1. Introduction

Violence against women (VAW) is highly prevalent globally, and evidence indicates both its pervasive nature and its serious and long-term impacts on women’s health [

1]. Research has shown that healthcare providers (HCPs) are often the first point of contact for women facing violence and that women are willing to disclose their experience of violence to the HCP if they feel safe and that they will be believed [

2,

3]. HCPs can play a central role in the health system response for mitigating VAW by the identification of abuse as a part of routine clinical practice. In addition to the provision of care, the role of the health system has also been recognized in the prevention of violence, including by documenting cases and generating evidence on the health burden of VAW [

4].

One of the critical factors that contribute to a strong health system response to VAW is HCPs’ willingness and ability to identify and support women affected by violence. However, there is substantial evidence suggesting that there are several institutional and socio-cultural barriers that prevent HCPs from responding to violence against women [

5]. Some of these factors include a lack of training of HCPs, an absence of standard operating procedures/protocols, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of referral linkages with other services needed by the survivors. While the role of the health system is critical in responding to VAW, it is a social institution which can be characterized by inequitable norms, gender power relations, patriarchy, and class- and caste-based discrimination [

6]. There is well-documented evidence that HCPs may have negative attitudes towards women disclosing violence in a healthcare setting, including blaming women for the violence that they experience [

7,

8]. A recent qualitative meta-synthesis identified frustration at women not taking HCPs’ advice as a personal barrier for HCPs addressing IPV [

9]. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that positive relationships with HCPs can facilitate [

10] and that, where HCPs are given adequate training and structural support, they feel equipped and empowered to support women [

11].

In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the Clinical and Policy Guidelines (the Guidelines) to provide evidence-based recommendations for clinical care and health systems strengthening that included guidance on training HCPs and improving the service readiness to respond to intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence against women [

12]. To date, however, evidence on how to implement the training and service readiness recommendations into the health system response in low- and middle-income contexts (LMICs) has been limited.

Building the capacity of HCPs to identify and provide first-line support is considered essential to providing survivor-centered care to women subjected to violence. A systematic review of the integration of the health service response to IPV in LMICs found that the training of HCPs was a key element in a comprehensive integrated health sector response [

8]. HCPs should not only identify women who are affected by violence but also provide an empathetic response to survivors and, where necessary, make appropriate referrals [

13]. A recent systematic review of evaluations of training programs for improving HCPs’ response to VAW indicates significant gaps in evidence concerning the effectiveness of training interventions, with only 19 trials of evaluations of IPV training programs or educational interventions identified, three-quarters of which were conducted in the United States [

14]. A study in Sri Lanka found roleplays, field handbooks, and the cultural sensitivity of the training content to be important for building the capacity of midwives in responding to violence [

15]. An improved understanding of the perspective and experience of HCPs themselves, particularly in LMIC settings, in undergoing these trainings could support improvements and the scale-up of appropriate capacity-building approaches. The training of HCPs needs to address awareness, build skills, and address prejudicial attitudes towards and stereotypes of VAW. Moreover, training interventions need to be part of a broader set of systems strengthening activities that address the barriers and enablers in the provision of quality care to survivors.

In India, the recent National Family Health Survey (2019–20) has shown that 29% of women aged 18 to 49 years have experienced physical or sexual violence from their spouses (i.e., domestic violence or intimate partner violence) in India, while for the state of Maharashtra, it was found to be 25% [

16]. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA), which came into force in 2005, placed a specific responsibility on health professionals to treat and respond to women and children facing domestic violence and also declared medical institutions as service providers [

17]. The National Health Policy (2017) also, for the first time, identified the role of the health system in addressing VAW [

18].

Despite a supportive policy environment, evidence on how best to integrate a VAW response within the health system is limited within India. The Indian government has extensively supported the model of the One-Stop Crisis Centers (OSCC) to address VAW, but there are several concerns about accessibility, effectiveness, and a lack of integration into existing health systems [

19]. There are several small-scale or pilot health facility-based interventions, mostly by non-government organizations (NGOs), but there are no evaluations of these interventions. The documentation of OSCC and pilot health facility interventions reinforces the case for integrating the VAW response into health facilities, as a large number of women access hospital-based services [

20]. The documentation highlights that the successful institutionalization of VAW responses requires a core group of trainers to be in place in health facilities in order to establish the ongoing training of HCPs.

In 2019, the Center for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT), a Mumbai-based research organization, collaborated with the Special Program of Research on Human Reproduction (HRP) housed at the World Health Organization (WHO), with the aim of strengthening evidence in LMIC contexts. The study focused on how best to improve the health system response to VAW by implementing the WHO Guidelines for responding to domestic violence and sexual violence against women in Maharashtra, India, through a multi-component implementation research study. The overall study design was a mixed-methods study that utilized a pre-and post-intervention design with no comparison group. It was intentionally designed as a formative phase to determine the acceptability of the interventions and identify relevant adaptations. The intervention comprised not only the training of HCPs but also health service delivery/systems strengthening components, as per the recommendations in the WHO Guidelines (see Methods, sub-section intervention activities). The study protocol for the research and a description of the intervention are published elsewhere [

21].

Two specific sub-objectives of the study were (1) to assess changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices as a result of the intervention and (2) to assess the relevance of the intervention and identify facilitators and barriers faced by HCPs in delivering quality care to women subjected to violence. The results of the first sub-objective were obtained through a pre-, post-training, and post-6 months intervention survey and are published elsewhere [

22].

For the second sub-objective, and specifically relevant to the findings presented in this paper, we used qualitative methods (i) to assess the relevance of the training approaches in meeting the needs of HCPs; and (ii) to identify barriers and facilitators regarding delivering healthcare to women subjected to violence.

