al., 2004; 2005 [41,40] | Non-randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | Introduction + 11× [VR assessment and/or VR exposure (20)]/220 | No | Four different social situations causing anxiety. | Non-immersive (PC)/interactive | Outpatients with social phobia (18+) | 18/18 | Assertiveness (RAS, SCIA) | Assertiveness significantly increased in both VR and group CBT conditions; F(1, 34) = 36.30, p < 0.001 for RAS and F(1, 34) = 65.77, p < 0.001 for SCIA/Assertiveness subscale; CBT shows greater improvement for both subscales. No significant interaction effects were found; F(1, 34) = 2.66, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.07 for RAS, and F(1, 34) = 0.81, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.02 for SCIA/Assertiveness subscale. |

| Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021 [49] | Randomized controlled trial with 6-month follow-up | 6× once weekly [Mindfulness meditation (75) + VR meditation (app.7.5)]/46 | No | Observing objects (tree, leaves, lemon, etc.), human figure, walking through a landscape, taking part in a university exam. | Immersive (HMD)/non-interactive | University students (18+) | 70/65/53 | Self-compassion (SCS) | Self-compassion significantly increased from pre-to-post (B = 7.93, p < 0.001, d = 0.94) and from pre- to 6-month follow-up (B = 12.42, p < 0.001, d = 1.47) in VR mindfulness group, compared with relaxation. No significant interaction effect between VR and non-VR mindfulness group; pre-to-post (B = 0.86, p = 0.71, d = 0.1) and pre- to 6-month follow-up (B = −3.11, p = 0.19, d = −0.36). |

| Navarrete et al., 2021 [50] (T2,T3) | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | Embodiment (5) + Embodiment with audio (4.5) + Audio (3)/9.5 | No | Embodying a patient with panic attack disorder and directing compassion towards him. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Healthcare students and professionals (18+) | 21/20 | State self-compassion (VAS-SC, 2 questions), state self-criticism (VAS-SC, one question) | Self-compassion decreased a little in intervention group [t(20) = 0.21, p = 0.838, η2 = 0.00], no significant interaction with control group [F(1, 38) = 0.35, p = 0.556, η2 = 0.00]. Self-criticism decreased in intervention group [t(19) = 1.85, p = 0.079, η2 = 0.15], no significant interaction with control group [F(1, 37) = 0.03, p = 0.868, η2 = 0.00]. |

| O’Gara et al., 2022 [51] | Longitudinal (within-group) study | 3× [VR exposure (10) at least a week apart]/30 | N/A | 360° video of a beach, animated mountain, or animated forest scene, with choice of a male or female guiding voice delivering breathing and CMT exercises | Immersive (HMD)/non-interactive | Cancer patients (18+) | 10/- | Self-compassion (SCS) | No significant changes between baseline, VR1, VR2, and VR3 sessions for any SCS subscales (SK: χ2(3) = 0.733, p = 0.866; SJ: χ2(3) = 2.133, p = 0.545; CH: χ2(3) = 0.976, p = 0.807; IS: χ2(3) = 2.018, p = 0.569; MF: χ2(3) = 5.23, p = 0.156; OI: χ2(3) = 4.417, p = 0.22). No significant changes between baseline and VR3 sessions for any SCS subscale (SK: Z = −1.011, p = 0.312; SJ: Z = −0.978, p = 0.328; CH: Z = −0.224, p = 0.823; IS: Z = −1.261, p = 0.207; MF: Z = −1.605, p = 0.108; OI: Z = −1.43, p = 0.153). Total SCS score and effect size not reported. |

| Park et al., 2011 [52] | Randomized controlled trial | 10× [3× VR role plays, including modeling by therapist and positive or corrective feedback (90)]/duration details not reported | No | Conversation, assertiveness, and emotional expression skills trained in common social situations. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Inpatients with schizophrenia (18+) | 32/31 | Assertiveness (RAS) | Improvements in assertiveness in both VR and non-VR social skills training group; significant time effect, F(1, 62) = 26.17, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.3; and significant time x group interaction, F(1, 62) = 4.96, p = 0.03, η2p = 0.07. VR group shows greater improvement on RAS score. |

