Shared Components of Worldwide Successful Sexuality Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sexuality Education Intervention Approaches

1.1.1. Abstinence Interventions

1.1.2. Comprehensive Interventions

1.1.3. Risk-Oriented Interventions

1.2. Additional Components of Sexuality Education Interventions for Adolescents

1.2.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2.2. Type of Intervention

1.2.3. Dose

1.2.4. Intervention Methodology

1.2.5. Facilitator’s Training

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- (1)

- Publication date: studies published from 2011 onwards.

- (2)

- Language: written in English or Spanish.

- (3)

- Intervention: Any combination of learning experiences aimed at developing a voluntary behavior leading to sexual health in adolescents [83]. The intervention had to be universal, preventive, targeted at adolescents (11 to 19 years old), and only include sex health-related topics (from the abstinence, risk-oriented, or comprehensive approach). This study included interventions that targeted strictly sex behavior (and not those that addressed exclusively related topics as partner violence or sexual abuse). Only in-person SEI interventions were included in this review because of the differences in emphasis and methodologies between in-person and remote health education interventions (e.g., physical activity attention to educational material; group interaction versus one-to-one accountability) [84,85,86]. For this review, we established two categories to define the type of intervention: (a) level of intervention (individual or group), and (b) sex of the participants (single-sex or mixed-sex groups).

- (4)

- Study design: experimental design (randomized control trial (RCT))

- (5)

- Intervention outcomes: intervention with at least one statistically significant positive outcome.

- (1)

- Not an empirical design: the study was a systematic review, protocol, or meta-analysis.

- (2)

- Not face-to-face intervention: the intervention was a remote (delivered completely or in part via the internet, a video, or a text message) or computer-based SEI.

- (3)

- Other participants: the intervention included parents or caregivers as active participants or was targeted at individuals with high risk in sex health.

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Risk of Bias and Assessment of Study Quality

2.5. Synthesis Method

3. Results

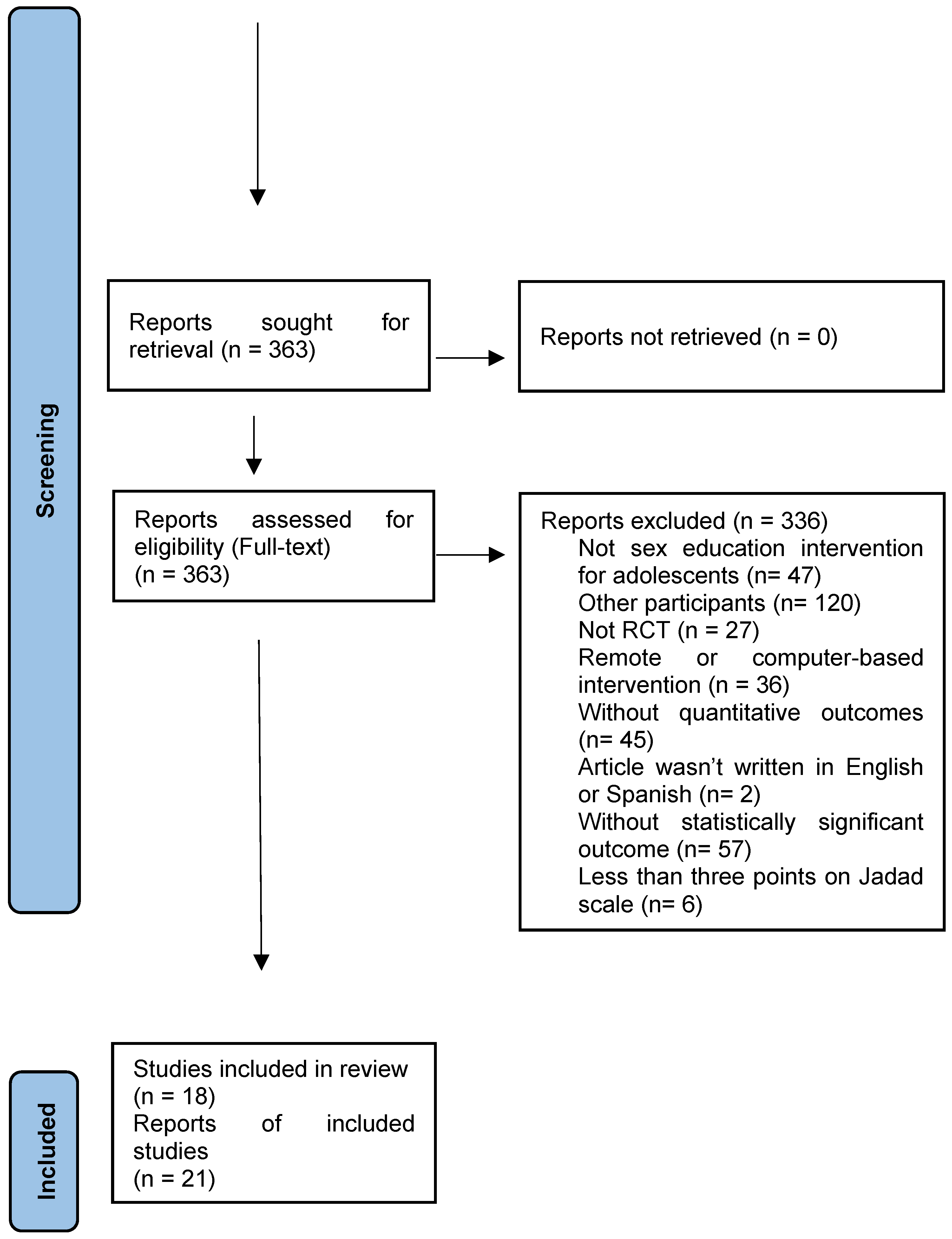

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. General Characteristics of the Interventions

