Out-of-State Travel for Abortion among Texas Residents following an Executive Order Suspending In-State Services during the Coronavirus Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

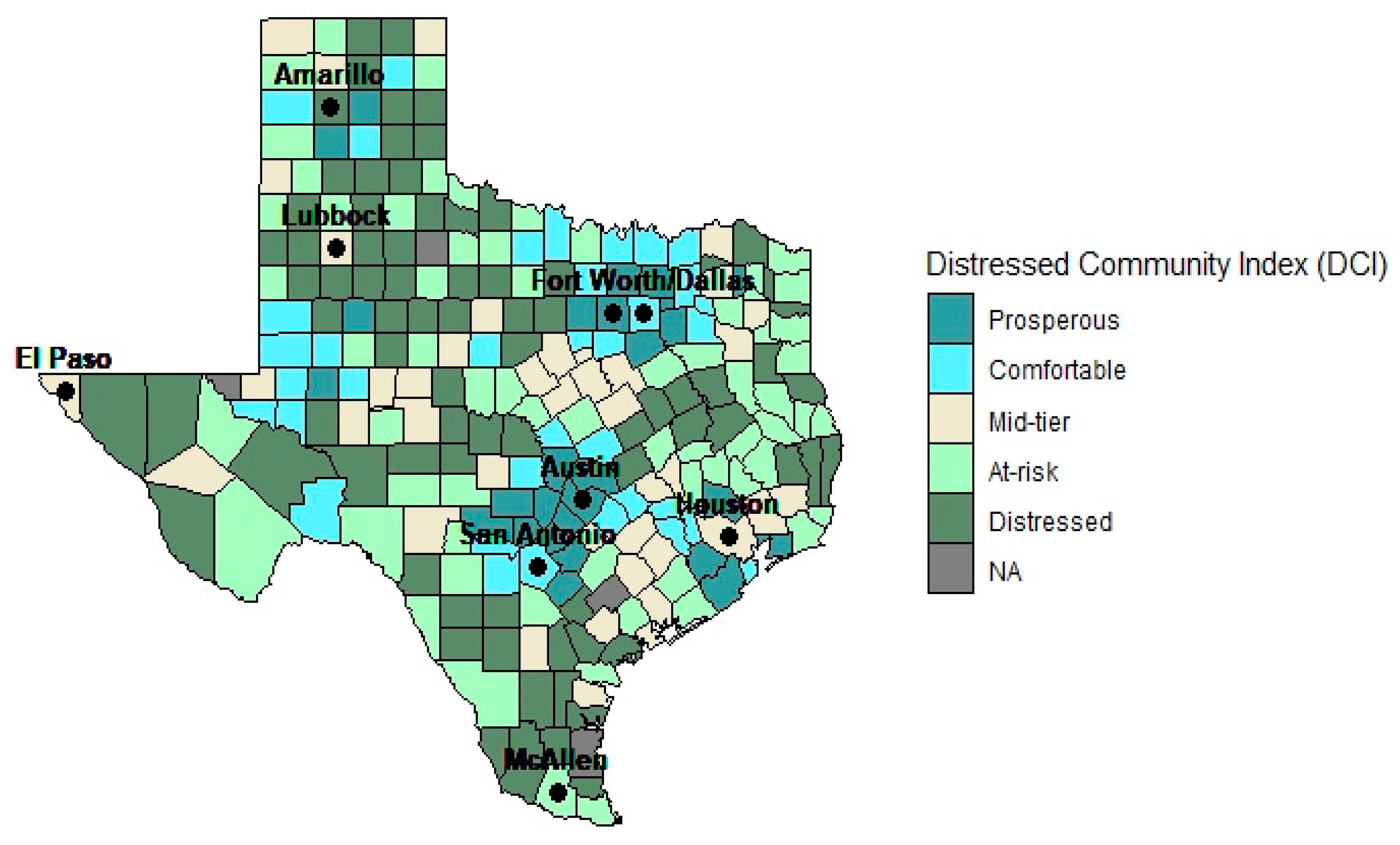

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Time Trends in Out-of-State Abortion Care

