LGBTQIA+ Adolescents’ Perceptions of Gender Tailoring and Portrayal in a Virtual-Reality-Based Alcohol-Prevention Tool: A Qualitative Interview Study and Thematic Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. The VR Simulation Virtual LimitLab

2.3. Inclusion Criteria and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection and Processing

- General perceptions of the simulation;

- The perception of gender aspects;

- The assessment of current tailoring and gender portrayal;

- Potentially important categories other than gender; and

- Suggestions for improvement and further development.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Familiarisation with the dataset: Initially, interview transcripts were re-read, re-heard, and corrected where necessary, and first ideas were noted down. Field notes taken after each interview were also re-read. This step was performed by C.P.

- Generating initial codes: C.P. chose three of “the richest” interviews (in terms of the depth of the assessed data and the interview time). Transcripts from these three interviews were inductively coded in parallel by two researchers (i.e., C.P. and K.H.) by broadly marking text passages while saving context, contradictions, and double occupancy in the passages for later discussion. Subsequent discussion was used to seek collaboration when reflecting on the understanding of the transcripts and the initial codes rather than to seek consensus on a final codebook [45]. After discussion of each of these three interviews, contradictions and open questions remained. The remaining 13 interviews were coded by C.P. exclusively. The subsequent steps were performed by C.P. in a later discussion along with K.H. MAXQDA software (2022) (VERBI Software GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used for computer-assisted organisation.

- Generating initial themes: After all data had been coded, theme candidates were aggregated by organising codes on a higher, more abstract level in terms of shared topics, strong relation, and content coherency. Initial, different thematic maps were developed and discussed in order to illustrate how the initial themes and code candidates were related to one another.

- Developing themes: The initial themes were reviewed by checking for internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity in relation to the coded extracts. Therefore, coded extracts were re-read, some passages were re-coded, and some codes were combined or split, when necessary. A theme that did not address the research question was removed (general VR experiences), and code candidates were revised and combined. This step was performed by C.P. and led to a revised thematic map.

- Defining and naming themes: Definitions of themes were generated, and relationships between preliminary themes as well as between individual codes were checked. The generated revised thematic map was used to analytically undergo the coded extracts, and the adaption led to a finalised thematic map. Until this phase, discussion among the researchers (i.e., C.P. and K.H.) and reflection with an external qualitative research group (i.e., Qualitative Forschungswerkstatt, Charité) had been used to reflect on and refine the analysis and interpretation in order to meet the quality criterion of inter-subject comprehensibility [37].

- Writing the report: In order to prepare the article, themes and codes were ordered in a list. This order did not represent a hierarchy; rather, it represented a logical order that enabled the researchers to comprehensibly lead through the results. This list was then filled in with all corresponding statements for each code and sub-code in order to serve as a basis for writing the present manuscript.