2. Materials and Methods

The study involved quantitative pre- and post-intervention design. Qualitative data were collected after the training and intervention activities were completed. A phenomenological approach was taken to the qualitative data with in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) to capture the perspectives and perceptions of trained HCPs regarding their experience of intervention. The data collection had a particular focus on what they learned from the training, how they were able to apply the training, and what contextual factors, including barriers or enablers within their institutional context, influenced their ability to apply their training to deliver care. The study employs this approach, as the phenomenological perspective is able to capture “the experience of being in the world, arising from the interaction between individuals and their surroundings,” which is a key aspect of improving the understanding of HCPs’ experiences of training [

23]. This approach helps in capturing individual perceptions and gaining insights into the motivations and actions of the individual, setting aside any assumptions or hypotheses about the phenomenon. HCPs’ experiences are approached in light of the framework of the health systems approach to VAW, which positions HCPs supporting clients as the basis of a women-centered response, requiring key elements of the health system—including leadership and governance, coordination, and service delivery—to be in place to enable HCPs to implement a quality VAW response.

2.1. Setting

The study was conducted in three tertiary hospitals located in two districts of Maharashtra State in the western part of India. The hospitals were the Aurangabad Government Medical College, the Miraj Medical College, and the Sangli District Hospital. We assumed that, for training intervention to be feasible and effective at the level of primary health centers, we first needed to assess feasibility and effectiveness in a relatively well-resourced setting, the tertiary level facilities. These facilities were selected, as they had collaborated with CEHAT for a previous project on integrating gender in the medical education curriculum.

The Aurangabad district has a population of about 3.7 million, and the Government Medical College with 1000 beds is the biggest hospital, catering to both urban and rural populations. On average, the facility serves about 27,000 patients per month on outpatient visits and about 5600 per month on in-patient visits. Miraj medical college, with 320 beds, caters to patients in the Sangli district, which has a population of 2.8 million. The Miraj Medical College also manages the Sangli District Hospital, which has 380 beds. HCPs rotate and are shared between the Miraj Medical College and the Sangli District Hospital. About 52,000 patients visit Miraj Medical College and Sangli District Hospital every month for out-patient services. This project was implemented in three departments—Obstetrics & Gynecology, Medicine, and Casualty. It was decided that the trainers and providers from these three departments would be trained, as female patients are more likely to seek healthcare services from these departments.

2.2. Intervention

Training was implemented using a cascade approach involving the training of master trainers, followed by the training of HCPs. A pool of 26 master trainers, comprising doctors, nurses, and social workers, was created. These master trainers were selected based on their seniority and administrative or managerial responsibilities and on whether they were likely to be posted in the same health facility during the duration of the study. The master trainers were trained through 5-day training. The training used the WHO curriculum, Caring for Women Subjected to Violence (based on the WHO Guidelines), adapted to the Indian context by CEHAT [

24].

The training focused on increasing the knowledge of providers about violence against women as a public health issue, signs and symptoms indicating violence, and the legal mandate of providers to respond to violence. The training built HCPs’ skills regarding how to ask women about violence based on signs and symptoms, provide first-line support, refer women to other support services, and document cases. One of the key skills in the training was the provision of first-line support through a job aid called “LIVES”, which involves five steps: Listen with empathy, Inquire about needs and concerns, Validate, Enhance safety, and facilitate social Support [

12]. The content of the training took into account the fact that changes in HCPs’ behaviors also require them to critically reflect on their own gender-related attitudes and beliefs [

25]. Therefore, training activities included discussions on gender discrimination, patriarchy, and intersectionality to build an understanding of the underlying causes of violence against women. Values clarification exercises emphasized respecting women’s autonomy and communicating in a non-judgemental and empathetic manner.

2.3. Research Participants and Sampling

For the qualitative data collection, out of a total of 220 HCPs (a total of 220 providers of different cadres were trained by master trainers across three hospitals in eight batches of approximately 30 HCPs) who were trained, 21 were selected for in-depth interviews (IDIs). In-depth interviews (IDI) were conducted approximately 6 months after the HCPs were trained. Additionally, two FGDs were also carried out with a group of five nurses each. Three IDI participants for whom interviews had been scheduled did not arrive on the day of the scheduled interview. No participants who arrived for the interview refused to participate.

The use of FGDs allowed researchers to collect data emerging from the interactions between the participants and the divergence and convergence of participants’ perceptions [

26].

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the profile of providers who interviewed and participated in focus group discussions. The focus group discussion at each health facility included five nurses from three departments. The participants of the FGDs had a common profile; all were staff nurses with similar years of experience. The participants interviewed for the IDI were selected purposively to represent the different cadres (i.e., doctors and nurses) across the three departments from each of the three hospitals and to cover different levels of experience. Additionally, they were selected based on their availability within the health facility when the data were collected. The sample size was based on feasibility and the accessibility of respondents, rather than data saturation, which was not assessed explicitly throughout the study. While the explicit assessment of data saturation may be necessary in grounded theory studies seeking to develop new theory, it is not always a useful guide for determining the sample size [

27]. A recent systematic review of empirical tests for data saturation suggests that, for a relatively homogenous population, as is the case in the current study, the sample size utilized is adequate for achieving data saturation [

28]. Additionally, we balanced considerations of data saturation with the feasibility of conducting the interviews with HCPs who are busy and, as such, have little time outside their clinical duties.

2.4. Data Collection

Interview guides were developed for IDIs and FGDs. The questions allowed researchers to explore themes systematically and comprehensively while keeping the interviews focused due to the limited time that providers have for participation in interviews. The interview guide was semi-structured, covering the key domains of the study, and the questions were listed with potential probes.