2.3.2. Geographic Flows and Travel Distance

3. Results

3.1. Time Trends in Out-of-State Abortions

3.2. Geographic and Travel Distance Patterns in Out-of-State Abortions

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Webber, M. How Coronavirus Is Changing Access to Abortion. Politico. 2020. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/how-coronavirus-is-changing-access-to-reproductive-health/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Endler, M.; Al-Haidari, T.; Benedetto, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Christilaw, J.; El Kak, F.; Galimberti, D.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Gutierrez, M.; Ibrahim, S.; et al. How the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights and response: Results from a global survey of providers, researchers, and policy-makers. Acta Obs. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, L.; Ramaswamy, A.; Frederiksen, B.; Salganicoff, A. State Action to Limit Abortion Access during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-action-to-limit-abortion-access-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Abbott, G. Executive order GA 09: Relating to Hospital Capacity During the COVID-19 Disaster. 2020. Available online: https://gov.texas.gov/uploads/files/press/EO-GA_09_COVID-19_hospital_capacity_IMAGE_03-22-2020.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Paxton, K. Health Care Professionals and Facilities, including abortion Providers, Must Immediately Stop All Medically Unnecessary Surgeries and Procedures to Preserve Resources to Fight COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/news/releases/health-care-professionals-and-facilities-including-abortion-providers-must-immediately-stop-all (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Joint Statement on Abortion Access during the COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020. Available online: https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2020/03/joint-statement-on-abortion-access-during-the-covid-19-outbreak (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Roberts, S.C.M.; Berglas, N.F.; Schroeder, R.; Lingwall, M.; Grossman, D.; White, K. Disruptions to abortion care in Louisiana during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.; Kumar, B.; Goyal, V.; Wallace, R.; Roberts, S.C.M.; Grossman, D. Changes in abortion in Texas following an executive order ban during the coronavirus pandemic. JAMA 2021, 325, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, B.J.; Lock, L.; Parks, V.; Anderson, B.; Cathey, J.R. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Access to Abortion. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 138, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, S.; Joyce, T. Regulating abortion: Impact on patients and providers in Texas. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2011, 30, 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raifman, S.; Sierra, G.; Grossman, D.; Baum, S.E.; Hopkins, K.; Potter, J.E.; White, K. Border-state abortions increased for Texas residents after House Bill 2. Contraception 2021, 104, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Sierra, G.; Lerma, K.; Beasley, A.; Hofler, L.G.; Tocce, K.; Goyal, V.; Ogburn, T.; Potter, J.E.; Dickman, S.L. Association of Texas’ 2021 ban on abortion in early pregnancy with the number of facility-based abortions in Texas and surrounding states. JAMA 2022, 328, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, E.; Guarnieri, I. Six Months Post-Roe, 24 US States Have Banned Abortion or Are Likely to Do So: A Roundup; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/2023/01/six-months-post-roe-24-us-states-have-banned-abortion-or-are-likely-do-so-roundup (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Economic Innovation Group. The Distressed Communities Index; Economic Innovation Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://eig.org/distressed-communities/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Huber, S.; Rust, C. Calculate travel time and distance with OpenStreetMap data using the Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM). Stata J. 2016, 16, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagner, A.; Soumerai, S.; Zhang, F.; Ross-Degnan, D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002, 27, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Dane, A.; Vizcarra, E.; Dixon, L.; Lerma, K.; Beasley, A.; Potter, J.; Ogburn, T. Out-of-State Travel for Abortion Following Implementation of Texas Senate Bill 8; Texas Policy Evaluation Project. 2022. Available online: http://sites.utexas.edu/txpep/files/2022/03/TxPEP-out-of-state-SB8.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Carpenter, E.; Burke, K.L.; Vizcarra, E.; Dane’el, A.; Goyal, V.; White, K. Texas’ Executive Order during COVID-19 Increased Barriers for Patients Seeking Abortion Care. Texas Policy Evaluation Project. Available online: http://sites.utexas.edu/txpep/files/2020/12/TxPEP-research-brief-COVID-abortion-patients.