3.3. Intervention Approach

3.4. Dose

3.5. Theoretical Frameworks

3.6. Type of Intervention

3.7. Intervention Methodology

3.8. Facilitator’s Training

3.9. Intervention Outcomes: Incidence on Health

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Defining Sexual Health–Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, D.; Junnarkar, M. Comprehensive Sex Education: Holistic Approach to Biological, Psychological and Social Development of Adolescents. Int. J. Sch. Health 2019, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilenko, S.A.; Lefkowitz, E.S.; Welsh, D.P. Is Sexual Behavior Healthy for Adolescents? A Conceptual Framework for Research on Adolescent Sexual Behavior and Physical, Mental, and Social Health. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2014, 2014, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2021: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Woog, V.; Singh, S.; Browne, A.; Philbin, J. Adolescent Women’s Need for and Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Developing Countries; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adimora, D.E.; Onwu, A.O. Socio-Demographic Factors of Early Sexual Debut and Depression among Adolescents. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 2634–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, C.; Temple, J.R.; Browne, D.; Madigan, S. Association of Sexting with Sexual Behaviors and Mental Health Among Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollett, N.; Cluver, L.; Bandeira, M.; Brahmbhatt, H. Identifying Risks for Mental Health Problems in HIV Positive Adolescents Accessing HIV Treatment in Johannesburg. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 29, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomicic, A.; Gálvez, C.; Quiroz, C.; Martínez, C.; Fontbona, J.; Rodríguez, J.; Aguayo, F.; Rosenbaum, C.; Leyton, F.; Lagazzi, I. Suicidio En Poblaciones Lesbiana, Gay, Bisexual y Trans: Revisión Sistemática de Una Década de Investigación (2004–2014). Rev. Med. Chil. 2016, 144, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, Q.; Usman, A.; Siddique, K.; Amjad, A. ‘Big Girls, Big Concerns’: Pubertal Transition and Psycho-Social Challenges for Urban Adolescent Females in Pakistan. Pak. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 40, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett, L.J.; Deardorff, J.; Johnson, M.; Irwin, C.; Petersen, A.C. Puberty Education in a Global Context: Knowledge Gaps, Opportunities, and Implications for Policy. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wight, D. Does Sex Education Make a Difference? Health Educ. 1997, 97, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Wight, D.; Raab, G.M.; Abraham, C.; Parkes, A.; Scott, S.; Hart, G. Impact of a Theoretically Based Sex Education Programme (SHARE) Delivered by Teachers on NHS Registered Conceptions and Terminations: Final Results of Cluster Randomised Trial. BMJ 2007, 334, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krebbekx, W. What Else Can Sex Education Do? Logics and Effects in Classroom Practices. Sexualities 2019, 22, 1325–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, L.D.; Maddow-Zimet, I.; Boonstra, H. Changes in Adolescents’ Receipt of Sex Education, 2006–2013. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vigil, P.; Riquelme, R.; Rivadeneira, H.; Aranda, W. TeenSTAR: Una Opción de Madurez y Libertad: Programa de Educación Integral de La Sexualidad, Orientado a Adolescentes. Rev. Med. Chil. 2005, 133, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacPherson, M.; Merry, K.; Locke, S.; Jung, M. Developing Mobile Health Interventions with Implementation in Mind: Application of the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) Preparation Phase to Diabetes Prevention Programming. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.R. Sex Education in the United States: Implications for Sexual Health and Health Policy. Corinthian 2020, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, H.B.; Sipe, T.A.; Elder, R.; Mercer, S.L.; Chattopadhyay, S.K.; Jacob, V.; Wethington, H.R.; Kirby, D.; Elliston, D.B.; Griffith, M.; et al. The Effectiveness of Group-Based Comprehensive Risk-Reduction and Abstinence Education Interventions to Prevent or Reduce the Risk of Adolescent Pregnancy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 272–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonjour, M.; van der Vlugt, I. Comprehensive Sexuality Education Knowledge File; Rutgers International: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fonner, V.A.; Armstrong, K.S.; Kennedy, C.E.; O’Reilly, K.R.; Sweat, M.D. School Based Sex Education and HIV Prevention in Lowand Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, K.; Operario, D.; Montgomery, P. Systematic Review of Abstinence-Plus HIV Prevention Programs in High-Income Countries. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, G.; Young, M. An Evaluation of an Abstinence-Only Sex Education Curriculum: An 18-Month Follow-Up. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, H.D. Advancing Sexuality Education in Developing Countries: Evidence and Implications. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2011, 14, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kemigisha, E.; Bruce, K.; Ivanova, O.; Leye, E.; Coene, G.; Ruzaaza, G.N.; Ninsiima, A.B.; Mlahagwa, W.; Nyakato, V.N.; Michielsen, K. Evaluation of a School Based Comprehensive Sexuality Education Program among Very Young Adolescents in Rural Uganda. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santelli, J.S.; Kantor, L.M.; Grilo, S.A.; Speizer, I.S.; Lindberg, L.D.; Heitel, J.; Schalet, A.T.; Lyon, M.E.; Mason-Jones, A.J.; McGovern, T.; et al. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heels, S.W. The Impact of Abstinence-Only Sex Education Programs in the United States on Adolescent Sexual Outcomes. Perspectives 2019, 11, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzetti, J.J. Sexuality Education: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. In Evidence-Based Approaches to Sexuality Education. A Global Perspective; Ponzetti, J.J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Panchaud, C.; Keogh, S.C.; Stillman, M.; Awusabo-Asare, K.; Motta, A.; Sidze, E.; Monzón, A.S. Towards Comprehensive Sexuality Education: A Comparative Analysis of the Policy Environment Surrounding School-Based Sexuality Education in Ghana, Peru, Kenya and Guatemala. Sex Educ. 2018, 19, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haberland, N. The Case for Addressing Gender and Power in Sexuality and Hiv Education: A Comprehensive Review of Evaluation Studies. Int. Perspect. Sex Reprod. Health 2015, 41, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketting, E.; Friele, M.; Michielsen, K. Evaluation of Holistic Sexuality Education: A European Expert Group Consensus Agreement. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2016, 21, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauyoumdjian, C.; Guzman, B.L. Sex Education Justice: A Call for Comprehensive Sex Education and the Inclusion of Latino Early Adolescent Boys. Assoc. Mex.-Am. Educ. (AMAE) J. 2013, 7, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, D. Emerging Answers 2007, Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases; National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; ISBN 1586710702. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Stanton, B.; Deveaux, L.; Poitier, M.; Lunn, S.; Koci, V.; Adderley, R.; Kaljee, L.; Marshall, S.; Li, X.; et al. Factors Influencing Implementation Dose and Fidelity Thereof and Related Student Outcomes of an Evidence-Based National HIV Prevention Program. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; McCarraher, D.R.; Phillips, S.J.; Williamson, N.E.; Hainsworth, G. Contraception for Adolescents in Low and Middle Income Countries: Needs, Barriers, and Access. Reprod. Health 2014, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, D. Comprehensive Sex Education for Teens Is More Effective than Abstinence. Am. J. Nurs. 2012, 112, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, E.S.; Lieberman, L.D. Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 68, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantine, N.A.; Jerman, P.; Berglas, N.F.; Angulo-Olaiz, F.; Chou, C.-P.; Rohrbach, L.A. Short-Term Effects of a Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum for High-School Students: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Proulx, C.N.; Coulter, R.W.S.; Egan, J.E.; Matthews, D.D.; Mair, C. Associations of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning–Inclusive Sex Education with Mental Health Outcomes and School-Based Victimization in U. S. High School Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN1 0022-3263. ISBN2 1520-6904. [Google Scholar]