Face-to-face IDIs and FGDs were carried out on the premises of the hospitals. A private space was identified in order to conduct the interviews at times that were convenient for the participant. For every IDI and FGD, two researchers were present. The interviews were conducted by three female senior researchers who are not authors of this manuscript but are credited in the acknowledgements. The interviewers did not have prior relationships with the respondents, and prior to the interview, the interviewers introduced themselves to the participants and provided information about the research study, the name of the organization (CEHAT and WHO), the purpose of the study, and what participation in the study entails. A detailed information sheet about the project was given to each respondent, along with an informed consent form in English and Marathi (the local language), as per the ethical guidelines for social science research.

One researcher led the interview, while the other took notes to validate the transcripts of the audio recording. The researchers were trained in qualitative data collection methods and had prior experience with qualitative research methods. Written informed consent was obtained from participants, including for the audio recordings. All participants consented. The interviews were conducted in English and Marathi. Each IDI lasted for an average of about 35 to 40 min, and each respondent was interviewed once. The FGDs lasted for 50 to 60 min. The participants of the IDI and the FGDs participants were informed regarding the confidentiality of the information discussed in the IDIs and FGDs. Additionally, the participants in the FGDs were also reminded of the importance of not divulging any information about individuals that could risk their confidentiality with others in the group.

2.5. Data Analysis

The recorded IDI and FGDs were transferred to a computer, transcribed, and translated into English in Microsoft Word by researchers from CEHAT involved in data collection. A team of researchers not involved in data collection reviewed, transcribed, and translated the interviews for quality assurance. The transcripts were transferred to qualitative analysis software—Atlas.ti (Version 6)—for coding and data analysis. The data were analyzed using a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding by two members of the research team (SA, PBD) [

29]. A draft codebook was developed based on the themes in the interview guide and the research questions and included a definition of the code and instructions on when to use. Both SA and PB coded all the transcripts individually and then worked together to combine and consolidate the codebook. The researchers assigned codes to the data, as per the codebook. Thereafter, different codes were connected and higher-order themes were aggregated. The team of researchers involved in the codebook development and coding have extensive experience with qualitative research, including an academic background in social sciences and public health, and worked at CEHAT or WHO during the study.

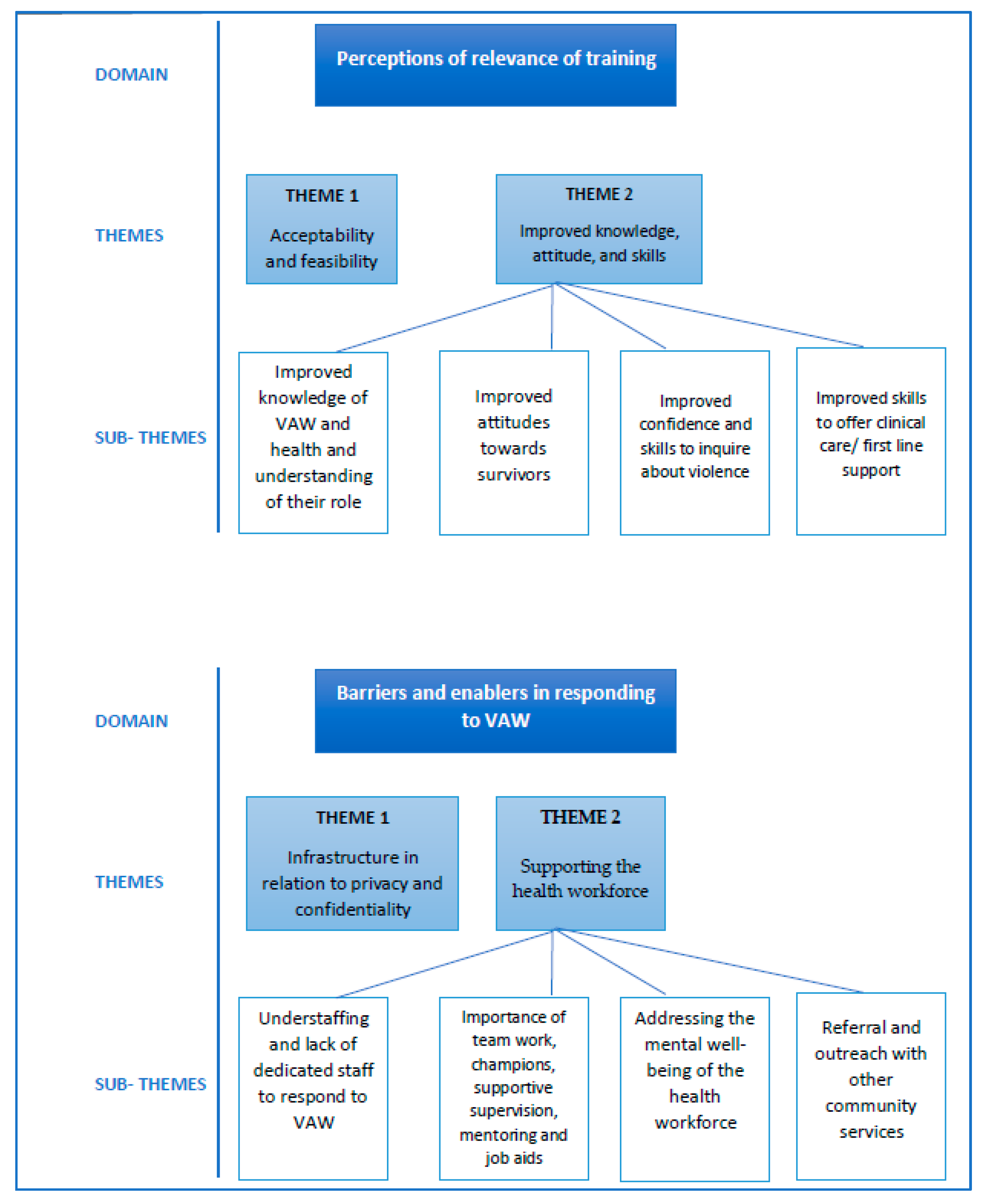

The data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach based on a framework of the health systems approach to responding to VAW [

