1. Introduction

There has been persistent interest in investigating mood as a construct in sport and exercise domains [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Mood has been defined [

2] as “a set of feelings, ephemeral in nature, varying in intensity and duration, and usually involving more than one emotion” (p. 16). Historically, the most frequently used instrument to assess mood has been the Profile of Mood States (POMS; [

5]), a self-report inventory of six mood dimensions: Tension, depression, anger, vigour, fatigue, and confusion. The POMS was initially used to assess mood in clinical populations and was then extended to college student populations [

5]. It has subsequently been shown to be valid for use with athletes in sport and exercise settings and has been used in many sport-related studies [

6].

The original 65-item POMS requires a relatively lengthy completion time of 8–10 min, which has resulted in numerous truncated versions being developed [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Terry and Lane developed and validated a 24-item short version, designed primarily for use in sport and exercise domains, now known as the Brunel Mood Scale (BRUMS) [

11,

12]. The 24-item, 6-factor BRUMS has undergone rigorous validity testing and has demonstrated satisfactory predictive, concurrent, criterion, and factorial validity, and appropriate test–retest reliability [

11,

12].

Mood profiling is a process in which mood scale scores are plotted against normative scores to provide a graphical representation of mood states [

3]. Its application in sports gained popularity following studies by Morgan [

3,

13], who showed that an iceberg profile (characterised by an above-average vigour score and below-average scores for tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion) was predictive of successful performance. Subsequent studies have identified other distinct mood profiles among athletes, such as the Everest profile [

4] (characterised by near-maximum scores for vigour and near-zero scores for tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion), which—like the iceberg profile—has been linked with successful performance. Conversely, the inverse iceberg profile (characterised by a below-average vigour score and above-average scores for tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion), has been associated with suboptimal performance and a heightened risk of psychopathology [

14].

The BRUMS and the associated norms were developed on and for use by English-speaking respondents, which creates challenges for sport psychology practitioners who work in other language contexts. To ensure the effective application of mood profiling across cultures and countries, it is essential to translate the BRUMS to capture cultural and linguistic nuances. To do this, comprehensive translation and validation processes are required to extend the cross-cultural generalizability of the BRUMS. This has most recently been applied to a validation of the Lithuanian-language version of the Brunel Mood Scale (BRUMS-LTU) [

15], with the BRUMS previously being translated and cross-validated in Afrikaans [

16], Bangla [

17], Brazilian Portuguese [

18], Chinese [

19], Czech [

20], French [

21], Hungarian [

22], Italian [

22,

23], Japanese [

24], Persian [

25], Serbian [

26], Spanish [

27], and Turkish [

28] contexts.

In a Malaysian context, two previous studies have tested Malay translations of the BRUMS [

29,

30], although both have limitations. For example, the Hashim et al. study [

29] failed to provide details of the translation procedure, and the sample consisted of only adolescent athletes from one geographical location, the majority of whom competed in the sport of taekwondo. This raises questions about the generalizability of study results to other age groups (e.g., older athletes in Malaysia), other regions of the country, and athletes from other sports (e.g., field hockey, soccer). The Lane et al. study [

30] was methodologically stronger having implemented a rigorous method to generate Malay mood descriptors. Additionally, the sample was larger and more diverse in comparison to the Hashim et al. study. The respondents were athletes taken from across Malaysia who together participated in more than 30 different sports. However, the sample included a high proportion of adolescent athletes, again raising questions about the generalizability of results to other age groups. Additionally, ethnicity was not considered in either study. As Malaysia is an ethnically diverse country, it is not clear if findings are representative of this diversity. Given these concerns, the utility and efficacy of the existing Malay translations of the BRUMS remains questionable. As highlighted by McGannon et al. [

31], and Ryba et al. [

32], cultural awareness and cultural competence are acknowledged as key elements of effective practice and delivery of sport psychology to address the requirements of participants from culturally diverse nations. The multicultural diversification underlying the Malaysian nation, and more specifically in the elite sports setting, provides a strong imperative to conduct further cross-cultural research in the Malaysian context.