| Park & Ogle, 2021 [53] | Longitudinal (within-groups) study | 4× [Body positivity program (120)] + Virtual avatar experience (4–13)/4–13 | No | Presenting anthropometrically accurate avatars of participants themselves in four different contextual backgrounds. | Non-immersive (PC)/interactive | Female undergraduate students with body image concerns (18+) | 9/9 (control group not relevant for selected variable) | Self-compassion (SCS-SF) | Purpose of control group unclear. Repeated-measures ANOVA (most likely for experimental group data) shows significant improvements in self-compassion between baseline and post-VR (p = 0.000) and between pre-VR and post-VR (p = 0.041). No inferential statistics or effect size reported. |

| Price & Anderson, 2011 [54] | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | 8× [VR exposure]/not reported | No | Challenging public speaking situations, such as classroom or auditorium. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Individuals diagnosed with social anxiety disorder (18+) | 32/33/25 | Ruminations (RQ) | VR exposure (β = −8.82, p < 0.01) and group CBT (β = −9.85, p < 0.01) both significantly better than waiting list controls. VR and CBT together had a large effect size compared with waiting list (33% of the variance at post-intervention). After controlling for pre-intervention scores, no significant difference between group CBT and VR at post-intervention (β = 0.62, p = 0.62). |

| Riva et al., 2001 [11] | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | 7× once weekly [VR exposure (50)] + low-calorie diet + physical training (minimum twice 30 min walk a week)/350 | No | Exposure to environments, potentially eliciting abnormal eating behaviors. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Female patients with overweight issues (18+) | 28 participants in total (estimated as 14/14) | Assertiveness (AI) | Significant improvements in ability to engage in anxiety-provoking behaviors (p = 0.014) within intervention group, and significant improvements in ability to engage in anxiety-provoking behaviors in intervention group compared with control group (p = 0.000). No other inferential statistics or effect size reported. |

| Riva et al., 2002 [55] | Randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | 7× once weekly [VR exposure (50)] + low-calorie diet + physical training (minimum twice 30 min walk a week)/350 | No | Exposure to environments potentially eliciting abnormal eating behaviors. | Immersive (HMD)/interactive | Female patients with binge eating disorder (18+) | 20 participants in total (estimated as 10/10) | Assertiveness (AI) | Significant improvements in ability to engage in anxiety-provoking behaviors (p = 0.038) within intervention group and non-significant improvements in ability to engage in anxiety-provoking behaviors in intervention group compared with control group (p = 0.063). No other inferential statistics and effect size reported. |

| Roy et al., 2003 [56] | Non-randomized, longitudinal (between-groups) study | Introduction + 11× [VR assessment and/or VR exposure (20)]/220 | No | Four different social situations causing anxiety. | Non-immersive (PC)/interactive | Social phobia (18+) | 4/6 | Assertiveness (RAS) | Based on descriptive statistics, assertiveness increased in both VR and group CBT conditions. No inferential statistics, significance levels, or effect size reported. |

| Rus-Calafell et al., 2012 [57] | Case study | 16× [Content introduction (30) + VR exposure (30)]/480 | N/A | Exposure to common daily situations, such as going to a shop or dealing with an angry security guard. | Non-immersive (PC + 3D glasses + headphones)/interactive | Schizophrenia outpatient (18+) | 1/- | Assertiveness (AI, number of assertive behaviors observed) | Improvements in ability to engage in anxiety-provoking behaviors pre- and post-intervention (no inferential statistics reported). Significant increase in assertive behaviors pre- to post-intervention (Z = −3.28, p < 0.05). No effect size reported. |

| Rus-Calafell et al., 2014 [15] | Longitudinal (within-group) study with 4-month follow-up | 16× [Content introduction (30) + VR exposure (30)]/480 | N/A | Exposure to common daily situations, such as going to a shop or dealing with an angry security guard. | Non- immersive (PC + 3D glasses + headphones)/interactive | Schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder outpatients (18+) | 12/- | Assertiveness (AI, number of assertive behaviors observed) | Significant improvements in ability to engage in anxiety-provoking behaviors pre- and post- a 4-month follow-up, with large effect [F(2, 22) = 70.79, p < 0.01, d = 0.87]. Same results observed for number of assertive behaviors observed [F (3, 33) = 139.76, p < 0.01]; no effect size reported. |

| Random Sequence Generation/Allocation Concealment(Selection Bias) | Blinding of Participants and Personnel (Performance Bias) | Blinding of Outcome Assessment (Detection Bias) | Incomplete Outcome Data Addressed (Attrition Bias) | Selective Reporting (Reporting Bias) | Other Biases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascone et al. (2020) [45] | U | H | H | L | U | H |