4], which adapted the WHO health systems building blocks. Specifically, the data explored the following themes under the objective of perceptions of relevance: acceptability and feasibility of the intervention and improved knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Under the objective of identifying barriers and enablers regarding responding to VAW, the themes were infrastructure in relation to privacy and supporting the health workforce (see

Figure 1 for themes and sub-themes).

Ethical Considerations

The implementation of the overall study followed the WHO recommendations in “Ethical and safety recommendations for intervention research on violence against women” [

30]. Appropriate measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality of the information provided by the participants. All interviews were conducted in a private space within the health facility. The data, including audio recordings, transcripts, and databases, were password-protected, and only members of the research team were able to access the data. The identifying information was removed and was linked to an anonymous number which was stored in a separate locked electronic file. All components of this intervention research project were reviewed and approved at different stages by an independent technical review panel of HRP—i.e., Research Project Review Panel (RP2); (ii) the World Health Organization’s Ethics Review Committee (ERC), which reviews all human subjects research conducted or supported by the WHO; and (iii) CEHAT’s Program Development Committee, as well as an independent review committee of research ethics experts that reviews all research protocols of CEHAT.

3. Results

The results section is structured according to the relevance of the research questions. We applied the phenomenological approach, which is commonly used in healthcare research [

31,

32], and chose to organize the experiences of the health providers who participated in the intervention into two overarching domains: Perceptions in relation to the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention; and Barriers and enablers regarding implementing the intervention.

3.1. Relevance of the Training: Acceptability and Feasibility

All respondents had good recall about the content they learned. They were able to list all of the core topics covered in the 2-day training. They mentioned learning about forms of violence, their impact on women’s health, laws related to violence, and services available to women affected by violence, such as protection officers and shelters. They also emphasized that the training had imparted upon them skills regarding how to communicate with patients, how to ask about abuse, when to ask about abuse, why privacy and confidentiality are so important, and how to ensure privacy and confidentiality. Most respondents reported that they had not known about the Domestic Violence Law prior to the training. They were not aware of this civil law and the various provisions under it.

In terms of the design and implementation of the training, the respondents emphasized that the use of participatory methods had enabled them to better understand the issue of violence against women. They spoke about the appropriateness and usefulness of the different approaches employed for the delivery of training. For example, they recognized the value of the training conducted by senior clinicians. HCPs reported that the presence and leadership of senior doctors and nurses were beneficial for integrating responses to VAW, as the senior doctors and nurses (referred to as seniors by the participants) demonstrated what to do by setting an example and could be approached by the new trainees for support. One respondent noted,

As our seniors were there, they told us how we can integrate it into our routine. This our seniors explained to us, how we must follow it in our routines.

[Doctor, Male, 25-year-old, OBGY]

The respondents valued the training and indicated that the method of implementation was feasible and effective for their context. One respondent explained,

Such training should continue. The department should take initiative in deputing staff, deciding who will be the trainers and roles and responsibilities of other staff members. We don’t need money for all this and we can easily provide a space for conducting training. The only thing required is that the initiative should come from seniors.

[Nurse, Female, 35-year-old, Casualty]

The way in which the training was rolled out in the hospitals enabled the staff to ensure that their clinical duties were adequately covered such that participation was practical within the constraints of their working environments. One respondent recalled,

Mostly, such training is pre-planned and we can schedule our duties accordingly. Also, locums (A locum is a temporary appointment of a health care provider to fulfill the duties of another healthcare provider) were arranged for this purpose. So, we didn’t face any problem.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

The HCPs strongly recommended that all cadres at the facility level be trained in responding to VAW. The respondents also emphasized the need for ongoing training, rather than one-time training, and supported further integration of the training throughout their facilities, including pre-service medical education:

It is important to train everyone. If there are providers who are not trained and are not sympathetic towards women, then the efforts that trained doctors are putting are going in vain. There is no point in telling women that we are there to help them. She will not believe us because of her experience with providers who are not trained.

[Doctor, Male, 59-year-old, OBGY]

3.2. Relevance of the Training: Improved Knowledge, Attitudes, and Skills

The HCPs who participated in the training indicated that the training improved their knowledge, that they became more empathetic towards survivors’ situations, and that they learned skills in identifying and responding to VAW.

3.2.1. Improved Knowledge of VAW and Health and Understanding of Their Role

One of the main outcomes of the training, as stated by the respondents, was shifting HCPs’ perceptions of VAW from a strictly legal/police issue to accepting it as a health issue. The training enabled them to better understand their role in supporting women affected by violence. As one respondent explained:

The training made us understand why women reach us with the same health problems again and again. And we as doctors are not be able to identify any possible cause for the health problem because her health problems are related to domestic violence…they are having issues at home.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

The providers reported that the training helped them to recognize how violence was affecting the health of their patients. The HCPs reported that they no longer perceived violence against women solely as a family matter. According to one respondent:

Earlier, I used to hesitate as this is an extremely personal matter. I used to feel that “How can I ask this to woman”? But now, there is no such hesitation because I have understood that violence is directly related to a woman’s health. I used to think that woman must have done something wrong…there is nothing that we can do.

