The Influence of Social Media on the Perception of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Content Analysis of Public Discourse on YouTube Videos

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

1.2. Stigmatization towards ASD

1.3. The Media’s Influence on Public Perception

1.4. YouTube as a Platform for ASD Awareness

1.5. Aim

2. Methodology and Framework

2.1. Key Search Words

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection Procedure

2.4. Basic Descriptors and Attributes

2.5. Identification of Themes

2.6. Identification of Sentiment

2.7. Identification of Damaging Language and Stigmatization

- People with autism do not want friends;

- People with autism cannot feel or express any emotion—happy or sad;

- People with autism cannot understand the emotions of others;

- People with autism are intellectually disabled;

- People who display qualities that may be typical of a person with autism are just odd and will grow out of it;

- Autism only affects children;

- Autism is just a brain disorder.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Descriptors for 2019 and 2022 Videos

3.2. Attributes for Videos Selected

4. Themes in 2019 Videos

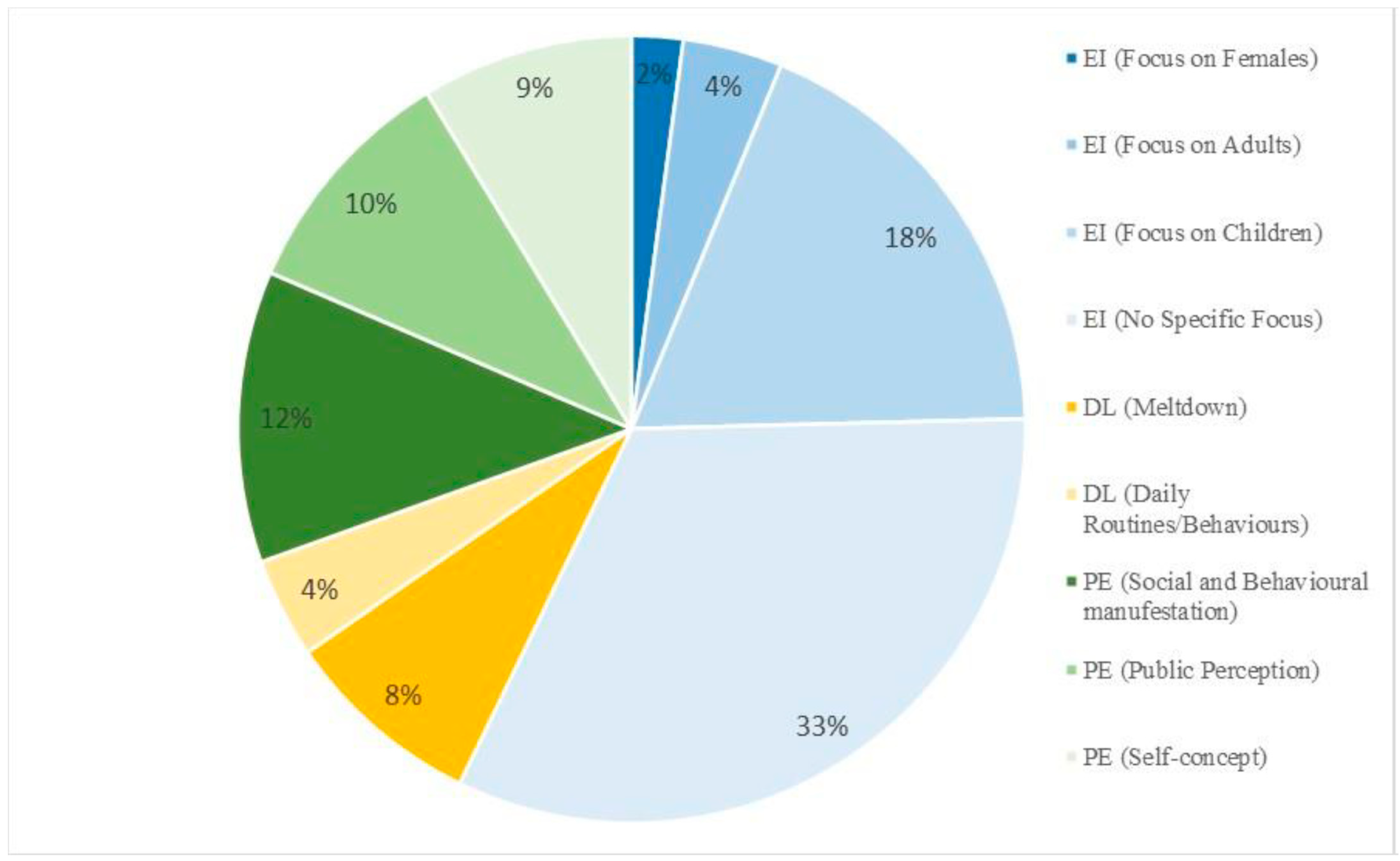

- Providing Educational Information (57.2%): The content in videos was constructed to provide educational information on ASD. This included a discussion of ASD etiology, social and behavioural manifestations, diagnosis, and interventions. This category can be further classified by the demographic of the people with ASD the video focused on:

- 1.1.