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

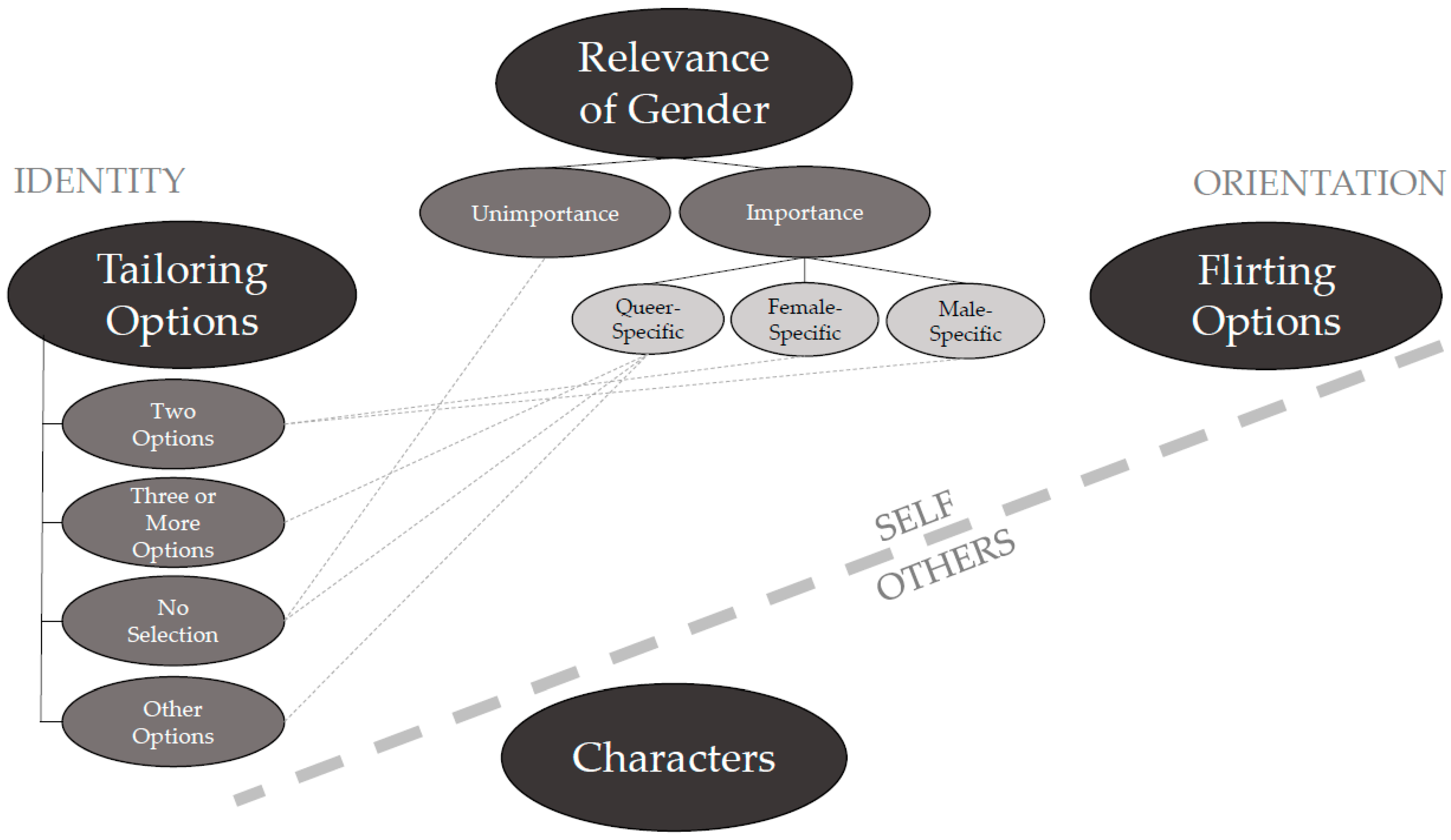

3.2. Overview of the Thematic Map

- Relevance of gender;

- Tailoring options;

- Flirting options; and

- Characters.

3.3. Description of Themes

3.3.1. Theme 1: Relevance of Gender

“That’s why I think the avatar selection is so unimportant. You wouldn’t need to pre-select [an avatar gender] because it’s more important how I feel right now, how I’m doing at the party, and how I see things through my eyes rather than which category I belong to”.(G)

“In real life, we all don’t experience the same night at the same party. And I think that when you simulate something like that, I think it’s good to pay attention to what different people experience”.(B)

“I think it’s a good idea to combine [alcohol prevention and the prevention of sexual harassment] because many things happen under the influence of alcohol and drugs that you don’t want to happen. Also, from my own experience, I can say a lot about what can happen, again and again, at mainstream parties and everywhere else. At my [queer] parties, unfortunately, that is also an issue, especially under the influence of alcohol”.(G)

“Well, there [in general] is a lot of hostility. And at a typical house party, I would definitely expect some of that hostility. And if you want it [the simulation] to be close to reality, that [hostility] would have to be included”.(I)

3.3.2. Theme 2: Tailoring Options

“Maybe ‘diverse’ [should be used] because it’s acknowledged by law as the third gender. But, of course, that’s not true because there are more than three genders”.(J)

“Because if you differentiate between the scenes, it leads to stereotypes. And if, for example, you distinguish between… yeah, if you choose the male avatar, you get into a fight, and the girls end up on the toilet throwing up or something, then I think you’re really reinforcing stereotypes. So, I think it [the simulation] should be kept neutral”.(L)

- Building one’s own avatar with an individual look (which was considered exciting but overly complicated for a short simulation if this option did not have consequences within the scenes);

- Entering the user’s exact height and weight in order to personalise the BAC to a more precise body mass index (which was considered more realistic but a sensitive topic);

- Possibly including other relevant identity categories (which was considered irrelevant to the avatar choice in context of this simulation), and most prominently;

- Inclusion of a queer party scenario in the simulation.

