Diving into the Resolution Process: Parent’s Reactions to Child’s Diagnosis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

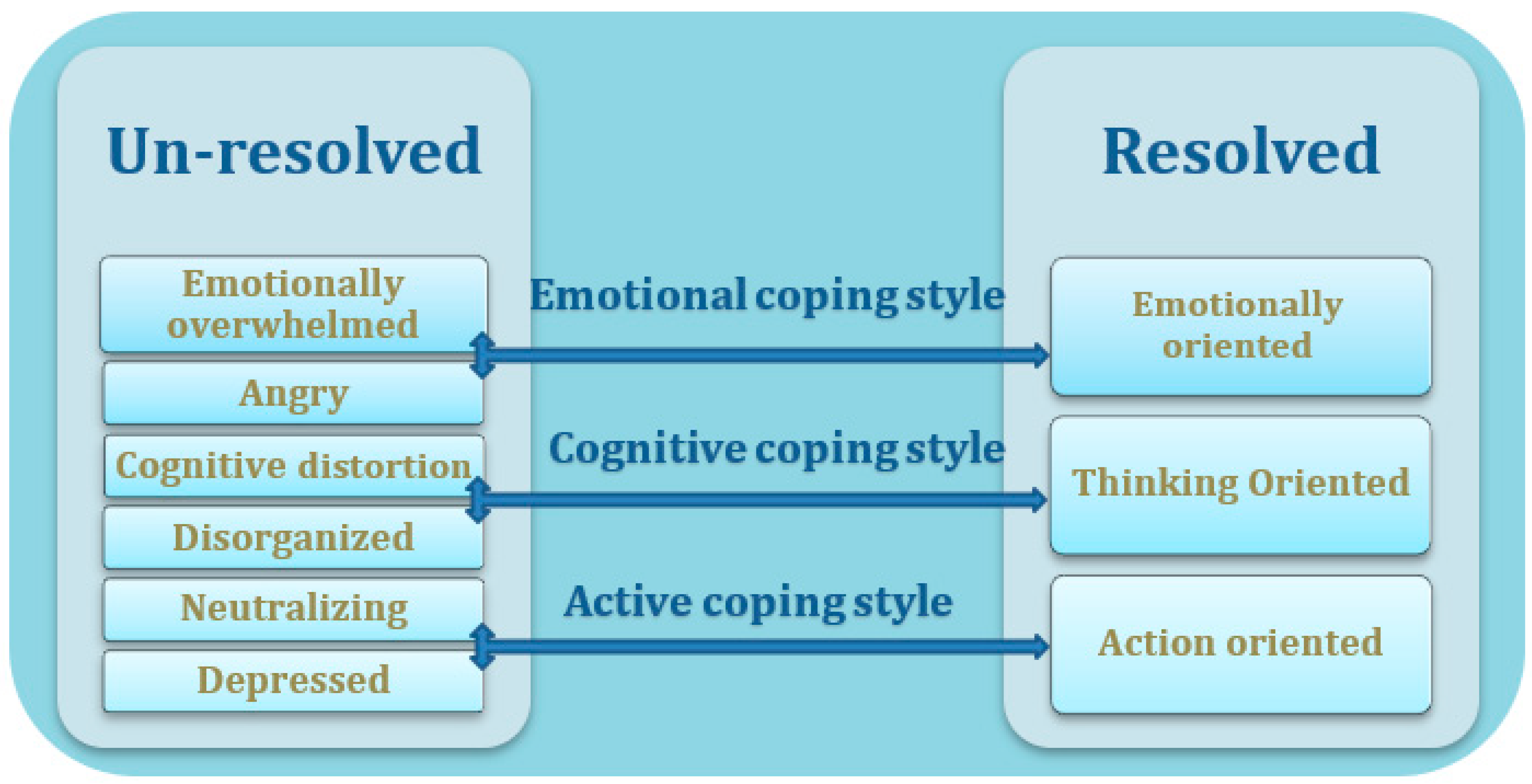

- What was the prevalence of resolution with the diagnosis among parents of children diagnosed with special needs during the last two years?

- What was the distribution of the parental coping styles in regard to the continuum?

- What contents characterize the different coping styles of parents of children with special needs?

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Sampling Method

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Categorical Measure

2.2.2. Qualitative Measure

- Please describe the moment you were informed of your child’s diagnosis.