[Nurse, Female, 51-year-old, OBGY]

Another respondent, noting the responsibilities that go with their patients having faith in them, stated,

The thing is that nobody from her family will come to know that she is seeking help from hospital for domestic violence. Also, I feel that majority of patients have a lot of faith in doctors and nurses…especially patients who come from rural areas.

[Doctor, Male, 27-year-old, Medicine]

The training also helped the participants further contextualize women’s reluctance to follow through or uptake particular healthcare advice as a sign that violence may be an underlying factor. As one respondent explained:

We used to tell them [the women] that you must get it [the test] done, and tell them to go. But after the training, we got to know that she may be facing troubles at home because of which she has not carried out any investigations. A different thing we got to know was that she is not responsible for this matter.

[Doctor, Female, 25-year-old, OBGY]

Another doctor explained,

We got sensitized because of the training and whenever we get a case where a woman’s health is neglected then we suspect that there can be violence. Like cases of anaemia are there and if her health is not improving even after taking medication we suspect violence. In such cases we try to ask women about violence. Like this, our approach has changed after training.

[Doctor, Male, 49-year-old, OBGY]

The respondents indicated that the training helped them to understand that experiences of violence may be the cause of or be related to the symptoms with which women were presenting. They recognized that responding to violence against women as part of their clinical care would improve the quality of care and provide a more holistic response to medical issues.

The training helped the participants to recognize different forms of violence. In particular, the respondents indicated that the training enabled them to understand that many contexts of violence involve perpetrators beyond the woman’s partner—for example, other members of the family. In addition, the training broadened the participants’ views of what constitutes violence, beyond physical or sexual violence, to also encompass emotional abuse and economic control. As one doctor explained,

I used to think that only physical violence exists. I was not aware of emotional violence where abuser is not doing anything physically but disturbing woman mentally…. constantly making her feel bad….telling her you are not worth anything.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

Another provider recognized forced sex within marriage as a form of violence:

Sexual violence also happens in marital relationships…husband forces wife for sex. It is not recognized by our system as rape….

[Nurse, Female 39-year-old, Casualty]

3.2.2. Improved Attitudes towards Survivors

The training changed the attitudes of HCPs towards women affected by violence by making them more empathetic in recognizing the barriers faced by women in disclosing violence. It also enabled providers to better recognize how they could play a role in overcoming those barriers and supporting women to disclose. HCPs listed the following factors as reasons why women experiencing violence may not disclose in a healthcare setting: stigma, family pressure, the honor of family, the socialization of women, the financial dependence of women, and a lack of awareness about the availability of services. They also listed facility-level barriers, such as a lack of trust in the HCP, feeling unsafe in the facility, and fear of what would happen if she discloses. As one respondent explained:

This is to do with our socialization. From childhood we have been taught that marriage is sacred…there is no acceptance of separated and divorced women by our society. That’s why women keep on tolerating and don’t share their problems.

[Doctor, Male, 27-year-old, Medicine]

Another training participant noted:

She is scared….if she will file a case against her husband, then where will she go? She is completely dependent on her husband. What will happen to my children?…how we will they survive in the future? These are her concerns….due to this, the women don’t come forward.

[Nurse, Female, 38-year-old, Casualty]

The training supported shifts in the attitudes of HCPs towards a greater willingness to encourage women to disclose violence, including by building rapport, asking women about the situation at home through indirect questions, providing privacy, ensuring confidentiality, and providing support.

Most women easily disclose it when we ask them politely. But there are also some women who hesitate to share anything. I think it is important to be receptive to such women, assure them that we are there to help her and validate her feelings.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

The HCPs indicated that the training helped them understand the importance of respecting women’s autonomy and choices. The respondents indicated that the training had made them sensitive to the concerns and predicament of young girls and their lack of agency within their families. One respondent explained:

We listen to her…we don’t judge her and give her suggestions….but ultimately she only has to decide what she wants to do.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

Another respondent highlighted the importance of respecting women’s wishes to not disclose and reassuring her of confidentiality.

We should assure her that whatever she will tell us it will not be shared with anyone, we should tell her that we understand her problem and will not force her to do something which she doesn’t want to do.

[Nurse, Female, 51-year-old, OBGY]

3.2.3. Improved Confidence and Skills in Inquiring about Violence

All HCPs said that they felt more confident in being able to respond to women affected by violence following the training. Most respondents stated that they had identified and provided care and support to a minimum of two to three women daily since they had participated in the training. One respondent stated:

I feel confident. My skills have improved over time. It has now become part of my routine practice and it is integrated into my practice.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

A doctor explained:

Now, whenever I examine a female patient and I have even a little doubt that the woman might be facing trouble….I don’t hesitate to ask her about her problems. This point always stay in my mind that we have to ask the woman.

[Doctor, Male, 27-year-old, Medicine]

The respondents felt that they had the skills to carefully inquire about violence, when needed. In situations where a woman was not disclosing violence on her own, the HCPs reported a range of strategies for providing encouragement and support to women who they suspected to be experiencing violence. For example, HCPs reported asking about violence in an examination room away from the outpatient department, where relatives of the women and other patients are sitting, using language such as:

I am concerned about you. You are my patient … not your husband … not your family. I am concerned about your health.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

If women did not disclose violence, the respondents informed them that they can come back to the clinic and speak about it whenever they were comfortable. This indicates that the training helped them to not impose their views on women, to listen to women attentively, to not interrupt them, and to build trust and rapport. The respondents noted that they had learned skills regarding carefully and empathetically asking about violence. One nurse explained:

I am not saying that if we will ask her then she will quickly tell us everything. No…for years she has not shared it with anyone then how will she tell us immediately. We have to make efforts for this. We need to ask her politely: Do you have any trouble? Why are you looking so sad” …then only she will open up.