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Aiken, A.R.A.; Starling, J.E.; Gomperts, R.; Tec, M.; Scott, J.G.; Aiken, C.E. Demand for self-managed online telemedicine abortion in the United States during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Obs. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 835–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.C.M.; Schroeder, R.; Joffe, C. COVID-19 and Independent Abortion Providers: Findings from a Rapid-Response Survey. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2020, 52, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.; Jerman, J. Distance traveled to obtain clinical abortion care in the United States and reasons for clinic choice. J. Women’s Health 2019, 28, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heymann, O.; Odum, T.; Norris, A.H.; Bessett, D. Selecting an abortion clinic: The role of social myths and risk perception in seeking abortion care. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2022, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, U.D.; Ahlbach, C.; Kaller, S.; Cook, C.; Muñoz, I. Trends in self-pay charges and insurance acceptance for abortion in the United States, 2017–2020. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmacher Institute. Abortion Policy in the Absence of Roe; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/abortion-policy-absence-roe (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Jones, R.K.; Philbin, J.; Kirstein, M.; Nash, E. New Evidence: Texas Residents Have Obtained Abortions in at Least 12 States That Do Not Border Texas; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2021/11/new-evidence-texas-residents-have-obtained-abortions-least-12-states-do-not-border (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- White, K.; Vizcarra, E.; Palomares, L.; Dane’el, A.; Beasley, A.; Ogburn, T.; Potter, J.; Dickman, S. Initial Impacts of Texas’ Senate Bill 8 on Abortions in Texas and at Out-of-State Facilities. Texas Policy Evaluation Project. 2021. Available online: http://sites.utexas.edu/txpep/files/2021/11/TxPEP-brief-SB8-inital-impact.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Myers, C.; Jones, R.K.; Upadhyay, U.D. Predicted changes in abortion access and incidence in a Post-Roe world. Contraception 2019, 100, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, U.D.; Desai, S.; Zlidar, V.; Weitz, T.; Anderson, P.; Taylor, D. Prevalence of abortion complications and incidence of emergency room visits among 55,000 abortions covered by the California Medi-Cal program. Contraception 2013, 88, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martuscelli, C. The Plan to Overturn Abortion Rights in Europe. Politico. 2022. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/roe-vs-wade-us-the-european-activists-taking-inspiration-and-money-from-us-anti-abortion-groups/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Zampana, G. Italy’s Politics Gives New Life to Anti-Abortion Campaign. Politico. 2018. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/italy-abortion-divide-politics-gives-new-life-to-anti-abortion-campaign/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- De Zordo, S.; Zanini, G.; Mishtal, J.; Garnsey, C.; Ziegler, A.K.; Gerdts, C. Gestational age limits for abortion and cross-border reproductive care in Europe: A mixed-methods study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnsey, C.; Zanini, G.; De Zordo, S.; Mishtal, J.; Wollum, A.; Gerdts, C. Cross-country abortion travel to England and Wales: Results from a cross-sectional survey exploring people’s experiences crossing borders to obtain care. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L. Inequity in US Abortion Rights and Access: The End of Roe Is Deepening Existing Divides. Guttmacher Institute. 2023. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/2023/01/inequity-us-abortion-rights-and-access-end-roe-deepening-existing-divides (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Mexico’s Quintana Roo State Decriminalises Abortion. Al Jazeera. 2022. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/10/26/mexicos-quintana-roo-state-decriminalises-abortion (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Giorgio, M.; Makumbi, F.; Kibira, S.P.; Bell, S.O.; Chiu, D.W.; Firestein, L. An investigation of the impact of the Global Gag Rule on women’s sexual and reproductive health outcomes in Uganda: A difference-in-differences analysis. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2022, 30, 2122938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sully, E.A.; Shiferaw, S.; Seme, A.; Bell, S.O.; Giorgio, M. Impact of the Trump Administration’s Expanded Global Gag Rule Policy on Family Planning Service Provision in Ethiopia. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2022, 53, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Trump, trans students and transnational progress. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Before Order was Issued (1 February–21 March) | While Order was in Effect (22 March–21 April) | After Order Expired (22 April–31 May) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Texas residents, n | 315 | 889 | 341 |