- Specific focus on children (18.4%): Videos discussing social and behavioural manifestations a child might exhibit, for example, self-stimulatory behaviours, such as hand flapping, grunting, or excessive blinking. Videos with this theme also included animations to help children learn about ASD.

- 1.2.

- Specific focus on adults (4.1%): Videos discussing topics such as communication difficulties and impairments in abstract thought that might persist into adulthood, in addition to addressing how to attain a late diagnosis.

- 1.3.

- Specific focus on females (2.1%): Videos underscore ASD characteristics in females, issues with the lack of female ASD research, and how women are being misdiagnosed with other conditions such as bipolar disorder.

- 1.4.

- No specific age or sex focus (32.6%): Content in these videos is generic. In some videos, the presenter does not direct ASD-related information to a specific demographic. In others, the presenter may highlight attributes of ASD in males, females, children, and adults.

- Discussion of Personal Experiences (30.5%): Videos with this theme have individuals with ASD or their significant others (child, parent, coworker, friend, etc.) share their own personal experience of having ASD or taking care of or interacting with a person with ASD. Three subthemes emanated from this category:

- 2.1.

- Personal Social and Behavioural Manifestations (12.0%): Video presenters provide background information on the social and behavioural manifestations that they or their significant other exhibit. They also elaborate on how these neurological differences have affected their lives; for example, some individuals note that it made social interaction more difficult. Further discussions included their age of diagnosis and interventions they have used.

- 2.2.

- Public Perception (9.8%): Video presenters gave an account on the things people have said to them or how their friends, family, and peers have treated them or a significant other with ASD. For example, people say “you do not look autistic”. Some presenters also specifically highlight incidences of bullying from their peers, as well as others misunderstanding their behaviour and thinking they are “rude” or “weird”.

- 2.3.

- Self Concept (8.7%): Individuals in the video discuss how they felt about having ASD before and after a diagnosis. Individuals discussed feeling awkward or like they were not normal. Some expressed feeling lonely and self-esteem issues, such as not feeling like they were beautiful. In addition, it was mentioned how an actual diagnosis brought relief and comfort to their life.

- Daily Life Videos (12.3%): Videos with this theme included vlogs of people showcasing activities performed during their day. This category excludes videos that have presenters displaying and explaining behaviours in order to educate their audience. This theme is broken down into two subthemes:

- 3.1.

- Completing daily routines (4.1%): These videos display individuals completing day-to-day activities, such as getting ready for school, travelling, and attending doctors’ appointments.

- 3.2.

- Meltdowns (8.2%): These videos specifically highlight an incident during the day. They display an individual with ASD having a “meltdown”. These videos showcase self-injurious behaviour and uncontrolled screaming or crying.

5. Themes in Comments

6. Sentiment of Videos and Comments

7. Use of Damaging Language and Stigmatization for 2019 Retrievals

8. Discussion

8.1. Video Attributes: Major Findings and Implications

8.2. YouTube Videos as an Educational Resource

8.3. Benefits of Sharing Personal Stories in Videos and Comments

8.4. “Mixed” Messages Provide a Dynamic View

8.5. Severe Autism and Negative Comments

8.6. Stigmatization and Person-First Language

8.7. Limitations

8.8. Future Studies

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lai, M.V.; Baron-Cohen, S. Autism. Lancet 2014, 383, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scattone, D.; Tingstrom, D.H.; Wilczynski, S.M. Increasing Appropriate Social Interactions of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders Using Social StoriesTM. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2006, 21, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, K.; Couteur, A.L. Diagnosing autism. Paediatr. Child Health 2013, 23, 5–10. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/yt/about/press/ (accessed on 30 April 2019). [CrossRef]