- Describe your parenting considering the diagnosis.

- Describe how do you cope on a daily basis.

- Describe your emotions while coping with day-to-day situations.

- Describe how do you perceive your parental role towards your child with special needs?

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Research Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Categorical Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.3. Emotions

“From the moment we received the diagnosis, I felt that my world was in ruins and that I was trapped in a profoundly intense storm of emotions. I felt a combination of many unbearable things to the point of collapse. I felt as if I was on a tempestuous sea, being beaten by the waves.”

3.3.1. Guilt

“Sometimes I look at his facial features and I see myself when I was young. Especially when comparing pictures, putting one next to the other. My stomach turns over and I feel that I am responsible; those are my genes.”

3.3.2. Emotional Breakdown

3.3.3. Shame

“I was ashamed in the beginning about what the neighbors or our friends would say about the fact that I had a child like that. It took me time to take him out to parks and playgrounds because it’s really hard. He used to sprawl out on the ground in the middle of the park.”

“Of course, I had concerns about what they would say about my daughter being placed in special education. How would the surroundings react? I was afraid it would be embarrassing…My husband, of course, found it more difficult than I did.”

3.4. Thoughts

3.4.1. Preoccupation with Surrounding Stigma

3.4.2. Troubled about the Child’s Future

3.5. Actions

3.5.1. Concealment

“We saw our friends and family less. We avoided leaving home with him. We didn’t speak freely with our close surroundings. We were always busy hiding, in the family, that perhaps we would succeed in narrowing the gap as time passed.”

3.5.2. Search for Help and Support

“I was surprised at how much the family could help and give support. Even now that my Hodaya is six years old, they still support and help. They actually read about all kinds of treatments and call to tell me. In general, I can say that without my family, managing would be much more difficult. Thank God that we have one another.”

3.5.3. Effort to Reject the Diagnosis

“I was in shock. I felt as though my world was being destroyed… I didn’t understand what it meant… What is autism…I was in denial; I said that it couldn’t be happening to me…Maybe it was a mistake. Maybe if I make an effort and go for another opinion with another doctor, they will tell me it was a mistake…”