“But also, the same game doesn’t necessarily work for everyone. So, we cannot assume that a cis white male person would feel super safe at a BIPoC [i.e., Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour] queer party. I would also find it okay that it’s not like that. That’s also allowed to be, because we experience things much more often the other way around. Yeah, it would be interesting to have more options and to be able to choose a party”.(F)

3.3.3. Theme 3: Flirting Options

“I just noticed that another male character asked me if I wanted to dance when I was playing as the male character. That’s really good because that’s so… I didn’t notice it at first because it was so normal. And that was really good”.(O)

3.3.4. Theme 4: Characters

“Me, as a non-German-looking person, you are somehow used to it [the lack of representation]. Basically, you already have it in your head as a standard that everyone is white. You don’t even pay attention to it anymore […]. So, the way [the simulation] was didn’t bother me. But it would also be a bonus if it [the simulation] were more diverse. And, of course, it’s always good to re-evaluate things. That is important. So that this standard way of thinking is not shaped. You can’t do it wrong, but better. And I would find it [the simulation] better with with more diversity. It would be a plus. Exactly. If there were more diversity, you might feel a little more seen. Not totally consciously, but perhaps subconsciously”.(O)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Representing diversity (both in terms of gender and otherwise) among the characters;

- Inclusion of sexual diversity via open flirting options (i.e., not only homosexual options, but also bisexual and aromantic/asexual options); and