- Haberland, N.; Rogow, D. Sexuality Education: Emerging Trends in Evidence and Practice. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S15–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, M.; Simelane, S.; Fortuny Fillo, G.; Chalasani, S.; Weny, K.; Salazar Canelos, P.; Jenkins, L.; Moller, A.-B.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Say, L.; et al. The State of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.A.; Hirsch, J.S. Pleasure, Power, and Inequality: Incorporating Sexuality into Research on Contraceptive Use. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, A.K.-J.; Montero Vega, A.R.; Sagbakken, M. From Disease to Desire, Pleasure to the Pill: A Qualitative Study of Adolescent Learning about Sexual Health and Sexuality in Chile. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guerrero, N.; Pérez, M. On What Theoretical and Methodological Precepts Should Thestudy and Comprehensive Education on Sexuality for Adolescents and Youth Be Based? Sexol. Y Soc. 2013, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Sales, J.M.; Milhausen, R.R.; DiClemente, R.J. A Decade in Review: Building on the Experiences of Past Adolescent STI/HIV Interventions to Optimise Future Prevention Efforts. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2006, 82, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guse, K.; Levine, D.; Martins, S.; Lira, A.; Gaarde, J.; Westmorland, W.; Gilliam, M. Interventions Using New Digital Media to Improve Adolescent Sexual Health: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. Denying the Sexual Subject: Schools’ Regulation of Student Sexuality. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, L.K.B.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Fernandez, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, J.P.; Frampton, G.K.; Harris, P. Interventions for Encouraging Sexual Behaviours Intended to Prevent Cervical Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, CD001035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballonoff Suleiman, A.; Brindis, C.D. Adolescent School-Based Sex Education: Using Developmental Neuroscience to Guide New Directions for Policy and Practice. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2014, 11, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huebner, D.M.; Perry, N.S. Do Behavioral Scientists Really Understand HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behavior? A Systematic Review of Longitudinal and Experimental Studies Predicting Sexual Behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abt Associates. Safer Sex Intervention: Interim Impact Report, Teen Pregnancy Prevention Replication Study; Report prepared for the Office of Adolescent Health and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Adeomi, A.A.; Adeoye, O.A.; Asekun-Olarinmoye, E.O.; Abodunrin, O.L.; Olugbenga-Bello, A.I.; Sabageh, A.O. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Peer Education in Improving HIV Knowledge, Attitude, and Sexual Behaviours among In-School Adolescents in Osun State, Nigeria. AIDS Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 131756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsford, R.; Bragg, S.; Allen, E.; Tilouche, N.; Meiksin, R.; Emmerson, L.; van Dyck, L.; Opondo, C.; Morris, S.; Sturgess, J.; et al. A School-Based Social-Marketing Intervention to Promote Sexual Health in English Secondary Schools: The Positive Choices Pilot Cluster RCT. Public Health Res. 2021, 9, 1–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, C.; Eads, M.; Barker, G. Engaging Boys and Young Men in the Prevention of Sexual Violence: A Systematic and Global Review of Evaluated Interventions; Sexual Violence Research Initiative and Promundo: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Timpe, Z.; Suarez, N.A.; Phillips, E.; Kaczkowski, W.; Cooper, A.C.; Dittus, P.J.; Robin, L.; Barrios, L.C.; Ethier, K.A. Dosage in Implementation of an Effective School-Based Health Program Impacts Youth Health Risk Behaviors and Experiences. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Valles, J.; Kuhns, L.M.; Manjarrez, D. “Tal Como Somos/Just as We Are”: An Educational Film to Reduce Stigma toward Gay and Bisexual Men, Transgender Individuals, and Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schutte, L.; Meertens, R.M.; Mevissen, F.E.F.; Schaalma, H.; Meijer, S.; Kok, G. Long Live Love. The Implementation of a School-Based Sex-Education Program in the Netherlands. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knowles, V.; Kaljee, L.; Deveaux, L.; Lunn, S.; Rolle, G.; Stanton, B. National Implementation of an Evidence-Based HIV Prevention and Reproductive Health Program for Bahamian Youth. Int. Electron. J. Health Educ. 2012, 15, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezón, C.; Vigil, P.; Rojas, I.; Leiva, M.E.; Riquelme, R.; Aranda, W.; García, C. Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention: An Abstinence-Centered Randomized Controlled Intervention in a Chilean Public High School. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 36, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.W.; Jo, M.; Smith, A.D.; Marshall, B.D.; Thigpen, S.; Offiong, A.; Geffen, S.R. Supplementing Substance Use Prevention with Sexual Health Education: A Partner-Informed Approach to Intervention Development. Health Promot. Pract. 