[Nurse, Female, 57-year-old, OBGY]

Several other respondents indicated that the training had been instrumental in improving ways of asking about violence. One doctor noted,

I ask them about the situation at home. How much income is there? How many children are there? How is the situation at their maternal home? Are they supportive? Gradually, I ask them about any problem at home, how is her relationship with husband, in laws….

[Doctor, Male, 59-year-old, Medicine]

3.2.4. Improved Skills Regarding Offering Clinical Care

First-line support, which is a key aspect of care provision that is emphasized during the training using the job aid LIVES, appeared to be particularly relevant to HCPs. For example, all five steps of LIVES—Listen, Inquire about needs and concerns, Validate, Enhance safety, and facilitate Support—were consistently discussed by HCPs. All HCPs responded that they were able to listen with empathy and inquire about their needs and concerns. However, the HCPs did not explicitly mention offering validating responses in their recall of using LIVES to provide first-line support.

One doctor emphasized the role of listening as a first step:

Yes—LIVES meaning we had been told, that foremost you have to listen. You have to listen to her points calmly…You should not put your own agenda before them. Meaning the points that she is making, that you can change these points in your way of living, and in the end give her your suggestion. But don’t impose, just suggest to her, that from between these two you can choose. Then she herself will say that I will make this choice. I like the aspect of Listen. If you listen to her calmly the woman starts revealing.

[Doctor, Female, 25-year-old, OBGY]

The HCPs also discussed approaches towards enhancing safety through providing referrals. Facilitating social support was also identified as a key element of first-line support. The HCPs gave examples of ways in which they facilitated support for women thrown out of their marital homes. Some mentioned referrals to shelters. Providers frequently mentioned referring survivors to the social worker or giving the telephone number of the Protection Officer. The HCPs discussed referring a few women to police stations, and, in some cases, women were allowed to stay longer at the hospital in lieu of the shelter so that they could remain safe.

If we feel that it is a woman facing domestic violence, and she won’t be taken care of well at home, we extend her admission till she recovers completely from her illness. we ensure the provision of high protein diet. we have also sometimes secured medicines for her for a month so that her health can get better.

[Doctor, Male, 49-year-old, OBGY]

A doctor shared his perspective on the role of first-line support:

When woman comes to hospital, we are the first point of contact. When we suspect that violence is there, we provide emotional support to woman. Due to this emotional support, the woman opens up and shares her problems. So, providers are actually providing emotional support while identification. If this support will not be there then women will not open up.

[Doctor, Male, 42-year-old, OBGY]

These findings highlight that the training content and approaches are relevant in building knowledge and understanding of the health aspects of VAW and of their own role. In addition, the content and approaches also reoriented the providers’ attitudes towards rights-based approaches that respect the autonomy of women and also built clinical skills regarding inquiring and to listening to women with empathy and offering practical and emotional support to survivors.

3.3. Barriers and Enablers Regarding Providing Care to Survivors

3.3.1. Infrastructure in Relation to Privacy and Confidentiality

The HCPs reported that the location and space within the facilities posed a barrier or could enable their ability to inquire about violence. For example, several respondents explained that women cannot speak in the presence of other members or even other patients and that, therefore, the creation of a private space was important. Solutions to privacy were described by respondents working in different departments. For example, in the out-patient department, women were asked to step into another room to continue a discussion so that the family members accompanying them could remain outside. Some providers explained that they find it more suitable to ask about violence in in-patient settings when women are admitted to the hospital than in the out-patient services. This is because women who are admitted to the in-patient department are by themselves and without their family, enabling more time for HCPs to establish rapport and speak with them. As one doctor noted,

In the outpatient department [OPD], there are 80 to 100 patients and in three to four hours we have to see all of them. This is the limitation in OPD. In the ward [in patient], we have multiple opportunities to interact with patients. There are nurses, junior residents and senior residents who interact with them on daily basis. So, in the in-patient department it is easier to do identification.

[Doctor, Male, 49-year-old, OBGY]

Another doctor explained his strategies for ensuring the right to private consultation:

One of the biggest challenges is talking to women in medicine outpatient department where 20 to 25 people are standing there inside the outpatient department at one time. In cases where I suspect violence, I take the woman to a separate room for asking about violence and if there are lots of patients then I ask the sister (nurse) to talk to the woman.

[Doctor, Male, 26-year-old, Medicine]

In the FGDs, the respondents noted that while privacy and confidentiality can easily be ensured in in-patient wards, it was more difficult to ensure these things in outpatient clinics due to overcrowding. Therefore, the providers needed to be more creative in finding ways to talk to women privately in the outpatient clinics. The respondents indicated that, due to the training, they knew to inform women that their discussions would not be divulged to anyone. One respondent gave an example of how they addressed inquiries from family members about the lengthy patient consultation:

I just tell relatives that I was counseling patient about her health and diet. I don’t tell them about actual conversation. Otherwise, they can harm the patient. So, I try my best to maintain confidentiality. This is important otherwise woman will never share her problems with anyone.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, Medicine]

3.3.2. Supporting the Health Workforce

Understaffing and a Lack of Dedicated Staff for Responding to VAW

The training intervention was delivered in a way that emphasized the integration of responses to VAW as part of routine clinical care. The training discussed strategies on how to maximize the limited time and interactions with women to triage and task-share with colleagues in the team. Despite this, in a large-patient-volume, limited-health-workforce context, workloads and a lack of time were found to be a challenge. Some respondents indicated that they had sufficient time to ask women that they suspected if they were experiencing violence. These respondents indicated that they were able to ask about abuse while they were taking medical history or conducting a physical examination. Other respondents indicated that having sufficient time to inquire about violence was an ongoing challenge. One doctor, when asked about the most significant barrier in implementing what he had learned in the training, explained:

Lack of time is the biggest problem! So much work is there in the government hospitals! Patient load remains too high. But still providers who are interested will take out time for this. Therefore, it is important to change the way people look at this issue.