- Kopetz, P.; Endowed, D.L. Autism Worldwide: Prevalence, Perceptions, Acceptance, Action. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaidez, V.; Fernandez y Garcia, E.; Wang, L.W.; Angkustsiri, K.; Krakowiak, P.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Hansen, R.L. Comparison of maternal beliefs about causes of autism spectrum disorder and association with utilization of services and treatments. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinan, Z.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global Prevalence of Autism: A Systematic Review Update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; Arlington, V.A., Ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin, M.S.; Maenner, M.J.; Christensen, D.; Daniels, J.; Fitzgerald, R.; Imm, P.; Lee, L.C.; Schieve, L.A.; Van Naarden Braun, L.; Wingate, M.S.; et al. Autism spectrum disorder among US children (2002–2010): Socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Risi, S.; Dilavore, P.; Shulman, C.; Thurm, A.; Pickles, A. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avni, E.; Ben-Itzchak, E.; Zachor, D.A. The Presence of Comorbid ADHD and Anxiety Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Clinical Presentation and Predictors. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R. Autism. Lancet 2016, 387, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton. Clinical Diagnoses Exacerbate Stigma and Improve Self-Discovery According to People with Autism. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2014, 12, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samari, E.; Seow, E.; Chua, B.Y.; Ong, H.L.; Abdin, E.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Stigma towards people with mental disorders: Perspectives of nursing students. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Brooks, P.; Someki, F.; Obeid, R.; Shane-Simpson, C.; Kapp, S.; Smith, D. Changing college students’ conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2553–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordahl-Hansen, A.; Tøndevold, M.; Fletcher-Watson, S. Mental health on screen: A DSM-5 dissection of portrayals of autism spectrum disorders in film and TV. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, K.; Chaudhury, S.; Bhat, P.S.; Mujawar, S. Media and mental health. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2018, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl-Hansen, A. Atypical: A typical portrayal of autism? Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, E.K.; Shorter, J.D. Social Networking and the Exchange of Information. Issues Inf. Syst. 2014, 15, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bellon-Harn, M.L.; Manchaiah, V.; Morris, L.R. A cross-sectional descriptive analysis of portrayal of autism spectrum disorders in YouTube videos: A short report. Autism 2020, 24, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlow, C.; O’Dell, L.; Rosqvist, H.B. COMMENTARY: Challenging Representations of Autism—Exploring Possibilities for Broadcasting the Self on YouTube. J. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 19, 90–95. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=90487611&site=ehost-liv (accessed on 30 April 2019).

- Khan, M.L. Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, B.E. Broadcasting disability: An exploration of the educational potential of a video sharing web site. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2008, 23, 1–13. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/docview/228523871?accountid=14701 (accessed on 30 April 2019). [CrossRef]

- Azer, S.A.; Bokhari, R.A.; AlSaleh, G.S.; Alabdulaaly, M.M.; Ateeq, K.I.; Guerrero, A.P.S.; Azer, S. Experience of parents of children with autism on YouTube: Are there educationally useful videos? Inform. Health Soc. Care 2018, 43, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, L.A.; Konkle, A.T. The Representation of Depression in Canadian Print News. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2016, 35, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbitter, K.; Buckle, K.L.; Ellis, C.; Dekker, M. Autistic Self-Advocacy and the Neurodiversity Movement: Implications for Autism Early Intervention Research and Practice. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, J.; Charron, V.; Konkle, A.T.M. Feeling the void: Lack of support for isolation and sleep difficulties in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed by Twitter data analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantaye, A.W.; Konkle, A.T.M. Social media representation of female genital cutting: A YouTube analysis. Women’s Health 2020, 16, 1745506520949732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, A. The Phenomenology of the Social World; Walsh, G.; Lehnert, F., Translators; North Western University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, G.; Begley, C. Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiazek, T.B.; Peer, L.; Lessard, K. User engagement with online news: Conceptualizing interactivity and exploring the relationship between online news videos and user comments. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, A.; Ruthven, I.; McMenemy, D. A classification scheme for content analyses of YouTube video comments. J. Doc. 2013, 69, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfoushi, O.; Hasan, D.; Obiedat, R. Sentiment analysis algorithms through azure machine learning: Analysis and comparison. Modern Appl. Sci. 2018, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, L.; Hattersley, C.; Molins, B.; Buckley, C.; Povey, C.; Pellicano, E. Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism 2016, 20, 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomes, R.; Hull, L.; Mandy, W.P.L. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.R.; Childs, A.W.; Richards, M.; Robins, D.L. Race influences parent report of concerns about symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2019, 23, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, D.S.; Wiggins, L.D.; Carpenter, L.A.; Daniels, J.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Durkin, M.S.; Kirby, R.S. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 99, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.H.; Kreider, C.M.; Brasher, S.N.; Ansell, M. Clinical impact of early diagnosis of autism on the prognosis and parent-child relationships. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, V.A.; Daniels, J.; Duda, M.; Deluca, T.F.; D’Angelo, O.; Tamburello, J.; Wall, D.P. The Potential of Accelerating Early Detection of Autism through Content Analysis of YouTube Videos. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollia, B.; Kamowski-Shakibai, M.; Basch, C.; Clark, A. Sources and content of popular online videos about autism spectrum disorders. Health Promot. Perspect. 2017, 7, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, S.; Osborne, L.A.; Reed, P. Personal experiences disclosed by parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A YouTube analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 64, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, J.A.; Grande, S.W.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Elwyn, G. Naturally Occurring Peer Support through Social Media: The Experiences of Individuals with Severe Mental Illness Using YouTube. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernandez, S.M. The autism activist: With a single YouTube video, Alex 16, has helped thousands of teens understand a complex disorder.(CHOICES CHANGEMAKERS). Scholast. Choices 2016, 31, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Broadcasters. (n.d.). Recommended Guidelines on Language and Terminology—PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES. Available online: https://disability-hub.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Recommended-Guidelines-on-Language-and-Terminology-Persons-with-Disabilities_A-Manual-for-News-Professionals.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2019).