| Facility where received care, n (%) *** | |||

| Went to nearest out-of-state facility | 174 (55.2) | 75 (8.4) | 100 (29.3) |

| Did not go to nearest facility | 137 (43.5) | ||

| Service disruptions at nearest | -- | 614 (69.1) | 127 (37.2) |

| No service disruptions at nearest | -- | 186 (20.9) | 112 (32.9) |

| Missing | 4(1.3) | 14(1.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| County-level economic deprivation, n (%) *** | |||

| Distressed | 37 (11.8) | 30 (3.4) | 35 (10.3) |

| At-risk | 125 (39.7) | 72 (8.1) | 69 (20.2) |

| Mid-tier | 74 (23.5) | 178 (20.0) | 85 (24.9) |

| Comfortable | 35 (11.1) | 263 (29.6) | 64 (18.8) |

| Prosperous | 40 (12.6) | 333 (37.4) | 86 (25.2) |

| Missing | 4(1.3) | 13(1.5) | 2(0.6) |

| One-way distance traveled, miles, n (%) | |||

| <250 | 192 (61.0) | 170 (19.1) | 130 (38.1) |

| 250–499 | 71 (22.5) | 318 (35.8) | 111 (32.6) |

| ≥500 | 48 (15.2) | 388 (43.6) | 98 (28.7) |

| Missing | 4(1.3) | 13(1.5) | 2(0.6) |

| Abortion type & gestational duration, n (%) | |||

| Medication | 72 (22.9) | 455 (51.2) | 125 (36.7) |

| Procedure, ≤11 wks | 134 (42.5) | 214 (24.1) | 104 (30.5) |

| Procedure, 12–15 wks | 48 (15.2) | 106 (11.9) | 49 (14.4) |

| Procedure, 16–21 wks | 22 (7.0) | 89 (10.0) | 30 (8.8) |

| Procedure, ≥22 wks | 39 (12.4) | 23 (2.6) | 32 (9.3) |

| Missing | 0(0.0) | 2(0.2) | 1(0.3) |

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 3 c | Model 4 d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order Implementation & Expiration Not Lagged | Order Implementation Lagged | Order Expiration Lagged | Order Implementation & Expiration Lagged | |||||

| IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | |

| Baseline weekly trend prior to implementation of executive order e | 1.01 | (0.96, 1.06) | 1.04 | (0.99, 1.10) | 1.01 | (0.97, 1.06) | 1.03 | (0.98, 1.09) |

| Implementation of executive order f | 1.14 | (0.49, 2.63) | 3.64 | (2.13, 6.21) | 1.91 | (0.57, 6.37) | 4.41 | (2.39, 8.14) |

| Weekly trend after implementation of the executive order g | 1.64 | (1.23, 2.18) | 1.10 | (0.89, 1.34) | 1.29 | (0.89, 1.88) | 0.99 | (0.78, 1.26) |

| Expiration of the executive order h | 0.55 | (0.32, 0.95) | 0.74 | (0.46, 1.17) | 0.27 | (0.08, 0.90) | 0.47 | (0.26, 0.86) |

| Weekly trend after the expiration of the executive order i | 0.44 | (0.33, 0.59) | 0.63 | (0.49, 0.80) | 0.61 | (0.41, 0.90) | 0.77 | (0.60, 1.00) |