[Doctor, Male, 59-year-old, Medicine]

The respondents indicated the need for an additional health workforce and a dedicated social worker in each department to address the issues of a high workload. One doctor indicated:

There should be more staff members in the department…the medicine department is highly understaffed. We need more people…both doctors and nurses.

[Doctor, Male, 26-year-old, Medicine]

Importance of Teamwork, Champions, Supportive Supervision, Mentoring, and Job Aids

The respondents indicated that supportive supervision was a critical factor for integrating VAW responses into their routine clinical practice. To have senior clinicians and administrators who were sensitive to the issue and trained to provide a standard of care to survivors of violence was seen as a motivator and enabler for other HCPs to do the same. Senior clinicians who had participated in the training were very supportive of HCPs, using their skills and knowledge from the training. They acted as champions for integrating VAW responses into clinical practice. Some participants indicated that the heads of departments who had not participated in the training were not adequately supportive. One doctor explained:

There were challenges in this context. The heads of department give no importance to such topics. If there is training on echo-cardiography then the head of department will make sure to follow with every resident to ensure that whether they have registered for it or not. But they don’t give importance to issue of VAW and consider it a social issue where they perceive that providers can’t do anything.

[Doctor, Male, 59-year-old, Medicine]

The respondents also highlighted that the team approach and shared responsibilities for caring for survivors were enabling factors. As noted by several providers below:

If I identify any woman facing violence during OPD then I have my colleagues who can facilitate further procedures like contacting social worker and providing support services to woman. Also, if I feel that woman is not feeling comfortable in sharing her problems with a male doctor then also I call sister from our department.

[Doctor, Male 27-year-old, Medicine]

Our social workers have become more active. Earlier, they used to intervene only in cases where patients need medical aid but now they are helping women facing violence as well.

[Doctor, Male, 59-year-old, Medicine]

So, we organize a discussion every month or whenever it is possible about the cases, any difficulties, challenges and doubts faced by staff members. These meeting are really helpful to appreciate and encourage staff members who are actively working on this issue.

[Doctor, Male, 42-year-old, OBGY)

Addressing the Mental Well-Being of the Health Workforce

Almost all of the HCPs acknowledged that listening to the histories of violence is disturbing for them. These stories force them to question what is happening in society regarding the pain being inflicted on women. Some felt sad and hopeless. A nurse noted:

I feel very sad……the world has progressed so much and still violence is happening, and women are suffering. I keep on thinking about the woman’s life… for several days.

[Nurse, Female, 42-year-old, OBGY]

Some HCPs indicated that they were able to access psychological support from colleagues and department heads. They highlighted that such support was helpful for maintaining well-being in the face of such challenging work. One nurse explained:

I think talking to our colleagues and discussing cases with them can be helpful….and if some staff member is feeling a lot of stress about all this then seniors from the department can talk and motivate staff.

[Nurse, Female, 56-year-old, Nursing administrator]

While stories of violence faced by women were distressing for some HCPs, others reported that providing support to women made them feel motivated. For example, a doctor described:

I feel inspired—it feels that these women are ready to fight and we are there to help them. I don’t get frustrated while handling such cases.

[Doctor, Female, 26-year-old, OBGY]

Some providers reported that their burden of a high workload was somewhat mitigated by their sense of duty towards women experiencing violence. As a doctor explained:

HCPs may face burn-out in the face of these pressures, but we have a stronger feeling that this our duty.

[Doctor, Male, 59-year-old, Medicine]

To address issues of burnout and the need for HCPs’ support, some HCPs suggested more structured forms of support—for example, a nurse recommended that there could be workshops for discussing HCPs’ experiences of handling cases of VAW. Others largely reported informal means of support through colleagues and family members as being useful.

Referrals and Outreach with Other Community Services

While the health sector is an important entry point, it is important to have other community or sectoral support services in order to meet the broader needs of survivors, and ensuring linkages and coordination with these services remained a challenge. The respondents consistently discussed challenges with a lack of referral networks. The providers expressed concern and discomfort about the inability to provide any specific support or not knowing what happens to a survivor when she leaves the facility. The HCPs reported not knowing what happens when women are referred elsewhere, as there is no way to follow up. One doctor noted:

We were given the contact number of various organizations where we referred women. But we don’t know whether the women reached there, or did she get any help? Was it useful for her? We don’t have any such information.

[Doctor, Male, 26-year-old, Medicine]

Many respondents indicated that this issue could be addressed by having a designated person at the facility level who is trained in the provision of counseling and support and is responsible for following up with each woman. One doctor explained that women are told:

You speak to this person, speak to that person, and they had also given an address. Women are given 2 numbers and told that they [referral providers] could be contacted on those (numbers)….[but the women] cannot travel so far to get help, and there was nothing in my hands. Having a person within our own institute will be good.