2022, 23, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsey, M.; Layzer, J. Implementing Three Evidence-Based Program Models: Early Lessons from the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Replication Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, S45–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sales, J.M.; Brown, J.L.; DiClemente, R.J.; Rose, E. Exploring Factors Associated with Nonchange in Condom Use Behavior Following Participation in an STI/HIV Prevention Intervention for African-American Adolescent Females. AIDS Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 231417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Montgomery, P.; Knerr, W. Review of the Evidence on Sexuality Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, E.M.D.C.; Ramos, S.C.D.S.; Martins, N.D.S.; Nascimento, M.C.D.; Calheiros, A.P.; Calheiros, C.A.P. Sexuality and Sexually Transmitted Infections: Analysis of Health Student Training/Sexualidade e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis: Análise Da Formação de Alunos Da Área Da Saúde. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. É Fundam. Online 2021, 13, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinga, M. Sexuality Education for Prevention of Pregnancy and HIV Infections: How Do Tanzanian Primary Teachers Deliver It? Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. 2016, 26, 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Osuji, G.E.; Suleh, E.O. Curriculum and Sustainable Learning: Vade Mecum for Teacher Education; CUEA Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neto de Menezes, M.L.; Figueiroa, M.D.N.; Neto, W.B.; de Oliveira Júnior, G.P.; Lourenço, B.L.G.; Falcão, T.C.X.S.A.; Barbosa, B.A. Sex Education from the Perspective of Adolescent Students, Teachers, and Managers of Elementary School in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Int. Arch. Med. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganuza, E.; Olivari, L.; Paño, P.; Buitrago, L.; Lorenzana, C. La Democracia En Acción: Una Visión Desde Las Metodologías Participativas; Antígona Procesos Participativos: Córdoba, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haberland, N.; Rogow, D. Un Sólo Currículo: Pautas Para Un Enfoque Integrado Hacia La Educación En Sexualidad, Género, VIH y Derechoshumanos; The Population Council, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L.M.; Bernholc, A.; Chen, M.; Tolley, E.E. School-Based Interventions for Improving Contraceptive Use in Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD012249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.S.; Abraham, C.; Denford, S.; Mathews, C. Design, Implementation and Evaluation of School-Based Sexual Health Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Qualitative Study of Researchers’ Perspectives. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, E.S.; Constantine, N.A. Sexuality Education. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Brown, B.B., Prinstein, M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1427–1433. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association Sexuality Education as Part of a Comprehensive Health Education Program in K to 12 Schools; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- SIECUS. Support Federal Adolescent Sexual Health Education & Promotion Programs; Sexuality Information Education and Education Council of the United States: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, J.; Aitken, L.; Webb, R.; MacLaren, J.; Salmon, D. Characteristics of Successful Interventions to Reduce Turnover and Increase Retention of Early Career Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 91, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murimi, M.W.; Moyeda-Carabaza, A.F.; Nguyen, B.; Saha, S.; Amin, R.; Njike, V. Factors That Contribute to Effective Nutrition Education Interventions in Children: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 553–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.D.; Hassen, N.; Craig-Neil, A. Employment Interventions in Health Settings: A Systematic Review and Synthesis. Ann. Fam. Med. 2018, 16, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, S.; Farmer, A.; Apps Eccles, K.; McCargar, L. Healthy Strategies for Successful Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance: A Systematic Review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lameiras-Fernández, M.; Martínez-Román, R.; Carrera-Fernández, M.V.; Rodríguez-Castro, Y. Sex Education in the Spotlight: What Is Working? Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.E.; Braren, S.H.; Rincón-Cortés, M.; Brandes-Aitken, A.N.; Chopra, D.; Opendak, M.; Alberini, C.M.; Sullivan, R.M.; Blair, C. Enhancing Executive Functions Through Social Interactions: Causal Evidence Using a Cross-Species Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gardner, P. The Role of Social Engagement and Identity in Community Mobility among Older Adults Aging in Place. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.R.; Ni, L.; Bay, A.A.; Hart, A.R.; Perkins, M.M.; Hackney, M.E. Psychosocial Effects of Remote Reading with Telephone Support versus In-Person Health Education for Diverse, Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.M.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the Quality of Reports of Randomized Clinical Trials: Is Blinding Necessary? Control Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.; Valentine, J. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cascaes da Silva, F.; Valdivia Arancibia, B.; da Rosa Iop, R.; Barbosa Gutierres Filho, P.; da Silva, R. Escalas y Listas de Evaluación de La Calidad de Estudios Científicos. Rev. Cuba. Inf. Cienc. Salud 2013, 24, 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Jerlström, C.; Adolfsson, A. Prevention of Chlamydia Infections with Theater in School Sex Education. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020, 36, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, N.; Matshaba, M.; Gabaitiri, L.; Anabwani, G. Revealing a Safer Sex Option to Reduce HIV Risk: A Cluster-Randomized Trial in Botswana. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubu, I.; Garmaroudi, G.; Sadeghi, R.; Tol, A.; Yekaninejad, M.S.; Yidana, A. Assessing the Impact of an Educational Intervention Program on Sexual Abstinence Based on the Health Belief Model amongst Adolescent Girls in Northern Ghana, a Cluster Randomised Control Trial. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goesling, B.; Scott, M.E.; Cook, E. Impacts of an Enhanced Family Health and Sexuality Module of the HealthTeacher Middle School Curriculum: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, S125–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangi, A.; Dolcini, M.M.; Harper, G.W.; Boyer, C.B.; Pollack, L.M. The Adolescent Medicine Trials Netw Psychosocial Outcomes of Sexual Risk Reduction in a Brief Intervention for Urban African American Female Adolescents. J. HIV AIDS Soc. Serv. 2013, 12, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbee, A.P.; Cunningham, M.R.; van Zyl, M.A.; Antle, B.F.; Langley, C.N. Impact of Two Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Interventions on Risky Sexual Behavior: A Three-Arm Cluster Randomized Control Trial. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, S85–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, L.J.; Watnick, D.; Silver, E.J.; Rivera, A.; Sclafane, J.H.; Rodgers, C.R.R.; Leu, C.-S. Reducing HIV/STI Risk Among Adolescents Aged 12 to 14 Years: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Project Prepared. Prev. Sci. 2021, 22, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrbach, L.A.; Berglas, N.F.; Jerman, P.; Angulo-Olaiz, F.; Chou, C.-P.; Constantine, N.A. A Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum for Adolescents: 1-Year Outcomes from a Cluster-Randomized Trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, K.; Anderson, P.; Laris, B.A.; Barrett, M.; Unti, T.; Baumler, E. A Group Randomized Trial Evaluating High School FLASH, a Comprehensive Sexual Health Curriculum. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, C.; Eggers, S.M.; Townsend, L.; Aarø, L.E.; de Vries, P.J.; Mason-Jones, A.J.; de Koker, P.; McClinton Appollis, T.; Mtshizana, Y.; Koech, J.; et al. Effects of PREPARE, a Multi-Component, School-Based HIV and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Prevention Programme on Adolescent Sexual Risk Behaviour and IPV: Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 1821–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mmbaga, E.J.; Kajula, L.; Aarø, L.E.; Kilonzo, M.; Wubs, A.G.; Eggers, S.M.; de Vries, H.; Kaaya, S. Effect of the PREPARE Intervention on Sexual Initiation and Condom Use among Adolescents Aged 12–14: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reyna, V.F.; Mills, B.A. Theoretically Motivated Interventions for Reducing Sexual Risk Taking in Adolescence: A Randomized Controlled Experiment Applying Fuzzy-Trace Theory. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 1627–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jemmott, J.B.; Jemmott, L.S.; O’Leary, A.; Ngwane, Z.; Lewis, D.A.; Bellamy, S.L.; Icard, L.D.; Carty, C.; Heeren, G.A.; Tyler, J.C.; et al. HIV/STI Risk-Reduction Intervention Efficacy with South African Adolescents over 54 Months. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walsh-Buhi, E.R.; Marhefka, S.L.; Wang, W.; Debate, R.; Perrin, K.; Singleton, A.; Noble, C.A.; Rahman, S.; Maness, S.B.; Mahony, H.; et al. The Impact of the Teen Outreach Program on Sexual Intentions and Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Jinabhai, C.; Dlamini, S.; Sathiparsad, R.; Eggers, M.S.; de Vries, H. Effects of a Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Program in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, J.P.; Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Ballester, R.; Huedo-Medina, T.B. Effectiveness of a School HIV/AIDS Prevention Program for Spanish Adolescents. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2012, 24, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Espada, J.P.; Morales, A.; Orgilés, M.; Jemmott, J.B.; Jemmott, L.S. Short-Term Evaluation of a Skill-Development Sexual Education Program for Spanish Adolescents Compared with a Well-Established Program. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, J.P.; Escribano, S.; Morales, A.; Orgilés, M. Two-Year Follow-Up of a Sexual Health Promotion Program for Spanish Adolescents. Eval. Health Prof. 2017, 40, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.; Espada, J.P.; Orgilés, M. A 1-Year Follow-up Evaluation of a Sexual-Health Education Program for Spanish Adolescents Compared with a Well-Established Program. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: Morristown, NJ, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social Influence; Thomson Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, J.A.; Pfau, M. Inoculation Theory of Resistance to Influence at Maturity: Recent Progress in Theory Development and Application and Suggestions for Future Research. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2005, 29, 97–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfeddali, I.; Bolman, C.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; Wiers, R.W.; de Vries, H. The Role of Self-Efficacy, Recovery Self-Efficacy, and Preparatory Planning in Predicting Short-Term Smoking Relapse. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C.D. The Altruism Question: Toward a Social-Psychological Answer; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht, B. A Short Organum for the Theatre. In Brecht on Theatre: The Development of Aesthetic; Willett, J., Ed.; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1864; pp. 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Catania, J.A.; Kegeles, S.M.; Coates, T.J. Towards an Understanding of Risk Behavior: An AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM). Health Educ. Q. 1990, 17, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantin, H.; Schwartz, S.J.; Sullivan, S.; Prado, G.; Szapocznik, J. Ecodevelopmental HIV Prevention Programs for Hispanic Adolescents. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2004, 74, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perrino, T.; González-Soldevilla, A.; Pantin, H.; Szapocznik, J. The Role of Families in Adolescent HIV Prevention: A Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 3, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R. Intimate Partner Violence: Causes and Prevention. Lancet 2002, 359, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.D.; Fisher, W.A. Changing AIDS-Risk Behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, V.F. A Theory of Medical Decision Making and Health: Fuzzy Trace Theory. Med. Decis. Mak. 2008, 28, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michielsen, K.; de Meyer, S.; Ivanova, O.; Anderson, R.; Decat, P.; Herbiet, C.; Kabiru, C.W.; Ketting, E.; Lees, J.; Moreau, C.; et al. Reorienting Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Research: Reflections from an International Conference. Reprod. Health 2015, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barriuso-Ortega, S.; Heras-Sevilla, D.; Fernández-Hawrylak, M. Análisis de Programas de Educación Sexual Para Adolescentes En España y Otros Países. Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2022, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanipour, H.; Yaghmaeeyan, H.; Chizari, H.; Hossaini, S. Sex Education Programs for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. erj 2021, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, Z.; Shamsi, M.; Roozbahani, N.; Moradzadeh, R. The Effect of Educational Intervention Program on Promoting Preventive Behaviors of Urinary Tract Infection in Girls: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. Health Psychology; McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buhi, E.R.; Goodson, P. Predictors of Adolescent Sexual Behavior and Intention: A Theory-Guided Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson, M.; Covey, J.; Rosenthal, H.E.S. Theory of Planned Behavior Interventions for Reducing Heterosexual Risk Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 1454–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Darabi, F.; Kaveh, M.; Khalajabadi Farahani, F.; Yaseri, M.; Majlessi, F.; Shojaeizadeh, D. The Effect of a Theory of Planned Behavior-Based Educational Intervention on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Iranian Adolescent Girls: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Res. Health Sci. 2017, 17, e00400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kok, G.; Schaalma, H.; de Vries, H.; Parcel, G.; Paulussen, T. Social Psychology and Health Education. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 7, 241–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen, D.; Yaksich, J.D.; Aebersold, M.; Villarruel, A. Fidelity After SECOND LIFE Facilitator Training in a Sexual Risk Behavior Intervention. Simul. Gaming 2016, 47, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbee, A.P.; Antle, B.; Langley, C.; Cunningham, M.R.; Whiteside, D.; Sar, B.K.; Archuleta, A.; Karam, E.; Borders, K. How to Ensure Fidelity in Implementing an Evidence Based Teen Pregnancy Prevention Curriculum. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, C.; Ellis, R.P.; Eyssel, F.; Zou, J.; Schiebinger, L. Sex and Gender Analysis Improves Science and Engineering. Nature 2019, 575, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sugimoto, C.R.; Ahn, Y.-Y.; Smith, E.; Macaluso, B.; Larivière, V. Factors Affecting Sex-Related Reporting in Medical Research: A Cross-Disciplinary Bibliometric Analysis. Lancet 2019, 393, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, M.W.; Stefanick, M.L.; Peragine, D.; Neilands, T.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pilote, L.; Prochaska, J.J.; Cullen, M.R.; Einstein, G.; Klinge, I.; et al. Gender-Related Variables for Health Research. Biol. Sex Differ. 2021, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, C.G.; Saperstein, A.; Magliozzi, D.; Westbrook, L. Gender and Health: Beyond Binary Categorical Measurement. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2019, 60, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky-Higgins, K.; Miclau, T.A.; Mackechnie, M.C.; Aguilar, D.; Avila, J.R.; dos Reis, F.B.; Balmaseda, R.; Barquet, A.; Ceballos, A.; Contreras, F.; et al. Barriers to Clinical Research in Latin America. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, M.R.; Cornish, F.; Zimmerman, R.S.; Johnson, B.T. Health Behavior Change Models for HIV Prevention and AIDS Care. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 66, S250–S258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Main Terms | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Sexuality | “sexuality” OR “sex” OR “HIV” OR “pregnancy” OR “STD” OR “abstinence” OR “reproductive” OR “sexually transmitted infection” OR “sexually transmitted disease” OR “STI” OR “AIDS” OR “reproductive health” OR ”condom” OR “contracept” OR “protected sex” OR “unprotected sex” OR ”abstinence” OR “safe sex” |