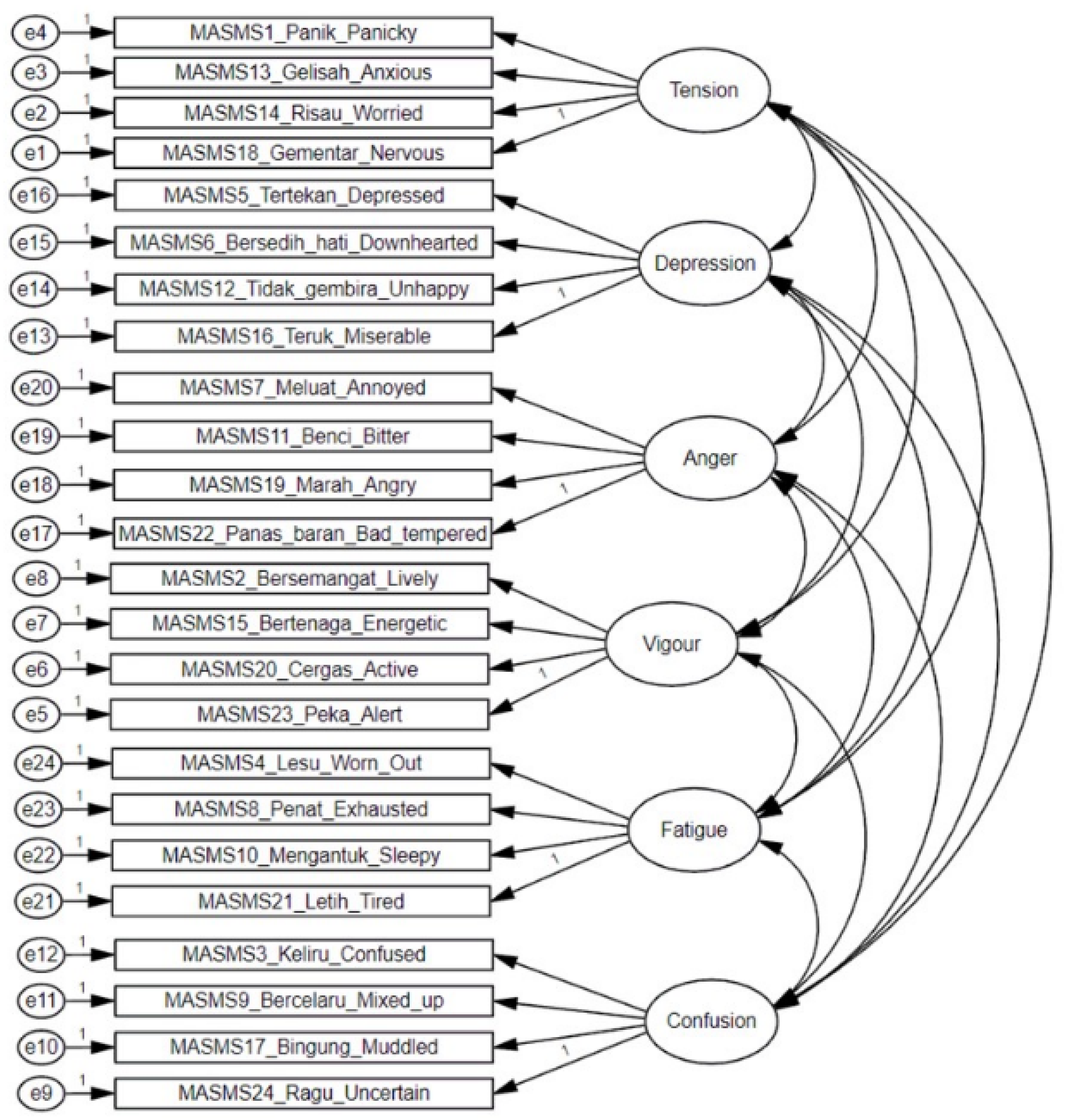

Therefore, the primary purpose of our study was to validate a Malay translation of the BRUMS, referred to as the Malaysian Mood Scale (MASMS; See

Appendix A). The psychometric properties of the MASMS were evaluated against the original measurement model of the BRUMS [

11,

12]. It was hypothesised that the MASMS subscale scores would highly correlate with concurrent measures of similar constructs (i.e., convergent validity) and show minimal correlation with concurrent measures of dissimilar constructs (i.e., divergent validity) [

33]. It was also hypothesised that negatively valanced MASMS scales would correlate with concurrent measures of depression, anxiety, and stress [

23]. The secondary purpose of our study, based on previous evidence of the influence of demographic variables on mood responses [

34,

35], was to test for differences in mood scores between athletes and non-athletes, males and females, and younger and older participants.