| Before Order Was Issued (1 February–21 March) | While Order was in Effect (22 March–21 April) | After Order Expired (22 April–31 May ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 315 | N = 889 | N = 341 | |

| Health Service Region | |||

| Panhandle (Lubbock) | 54 (17.1) | 50 (5.6) | 71 (20.8) |

| North Central (Dallas/Ft. Worth) | 54 (17.1) | 398 (44.8) | 103 (30.2) |

| East (Tyler) | 165 (52.4) | 54 (6.1) | 81 (23.7) |

| Southeast (Houston) | 13 (4.1) | 170 (19.1) | 28 (8.3) |

| Central (Austin) | 3 (1.0) | 109 (12.2) | 20 (5.8) |

| South Central (San Antonio) | 4 (1.3) | 63 (7.1) | 10 (2.9) |

| West (El Paso) | 16 (5.1) | 24 (2.7) | 19 (5.6) |

| South (Harlingen/McAllen) | 2 (0.6) | 8 (0.9) | 7 (2.1) |

| Missing | 4(1.3) | 13(1.5) | 2(0.6) |

| Destination State | |||

| Arkansas | 1 (0.3) | 48 (5.4) | 11 (3.2) |

| Colorado | 5 (1.6) | 131 (14.7) | 28 (8.2) |

| Kansas | 1 (0.3) | 222 (25.0) | 18 (5.3) |

| Louisiana | 172 (54.6) | 91 (10.2) | 101 (29.6) |

| New Mexico | 105 (33.3) | 271 (30.5) | 137 (40.2) |

| Oklahoma | 31 (9.8) | 126 (14.2) | 46 (13.5) |

| Median Distance (IQR) to Facility where Received Care | Median Distance (IQR) beyond Nearest Facility | |

|---|---|---|

| Facility where received care *** | ||

| Went to nearest out-of-state facility | 189.2 (97.8, 239.8) | 155.2 (0, 239.2) |

| Did not go to nearest facility | ||

| Service disruptions at nearest | 468.0 (334.8, 736.6) | 442.7 (305.6, 706.1) |

| No service disruptions at nearest | 403.2 (334.0, 695.1) | 360.1 (218.5, 678.0) |

| County-level economic deprivation *** | ||

| Distressed | 289.4 (285.4, 413.4) | 46.5 (27.1, 179.9) |

| At-risk | 304.2 (120.4, 673.2) | 186.0 (9.2, 622.6) |

| Mid-tier | 450.1 (304.1, 884.0) | 444.4 (239.2, 883.4) |

| Comfortable | 381.1 (324.1, 652.9) | 360.1 (309.8, 646.7) |

| Prosperous | 402.7 (334.0, 695.1) | 381.6 (305.6, 688.9) |

| Abortion type & Gestational duration *** | ||

| Any abortion, ≤11 wks | 384.2 (279.2, 693.6) | 360.1 (204.1, 683.4) |

| Procedure, 12–15 wks | 366.3 (334.0, 650.0) | 360.1 (247.6, 631.4) |

| Procedure, 16–21 wks | 627.0 (366.3, 811.0) | 617.8 (348.7, 716.4) |

| Procedure, ≥22 wks | 688.6 (648.9, 854.8) | 9.9 (9.9, 9.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sierra, G.; Berglas, N.F.; Hofler, L.G.; Grossman, D.; Roberts, S.C.M.; White, K. Out-of-State Travel for Abortion among Texas Residents following an Executive Order Suspending In-State Services during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043679

Sierra G, Berglas NF, Hofler LG, Grossman D, Roberts SCM, White K. Out-of-State Travel for Abortion among Texas Residents following an Executive Order Suspending In-State Services during the Coronavirus Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043679

Chicago/Turabian StyleSierra, Gracia, Nancy F. Berglas, Lisa G. Hofler, Daniel Grossman, Sarah C. M. Roberts, and Kari White. 2023. "Out-of-State Travel for Abortion among Texas Residents following an Executive Order Suspending In-State Services during the Coronavirus Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043679