| Education | “education” OR “intervention” OR “program” OR “prevention” OR “treatment” OR “promotion” |

| Adolescent | “adolescent” OR “teenager” OR “teen” OR “juvenile” OR “youth” OR “young” OR “high school students” OR “middle school students” OR “girls” OR “boys” |

| Randomized control trial | “randomized control trial” OR “RCT” OR “randomized trial” OR “randomized clinical trial” OR “randomized controlled trial” |

| Intervention | Study | Jadad Scale Score | Sample Age (Years) | Setting | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “SAFETY” intervention | Jerlström et al., 2020 [91] | 3 | 15 | Educational | Sweden |

| Not specified | Angrist et al., 2019 [92] | 3 | 12–14 | Educational | Botswana (Kgatleng, Kweneng, South East, and Southern) |

| Comprehensive sexuality educational program | Yakubu et al., 2019 [93] | 3 | 14–19 | Educational | Ghana (Tamale Metropolis) |

| “Health Teacher” Family Health and Sexuality module | Goesling et al., 2016 [94] | 3 | 12 | Educational | United States (Chicago) |

| Project ÒRÉ | Bangi et al., 2013 [95] | 3 | 14–18 | Community-based | United States (San Francisco) |

| Reducing the Risk (RTR) | Barbee et al., 2016 [96] | 5 | 14–19 years | Community-based | United States (Louisville, Kentucky) |

| Love Notes (LN) | 14–19 years | Community-based | United States (Louisville, Kentucky) | ||

| Project PREPARED | Bauman et al., 2021 [97] | 3 | 12–15 years | Clinical | United States (Bronx, New York) |

| High School FLASH 1 1 | Rohrbach et al., 2015 [98] Constantine et al., 2015 [39] | 3 | 12–18 years | Educational | United States (Los Angeles) |

| High School FLASH 2 1 | Coyle et al., 2021 [99] | 3 | 15 years | Educational | United States (Los Ángeles) |

| PREPARE 1 2 | Mathews et al., 2016 [100] | 3 | 13 years (mean age) | Educational | South Africa (Western Cape) |

| PREPARE 2 2 | Mmbaga et al., 2017 [101] | 3 | 12–14 years Tanzania | Educational | Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) |

| RTR + | Reyna and Mills, 2014 [102] | 3 | 16 years (mean age) | Educational | United States (Arizona, Texas, and New York) |

| The HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention | Jemmott et al., 2016 [103] | 3 | 12–18 years | Educational | South Africa (Eastern Cape Province) |

| Teen Outreach Program (TOP) | Walsh-Buhi et al., 2016 [104] | 3 | 14–16 years | Educational | United States (Florida) |

| Comprehensive sexuality education intervention | Kemigisha et al., 2019 [26] | 3 | 11–15 years | Educational | Uganda (Mbarara district) |

| Teenage Pregnancy PreventionProgram | Taylor et al., 2014 [105] | 3 | Males mean age: 14.6 years Females mean age: 13.9 years | Educational | South Africa (KwaZulu-Natal) |

| COMPAS (Competencias para adolescentes con una sexualidad saludable-Skills for Adolescents with a Healthy Sexuality) | Espada et al., 2012, 2015, 2017 [106,107,108]; Morales et al., 2015 [109] | 3 | 15–18 years | Educational | Spain |

| Intervention | Number of Sessions and Frequency | Length of Session | Total Hours | Facilitators | Approach | Intervention Methodology | Type of Intervention | Facilitators Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “SAFETY” intervention | One | 80 min. | 80 min. | Professional actors, staff from the municipality’s youth guidance center, and the school nurse | Risk-oriented | Participatory | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| Not specified [92] | Two | 60 min. | 60 min. | Youth facilitators | Risk-oriented | Participatory Video | Mixed-sex groups | 5 days’ training |

| Comprehensive sexuality educational program | Six (two sessions weekly) | NI | NI | Qualified midwives | Comprehensive | Participatory | Mixed-sex groups | NI |

| “Health Teacher” Family Health and Sexuality module | Nine (the sessions were conducted for between two weeks and four months) | 45–90 min. | 10.1 h. (on average) | School teachers | Comprehensive | Participatory Video | Mixed-sex groups | 3 days’ training |

| Project ÒRÉ | One | 5 h. | 5 h. | African American female health educators at community-basedorganizations | Comprehensive | Discussion Video | African American female adolescents | Facilitators received training |