4. Discussion

Our primary purpose was to validate a Malay language version of the BRUMS. The factorial validity, internal consistency, concurrent validity, and test–retest validity of the MASMS were evaluated in a Malay-speaking sample, which consisted of athlete and non-athlete participants. The six-factor measurement model was supported, with fit indices providing evidence of adequate model fit (see

Table 2). Multisample CFA analyses supported factorial invariance across subsamples grouped by sport participation, sex, and age group.

Factor intercorrelations were in line with theoretical predictions (see

Table 3). The negative orientation subscales of tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion were all significantly intercorrelated and inversely correlated with vigour scores. The convergent and divergent validity of the MASMS was supported via relationships with depression, anxiety, and stress as measured by the Malay version of the DASS-21. Negatively-valenced MASMS scales correlated with DASS-21 subscales, demonstrating convergent validity, and the MASMS vigour scale correlated negatively with DASS-21 subscales, demonstrating divergent validity. The test–retest reliability of the MASMS was also supported.

Development of the MASMS reinforces the importance of conducting research with culturally appropriate measures [

31,

32] and offers a range of applications for researchers and applied practitioners who work in a Malaysian context. From a research perspective, the MASMS provides a measure of mood with comprehensible terminology and adequate attention to cultural nuances, thereby creating an impetus for mood-related research with standardised measures within the ethnic and cultural diversity of the Malaysian setting. The validated MASMS provides increased opportunity to conduct multicultural research in Malaysia, notably testing and possibly updating Lane and Terry’s conceptual model of mood–performance relationships [

2], Morgan’s mental health model [

56], and replicating research on the predictive effectiveness of mood assessments on performance in sports such as aikido [

57], field hockey [

58], karate [

59], swimming [

60], and triathlon [

61]. The MASMS could also be used to investigate the prevalence of the previously identified six mood profile clusters, namely, the iceberg, inverse iceberg, inverse Everest, surface, submerged, and shark-fin profiles [

35,

48,

62], among the Malaysian population. Another future research direction would be to investigate how the six mood profiles [

35,

48,

62] affect performance among Malaysian athletes. The brevity of the MASMS promotes mood assessment in research environments with limited time availability for data collection, specifically prior to competition or during intervals of sporting events, and helps to support the initiation of relevant individualised mood management strategies.

There has been increased attention on mental health and well-being in a sporting context, especially for athletes competing at the elite level [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. For example, a qualitative study looking at the mental health of Malaysian elite athletes [

69] argued that experiencing stressful physical and psychological demands during training and competition placed athletes at risk of developing adverse moods that negatively affected their mental health and psychological status. Further, a call to develop a more comprehensive framework to foster athletes’ mental health and well-being [

70] suggests a need to better identify and intervene early to prevent mental health issues. Therefore, with the potential of implementing mood profiling as an indicator of psychopathology risk [

71], the MASMS could be an effective mental health screening assessment to identify and monitor mood states of athletes in Malaysian sports. This may go some way towards achieving sustainable athlete psychological well-being. In clinical domains, future studies may include the MASMS to assess prevalence of mental health issues [

71,

72], as a measure for medical screening protocols [

73], and to monitor cardiopulmonary and metabolic rehabilitation patients [

74] in the Malaysian healthcare system.