4. Discussion

Research Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bujnowska, A.M.; Rodríguez, C.; García, T.; Areces, D.; Marsh, N.V. Coping with stress in parents of children with developmental disabilities. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, M.; Guerriero, V.; Zavattini, G.C.; Petrillo, M.; Racinaro, L.; Bianchi di Castelbianco, F. Parental attunement, insightfulness, and acceptance of child diagnosis in parents of children with autism: Clinical implications. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poslawsky, I.E.; Naber, F.B.; Van Daalen, E.; Van Engeland, H. Parental reaction to early diagnosis of their children’s autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory study. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2014, 45, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.; Giles, A.; White, S.; Osborne, L.A. Actual and perceived speedy diagnoses are associated with mothers’ unresolved reactions to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder for a child. Autism 2019, 23, 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsack-Topolewski, C.N.; Graves, J.M. “I worry about his future!” Challenges to future planning for adult children with ASD. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2020, 23, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak-Levy, Y.; Atzaba-Poria, N. The effects of familial risk and parental resolution on parenting a child with mild intellectual disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, T.; Mihić, I.; Branković, J. “Our story”: Exposition of a group support program for parents of children with developmental disabilities. Child Care Pract. 2021, 27, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, T.; Mihić, L.; Oros, M. Coping strategies and resolution in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. J. Loss Trauma 2017, 22, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milshtein, S.; Yirmiya, N.; Oppenheim, D.; Koren-Karie, N.; Levi, S. Resolution of the diagnosis among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child and parent characteristics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak-Levy, Y.; Atzaba-Poria, N. A mediation model of parental stress, parenting, and risk factors in families having children with mild intellectual disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 98, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, T.; Mihić, L.; Mihić, I. Stress and resolution in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K.A.; Neece, C.L.; McIntyre, L.L.; Blacher, J.; Baker, B.L. Intellectual disability and developmental risk: Promoting intervention to improve child and family well-being. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E.; Dolev, S.; Said, M. Coherence of representations regarding the child, resolution of the child’s diagnosis and emotional availability: A study of Arab-Israeli mothers of children with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3139–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; Marvin, R.S. Manual for Classification of the Reaction to Diagnosis Interview; University of Virginia: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1992; unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, B.; Ungerer, J.; Wastell, C. Implications of resolving the diagnosis of PKU for parents and children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008, 33, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E.; Shahar-Lahav, R. Parents’ resolution of their child’s diagnosis: A scoping review. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2022, 24, 580–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G.W.; Miniscalco, C.; Gillberg, C. Preschoolers assessed for autism: Parent and teacher experiences of the diagnostic process. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 3392–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.; Osborne, L.A. Reaction to diagnosis and subsequent health in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2019, 23, 1442–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feniger-Schaal, R.; Oppenheim, D. Resolution of the diagnosis and maternal sensitivity among mothers of children with intellectual disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak-Levy, Y.; Atzaba-Poria, N. Paternal versus maternal coping styles with child diagnosis of Developmental Delay (DD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 2040–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, Y.R.; McCubbin, M. Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s congenital heart disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 39, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, R.S.; Pianta, R.C. Mothers’ reactions to their child’s diagnosis: Relations with security of attachment. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1996, 25, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasscoe, C.; Smith, J.A. Unraveling complexities involved in parenting a child with cystic fibrosis: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, R.; Gattinara, P.C.; Cioccetti, G.; Ioverno, S. Parents’ reactions to the diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Associations between resolution, family functioning, and child behavior problems. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 25, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, K.; Fung, F.; Hu, A.; Sweller, N.; Wang, W. Understanding Hong Kong Chinese families’ experiences of an autism/ASD diagnosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1164–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, M.D.; Hannon, L.V. Fathers’ orientation to their children’s autism diagnosis: A grounded theory study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, C.A. Father involvement in the care, play, and education of children with autism. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 42, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizbard-Bartov, E.; Yehonatan-Schori, M.; Golan, O. Personal growth experiences of parents to children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawadi, S.; Shrestha, S.; Giri, R.A. Mixed-methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. J. Pract. Stud. Educ. 2021, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.A.; Baranek, G.T.; Sideris, J.; Poe, M.D.; Watson, L.R.; Patten, E.; Miller, H. Sensory Features and Repetitive Behaviours in Children with Autism and Developmental Delays. Autism Res. 2010, 3, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders., 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gentil-Gutiérrez, A.; Cuesta-Gómez, J.L.; Rodríguez-Fernández, P.; González-Bernal, J.J. Implication of the sensory environment in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Perspectives from school. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentil-Gutiérrez, A.; Santamaría-Peláez, M.; Mínguez-Mínguez, L.A.; González-Santos, J.; Fernández-Solana, J.; González-Bernal, J.J. Executive functions in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Grade 1 and 2, vs. neurotypical development: A school view. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkedi, A. Words that Reach out: Qualitative Research—Theories and Applications; Ramot Publishing: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2003. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shkedi, A. Multiple case Narratives: A Qualitative Approach to Studying Multiple Populations; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shlasky, S.; Alpert, B. Ways of Writing Qualitative Research: From Deconstructing Reality to Its Construction as a Text; Mofet/Macam: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2007. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

| Subcategory | Frequencies | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolved | Emotional orientation | 14 | 22.6 |

| Thinking orientation | 14 | 22.6 | |

| Active orientation | 9 | 14.5 | |

| Total | 37 | 59.7 | |

| Unresolved | Emotionally overwhelmed | 9 | 14.5 |

| Angry | 2 | 3.23 | |

| Depressed/passive | 3 | 4.8 | |

| Neutralizing | 2 | 3.23 | |

| Disorganized/confused | 3 | 4.8 | |

| Cognitive distortion | 6 | 9.7 | |

| Total | 25 | 40.3 |

| Coping Style | Frequencies | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional | 25 | 40.3 |

| Cognitive | 25 | 40.3 |

| Active | 12 | 19.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barak-Levy, Y.; Paryente, B. Diving into the Resolution Process: Parent’s Reactions to Child’s Diagnosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043295

Barak-Levy Y, Paryente B. Diving into the Resolution Process: Parent’s Reactions to Child’s Diagnosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043295

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarak-Levy, Yael, and Bilha Paryente. 2023. "Diving into the Resolution Process: Parent’s Reactions to Child’s Diagnosis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043295

APA StyleBarak-Levy, Y., & Paryente, B. (2023). Diving into the Resolution Process: Parent’s Reactions to Child’s Diagnosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043295