[Doctor, Female, 25-year-old, OBGY]

4. Discussion

These qualitative data indicate the relevance of the training methodology—in particular, that it was acceptable and feasible. The respondents perceived the training to be relevant in addressing the values, attitudes and norms that influenced their perception of their role in responding to VAW. The data suggest that the factors that contributed to the acceptability and feasibility of the training were linked to using a participatory approach and to having content that focused on a clear set of competencies related to generating knowledge and understanding of VAW as a public health problem, the role of healthcare providers, the importance of centering care around rights-based approaches, and practical skills regarding empathetic listening and the provision of clinical care interventions such as first-line support using job aids such as LIVES. The findings reinforce the recommendations of the health systems approach to addressing VAW, highlighting the importance of strengthening the health workforce through training and capacity-building approaches that are participatory, that involve supervision and mentoring from senior clinicians, and where training is not a one-off activity but is rather ongoing and integrated into existing curricula.

The data indicate a shift towards a greater understanding of VAW as a health issue, of the signs and symptoms that are indicative of violence, and of the legal mandate for health professionals to care for women affected by violence in India. Training helped create and sustain a perception of VAW as a health issue, providing a justification for HCPs’ role in responding to VAW and enabling them to see addressing VAW as intertwined with addressing physical symptoms.

The qualitative data on the providers’ perceptions also complement and reinforce some of the quantitative findings of a survey on the providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices reported elsewhere [

22], contextualizing what barriers and enablers explained the changes in the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of providers. For example, the qualitative findings also indicate changes in HCP attitudes towards addressing VAW—for example, a recognition of women’s lack of autonomy within their family context and stigma as barriers to disclosure, different types of violence faced by women, and being more understanding of women’s circumstances. These shifts allowed HCPs to feel more confident about listening to women with more empathy.

The shifts in knowledge and attitudes regarding addressing VAW are reflected in other literature on HCP responses to women affected by violence, which similarly highlight that a willingness to view VAW as a public health issue contributes to more support for women affected by violence in their clinical practice [

33]. A recent qualitative meta-analysis identified personal beliefs and values surrounding VAW and beliefs that addressing VAW is beyond the purview of HCPs’ responsibilities, including not recognizing VAW as a public health issue, as major barriers to HCPs addressing VAW in their work [

34]. Sustained changes to social and gender norms, however, particularly for HCPs who still live and work in communities with high levels of normalization of violence against women, require on-going support and intervention [

35,

36].

In our study, HCPs also identified a number of health-system-level factors that either enabled or limited their capacity to provide quality care for women affected by violence. The enablers and barriers could be categorized as follows: those related to infrastructure that either enabled or impeded the ability to have private and confidential consultations with survivors, health workforce factors related to understaffing and high workloads leading to limitations on their time, teamwork, support from senior management supervision, mentoring, and championship could be categorized as enablers, and the weak multisectoral linkages with other community and support services resulting in limited referral services could be categorized as barriers. As the literature on the health response to VAW has noted, training providers alone is not enough; our findings reinforce this, as creating space to ensure privacy and confidentiality for women was an important system-level factor reported by providers as enabling responding to VAW. Evidence that training alone is not sufficient but requires health system changes has been reflected in the global evidence base, and this evidence was used to inform the recommendations of the WHO clinical and policy guidelines that were the basis for this intervention and study [

12]. In line with this global body of evidence, the interventions in this study described elsewhere [

37] also included health system strengthening components, focusing on infrastructure changes, supportive supervision, mentoring, documentation systems, and the creation of champions. Our findings reflect that the training along with the system strengthening components had some positive impacts. However, it is not easy to completely address system-level barriers with a micro-intervention such as this, as these broader shifts require shifts in hospital management and human resource policies. This would be the case with any type of new clinical intervention that is introduced within existing systems. In the ideal world, there would be more human resources in terms of dedicated staff for responding to VAW. However, given that health worker shortages are a reality in most LMIC countries [

38], this may not always be possible. Despite this, we have highlighted that, even with the limited existing human resources, it is possible to respond to women affected by violence within a healthcare setting.

To address the limited health workforce dedicated to responding to VAW, the HCPs in our study suggested that departments or hospitals have designated staff for providing support services and following up with women in order to improve the quality of care. There is evidence that having dedicated staff to enhance follow-ups with women, including regarding the outcomes of the care they received, can motivate providers and reinforce what all HCPs could do in responding to survivors [

39]. There is also evidence that having supportive supervision and mentoring and applying a teamwork approach when new areas of clinical practice are introduced are important enablers for uptake and sustaining changes in HCPs’ behavior, along with job aids and IEC materials for both HCPs and patients [

4]. The findings related to referral services also resonate with the literature which indicates that HCPs in LMICs often feel that, due to lack of established referrals and networks with other services, they are unable to provide adequate support to women who do disclose or who they identify [

40,

41].

Health system readiness to implement interventions to address VAW within the health system is essential to comprehensively improving the health sector response to VAW and is well recognized and recommended as the standard approach in the WHO guidelines [

12,

42]. The key elements of health system readiness include having Standard Operating Protocols (SOPs) to guide service delivery, leadership champions, infrastructure that enables privacy and confidentiality, coordination with other sector services through referral linkages, and information and evidence including through the documentation of VAW in the health management information system. The qualitative data reinforce the importance of system readiness factors as either enablers or barriers.

The study also had some limitations. Despite having a high number of interviews and FGDs, we did not formally assess data saturation, which can be considered a limitation. However, given that our healthcare provider sample is drawn from three hospitals and three departments and that we covered participants representing these different departments and hospitals, we are confident that our sample size and coding likely reached saturation given the relative homogeneity of the participant population. We only included HCPs working in tertiary care facilities, and their perspectives on and experiences of the training and the implementation of new skills and procedures may not be easily generalized to primary health facilities, which function with even fewer human and financial resources than tertiary care facilities. The perspectives of HCPs working at primary and secondary healthcare facilities are important to capture, and in future phases of this research, we plan to implement and document health system intervention that includes the training of HCPs at the primary healthcare level.