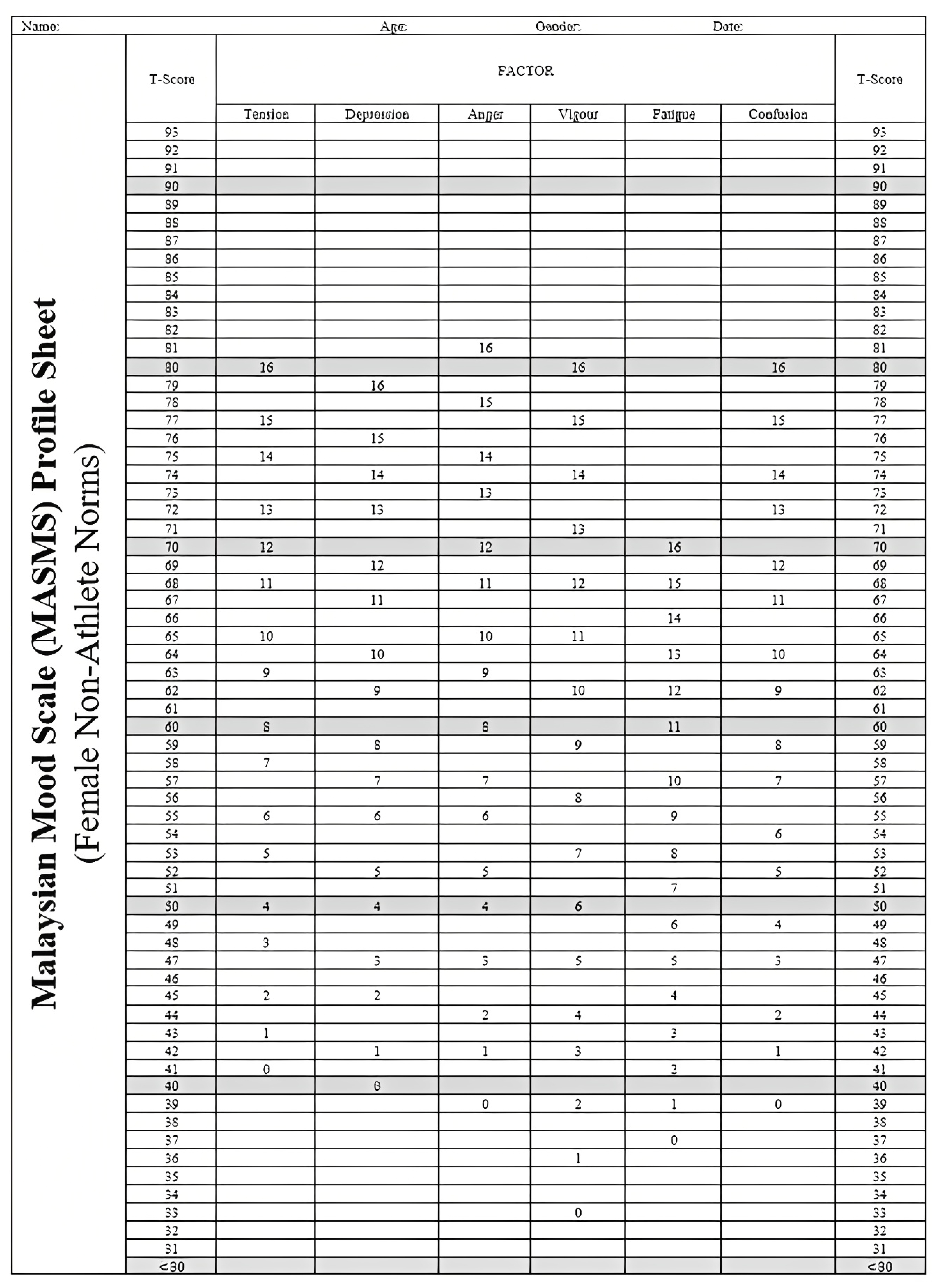

For the applied practitioner, multifaceted applications of mood profiling in the sport domain (refer [

4] for a review) may also benefit sporting athletes and teams in Malaysia. Terry [

4] suggested that regular mood profiling can function as an effective mechanism for sport psychology practitioners in monitoring athlete mindset. It can serve as a catalyst for discussion in one-to-one sessions, as a systematic way to monitor optimal training load, assess reactions to acclimatisation, as an indicator of general wellness, during the injury rehabilitation process, and for performance prediction among elite performers. Further, the importance of understanding idiosyncratic relationships between mood and performance has also been emphasised [

4]. Replicating the approach used with the BRUMS [

75], a user-friendly manual of the MASMS should be generated to provide a reference for practitioners and researchers for the application of the MASMS in Malaysia. The tables of normative data (see

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8) generated as a part of the present study will assist in the interpretation of MASMS raw scores. To generate graphical representation and interpretation of individual mood profiles, the standardised scores can be plotted on the relevant profile sheet (see

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4 and

Figure A5 in

Appendix C). There is scope to introduce evidence-based mood-regulation techniques where appropriate.

With increased emphasis placed on the importance of monitoring athlete mental health status and personal well-being [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69], the MASMS could be used as an efficient self-report measure of mood for monitoring training load responses to reduce risk of overtraining and burnout [

76,

77], especially given the rigorous demands of training and competition. Further, a recent meta-analysis by Trabelsi et al. [

78] reported significant mood deterioration, specifically in the form of increased fatigue and decreased vigour, among athletes who continued to train and compete whilst also observing the food and fluid restrictions of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. Given that many of Malaysia’s elite athletes are Muslims who similarly observe these restrictions, there may be benefits associated with increased monitoring of their mood during the annual Ramadan period.