| Age Category of Individual with ASD | (%) |

| Child | 48.8 |

| Adult | 51.2 |

| Sex of Individual with ASD | (%) |

| Male | 62.8 |

| Female | 37.2 |

| Race of Individual with ASD | (%) |

| White | 86.1 |

| Black | 9.3 |

| Asian | 2.3 |

| Other | 2.3 |

| Percentage of Videos in Different YouTube Categories | (%) |

|---|---|

| Nonprofits and Activism | 10 |

| Education | 26 |

| People and Blogs | 42 |

| Science and Technology | 4 |

| Film and Animation | 2 |

| Gaming | 2 |

| Entertainment | 6 |

| News and Politics | 4 |

| Comedy | 2 |

| How to and Style | 2 |

| Theme or Subtheme | Description | Example Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Anecdote | A comment containing a story about a commenter’s personal experience. | |

| Social and Behavioural Manifestations | A comment that shares the ASD-related social and behavioural manifestations of the writer or the writer’s significant other. | “I have Asperger’s and although I am a little socially awkward I’m quite extroverted which makes it hard to spot”. |

| Public Perception | A comment that provides an account of how the writer or their significant other might have been viewed or treated by others. | “People bully me at school. They say I’m weird because I’ll randomly zone out during class. I try to talk to them but they just say look at me then I’ll talk to you, and when I do look at them they tell me to stop staring at them”. |

| Self-Concept | A comment that provides an account of the writer’s feelings about themselves, including their self-image and issues with self-esteem. | “Having Asperger’s sucks. I feel like I’m a different species from the people around me”. |

| Expression of Personal Feelings | A comment in which the writer expresses their personal feelings, emotional response, or opinions/perspectives. | |

| Positive Sentiments | A comment that expresses the writer’s positive beliefs and attitudes towards ASD. | “People I have met that have autism are some of the most kind hearted empathetic and genuine humans”. |

| Negative Sentiments | A comment that expresses the writer’s negative beliefs and attitudes towards ASD. | “I would not want to have a child with autism”. |

| View on Stereotypes or Misconceptions | Comments that express a writer’s view on stereotypes or misconceptions held by society and perpetuated by the media or other information channels. | “I hate how the only autism portrayed in the media is the aesthetic kind where they turn out to be geniuses no one knows about severe autism it kills me”. |

| View on ASD Characteristics | Comments that express a writer’s view on the epidemiology of ASD, associated behaviours, interventions, etc. | “I don’t think it’s more common in boys. Because girls tend to hide it more often which probably means there are loads of girls out there with autism including me”. |

| Reaction to Video Content | Comments expressing a writer’s immediate reaction and feelings toward the information in a video or the way the creator presents it. | |

| Agreeing with or Approving of Creator Content | A comment that expresses agreement, satisfaction, or gratitude towards the video content. | “This was the best way to show neurotypical people autism I’ve ever seen. This is wonderful. Thank you”. |

| Disagreeing with or Disapproving of Creator Content | A comment that expresses disagreement or condemnation of video content. | “I don’t like this one bit. Those children are not autistic they may just have different personalities”. |