| Reducing the Risk (RTR) | 16 (weekly: the sessions were conducted on two days (two Saturdays)) | Total hours distributed in two consecutive Saturdays | 13 h. | Trained facilitators | Comprehensive | Participatory video | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| Love Notes (LN) | 13 (weekly) | 13 h. | Trained facilitators | Comprehensive | Participatory video | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training | |

| Project PREPARED | 14 (weekly) | 2 ¼ hours | 35 h. | Trained facilitators | Comprehensive | Participatory | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| High School FLASH 1 | 12 (sessions were implemented across an average span of 53 days) | 50 min. | 10 h. | Planned Parenthood Los Angeles staff | Comprehensive | Participatory | Mixed-sex groups | 2 days’ training |

| High School FLASH 2 | 15 (daily and alternate days) | 50 min. 70–90 min. | 12.9 h. (on average) | Sexuality educators from existing reproductive health and education organizations | Comprehensive | Participatory | Mixed-sex groups | 2 days’ training |

| PREPARE 1 | 21 (weekly) | 1–1.5 h | 26.3 (on average) | Trained facilitators | Comprehensive | Participatory | Mixed-sex groups | 2-week training course |

| PREPARE 2 | 25 (weekly) | 40–80 min. 60–90 min. | 19 h. | Teachers, peer educators, and healthcare providers | Comprehensive | Participatory–interactive | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| RTR + | 15 (on average, a full intervention was implemented within 15.2 days) | 2 h | 16 h. | Research assistants | Abstinence-plus | Participatory–interactive | Mixed-sex groups | Over 16 h of training |

| The HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention | Six (daily) | 1 h | 12 h. | Women and men bilingual in English and Xhosa | Risk-oriented | Participatory–interactive | Mixed-sex groups | 8 days’ training |

| Teen Outreach Program (TOP) | 25 (weekly) | NI | NI | Trained teachers | Comprehensive | Participatory–interactive | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| Comprehensive sexuality education intervention | 11 (montly) | 1–2 h | 16.5 h. (in avergae) | Volunteer university students | Comprehensive | Participatory–interactive | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Program | 12 (weekly) | 1 h | 24 (on average) | Trained facilitators | Comprehensive | Participatory–interactive video | Mixed-sex groups | Facilitators received training |

| COMPAS (Competencias para adolescentes con una sexualidad saludable-Skills for Adolescents with a Healthy Sexuality) | Five (weekly) | 1 h | 5 h. | Trained psychologists | Risk-oriented | Participatory–interactive | Mixed-sex groups | 6 h training |

| Theory | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Theory Of Planned Behavior [110] | Theory Of Reasoned Action [111,112] | Social Cognitive/ Learning Theory [113,114] | The Social Ecological Model [115] | Social Influence Theory [116] | Social Inoculation Theory [117] | Cognitive-Behavioral Theory | I-Change Model [118] | Empathy Model of Altruism [119] | Brecht’s Theory [120] | Health Belief Model | AIDS Risk Reduction Model [121] | Ecodevelopmental Theory [122,123] | Jewkes Conceptual Framework [124] | The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model [125] | Fuzzy-Trace Theory [126] | Positive Youth Development |

| High School FLASH 1 | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| High School FLASH 2 | x | ||||||||||||||||

| “SAFETY” intervention | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Not specified [92] | NI | ||||||||||||||||

| Comprehensive sexuality educational program | x | ||||||||||||||||

| “Health Teacher” Family Health and Sexuality module | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Project ÒRÉ | x | ||||||||||||||||

| RTR (Reducing the Risk) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Love Notes (LN) | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Project PREPARED | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| PREPARE programme 1 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| PREPARE programme 2 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| RTR + | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| The HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Teen Outreach Program (TOP) | x | ||||||||||||||||

| SRH intervention | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| TP Program | x | ||||||||||||||||

| COMPAS | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Name of the Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| “SAFETY” intervention |

|

| Not specified [92] |

|

| Comprehensive sexuality educational program |

|

| “Health Teacher” Family Health and Sexuality module |

|

| Project ÒRÉ |

|

| RTR (Reducing the Risk) |

|

| Love Notes (LN) |

|

| Project PREPARED |

|

| High School FLASH 1 |

|

| High School FLASH 2 |

|

| PREPARE 1 |

|

| PREPARE 2 |

|

| RTR + |

|

| The HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention |

|

| Teen Outreach Program (TOP) |

|

| SRH intervention |

|

| Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Program |

|

| COMPAS (Competencias para adolescentes con una sexualidad saludable-Skills for Adolescents with a Healthy Sexuality) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Cortés, B.; Leiva, L.; Canenguez, K.; Olhaberry, M.; Méndez, E. Shared Components of Worldwide Successful Sexuality Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054170

Torres-Cortés B, Leiva L, Canenguez K, Olhaberry M, Méndez E. Shared Components of Worldwide Successful Sexuality Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054170

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Cortés, Betzabé, Loreto Leiva, Katia Canenguez, Marcia Olhaberry, and Emmanuel Méndez. 2023. "Shared Components of Worldwide Successful Sexuality Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054170

APA StyleTorres-Cortés, B., Leiva, L., Canenguez, K., Olhaberry, M., & Méndez, E. (2023). Shared Components of Worldwide Successful Sexuality Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054170