Regarding our secondary purpose, significant differences in mood responses were identified for sport participation, sex, and age. Athletes in our sample reported more positive moods than non-athletes, with significant differences on all six subscales, which is consistent with previous findings [

23,

49]. Positive mood can be promoted through engagement in aerobic exercise [

79] and long-term physical activity [

80], both of which would be typical behaviours for athletes. Overall, being physically active has well-established mood-enhancing effects [

81,

82,

83,

84,

85], thereby alleviating manifestations of negative mood [

86].

Variation in mood scores between males and females was also identified in our study. This is consistent with Iranian [

25], Italian [

23], South African [

16], Serbian [

26], Singaporean [

87], and Spanish [

27] studies, wherein females reported more negative moods than males, with lower scores for vigour, and higher scores for tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion. This result is consistent with the findings of the Malaysian National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019 [

88], wherein females reported a higher prevalence of mental health issues than males. On a global scale, it has been reported that females are nearly twice as likely to experience mental disorders as males [

89], although this may be at least partially explained by the greater willingness of females to seek professional assistance for mental health issues [

90]. Among the explanations for sex differences in mood responses is the potential of mood disturbance linked to endocrine changes associated with females’ reproductive life cycle (e.g., menstruation, pregnancy, menopause) [

91,

92] and the experience of mood disorders due to societal challenges (e.g., workforce inequality, sex discrimination) [

93] that are more prevalent among females. It has also been identified that males are less likely than females to engage in rumination [

94] and are less likely to report negative feelings (e.g., nervous, overwhelmed, depressed) [

95] than females, although there is evidence that males tend to conceal symptoms of mental ill health which may lead to under-reporting and under-diagnosis of negative moods [

96].

In relation to age, our results are inconsistent with some previous studies. Older participants in the current study reported higher scores than younger participants for tension and confusion and lower scores for vigour and fatigue, whereas the reverse has been found in English-speaking and Singaporean samples [

34,

49]. However, our results are consistent with Malaysian age-group findings in the NHMS report [

88], in which older adults (30–74 years old) had a higher prevalence (15.3%) of mental health issues than younger adults (15–29 years old; 9.1%). Elderly Malaysians tend to have less formal education and lower fitness levels than their younger counterparts [

88], characteristics that may increase mental health risk. In our sample, participants aged 50–75 years had the highest level of “no formal education” or “primary education only,” and generally did not participate in sporting activities. Unfortunately, health literacy in Malaysia is curtailed for older and less educated groups [

88]; thus, older citizens may be oblivious to the knowledge that involvement in sport and exercise can help protect against mental ill-health [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86]. Use of the MASMS as a mental health screening tool among all Malaysians, but particularly those in the older age groups, may prove beneficial in identifying “at risk” individuals at an early stage, which is noted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an important intervention in promoting healthy ageing [

97].

Some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. Firstly, despite gathering one of the largest samples among BRUMS translation studies, all data were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The lived experience of COVID pandemic restrictions has caused widespread mood deterioration [

98], which may restrict the relevance of the tables of normative data to the Malaysian population at the current time. It is recommended that further research using the MASMS be conducted to assess whether refinement of norms is required. This would also enable researchers to track the impact of COVID on mental health in Malaysia. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet over, it would also be fruitful to conduct studies to explore the impact of pandemic challenges (e.g., physical distancing, lockdown, economic fallout, travel restriction) on mood disturbance, which may be beneficial in identifying effective coping strategies to reduce any negative impact the pandemic may have on mental well-being. A second limitation relates to the age of the participants, as no mood-profiling data were obtained from individuals under 17 years of age. According to the demographic statistics reported by DOSM [

36], approximately 23% of the total population of Malaysia is <15 years old. Therefore, assessing the mood of the participants in that age group, as done in previous studies [

11,

19], would enhance the generalisability of the MASMS to a wider age range.

Finally, additional investigation of the antecedents, correlates, and behavioural consequences of mood responses among athletes and non-athletes in Malaysia is suggested. The interaction between socio-demographic factors and health status (e.g., availability of social support services, place of residence, level of household income, marital status, dietary habits, physical condition, amount of physical activity conducted) may provide further insights into the mood profiles among the Malaysian population across the age distributions. Extending the investigation of the MASMS among targeted groups of participants beyond the world of sport and exercise (e.g., youth, seniors) across various contexts, including academia, health professions, and the military, would be informative in expanding the range of mood-profiling applications in a Malaysian context.