| Miscellaneous Exclamations | Comments with weak or no correlation to ASD-related content. This category also includes summarizing or directly quoting something in the video, making video requests, and random off-topic jokes, statements, or questions. | “Well now I have a crush on the girl in the maroon shirt”. |

| Theme or Subtheme | Description | Example Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Anecdote | A comment containing a story about a commenter’s personal experience. | “The main problem with being autistic in today’s society is that the world just isn’t built for us”. This destroys me every day. |

| Social and Behavioural Manifestations | A comment that shares the ASD-related social and behavioural manifestations of the writer or the writer’s significant other. | “The inner conflict is maddening. All the things that make me feel most alive quickly burn me out…” |

| Public Perception | A comment that gives an account of how the writer or their significant other might have been viewed or treated by others. | “I’ve been hurt so many times by people I thought would never hurt me. Now that I’m 37 and have been crushed over and over with another one coming soon, I would just assume never get involved with another person”. |

| Self-Concept | A comment that gives an account of the writer’s feelings about themselves, including their self-image and issues with self-esteem. | “Nope, I’ve learnt through bad experiences that having friends is too much hassle. They always seem to turn on me after a while. Having friends is appealing in principle, but it just doesn’t work out. I am very lonely, but that’s preferable”. |

| Expression of Personal Feelings | A comment in which the writer expresses their personal feelings, emotional response, or opinions/perspectives. | “As someone with autism, I can honestly say I don’t care much about having friends. That wasn’t always the case, as I’ve gotten older, I seem to care less about having friends, but I think that’s normal for a lot of people”. |

| Positive Sentiments | A comment that expresses the writer’s positive beliefs and attitudes towards ASD. | “My 14 year old niece has both. She was diagnosed with ASD last year, but was diagnosed with ADHD when she was much younger... and we’ve always been incredibly close”. |

| Negative Sentiments | A comment that expresses the writer’s negative beliefs and attitudes towards ASD. | “I have Asperger syndrome, but you wouldn’t really notice unless I told you or if you study my behavior closely…and love being social” |

| View on Stereotypes or Misconceptions | Comments that express a writer’s view on stereotypes or misconceptions held by society and perpetuated by the media or other information channels. | “I’m 54 and I have lifetime adhd and asperger’s and it was hell trying to function most of my life as I had never even heard of either one until my late 30’s... as a child back in the 70’s I was diagnosed as hyperactive but that only scratched the surface of my issues”. |

| View on ASD Characteristics | Comments that express a writer’s view on the epidemiology of ASD, associated behaviours, interventions, etc. | “I’ve heard people complaining about schooling and working from home, via internet, while I’m like “Are you kidding? This is heaven!” |

| Reaction to Video Content | Comments expressing a writer’s immediate reaction and feelings toward the information in a video or the way the creator presents it. | “As an autistic person I want to say this for all others out there. We are built different, not incorrectly”. |

| Agreeing with or Approving of Creator Content | A comment that expresses agreement, satisfaction, or gratitude towards the video content. | “Our son just got diagnosed this week which has been such an amazing moment for our family. Really thankful for your content. Had a bit of a cry listening to your Podcast afterwards. Tears of relief and hope. Cheers?” |

| Disagreeing with or Disapproving of Creator Content | A comment that expresses disagreement or condemnation of video content. | “I have a autistic little brother and he’s 7 he can’t speak but tries to communicate he also has repetitive behaviour but Ty for saying this vid means a lot”. |

| Miscellaneous Exclamations | Comments with weak or no correlation to ASD-related content. This category also includes summarizing or directly quoting something in the video, making video requests, and random off-topic jokes, statements, or questions. | “This guy created Task manager, what a legend. All love from programmers around the world! thanks dave”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakombo, S.; Ewalefo, P.; Konkle, A.T.M. The Influence of Social Media on the Perception of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Content Analysis of Public Discourse on YouTube Videos. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043246

Bakombo S, Ewalefo P, Konkle ATM. The Influence of Social Media on the Perception of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Content Analysis of Public Discourse on YouTube Videos. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043246

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakombo, Schwab, Paulette Ewalefo, and Anne T. M. Konkle. 2023. "The Influence of Social Media on the Perception of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Content Analysis of Public Discourse on YouTube Videos" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043246

APA StyleBakombo, S., Ewalefo, P., & Konkle, A. T. M. (2023). The Influence of Social Media on the Perception of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Content Analysis of Public Discourse on YouTube Videos. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043246