- Conducting further research on whether and how to combine and address gender-specific experiences (e.g., hostility toward LGBTQIA+ adolescents) within alcohol-prevention interventions.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hsieh, N.; Shuster, S.M. Health and health care of sexual and gender minorities. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondeel, K.; Say, L.; Chou, D.; Toskin, I.; Khosla, R.; Scolaro, E.; Temmerman, M. Evidence and knowledge gaps on the disease burden in sexual and gender minorities: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; Cariola, L.A. LGBTQI+ Youth and Mental Health: A systematic review of qualitative research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2020, 5, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöge, K.; Dennert, G.; Koppe, U.; Güldenring, A.; Matthigack, E.B.; Rommel, A. Die gesundheitliche Lage von lesbischen, schwulen, bisexuellen sowie trans- und intergeschlechtlichen Menschen [The health situation of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans- and intersex people]. J. Health Monit. 2020, 5, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprowski, D.; Fischer, M.; Chen, X.; de Vries, L.; Kroh, M.; Kühne, S.; Richter, D.; Zindel, Z. LGBTQI* people in germany face staggering health disparities. DIW Wkly. Rep. 2021, 11, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Greytak, E.A.; Parsons, J.T.; Ybarra, M.L. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: Disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPAD Group. ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: http://www.espad.org/espad-report-2019#downloadReport (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Kuntz, B.; Lange, C.; Lampert, T. Alkoholkonsum bei Jugendlichen—Aktuelle Ergebnisse und Trends [Alcohol consumption among young people—Current results and trends]. Gesundh. Kompakt 2015, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Youth-Centred Digital Health Interventions: A Framework for Planning, Developing and Implementing Solutions with and for Young People. Geneva. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336223/9789240011717-eng.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Park, M.J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, U.; Na, E.J.; Jeon, H.J. A Literature overview of virtual reality (VR) in treatment of psychiatric disorders: Recent advances and limitations. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Li, Y.I.; Hu, W.P.; Huang, C.C.; Du, Y.C. A scoping review of the efficacy of virtual reality and exergaming on patients of musculoskeletal system disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.; Olivas, G.; Steele, P.; Smith, C.; Bailey, L. Exploring pedagogical foundations of existing virtual reality educational applications: A content analysis study. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2018, 46, 414–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.Q.; Leng, Y.F.; Ge, J.F.; Wang, D.W.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z.L. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Nursing Education: Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, F.; Shi, D.; Shi, J.; Tian, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q. Application of virtual reality technology in clinical medicine. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3867–3880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durl, J.; Dietrich, T.; Pang, B.; Potter, L.-E.; Carter, L. Utilising virtual reality in alcohol studies: A systematic review. Health Educ. J. 2018, 77, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu-Au, E.; Lee, J. Virtual reality in education: A tool for learning in the experience age. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2018, 4, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prediger, C.; Hrynyschyn, R.; Iepan, I.; Stock, C. Adolescents’ perceptions of gender aspects in a virtual-reality-based alcohol-prevention tool: A focus group study. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022, 19, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Kubacki, K.; Durl, J.; Gullo, M.; Arli, D.; Connor, J. Virtual reality in social marketing: A process evaluation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallentin-Holbech, L.; Guldager, J.D.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Majgaard, G.; Lyk, P.; Stock, C. Co-creating a virtual alcohol prevention simulation with young people. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 17, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldager, J.D.; Kjær, S.L.; Lyk, P.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Majgaard, G.; Stock, C. User experiences with a virtual alcohol prevention simulation for Danish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 17, 6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldager, J.D.; Kjær, S.L.; Grittner, U.; Stock, C. Efficacy of the virtual reality intervention VR FestLab on alcohol refusal self-efficacy: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022, 19, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, B.; Rauschner, A. Avatar. In Game Studies; Beil, B., Hensel, T., Rauscher, A., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- Dir, A.L.; Bell, R.L.; Adams, Z.W.; Hulvershorn, L.A. Gender differences in risk factors for adolescent binge drinking and implications for intervention and prevention. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, D.J.; Muslić, L.; Krašić, S.; Markelić, M.; Franelić, I.P.; Milanović, S.M. Gender differences in the prediction of alcohol intoxication among adolescents. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 56, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchini, M. Reinforcing and reproducing stereotypes? Ethical considerations when doing research on stereotypes and stereotyped reasoning. Societies 2019, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienaar, K.; Murphy, D.A.; Race, K.; Lea, T. Problematising LGBTIQ drug use, governing sexuality and gender: A critical analysis of LGBTIQ health policy in Australia. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 55, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbey, D.; Morgan, H.; Lin, A.; Perry, Y. Effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of digital health interventions for LGBTIQ+ young people: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, B.; Klocke, U.; Hoffmann, L.-C. Einstellungen Gegenüber Lesbischen, Schwulen und Bisexuellen Menschen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse einer Bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Umfrage [Attitudes towards Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual People in Germany. Results of a Population-Representative Survey]; Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/Umfragen/umfrage_einstellungen_geg_lesb_schwulen_und_bisex_menschen_de.html (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Pöge, K.; Rommel, A.; Starker, A.; Prütz, F.; Tolksdorf, K.; Öztürk, I.; Strasser, S.; Born, S.; Saß, A.C. Survey of sex/gender diversity in the GEDA 2019/2020-EHIS study—objectives, procedure and experiences. J. Health Monit. 2022, 7, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M. Geschlechtersensible Gestaltung digitaler Gesundheitsförderung [Gender-sensitive design of digital health promotion]. Präv. Gesundh. 2021, 16, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.W.; Stefanick, M.L.; Peragine, D.; Neilands, T.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pilote, L.; Prochaska, J.J.; Cullen, M.R.; Einstein, G.; Klinge, I.; et al. Gender-related variables for health research. Biol. Sex Differ. 2021, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Repta, R. Sex and gender: Beyond the binaries. In Designing and Conducting Gender, Sex, & Health Research; Oliffe, J.L., Greaves, L., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wagaman, M.A. Self-definition as resistance: Understanding identities among LGBTQ emerging adults. J. LGBT Youth 2016, 13, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, C.M.; Gower, A.L.; Brown, C.; Wood, B.; Eisenberg, M.E. Perceptions of sexual orientation and gender identity minority adolescents about labels. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 42, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogette, T. Exit Rasicm. Rassismuskritisch Denken Lernen; Unrast-Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2020; Volume 9, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Steinke, I. Quality criteria in qualitative research. In A Companion to Qualitative Research; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 21, pp. 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyk, P.; Majgaard, G.; Vallentin-Holbech, L.; Guldager, J.D.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Stock, C. Co-designing and learning in virtual reality. Development of tool for alcohol resistance training. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2020, 18, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, S.; Buder, J. Virtuelle Realität und E-Learning. 2006. Available online: https://www.e-teaching.org/didaktik/gestaltung/vr/vr.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Helfferich, C. Die Qualität Qualitativer Daten. Manual für die Durchführung Qualitativer Interviews [The Quality of Qualitative Data. Manual for Conducting Qualitative Interviews]; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, A.-L.; Egenberger, V.; Supik, L. Erhebung von Antidiskriminierungsdaten in Repräsentativen Wiederholungsbefragungen Bestandsaufnahme und Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten [Collection of Anti-Discrimination Data in Routinely Representative Surveys. Up-to-Date Inventory and Development Opportunities]; Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/Expertisen/erhebung_von_antidiskr_daten_in_repr_wiederholungsbefragungen.pdf;jsessionid=DA89E5685FC0012A7F476D9336A167D5.intranet241?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2020, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomillion, S.C.; Giuliano, T.A. The influence of media role models on gay, lesbian, and bisexual identity. J. Homosex. 2011, 58, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInroy, L.B.; Craig, S.L. Perspectives of LGBTQ emerging adults on the depiction and impact of LGBTQ media representation. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 20, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, J.N. Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowleg, L. Evolving intersectionality within public health: From analysis to action. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.J.; Veloso, P.G.; Araújo, M.; de Almeida, R.S.; Correia, A.; Pereira, J.; Queiros, C.; Pimenta, R.; Pereira, A.S.; Silva, C.F. Impact of a virtual reality-based simulation on empathy and attitudes toward schizophrenia. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 814984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.H.H.; Chan, S.H.M.; Tan, Y.C. Perspective-taking in virtual reality and reduction of biases against minorities. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, K.M.; Espelage, D.L.; Merrin, G.J.; Valido, A.; Heinhorst, J.; Joyce, M. Evaluation of a virtual reality enhanced bullying prevention curriculum pilot trial. J. Adolesc. 2019, 71, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sora-Domenjó, C. Disrupting the “empathy machine”: The power and perils of virtual reality in addressing social issues. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 814565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byron, P. ‘Apps are cool but generally pretty pointless’: LGBTIQ+ young people’s mental health app ambivalence. Media Int. Aust. 2019, 171, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H.; O’Donovan, A.; Almeida, R.; Lin, A.; Perry, Y. The role of the avatar in gaming for trans and gender diverse young people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draude, C.; Maaß, S. Making IT work: Integrating gender research in computing through a process model. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Gender & IT, Heilbronn, Germany, 14–15 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Age | Gender Identity | Sexual Orientation | Type of School | Ethnical /Cultural Self- Description | Are You Usually Perceived as a white German? | Religion | Experience with Virtual Reality | Experience with Drinking Alcohol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 Years Mean: 16.7 years SD 1: 1.5 | non-binary non-binary non-binary non-binary/genderqueer non-binary/diverse female female female cisgender women women/she women man male trans man trans man n. a. 2 | queer/unlabelled queer aro/ace 3 bisexual/asexual bisexual bisexual bi pansexual pansexual lesbian no label no label in general I do not know trans n. a. n. a. | upper-level secondary school or grammar school (n = 12) integrated comprehensive secondary school (n = 2) vocational school (n = 1) school for children with learning difficulties (n = 1) | German (n = 8) n. a. (n = 4) white (n = 2) Turkish (n = 1) person of colour (n = 1) | yes (n = 11) no (n = 4) I do not know (n = 1) | none (n = 10) Muslim (n = 3) Catholic (n = 2) Protes-tant (n = 1) | yes (n = 12) no (n = 2) I do not know (n = 2) | yes (n = 14) no (n = 2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prediger, C.; Heinrichs, K.; Tezcan-Güntekin, H.; Stadler, G.; Pilz González, L.; Lyk, P.; Majgaard, G.; Stock, C. LGBTQIA+ Adolescents’ Perceptions of Gender Tailoring and Portrayal in a Virtual-Reality-Based Alcohol-Prevention Tool: A Qualitative Interview Study and Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042784

Prediger C, Heinrichs K, Tezcan-Güntekin H, Stadler G, Pilz González L, Lyk P, Majgaard G, Stock C. LGBTQIA+ Adolescents’ Perceptions of Gender Tailoring and Portrayal in a Virtual-Reality-Based Alcohol-Prevention Tool: A Qualitative Interview Study and Thematic Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042784

Chicago/Turabian StylePrediger, Christina, Katherina Heinrichs, Hürrem Tezcan-Güntekin, Gertraud Stadler, Laura Pilz González, Patricia Lyk, Gunver Majgaard, and Christiane Stock. 2023. "LGBTQIA+ Adolescents’ Perceptions of Gender Tailoring and Portrayal in a Virtual-Reality-Based Alcohol-Prevention Tool: A Qualitative Interview Study and Thematic Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042784

APA StylePrediger, C., Heinrichs, K., Tezcan-Güntekin, H., Stadler, G., Pilz González, L., Lyk, P., Majgaard, G., & Stock, C. (2023). LGBTQIA+ Adolescents’ Perceptions of Gender Tailoring and Portrayal in a Virtual-Reality-Based Alcohol-Prevention Tool: A Qualitative Interview Study and Thematic Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042784